New Mars Forums

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

Announcement

#1 2025-10-28 23:05:18

- Oldfart1939

- Member

- Registered: 2016-11-26

- Posts: 2,490

Starship Lunar Lander and landing legs

We've had some conversation on this forum about landing methods for the lunar lander.

Here's a fairly interesting YouTube discussion about landings and how to carry it out.

Offline

Like button can go here

#2 2025-10-29 06:02:22

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 24,075

Re: Starship Lunar Lander and landing legs

This post is reserved for an index to posts that may be contributed by NewMars members:

Index:

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#3 2025-10-29 10:36:28

- GW Johnson

- Member

- From: McGregor, Texas USA

- Registered: 2011-12-04

- Posts: 6,146

- Website

Re: Starship Lunar Lander and landing legs

I saw the videos, plural. The first one takes on their rough field landing system. The second takes on refueling in space, and cut off before it was finished.

It appears that if you decide to land tall things, you need a discerning pilot to target the right spot amongst all the hazards, and who can adapt the positioning of landing surfaces to the unevenness just before the touchdown. That has to happen faster than humans can act. This is going to be based on AI, apparently.

Tip-over after touchdown on rough surfaces with tall, narrow objects is a real thing, and some recent commercial landers have demonstrated that ugly little fact of life. Any horizontal speed at touchdown can tump you right over in a split second, even in low lunar gravity. That was the proximate cause of the Japanese failure, and at least one of the two US failures. Both designs were tall and narrow, presuming the controls were good enough to adapt.

Given the track record of failures and crashes because of events unanticipated by the programmers with Tesla self-driving software, I would hesitate to take the same approach with a crewed device as the Japanese and that one American commercial lander company. The other American commercial lander was more squat and more successful.

Controls can only be so good, not perfect. And the moon is infamous for having unevenness and randomly scattered but dense distributions of obstacles and hazards.

But my fears may or may not be justified. I just do not trust AI, because I see lots of errors and falsehoods out of the ones available to the public. I still think the term AI is an oxymoron: there is NO intelligence or understanding of anything there, there is only imitation of style plus very high speed. Computers process bad data as well as good data. It all looks the same when it comes out of them.

GW

Last edited by GW Johnson (2025-10-29 10:39:30)

GW Johnson

McGregor, Texas

"There is nothing as expensive as a dead crew, especially one dead from a bad management decision"

Offline

Like button can go here

#4 2025-10-29 11:02:23

- Void

- Member

- Registered: 2011-12-29

- Posts: 9,286

Re: Starship Lunar Lander and landing legs

I try not to interfere with professional conversations, but I see some things.

For rough landings, the special landing engines may be able to counteract a toppling tendency. They are not too powerful though.

I keep seeing reports that the Lunar lander engines will be retractable. I cannot understand why they would do that.

I also suggest that some cargo could be attached directly to the landing legs to make the ship less top heavy, and to make cargo accessible without the elevator.

It is my opinion also that landing legs could be left behind on the Lunar surface like the lower stage of the LEM was left behind. This would reduce propellant consumption.

Legs, in my opinion should be made of materials desired on the Moon that cannot be gotten easily from the Moon. They also should be constructed to accommodate cargo containers.

Just my "Two-Nickles". (Inflation).

Ending Pending ![]()

Last edited by Void (2025-10-29 11:07:17)

Is it possible that the root of political science claims is to produce white collar jobs for people who paid for an education and do not want a real job?

Online

Like button can go here

#5 2025-10-29 15:41:53

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 8,499

Re: Starship Lunar Lander and landing legs

ULA's "crasher stage" horizontal lander used thrusters mounted to both ends of the tank to land a Centaur-sized propellant tank with far less probability of "tipping over" during the landing. Creating a sufficiently wide landing gear track for a tallboy beer can is much easier to do when the can is laying on its side. Trying to land the propellant can on-end requires very large and heavy landing gear to create a track wide enough to avoid tipping over. Since the moon is 1/6th Earth gravity and some of the propellant will be consumed during descent, far less propulsive power is required from the thrusters, which makes mounting them on either end of the stage less problematic.

Offline

Like button can go here

#6 2025-10-29 15:44:07

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,460

Re: Starship Lunar Lander and landing legs

here is one of many topics.

Much changes when a lunar version does not need to come back to earth.

Six-legged freaks - can the Starship land on those legs?

The legs were also part of our discusions on Landing legs for the BFR

some feel that a starship for the moon is over kill SpaceX should withdraw Starship as an Artemis lunar lander.

