New Mars Forums

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

Announcement

#351 2025-12-08 07:37:23

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 23,750

Re: kbd512 Postings

For kbd512 re #350

Thank you for the reminder of the need to compare Apples to Apples.

I am calling for real numbers instead of hand waving in this forum.

The method reported for production of some result using a molecular jiggling method is one thing.

A method that produces the same exact result using another method can be compared to the first one.

Each method will have advantages and disadvantages.

One method will consume less energy than the other to produce a kilogram of product.

It seems possible to me that this forum is capable of placing into the public record information that is precise and actionable.

Update: I just renamed a topic in hopes our members will help to build up a collection of knowledge about CO2 in the Mars context.

https://newmars.com/forums/viewtopic.php?id=10930

If you have time, please create posts that contains all the information a person or group would need to implement one of the methods to work with CO2. Please keep each post tightly focused so that the reader can concentrate on one particular idea.

The jiggly method discovered by the folks at the university in South Wales might turn into an entire industry.

There are already entire industries developed or developing around carbon capture.

There are entire industries developed or developing around using pure carbon.

The NewMars environment can draw upon all existing resources and blend them into something a reader can use to solve a problem or create an entire infrastructure on Mars.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#352 2025-12-08 18:48:26

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,107

Re: kbd512 Postings

Energy requirement, mass of equipment, plus foot print volume required to send to Mars.

Repairability risk of parts not mechanical.

Offline

Like button can go here

#353 2025-12-08 21:31:52

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 8,401

Re: kbd512 Postings

tahanson43206,

I went back and actually read all of the Nature article he posted most recently. I was wrong. That one is actually related to solid Carbon production, so I'll study it in greater detail. The prior articles he's posted were related to CO production, which is great if the goal is syngas for liquid fuel production, but not for elemental Carbon. I can easily understand why he places great emphasis on liquid fuel production, though, since those are the forms of energy we consume the most of. Nearly all of the machines that do the real work necessary for cities to exist are burning diesel or natural gas, so he would rightly view production of those fuels as of greater importance than coal, which remains relatively abundant. The problem, at least as I see it, is that even coal is finite. Our ability to completely replace extracted coal with pure Carbon from CO2 would mean as long as we have access to CO2 and thermal energy from sunlight to capture the CO2, our synthetic coal supply is functionally inexhaustible. Most of the nasty stuff in coal (Sulfur, heavy metals, and radioactive elements) would no longer be spewed into the air, either.

Here's a Science Direct article using a different Gallium alloy and ceramic catalyst that also requires no external energy input to drive the reaction:

Room-temperature CO2 conversion to carbon using liquid metal alloy catalysts without external energy input

Regardless, I think I'm on fairly stable scientific ground when I assert that any chemical process which does not require any kind of external energy input is likely to be more efficient than one which does require external energy inputs, provided that there's not some other kind of serious "gotcha", such as absurdly low selectivity or an unstable catalyst or extreme energy input to obtain the catalyst in usable form or to construct the chemical reactor device. If the chemical reactor to break CO2 into Carbon and Oxygen had to be made from pure Platinum, that might make the process economically infeasible, even if the tech worked exactly as advertised without using any energy input.

I can think of various other similar reactions requiring no energy input, though.

If you drop a chunk of Magnesium Oxide (MgO) into Fluorine, the Fluorine is so electro-negative that it will break the bond Oxygen has with Magnesium, strong as it is, without any energy input at all, creating MgF2 in the process. Similarly, Magnesium metal will immediately and rapidly generate Hydrogen gas when dropped into water without further energy input of any kind.

Offline

Like button can go here

#354 2025-12-08 22:11:57

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 23,750

Re: kbd512 Postings

For kbdt12 re #353

Thanks for going back to study the Nature article, and for reporting your findings.

Pure Carbon sure does sound (to me at least) like a valuable commodity.

It can be used as feed stock for all sorts of useful compounds, or it could just be burned in air as a convenient energy store all by itself.

On Mars it seems to me that CO and O2 are more attractive for transportation because they are so easy to make and so easy to use.

It very well might be desirable to make methane or even something as complex as gasoline for special missions, but the oxygen still has to be carried along.

I've set up a topic for collecting knowledge about working with Carbon. I hope that a few members will be inspired to create posts that would be useful to future readers.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#355 2025-12-10 04:00:12

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 8,401

Re: kbd512 Postings

tahanson43206,

If you have to carry the fuel and oxidizer with you, as you would on any planet except Earth, then pure Carbon doesn't require extra Oxygen atoms to combine with the Hydrogen atoms.

Kilograms of Pure Oxygen for Complete Combustion of 1kg of fuel:

Pure Carbon (32.8MJ/kg; 1kg powdered graphite = 1.05-1.15L; 28.52MJ/L): 2.67kg (2.34L); 3.49L ttl vol, 9.40MJ/L incl O2

Gasoline (44-46MJkg; 1kg = 1.2-1.4L; 32.86MJ/L): 2.3-2.7kg (2.37L); 3.77L ttl vol, 12.20MJ/L incl O2

Kerosene (43-46MJ/kg; 1kg = 1.25L; 36.8MJ/L): 2.93kg (2.57L); 3.82L ttl vol, 12.04MJ/L incl O2

Diesel (42-46MJ/kg; 1kg = 1.16-1.2L; 38.33MJ/L): 3.4kg (2.98L); 4.18L ttl vol, 11.00MJ/L incl O2

Methane (50-55.5MJ/kg; 1kg LCH4 = 2.36L; 23.52MJ/L): 4kg (3.51L); 5.87L ttl vol, 9.45MJ/L incl O2

Hydrogen (120-142MJ/kg; 1kg LH2 = 14.1L; 1L = 10.07MJ/L): 8kg (7.01L); 21.11L ttl vol, 6.73MJ/L incl O2

LOX is 1,141kg/m^3 or 1.141kg/L

What can we conclude from that?

1. LH2 is a pretty pedestrian fuel when you need to store the cryogenic oxidizer, too.

2. There's not much difference between pure Carbon powder and Methane, except that making Methane is a lot more difficult and requires a lot more energy and technology than bubbling collected CO2 through a column of liquid Gallium eutectic. You need equipment to collect both H2O and CO2, a Sabatier reactor, a reverse fuel cell, and a really good electrical power source.

3. You do get 17% to 30% more energy per total volume by combusting diesel / kerosene / gasoline, in comparison to Carbon powder, but if you thought making Methane was energy intensive, you're going to need to add a lot more energy-intensive equipment to your chemistry set, and of course, you only get that additional energy by combusting it using additional O2 mass, which means you need to make more O2 from some combination of H2O and CO2. It's a pretty safe bet that all those additional chemical reaction steps will cannibalize whatever gains a dense liquid hydrocarbon fuel provides.

4. The relative complexity of obtaining LCO2 feedstock, on Earth or Mars, is pretty low. It's everywhere in the atmosphere and in the oceans here on Earth. Mars helps us out a bit by having a nearly-pure CO2 atmosphere, but at absurdly low density. Speaking of absurdly low density, LH2 looks great, best of all fuels, except when you must consider the mass of the storage equipment, and then it doesn't look so hot.

5. Of all the fuels listed, and any other liquid hydrocarbon fuels that weren't, if you throw a kilogram of Carbon on the ground, here on Earth or on Mars, that same kilogram of pure Carbon fuel will still be there the next day. We can't make the same claim about any of those other fuels. Carbon doesn't require special storage of any kind. If storing a cryogenic oxidizer is a pain we'd rather not deal with, then why compound the problem with fuels which also have special storage requirements?

Offline

Like button can go here

#356 2025-12-10 07:20:50

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 23,750

Re: kbd512 Postings

For kbd512 re Post #355

Thank you for the overview of fuels, with details that should help a reader to compare them.

The single most important point in Post #355 (from my perspective) is the stability/storability of pure carbon.

A practical way of using pure carbon was pioneered by humans centuries ago... I'm thinking of steam but there are surely many other applications that NewMars members can think of, or modern search tools can help to identify them.

Steam might be adapted as a practical system for Mars. Water would be too precious to vent to the atmosphere, so water vapor would have to be collected after it is used. The cold atmosphere of Mars might allow for sufficient radiation of thermal energy, but that would mean a system to produce mechanical power would need an array of fins to condense the steam. That might be practical for a fixed installation. I suspect steam will not be used for transportation systems if competitive systems are available.

CO and O2 in gaseous form appear to me to by far the most practical energy storage systems for Mars.

I'll come back to re-read your post to see if you included that fundamental pairing in your study.

I'd like see this forum show practical designs for machinery for Mars, and those designs can include all the fuel combinations you listed and any that you omitted for reasons of space or time.

For twenty plus years this forum has accumulated high level 30,000 foot visions of what might be done on Mars. A few members have published the equivalent of practical suggestions, but those are not cataloged for easy lookup.

We only have a few members active in this epoch. I've described a project that will require a lot of thought and effort. With any luck at all we may attract new members who would be willing to help to build up a repository of knowledge.

The people who are going to explore and develop Mars are alive today. The Mars Society itself is providing opportunities for those individuals to publish and present work they've done to prepare for Mars. This forum has the potential to provide a gathering place for those individuals and others to work together to build teams that will transfer easily to missions, companies or organizations.

An example of the kind of practical knowledge I would like to see in this forum would be a series on CO and O2 that would include everything a planner/funder would need to create a family of transportation vehicles and related support services for Mars. The series would include specifications for extracting CO2 from the atmosphere and making CO and O2. the series would include specifications for storing the output at the manufacturing site and delivering quantities to distribution centers. The series would include design of vehicles of various kinds, including the 10 ton trucks that SpaceNut has shown us recently, and all manner of other useful vehicles. I can imagine this collection as part of the Projects category that SpaceNut created, with as many topics as are needed to organize the knowledge so it is easy to find and to use.

It should be obvious, but just in case someone is reading this for the first time, every vehicle and every power production machine that uses CO and O2 on Mars ** will ** require tanks for both fuel and oxidizer, just as any chemical rocket does on Earth today.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#357 2025-12-10 11:23:45

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 8,401

Re: kbd512 Postings

tahanson43206,

Elemental Carbon and "CO", which is Carbon Monoxide, are two different chemicals with different properties. Elemental Carbon is a solid. It does not require a pressurized storage tank for bulk storage. Coal, which is mostly elemental Carbon, can be stored on the ground outside in the elements, because it's a solid. Carbon Monoxide and Carbon Dioxide are gases or liquids, dependent upon pressure and temperature, which does require pressurized storage tanks. Carbon Monoxide and Carbon Dioxide will both "freeze solid" when you get them cold enough, but again, you have to keep them cold, which generally implies a pressurized storage tank and cryocooler. Elemental Carbon, on the other hand, is a solid and remains a solid until it's combusted, which then forms Carbon Monoxide (partial combustion) or Carbon Dioxide (complete combustion).

Martian nights are so cold that Carbon Dioxide can and frequently does become a solid near the planet's surface, similar to water vapor becoming "frost" on cold nights here on Earth. For Carbon Monoxide to freeze, it has to be cooled to cryogenic temperatures well below what the ambient Martian environment provides at its North and South poles during the night. The described "freezing effect" is sufficient that frozen CO2, aka "dry ice", can be collected from the surface of Mars at night, even near the Martian equator during summer, for very modest energy expenditure. The dry ice is fed into an empty pressure tank, which then creates liquid CO2 (LCO2) after the tank is sealed and begins to pressurize as heat is applied. An electric heating element inside the tank would add heat to cause the dry ice to become LCO2 or SCO2. LCO2 is a dense liquid that's easy to pump, unlike dry ice. Adding a little bit more pressure using a bit more heat transforms the LCO2 into supercritical CO2 (SCO2), which does not require any pumping power to transfer the batch of collected CO2 from Storage Bottle A to Storage Bottle B, because supercritical fluids flow like gases. While LCO2 can also flow (expand) without pumping power if pressure is slowly released, so that it does not re-freeze from expanding too fast and isn't allowed to expand so much that it becomes a gas again, the speed of the flow is much more pronounced in SCO2, so tank fill / transfer operations can be very fast. For our purposes, though, LCO2 flow speeds are likely to be completely acceptable and required pumping power is very modest.

Powdered solid fuels burned by external combustion engines, such as SCO2 gas turbines, can have the solid fuel fed into the combustion chamber using CO2 gas to "fluidize" the powder. SCO2 gas turbines are external rather than internal combustion engines. The heat from burning this "synthetic coal" is indirectly fed into the SCO2 working fluid that drives the power turbine. Hot exhaust CO2 is recirculated into the combustion chamber to moderate the temperatures produced by combusting synthetic coal / elemental Carbon. The Allam-Fetvedt cycle burns coal powder or natural gas in an external combustion chamber that drives a SCO2 power turbine via a heat exchanger loop (exactly like a refrigerant loop) that carries hot expanding SCO2 through the power turbine, then back to a pump to repressurize the SCO2, and finally back through the burner. 95% of the gas fed into the combustion chamber is CO2, the remainder being pure O2 and coal powder or natural gas. The hot section of this "engine" is effectively a blow torch adding heat to a thermal power transfer fluid (SCO2) with density more closely comparable to liquid water than steam / water vapor. The 95% CO2 "atmosphere" in the combustion chamber is put there to soak up additional heat to dump into the working fluid and pumps responsible for SCO2 repressurization. This is the penultimate "lean burn" combustion engine. It does have a cold side heat sink, because like every other heat engine it has to, but it's as miserly as it possibly can be with the fuel and oxidizer.

The reason we would want SCO2 gas turbines for land vehicles is their incredible power density per unit weight and volume, as well as their ability to operate at extreme temperatures and pressures. The kerosene burning AGT-1500 conventional gas turbine that powers our M1 tank produces about 1,500hp (~1MW) and is so large that a relatively strong adult cannot pick up the turbine wheel (the rotating assembly that compresses air and expands combusted exhaust gases) with both hands because it's so large and heavy. The AGT-1500 engine's dry weight is 1,134kg, so about as heavy as a subcompact car. That same person can easily pick up a 1MW SCO2 turbine rotor with one hand, since it readily fits in the palm of their hand. The power density of the rotating machinery in a SCO2 gas turbine is "extremely extreme", meaning 1MW/kg and 10MW/L. Only nuclear thermal rocket engine core power density surpasses SCO2 gas turbine rotor power density. Large commercial nuclear reactors fall in the range of 100-200kW/L. There is no other kind of rotating or reciprocating engine with SCO2 turbine power density. The RS-25's high pressure Hydrogen turbopump's power density is about 33.8kW/kg, so even the most powerful rocket engine turbopumps, which are a type of conventional gas turbine used to force-feed propellants into liquid rocket engines, have a power density 10X lower than SCO2 gas turbines. However, SCO2 gas turbines also require other attached equipment such as heat exchangers and combustors, so overall power density is much lower than turbine rotor power density alone would suggest. However, power density for a full ceramic composite SCO2 gas turbine / heat exchanger / combustor package is on-par with a rocket engine turbopump. Since a rocket engine turbopump is only designed to feed propellants into a combustion chamber, that makes the SCO2 gas turbine more useful for powering non-rocket vehicles, particularly heavy ground vehicles like mining equipment.