Of course the Mars version is also a puzzle with the full sized starship for colonizing feeling that support for the ship requires Starship concrete Mars landing pad

Of course right sizing the ship is another alternative. Forty 40 Ton Mars Delivery Mechanism

Offline

Like button can go here

#7 2026-02-01 14:51:03

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,460

Re: Starship Lunar Lander and landing legs

Lunar Starship was never meant to come home to Earth, SpaceX admits

SpaceX’s lunar Starship was never designed to blaze back through Earth’s atmosphere in a shower of plasma. Instead, the company has quietly positioned its Human Landing System as a one‑way ferry that lives and dies in cislunar space, while NASA’s Orion capsule handles the brutal trip home. That architectural choice, long embedded in Artemis planning documents, is only now breaking through to a wider public that assumed every Starship would eventually come back to Earth.

Framed correctly, this is less a retreat from reusability than a bet on specialization. By stripping out the heavy heat shield and recovery hardware, SpaceX can turn its lunar variant into a tall, fuel‑hungry elevator between orbit and the Moon, while the rest of the Artemis stack focuses on launch and reentry. The tradeoffs behind that decision reveal how NASA and SpaceX are trying to thread the needle between ambition, schedule pressure, and basic physics.

Artemis needs a lunar shuttle, not a return capsule

NASA’s Artemis architecture was built around the idea that no single vehicle would do everything, and that includes the trip home. The agency’s own outline for Artemis III makes clear that astronauts will launch on the Space Launch System, ride in Orion to lunar orbit, then transfer into a separate lander for the descent and ascent. The Artemis program description spells out that SLS and Orion are the pieces designed for deep‑space transit and Earth reentry, while the lander is a dedicated vehicle for the last leg between orbit and the Moon’s surface.That division of labor is why NASA refers to SpaceX’s vehicle as the Starship Human Landing System, or HLS, rather than simply Starship. Agency material on the Initial Human Landing concepts shows a tall, stripped‑down lander on the Moon, with Orion waiting in lunar orbit as the ride home. In other words, the mission design assumes from the start that the lunar Starship is a shuttle between the Moon and orbit, not a capsule that ever sees Earth’s atmosphere.

Inside the one‑way Starship design

SpaceX’s own technical descriptions underline that the lunar lander is a specialized branch of the broader Starship family. A detailed overview of Starship‑HLS notes that the Human Landing System is derived from Starship but modified for operation as a lunar lander, and explicitly states that this configuration is not designed to return to Earth. That is not a late‑breaking compromise, it is a core assumption baked into the hardware, from the missing heat shield to the absence of aerodynamic control surfaces needed for atmospheric entry.The logic behind that choice has even filtered into public discussion among enthusiasts and engineers. In one widely shared explanation, Forrest and Townsend tell fellow fans that engineers “dont’ plan on ont he lunar starship to return to earth, no heatshield, save on the cerami,” while David Cluett promises to explain the trade in layman’s terms. The point is simple: every kilogram not spent on ceramic tiles and reentry systems can be spent on propellant, cargo, or life support for the lunar mission itself.

Why Orion still matters in a Starship era

The decision to keep the lunar Starship in space also explains why Orion remains central to NASA’s plans, despite Starship’s headline‑grabbing capabilities. A technical discussion of whether the lander could replace Orion, framed as Can Starship Lunar return to Earth orbit so Orion is not needed anymore, points back to the reality that Orion on SLS is planned to handle the high‑energy return and splashdown. The Orion capsule is built around a robust heat shield and abort systems that the lunar Starship variant simply does not carry.Programmatically, that means Artemis is locked into a choreography where SLS, Orion, and the lander are all indispensable. The SLS missions listed for Artemis I, Artemis II, and beyond show a steady cadence of Orion flights, while separate documentation describes how the Starship Human Landing will be instrumental in ferrying crews from lunar orbit to the surface and back. That is why, even in a Starship era, Orion’s role as the Earth‑return vehicle is not a redundancy but a structural pillar of the mission design.

A “simplified” mission profile, still complex in practice

As schedule pressure mounts, SpaceX has been working with NASA on what it calls a simplified mission architecture for the lunar lander, but that streamlining does not include bringing the vehicle home. Company representatives have described to NASA a Starship for NASA approach that reduces the number of on‑orbit refueling events and mission steps while still delivering astronauts to the lunar surface. A separate account of that simplified approach notes that the company is defending the viability of its lander even as it trims complexity to hit key milestones.Critics inside the space community have questioned whether those changes are enough. At a high‑profile event, former NASA leaders Charlie Bolden and Jim Bridenstine expressed skepticism that the current Starship schedule could deliver on time, even with a leaner mission design. Yet SpaceX has publicly stood behind its timeline, with one detailed feature on its lunar plans, titled around Fly Me to the Moon, stressing that, unlike Apollo, Unlike Apollo, Artemis III will rely on a multi‑vehicle choreography that includes several crucial milestones in 2025.