For a mining truck, a SCO2 turbine would generate electricity used to drive electric motors directly powering the wheels, eliminating a lot of the heavy rotating machinery connected to the diesel piston engine of a more conventionally powered mining truck. If something happens to the engine or drive train of a conventional mining truck, that truck is a paperweight until the component is replaced. SCO2 would make the critical components compact and light enough that multiple engines could be carried for redundancy. A 10MW diesel engine weighs tens of tons, so there's only space and weight allocation for one of those diesel engines in the mining truck. A Mars mining truck could have quadruple redundant 10MW SCO2 turbine engines, but all four engines wouldn't come close to the weight and bulk of a mere 1MW diesel engine. Since solid Carbon isn't as energy dense as diesel fuel, the extra space and mass could be occupied by larger fuel and oxidizer tanks.

Anyway, I think I made my point about the various common forms and phases of Carbon and Carbon-Oxygen gases, as well as how we might use them on Mars in a more practical manner than any other fuel. We would definitely like to have Carbon-Hydrogen fuels if we can synthesize or extract them in useful quantities, but synthesizing and storing them is significantly more challenging. There's no way around that. If conventional gasoline or kerosene synthesis proves to be a "bridge too far" until the colony is more highly developed, we now have a simpler and less energy-intensive alternative that wasn't available before- fewer energy sinks, fewer pieces of equipment, fewer people to operate it, and fewer failure modes. Here on Earth we have easy access to enormous amounts of liquid water that simply doesn't exist anywhere else, so far as we know. Even if we find ice, we still have to extract, melt, purify, and transport the water. Since transportation cost will remain an issue for quite some time, why complicate fuel synthesis when you don't have to? The benefits of adding Hydrogen to Carbon are marginal when you have to expend additional energy to make the Hydrogen and attach it to the Carbon. The entire purpose behind creating chemical energy stores is to use them for other useful work unrelated to dumping energy back into the energy generating and storage systems. This is merely another way of saying that we don't create energy storage products to justify creating additional infrastructure required to create more of said energy products, because we know that energy invested into energy storage is always a losing proposition, unsustainable past the point where energy must be devoted to other uses such as purifying drinking water, food, shelter, clothing, etc. If obtaining 1kg of Uranium to fission in a reactor required expending the energy equivalent of 10kg of Uranium, then there would never be a commercial electric power plant powered by a fission reactor. That's effectively what Hydrogen synthesis entails on Mars. The only rational reason we would want to do something like that was if a Hydrogen powered rocket was the only feasible way to leave the surface of Mars to come back to Earth. Powering someone's personal car or home that way makes even less sense- something to be done only in the complete absence of more energy-input-favorable alternatives.

Offline

Like button can go here

#358 2025-12-10 11:49:45

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 23,750

Re: kbd512 Postings

For kbd512 re Post #357

This post seems (as I read it) to contain numerous points in support of using solid carbon as a chemical energy storage material in combination with oxygen.

I think that there might be enough knowledge in existence today to guide a person or a group toward design and construction of a practical combination of chemical processing services to supply the carbon and oxygen for a transportation or work system.

This forum is as good a place as any for a repository of that knowledge.

I am in favor of this repository, and willing to support a NewMars member who would like to build it.

Such a repository would NOT consist of hand waving or Rosy Scenarios. It would consist of proven examples of each technology, and exact steps needed to replicate whatever it is on Mars.

This forum has been in the fantasy business for two decades and unless something changes it will continue creating exciting visions for entertainment.

I consider CO and O2 to be chemicals that will inevitably become major players in the transportation and energy storage infrastructure on Mars, so I would like to see a knowledge repository in which their production and use are clearly defined so that a person or a group can replicate them on Mars.

A far more technically sophisticated individual or group might well elect to pursue the many advantages you've laid out, so a repository supporting an advanced technology would surely be of value.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#359 2025-12-10 16:16:30

- Calliban

- Member

- From: Northern England, UK

- Registered: 2019-08-18

- Posts: 4,279

Re: kbd512 Postings

To make carbon monoxide, carbon must be burned in an atmosphere with limited oxygen. This releases about 20% of the heat released by complete combustion. The process that Kbd512 has described produces particles of carbon. So that is what we start with. Carbon monoxide has important uses of its own. One such use is the production of reduced iron. Making strong engineering bricks is another use we have noted. But it is a precursor to other more convenient fuels. For example:

CO + H2O + heat = CO2 + H2

2H2 + CO = CH3OH.

This is methanol. It is a clean burning liquid fuel that doesn't freeze until -97°C. We could store it in tanks on Mars with very little pressurisation. By using the appropriate catalyst, methanol can form dimethyl ether:

2CH3OH = H20 + H3C-O-CH3.

Dimethyl ether has been considered as a diesel substitute. It would make an energy dense rocket fuel that is less volatile than methane.

Last edited by Calliban (2025-12-10 16:21:50)

"Plan and prepare for every possibility, and you will never act. It is nobler to have courage as we stumble into half the things we fear than to analyse every possible obstacle and begin nothing. Great things are achieved by embracing great dangers."

Offline

Like button can go here

#360 2025-12-19 20:24:41

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 23,750

Re: kbd512 Postings

For kbd512 re fighters and missiles https://newmars.com/forums/viewtopic.ph … 34#p236334

Nice! That one was worth reading all the way to the end!

That was ** some ** F16 pilot!

As a follow up ... how did that pilot drop so much air speed so quickly? I suppose a climb might have that effect but perhaps there is something else?

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#361 2025-12-21 03:38:48

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 8,401

Re: kbd512 Postings

tahanson43206,

The pilot who was shot down, Jeff Tice, describes his ordeal here:

His F-16 (Stroke 1) was shot down. Another F-16 coming the other direction, that he tried to warn because he saw the launch, was shot down and converted into metal confetti on that mission. That pilot did not survive. One of his wingmen (Stroke 3), was the one who dodged 6 SAMs. Needless to say, the Iraqis got his attention after shooting down his flight lead.

A lot of things went wrong, to put it mildly, but that's how it goes. No matter how carefully you plan something, that typically goes right out the window the moment the shooting starts. He sent 4 of his wingmen home, one who became "lost", so he detached him and another jet to escort him. Another F-16 suffered a mechanical failure of some kind, so he sent detached another jet to escort him home as well. In the end, he was effectively down to the flight leads in the formation he was leading to prosecute the attack against their target. Keeping the most experienced pilots turned out to be a good thing, because things got "interesting" really fast. Jeff Tice was previously a F-111 pilot and DACT instructor in the F-5, I think.