Refueling, timelines, and the politics of delay

Behind the scenes, the biggest technical swing remains in‑space refueling, which is essential if a non‑returning lander is going to haul enough propellant to and from the Moon. SpaceX’s official updates describe how the next major flight milestones tied specifically to HLS will be a long‑duration flight test and an in‑space propellant transfer in Earth orbit. Without those capabilities, the one‑way lunar Starship would struggle to carry the fuel it needs for multiple sorties between lunar orbit and the surface.That technical risk feeds directly into political anxiety. In one public exchange, Rob Jacobs But the points out that the many Falcon 9 flights are irrelevant to NASA’s immediate problem, because what the agency needs is HLS, which is a special version of Starship. That concern has grown loud enough that NASA has signaled it may consider new proposals from other top space companies to get America back to the Moon if delays mount, a reminder that the lunar Starship’s one‑way design does not insulate it from competition.

Offline

Like button can go here

#8 2026-02-10 15:37:00

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,460

Re: Starship Lunar Lander and landing legs

we now have a detour space x going to the moon instead of mars

Offline

Like button can go here

#9 Yesterday 10:11:55

- GW Johnson

- Member

- From: McGregor, Texas USA

- Registered: 2011-12-04

- Posts: 6,146

- Website

Re: Starship Lunar Lander and landing legs

Should not be a surprise. Money talks.

His SpaceX and Tesla baseline incomes come from government contracting. He is being paid to land people on the moon, if he can. He IS NOT being paid by anybody to go to Mars. If he defaults on his moon landing commitments, he will lose far too much credibility to be a major space contractor anymore, to NASA or DOD. That is "default" by not doing what he promised to attempt. "Failure" by not being able to do it, is a different issue.

GW

Last edited by GW Johnson (Yesterday 10:12:58)

GW Johnson

McGregor, Texas

"There is nothing as expensive as a dead crew, especially one dead from a bad management decision"

Offline

Like button can go here

#10 Yesterday 15:30:43

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,460

Re: Starship Lunar Lander and landing legs

I started to go back through starship topic as it suggested methane back in 2018 and found Louis speculated as early as in 2019 "2016 announcement for a 2024 landing." seems that was off.

here is the post about the top heavy version

I just took an approximate look at the Spacex BFS/Starship landing pad area required for rough-field capability on the moon, Mars, and Earth. The only way to achieve this, is with the folding-panel idea mentioned in post 143 above. The required total landing pad surface areas fall in the 30-45 square meter class, not the 2.5 to 3-something sq.m that Spacex currently shows in its illustrations.

Such large pad areas will have to fold out of the way. There is no way around that larger, folding landing pad requirement, if rough field capability on Mars and the moon (not to mention Earth) is desired. Otherwise you are restricted to reinforced concrete (or solid rock) aprons many feet thick.

See the posting "Designing Rough Field Capability Into the Spacex Starship", posted 2-4-19, on my "exrocketman" site. For those who don't know, that site is http://exrocketman.blogspot.com.

What I found is that handling what the bulk of Mars's surface seems to be like, is the critical design condition. What works for that is more-than-good for the moon, and for Earth, despite the variance in surfaces and properties and gravity. It's complicated, surprise, surprise! So what isn't?

GW

Of course a reload of fuel changes the game.

Point 1: Landing is not the worst problem, refilled takeoff is the problem. Takeoff weights, figured at local gravity, are roughly 5 times higher than landing weights. Landing weight times 2 (to cover the dynamics of touchdown) is still the smaller applied bearing pressure, of the two conditions. That being said, 3 landing pads ~ 1 m diameter is too small even just to land safely across the bulk of Mars's surface, and by a factor near 8.

Point 2: large fixed-geometry landing pad surfaces, whether discarded on takeoff or not, will seriously interfere with the entry hypersonic aerodynamics, shedding shock waves that will destroy adjacent structures by shock-impingement heating, not to mention upsetting aerodynamic stability and control.

Point 3: even if you solve the entry aerodynamics and heating problems, you must add heat shields to these landing pad structures to survive entry. By the time you have done that, you have very likely added enough weight to have covered hydraulically-opened and folded landing pad surfaces.