There were actually some 74 airplanes in the mission package, with different flights assigned to multiple different but relatively geographically co-located targets near Baghdad. Some were there to attack an airfield, while he and his wingmen were attempting to hit an oil refinery. F-15s were assigned as "top cover" to perform a pre-strike fighter sweep so that the ordnance-laden F-16s would, hopefully, not get jumped by Iraqi MiGs. F-4 Wild Weasels were also present to attempt to suppress enemy air defenses. I've no clue if any EF-111As or EA-6Bs were also present to actually jam enemy SAM radars rather than attacking them with HARMs after the fact, but since they had so many SA-6s fired at them, I'm guessing not. ROE was visual identification of targets before dropping ordnance. They had dumb bombs, mostly 2,000lb Mk84s, not LGBs, and I don't think JDAMs existed back then. Believe it or not, it was actually cloudy during the first week of the war, so many of the jets had to abort their attacks because they could not see their targets.

I can't speak intelligently on what the US Air Force allows or does, but the US Navy is still very big on accuracy with dumb iron bombs, which they regularly practice. Even if you think you have a target fixed, they still want visual confirmation before you take a shot at anything. Maybe we're just dinosaurs, but you'll remember a fratricide incident until the day you die, hence the rules about visual confirmation.

Jet and his wingmen dodged about 40 SAMs fired at them during the first night of Operation Desert Storm. He describes exactly how you avoid a SAM hit, which involves a correctly timed hard evasive maneuver that takes advantage of the turning circle advantage I previously described, plus another little tidbit of info about how you can effectively cut the number of gees the missile can pull in half by forcing it into a kind of turn where it can only use 2 out of 4 control surfaces to maneuver with you.

Today we have an amazing Combat Story from a 28 year F-16 fighter pilot, Jet Jernigan. Jet’s story is remarkable from how he stumbled into aviation to eventually lead the first 20 F-16s into Kuwait in the Gulf War to take out 10 Surface-to-Air (SAM) Missile sites and clear the way for Air Force bombers.

Jet and his 19 wingmen evaded over 40 SAM launches in just a 9 minute period in what can only be described as organized chaos. He would go head-to-head with SA-2s, SA-6s, and SA-9s in a span of just a few months.

As a member of the South Carolina Air National Guard, it seems unlikely that Jet’s unit was chosen ahead of other Active Duty Air Force squadrons to be the first F-16s into Kuwait. Fortunately, Jet and his team had just won Gunsmoke, the Air Force’s preeminent international aviation air-to-ground combat training exercise despite flying older F-16s against the Active Duty Air Force’s modernized variants, proving they were equally capable aviators.

Jet had many firsts in his career, including being the first Air National Guard pilot to attend the Air Force’s elite Fighter Weapons School where, with his high school degree and Air National Guard pedigree, finished as the honor graduate or Top Gun.

Jet is an incredibly humble, accomplished, and god fearing veteran who continues to live out a Hollywood-like story. Stay tuned to the end of this episode to hear Colin Powell’s very own description of when Jet was interviewed by a reporter just after landing from his first mission in the Gulf War…it says it all.

I wasn't even aware that the USAF had a "Fighter Weapons School", but I also don't know much about the Air Force. We have a "Fighter Weapons School" in the Navy, which used to be in Miramar. If they do have one similar to the Navy school, then it must be their own response to the training failures experienced during the Viet Nam War.

Edit:

In case the point isn't clear, these are two different stories involving different pilots from different units at different points in the war. In both cases when the pilot who is the target of a missile attack is aware of the attack and can see the incoming missile(s), he can use the maneuverability of his plane to evade the incoming missile(s). If you're not aware or don't see the missile, then you're about to have a very bad day.

In both cases the jets being attacked were subsonic and remained subsonic. Going supersonic would have made their jets much less maneuverable. My conclusion is that the ability to "go supersonic", never mind going Mach 3, is not a particularly useful combat capability for a fighter to have. Using excess thrust to recover energy (lost airspeed) rapidly after a hard evasive maneuver is very important, as is the ability to maneuver violently when defending against a missile attack.

My point is that modern piston engines and turboprop engines would put a fighter-type aircraft in the "sweet spot" for hard maneuvering combined with rapid-enough displacement (how far the aircraft travels per second) to avoid warhead blast radii, because that giant propeller would provide the ability to rapidly recover energy rapidly while offering much better cruise efficiency from sea level to about 40,000ft. I realize that might not be as "cool" as flying at Mach 3 around 70,000ft, but I also question the military utility of that capability unless it's a recon aircraft flying high and fast as a missile avoidance tactic, which might not work as well against modern SAMs.

The cost of the engine itself, the maintenance / repair components cost, and the fuel burn rate all tend to be substantially lower for piston and turboprop engines. I don't want to give the impression that these things can be had for pennies on the dollar, merely that if one thinks a turboprop is expensive to purchase and maintain, then they're in for a very rude surprise when they enter the after-burning turbofan world. If IR signature reduction matters at all, pistons and turboprops also tend to be less noticeable than low-bypass turbofans suitable for modern fighter jets. There are probably 2 to 4 or even more different types of aircraft which all share a common piston or turboprop engine, for each low-bypass turbofan application, which is effectively limited to military applications, typically a single type of aircraft. F135s are only found in F-35s, F-119s are only found in F-22s... F-15s and F-16s technically "share" a common engine, except that they don't. Hornets and Gripens "share" the same F404 or F414 engines, except that they don't. These days, every large military turbofan used is a bespoke design for a bespoke airframe. This means production numbers are very low and costs are very high. F-135 is a bespoke $20M+ engine that's only available from a single source and not used by any other combat jet.

For nations like Canada that want an effective defensive capability but have never had the budget or manpower to operate something as complex as the F-22 or F-35, modern engines / materials / electronics miniaturization provide a pretty compelling case for foregoing the gadgetry incorporated into the latest and greatest American and European fighter jets in favor of more affordable home-grown solutions that can (mostly) be locally produced and operated on their own terms. Supersonic capability is a major design compromise that greatly detracts from other flight characteristics that are far more frequently utilized by combat jets during real world combat, such as maneuverability, range, loiter time, and lower approach and stall speeds to improve safety during critical phases of flight. Checking that supersonic box doesn't make for a better fighter in all but the most narrowly defined use case scenarios. Kids ask how fast the jet can fly. Trained military personnel with flight experience want to know how stable the plane is on a crosswind approach, where the jet can takeoff and land, how long it'll be down for maintenance between flights, and its fuel burn rate.

Every military operation I've seen has demonstrated that drones can be effective force multipliers, but they're no more "magic totems" than stealth aircraft are. If the asset is available when and where required, then we'll find a way to exploit its strengths and live with its limitations. Predators can't fly very fast, but that "remain aloft for 24 hours" feature tends to get used quite a bit more than firewalling its throttle. Drones still get shot down, their cost is directly tied to performance and capabilities, and as of yet they're not suitable replacements for crewed aircraft. What is badly needed is more affordable crewed aircraft so that aircrews accumulate enough flight time to become proficient at using their plane as a weapon.

Last edited by kbd512 (2025-12-21 05:45:37)

Offline

Like button can go here

#362 2025-12-27 15:23:24

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 23,750

Re: kbd512 Postings

For kbd512 re next Google Meeting ...

We have an opportunity to discuss the future of NewMars.com/forums this Sunday evening, December 28th, at 8 PM New Hampshire time.

I will invite all other admins, and of course the meeting is always open to registered members.

We are down to just the four Admins and three moderately active members (Void and GW Johnson, and certainly Calliban)

I am hoping we can discuss how we might want to bring new people in, or if we want to keep this a very small group as it is now.

If we do decide we want to bring new people in, we need to have a better understanding of what value this group might provide.

If we bring new people in we run the risk of bringing in people who have ** very ** different ideas from those routinely expressed here.

On the other side of the ledger, we have brought new people in but none have stayed very long.

Steve Stewart participated, as did PhotonBytes.

Our archives are the better for the time they spent with us.

Never-the-less, this forum is NOT where they are spending time these days.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#363 2025-12-27 18:56:56

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 8,401

Re: kbd512 Postings

tahanson43206,

The general public views space exploration as a special interest group that they will never become a significant part of. There's no shortage of new or old ideas, but there is a real issue with captured interest because nobody has gone anywhere new or done anything different enough from the norm to capture the public's attention. If / when we finally go back to the moon and onto Mars, then space exploration will once again become part of the public discourse regarding what we can or should do.

Offline

Like button can go here

#364 2025-12-27 19:49:33

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 23,750

Re: kbd512 Postings

For kbd512 re #373...

Thank you for your thoughtful reply!

This forum started as a GeeWhizWhoopeeWow kinda place.

My impression is that the time for that is past.

The forum has an opportunity to serve those who will be traveling to Mars to visit or to stay, ** and ** the much larger group who will be building businesses to make that future happen.

We could stay a small group of older folks (excepting Terraformer) who will chat amongst themselves until we kick the bucket.

Or we could transform this entity into a pipeline for talent and a vital point for information exchange and for mission planning.

If we had a huge active membership doing GewWhiz things, perhaps I would feel differently, but we don't.

Again, thank you for thinking about the future of the forum.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#365 2025-12-30 14:11:35

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 23,750

Re: kbd512 Postings

For kbd512 re https://newmars.com/forums/viewtopic.ph … 15#p236715

Thanks for your reminder of baffles to improve thermal energy flow.

I'll add that item to the Todo list for 2026. It has taken a while to persuade the model to work at all, and then correctly.

The immediate next step is to reduce the throat diameter.

Your suggestion of baffles might match up with the simulation option we evaluated along with the washer variation.

That porous membrane option sounds a bit like the baffles you've shown us.

I don't know enough about it but we have an entire year ahead to learn.

You are (probably) the only person on Earth who understands the posts in OpenFOAM I've added recently.

I think GW would but I suspect he is buried in ramjet work. He has two clients now.

We are coming up on the New Year so I'll wish you and the family a Happy one!

***

I haven't forgotten the fiasco at the last Google Meeting. I had procedures in place but all of them failed in the face of new challenges.

It doesn't help that Google changed their interface just enough to throw me off balance.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#366 2026-01-02 07:35:50

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 23,750

Re: kbd512 Postings

For kbd512 re helpful post in Garage topic ...

https://newmars.com/forums/viewtopic.ph … 70#p236770

Thanks for helping with focus! The design space is large, and resources are limited.

It seems to me this topic (garage on Mars) has potential to flow in more than one direction.

The excavated volume option provides many distinct advantages.

Those include radiation protection which SpaceNut has been concerned about.

In addition, durability is a long term benefit.

The tradeoff is energy required to build it (unless a cave is found, which for planning purposes cannot be assumed).

While the cave is being excavated, the equipment needs a garage for maintenance.

It seems to me the primary purpose of a garage on Mars is to provide a well lit workspace protected from Mars surface conditions.

Radiation protection is important if humans are going to be working in the space, but I think that is unlikely to be the first choice for expeditions planned in 2026.

It seems to me that SpaceNut's topic can naturally split into at least three projects:

1) Simple popup shelter imported from Earth and assembled on Mars by robots (with and without teleoperation)

2) Simple popup shelter with radiation protection (regolith cover)

3) Excavated volume - top of the line facility with all the bells and whistles

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#367 2026-01-03 01:14:27

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 8,401

Re: kbd512 Postings

tahanson43206,

SpaceNut's going in his own directions with his own topic, which he's entitled to do. He's focused on some things you don't want him to focus on, but if that ultimately helps him to circle back around to the central idea or theme of the topic, then so be it. Maybe he's right to focus on radiation or robots or whatever, or maybe not.

Why can't we develop topics as stream-of-thought, and then selectively edit or break them into sub-topics at a later time?

To the extent that any concept can be refined into a single coherent topic with zero deviations, I think that's great, but so much about space exploration and colonization involves multi-domain problem sets that I don't know how well that would work in actual practice.

If you want to edit my posts in that topic and put my ideas where you think they should go, I would not care. I wrote down my ideas, however disorganized. Some parts of them may not be where you think they belong. I would not be the least bit offended if you moved them to where you want them. I don't get too wrapped around the axle about this stuff. I can readily acknowledge that you probably have much better topic organizational skills than I ever will.

Offline

Like button can go here

#368 2026-01-03 07:55:18

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 23,750

Re: kbd512 Postings

For kbd512 re #367

Thanks for your perspective...

As we head into the new year, and since you are in a leadership position in this very small group, please think about what the mission of this entity might be. I don't expect you to actually write anything or post it, but please think about it.

I think the essence of your vision for the group and for the entity itself is right there in Post #367

It may be that there is no hope of adding new members to this entity.

Perhaps we will continue as we have for the next entire year.

After all, we've completed the last full year with the core group in place. We brought in two new people but neither became part of the flow. One didn't contribute at all, after making a fuss about seeking membership.

I had hoped this entity might become a useful resource to others who will be heading to Mars or working on projects to reach that goal.

Having false advertising in topic wording must surely lead to any reader giving up on the forum as a useful resource.

If the purpose of the entity is to provide a private blog for members then that in itself may have value.

If someone applies for membership in 2026, what should I tell them about the entity they would seek to join?

What value could this entity bring to them?

What value would they bring to the entity?

Mars Society is investing in this entity. What is their return for that investment?

If a regular member of this forum has an opinion one way or this other, this topic is available for a post.

If a reader who is NOT a member has an opinion, use the Recruiting Portal to contact us.

Afterthought ... perhaps this is a good time to reschedule the "Like" feature update to the forum software. The forum software does not currently support feedback to members about posts. We put the kernel of the feature in place when we updated the software. Perhaps there is a member whose posts are valued by readers. At present we have no way of knowing.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#369 2026-01-05 07:56:58

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 23,750

Re: kbd512 Postings

For kbd512 re backups ....

Hopefully we are taking regular backups of the forum database.

Please take a moment to be sure the backup procedure is working.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#370 Yesterday 09:06:52

- NewMarsMember

- Member

- Registered: 2019-02-17

- Posts: 1,860

Re: kbd512 Postings

For kbd512 ...

Of our current membership, I think you may be the best qualified to evaluate the work reported by a recent visitor to our recruiting portal.

https://newmars.com/forums/viewtopic.ph … 20#p236920

I am reminded of some of your many posts about SCO2, which is a liquid with properties you have described in detail on several occasions.

It seems unlikely to me that we (this forum) can assist this gent in finding paying clients, but perhaps we can at least provide encouragement.