These reusable folding landing pad surfaces would resemble landing gear doors, built into the trailing edges of fins that contact the surface all along their trailing edges, not just at the tips.

I've already been through all the calculations that demonstrate much larger landing pad surfaces (around 45-46 sq.m total) will inevitably be required. These are posted over at my "exrocketman" site. If you go look, that same article shows a sketch of what I am talking about (folding landing pad surfaces). Such surfaces are ~ factor 20 larger in area than anything Spacex has considered so far, if the bulk of Mars's surface will be feasible for landings and takeoffs. Same for the moon.

This folding-pad idea is really very little different from the fold-out landing legs Spacex uses on its Falcon cores, or originally proposed on its earlier versions of the BFS design. Except, that I rearranged the geometry to get very large pad surfaces in an easy-to-build design, which fold to provide no aerodynamics or heating problems, and which require no special heat shielding.

They (Spacex) didn't do that, which suggests to me they have not yet thought their way through the surface safe bearing capability problem.

It's something they will have to face, right here on Earth for off-site emergency landings, as well as landing on unprepared surfaces on the moon and Mars. They obviously have not done that yet.

GW

Offline

Like button can go here

#11 Yesterday 15:35:38

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,460

Re: Starship Lunar Lander and landing legs

We later saw the pogo pin landing gear and went oh no for lunar landing.

but here is the latest version

Offline

Like button can go here

#12 Today 11:04:33

- GW Johnson

- Member

- From: McGregor, Texas USA

- Registered: 2011-12-04

- Posts: 6,146

- Website

Re: Starship Lunar Lander and landing legs

They still have not thought rough-field landings through, because they have never, ever made one! There are few alive today who ever really did. The young crowd today seems blissfully unaware of what it takes to make a rough-field landing on soft ground, with a rocket vehicle making a powered landing. The exception seems to be Firefly. Their design, which worked on the moon, appears to be inspired by what worked decades ago with Surveyor, Apollo, Viking on Mars, etc.

Lunar regolith might be a tad stronger than Martian regolith because the lunar particles are sharp and the Martian ones are not. But the difference is of order factor 2, not orders of magnitude. Both regoliths resemble nothing so much as sand dune sand here on Earth. The presence of scattered rocks within that do not touch provides no reinforcement whatsoever. Earthly sand dune sand is listed in most Earthly foundation design references as having an allowable bearing pressure of 1 to 2 US tons per square foot = 0.1 to 0.2 MPa. The failure pressure is factor 2 to at most 2.5 above that allowable. Those are VERY LOW values to deal with!

When landing, your vehicle is lightweight, unless it is to take off again. Whatever that local-gravity weight is, there are dynamics of touchdown, and off-angle effects leading to one pad touching first. Both require factoring up the static weight by a factor of 2, for a transient landing pressure under the first pad of 4 times what the static value would be. None of those dynamics affect takeoff, the pads see only the static weight, until the vehicle lifts off. But if you are refilling propellant locally, as is often proposed now, that weight is the full max takeoff weight. Which may be some 5 to 7 times the near-empty weight at touchdowndown.