(th)

Recruiting High Value members for NewMars.com/forums, in association with the Mars Society

Offline

Like button can go here

#371 Yesterday 10:45:05

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 23,750

Re: kbd512 Postings

For kbd512 re new applicant ...

Thank you for your encouragement: http://newmars.com/forums/viewtopic.php … 28#p236928

When you can find some time, please investigate to see if this self-educated person is a genius or a crackpot.

I have no way of telling the difference.

I don't think this gent has any specific interest in us. I think we were on a search list to try to find paying customers.

We are unlikely to be worth any of his time, but perhaps we can find a small role in career path development.

What I am hoping we might do is to provide a venue for team building with Mars as a major theme, while making money on Earth is the vehicle.

We have the potential to attract and retain top talent on Earth, if we can provide an environment that supports success and helps folks through failure. Failure is a constant in gaining skill. We humans have been trying and failing for a very long time, and the end result is the level of civilization we've achieved, frail as it is.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#372 Yesterday 20:50:10

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 8,401

Re: kbd512 Postings

tahanson43206,

I'm not sure if he understands how significant the friction and Reynolds losses will be in the sort of machine he's proposing. Have you noticed that all geared turbofans use reduction drives to power the fan or prop, but nobody puts anything like what he's envisioning in the hot section of the turbine where the hot gas is expanding? Gears, hinges, and whatnot in the part of the machine that's hot enough to melt Iron typically don't last very long. The only reason hot section components don't melt in modern turbines is that they use boundary layer cooling, thermal barrier coatings, and smooth flow through the core.

If someone thought they could extract significant additional power, they'd not-so-simply work out how to make a mechanical advantage device work. Even in the context of steam turbines operating at more survivable temperatures, said mechanism is still likely to fail. There are basic fluid and thermodynamic phenomenon that would "sap power" from the device he wants to create, even if the mechanical bits don't overheat and warp.

While it may not be technically impossible, there are easier and simpler ways to extract more power from expanding gas. This kinda reminds me of the Librato (sp?) engine. That guy actually built one, and technically it was more thermodynamically efficient than a conventional diesel piston engine due to the mechanical advantage the mechanism provided, but it also vibrated itself to death when scaled up, even though it kinda sorta worked at a very small scale. There have been all manner of novel mechanical advantage engines designed to extract additional power, but most of them end up being more trouble than they're worth.

Whenever engineers want to increase energy conversion efficiency, they increase the temperature delta and/or add another row of blades to the expansion turbine to extract more power. They stop when the mass / size of the expansion turbine becomes impractical, and instead use the hot exhaust effluent to flash water to steam to run a geared steam turbine in a secondary power transfer loop. This is a good system for a stationary power plant of even a ship with a high quality heat source, such as a gas turbine engine.

Chrysler used a large recuperator stage to make their automotive gas turbine more efficient because more turbine blades were and are expensive, but had to stop when the thing filled the engine bay. They also used "blade disks" or "blisks" vs traditional individual turbine blades, because a blisk is a single near-net-shape casting which minimizes finishing machining operations. At 410lbs, the turbine was still lighter than an all-Iron V8, but not by a lot, it burned a more expensive fuel, even though it could technically run on Chanel No 5, and on top of that it was made from precision machined refractory metals that could not be repaired by shade tree mechanics. Fuel economy at idle with a gas turbine is horrific, even today. The turbine engine ultimately made 130hp and 425-450lb-ft of torque. The torque was phenomenal for the time, so acceleration to highway speeds was very respectable, but total power was also very limited. Once you're on the highway, passing a slower driver is more difficult. It would've been fine for 55mph, but passing someone at 70mph going up a hill would be difficult. Unfortunately, all of the materials tech added up to an engine that was much more expensive than an equally capable gasoline fueled piston engine. I think it would still be more expensive using modern manufacturing tech. Modern piston engines are mostly cast Iron moving bits / Aluminum for blocks or heads or covers / plastic for intake manifolds since it heats soaks less than Aluminum. Those are the cheapest and lightest materials that get the job done, and they do the job admirably.

The all-Aluminum LS1 V8 engine from the turn of the century made 305-350hp and 335-365lb-ft of torque. The most modern 6.6L L8T version of the LS engine architecture makes 401hp and 464lb-ft of torque. These all-Aluminum engines also weigh about 400-425lbs, fully dressed, without fluids. They're weight-equivalents of that Chrysler turbine, about the same size, make considerably more power, burn less fuel, burn gasoline instead of kerosene or diesel, and don't cost nearly as much to manufacture as a gas turbine because nearly every part of the engine is a casting or powdered metal part or plastic. Modern casting and powdered metallurgy is so good that it's considerably stronger than the more expensive low-alloy steel forgings from the muscle car era. The factory forged crankshafts and connecting rods from the muscle cars are not as strong as the modern stuff. We used so many forgings for so long for sake of consistency of forged parts.

We quit considering small gas turbine engines because of the aforementioned idle fuel consumption problem combined with the fact that none of them are significantly lighter or smaller than equivalently powerful piston engines. Modern turbocharged I4s are cranking out 200-250hp and 250-350lb-ft of torque and only weight about 250lbs with fluids and accessories. Gas turbines can be made lighter, but only when idle fuel economy, service life, and cost considerations are tossed out the window. Gas turbines still work great for mostly steady-state applications like aircraft and electric power plants.

Offline

Like button can go here

#373 Yesterday 21:59:29

- NewMarsMember

- Member

- Registered: 2019-02-17

- Posts: 1,860

Re: kbd512 Postings

For kbd512 re #372

Thank you for your essay on turbines and piston engines! That piece is worth remembering, so I will create a bookmark.

I've given up on the gent from Mexico. Your assessment of his designs reinforces my decision to decline his bid for membership.

We may have to go a bit longer into 2026 before we pick up our first new member.

***

Just FYI ... I am preparing to test the extendedMerlin at 1 kg/s. ChatGPT5 thinks we will see much improved ISP.

I am running one more 1 second sprint to see if the current 2 kg/s model converges at 2 kg/s out for 2 kg/s in. It is within a tiny fraction at 15 seconds, but I wanted to try "just one more" time to see if the system would settle. It has spent several seconds building up mass in the intake but that process too seems close to a peak.

I'll start the 1 kg/s run from zero, and try to have something to show on Sunday.

The argument ChatGPT5 gives for encouraging this experiment is that this design should be able to throttle over a wider range than an ion engine given the same power input. We've seen already that we can get 10 times the thrust by increasing mass flow from 2 kg/s to 20 kg/s, just as Gw predicted. And ** that was ** with an engine running on fake heating. For our readers who might be seeing this for the first time, in that version of the extendedMerlin model, we were not yet heating the gas with solar energy. Instead, we were using fake heating from 20 Kelvin to 300 Kelvin. That was part of the CFD shakeout process. Now, with 40 MW of intentional heating, we are getting 1 ton-force from a flow of 2 kg/s and an estimated ISP of 250. I'm not certain of that figure because I haven't requested an ISP calculation for a while.

ChatGPT5 thinks we should see ISP near 460 or so with 1 kg/s, and thrust of about half a ton-force. If you are flying the vessel, the higher ISP should mean you get more run time for that thrust, or more momentum transferred to the vehicle, or perhaps both. I'm not sure about that.