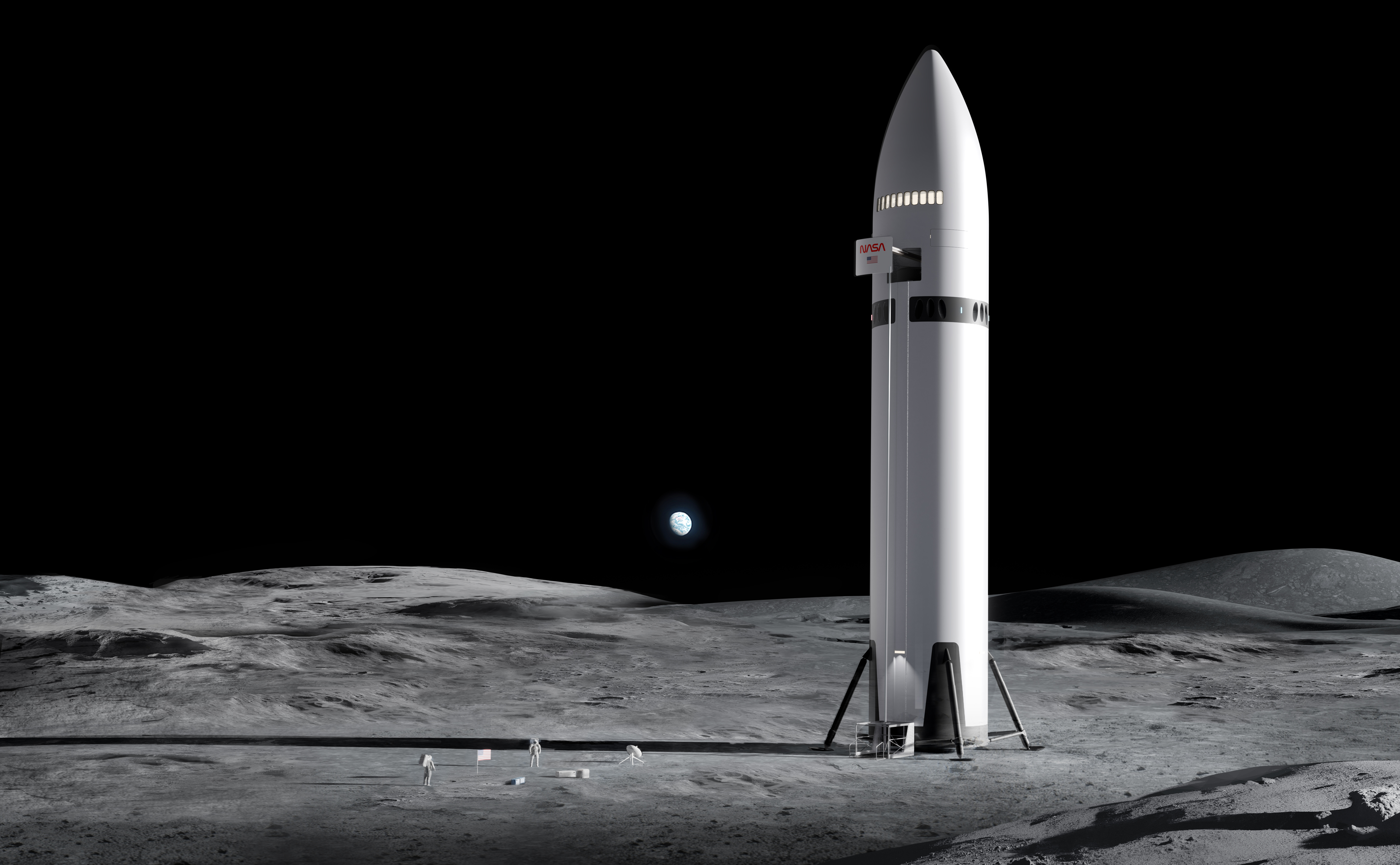

I see nothing in the HLS illustration to show any recognition of those pad bearing pressure issues. I also see nothing in the illustration to suggest any cognizance of the risk of coming down on uneven ground, which is actually depicted nearby, in the illustration, and not as bad as some actually seen during Apollo! The cg is about halfway up the vehicle, with the weight vector hanging from it. If that vector points to a location on the surface outside the polygon defined by the landing pads, the vehicle WILL fall over (and explode)! And that is if there is zero horizontal speed at the moment of touchdown! If there is horizontal speed, the lead pad will dig-in and "trip" the vehicle, even if the weight vector falls well inside the polygon.

I see no cognizance in any of the press release illustration from SpaceX (or anybody else) about these issues and risks. The same ones that twice tripped-up Intuitive Machines on the moon, and the Japanese lander, too.

The criteria to avoid this have been known since the early 1960's. (1) Min dimension of the pad polygon must be greater than the cg height. (2) Make sure the transient bearing pressure under the pads is closer to the allowable bearing pressure than the failure pressure on landing, and similar for the static bearing pressure, for takeoff. (3) Tip the pads on spring mounts inward a little, so that the lead pad won't dig in so easily if you touch down with some horizontal speed. (4) Make sure that you can hover just above the surface, for a significant time, so that whatever is controlling the vehicle during the landing can "see and avoid" uneven high-slope ground, big boulders, and cavities or other holes.

And, also since the early 1960's, if you do not have test data for the target regolith, presume it is like Earthly sand dune sand, and use the lower range of values.

Only parts of this were ever formally written down. This was mostly the engineering art that was known among those who actually did those landings decades ago. Most of them are dead now. Apparently very little of this art was passed-on, and what of it was passed-on, was lost over the time since.

GW

Last edited by GW Johnson (Today 11:14:05)

GW Johnson

McGregor, Texas

"There is nothing as expensive as a dead crew, especially one dead from a bad management decision"

Offline

Like button can go here