Thanks again for your detailed essay on engine type and performance!

(th)

Recruiting High Value members for NewMars.com/forums, in association with the Mars Society

Offline

Like button can go here

#374 Yesterday 23:51:33

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 8,401

Re: kbd512 Postings

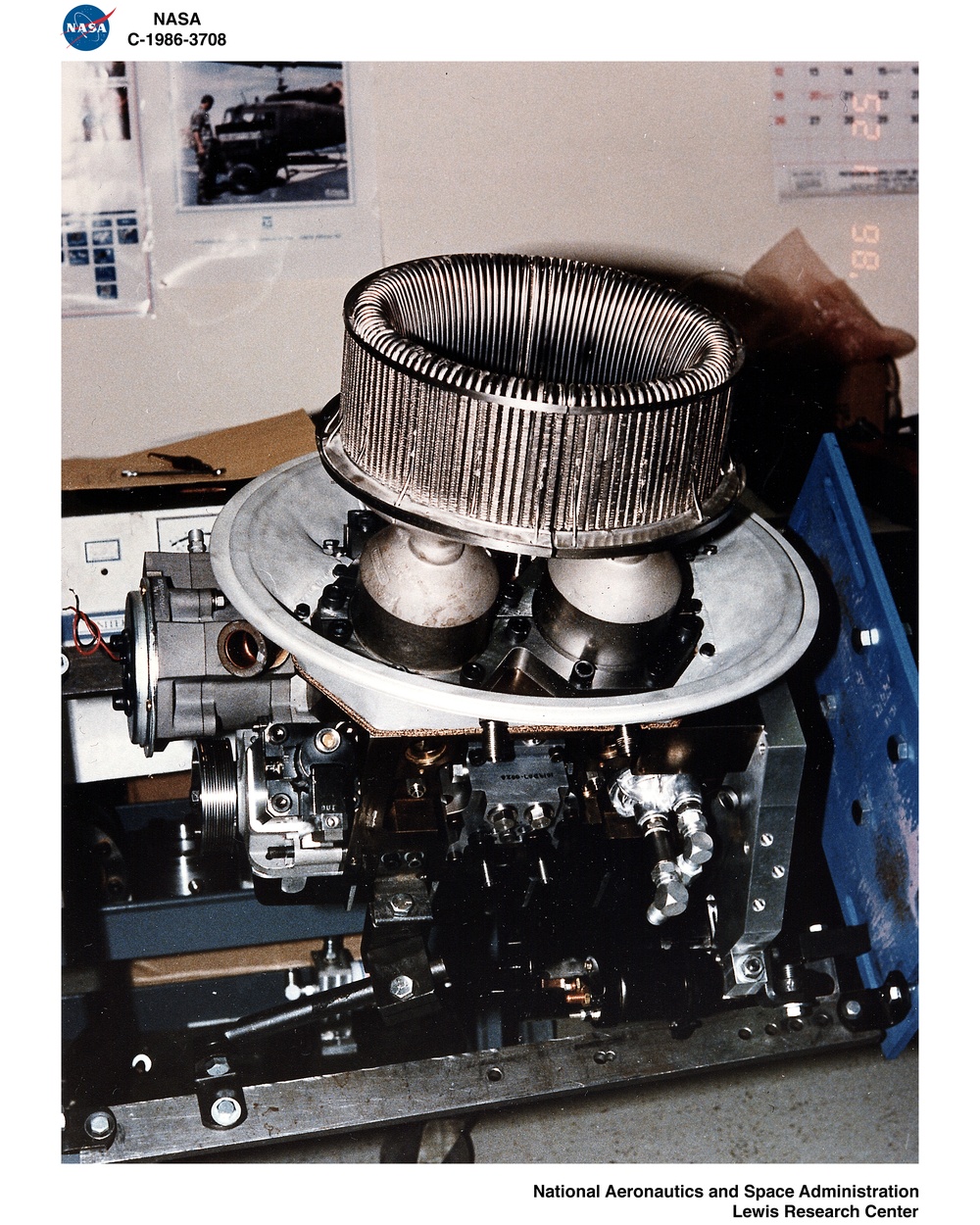

Lest we forget our automotive history, here are a few images of the Chrysler recuperated gas turbine car engine:

Engine installation at the factory:

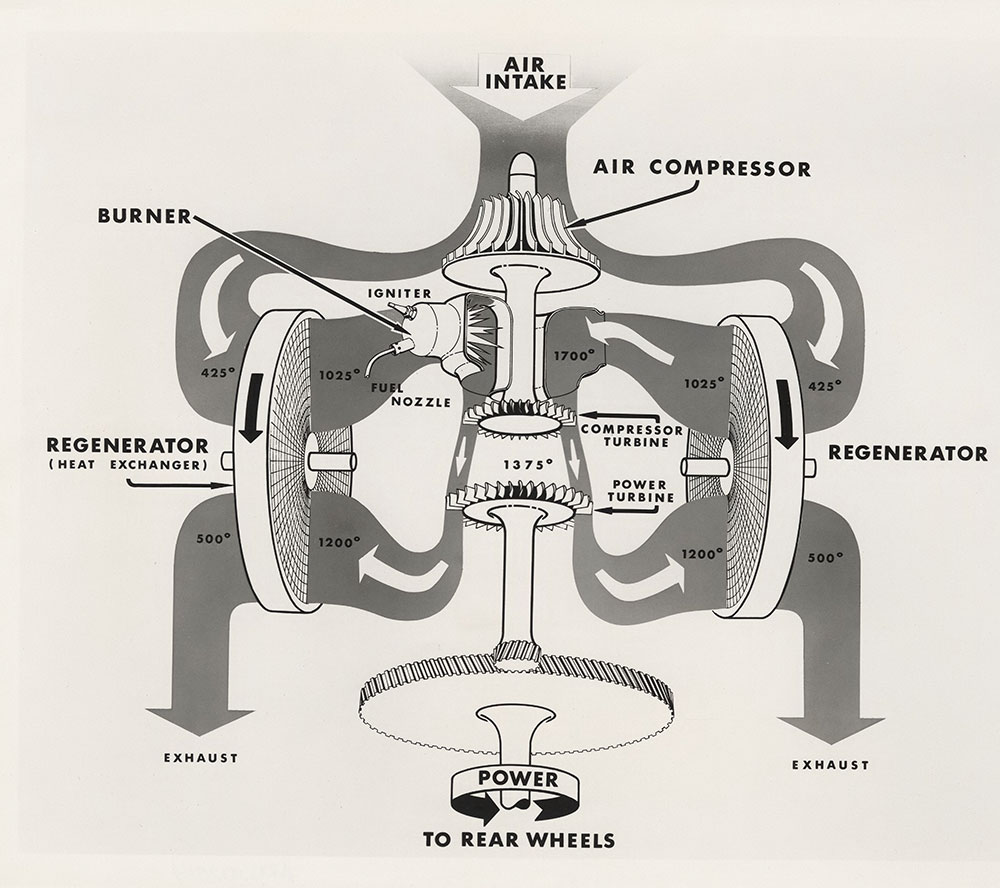

Flow Path / Operating Diagram:

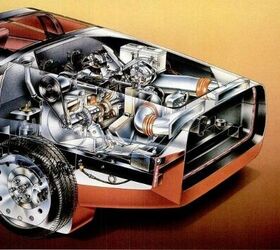

Recent photos of the engine and transmission:

Older photo of the intake side:

Engine Diagram:

Vehicle Powertrain Diagram:

Chrysler went through 7 generations of gas turbine engine technology in an attempt to make the tech reliable, durable, affordable, and fuel efficient enough to be worth manufacturing for the general public. Unfortunately, their efforts never resulted in a saleable product. When Lee Iacocca took the bailout from Uncle Sam, part of the deal was to kill this program because Chrysler sunk a huge amount of their R&D budget into its development.

General Motors had their own turbine powered concept car, but again, development was insufficient to result in a saleable product.

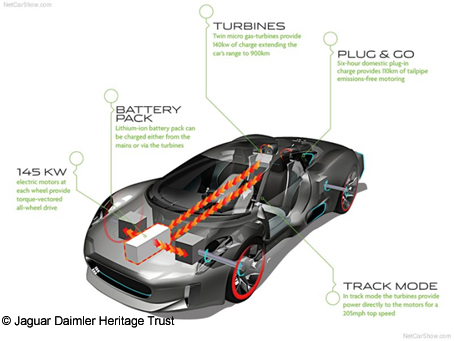

Jaguar attempted a gas turbine electric powered car, also amounting to nothing. A few prototypes were built and tested, nothing more.

As an electric hybrid using a micro gas turbine + small battery + electric traction motors, the concept actually makes a lot more sense.

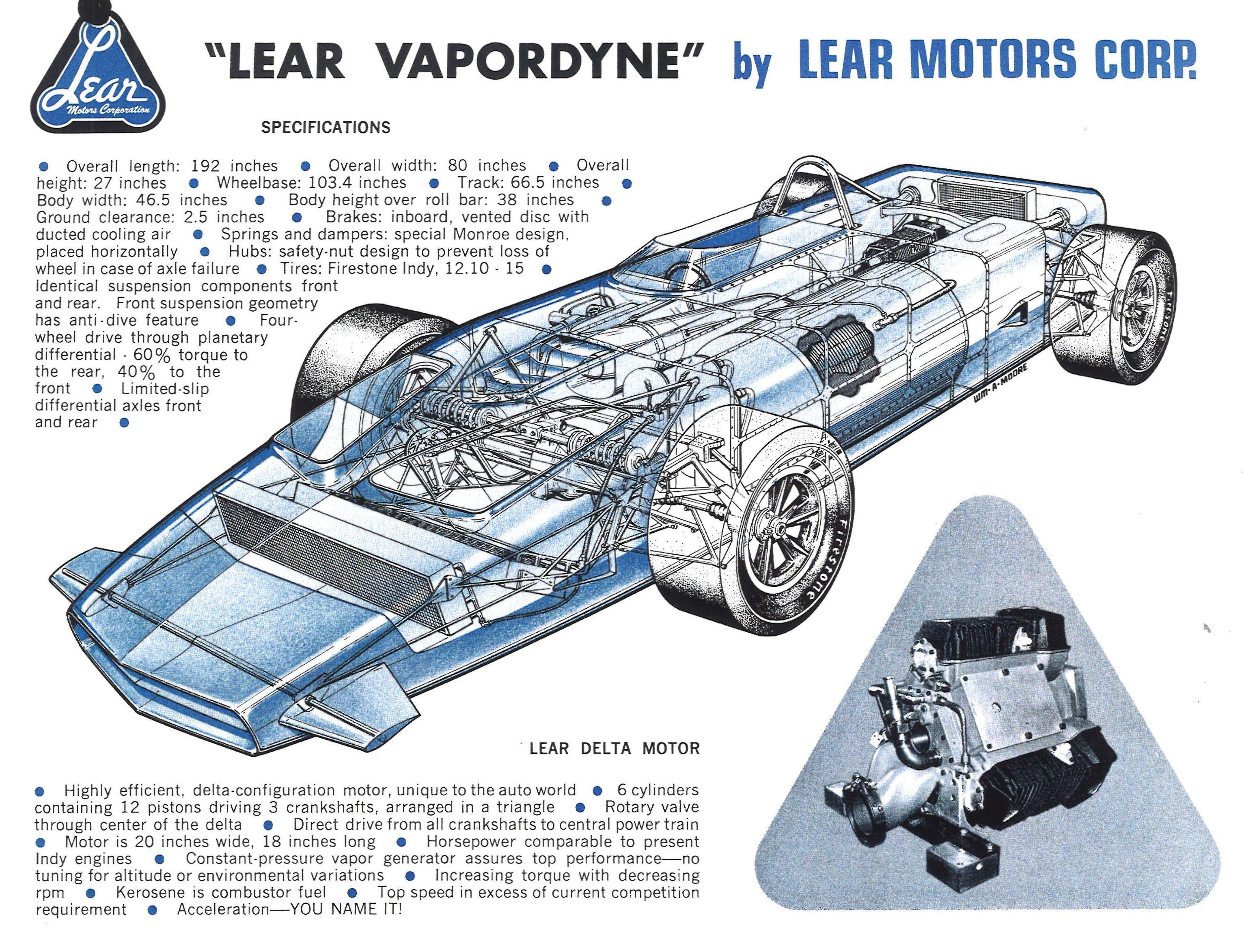

The LearJet bubbas worked on this thing:

In the 1960s, everyone thought gas turbines would power everything:

Bill Bessler built a steam powered car for General Motors in the 1970s. It's primary claim to fame was dramatically reduced smog emission prior to catalytic converters, but fuel economy was only 15mpg. Dutcher worked on a steam powered car for California in the 1970s as well.

US DoE tested a Stirling engine car in the 1980s to early 1990s:

Could we get better performance from gas turbine an external combustion engines using modern FADEC technology?

Probably.

Will they ever be as cheap and cost-effective as piston engines at output below about 550hp or so?

Possibly, but not likely. The materials and manufacturing methods used to deal with the heat are expensive, full stop.

Offline

Like button can go here

#375 Today 00:36:36

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 8,401

Re: kbd512 Postings

As far as "beyond piston engines" is concerned, not to beat a dead horse, but I truly believe that the absolutely incredible power density of Supercritical CO2 systems is the most likely contender. A 250kW (335hp) SCO2 gas turbine rotor is roughly the same size as the US Silver Dollar. The heat exchanger power density can reach 700MWth+ per cubic meter. That means the power turbine, burner, and heat exchanger assembly can be roughly the same size of a shoebox. It'll be relatively heavy if made exclusively of refractory metals vs RCC, but as far as compactness and thermodynamic efficiency are concerned, nothing else comes close.

My contention is that hybrid electric powertrains are not only possible but truly practical using SCO2 gas turbines and small Lithium-ion battery packs. At 160Wh/kg, a 26kg battery pack is sufficient for 60 seconds worth of stored electricity to allow the motors to quickly accelerate to highway speeds.

Alternatively, a purely mechanical powertrain using a CFRP flywheel could store 1.976kWh in a 26kg flywheel and deliver a 130kW / 174hp burst of power for rapid acceleration. The SCO2 gas turbine could be truly tiny. Now that we have geared CVTs, this new transmission tech would permit optimized power delivery without electronic shifting.

Last but certainly not least, the dramatic simplification of the powertrain using either of these solutions could make cars significantly lighter.

Offline

Like button can go here