New Mars Forums

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

Announcement

#26 Re: Exploration to Settlement Creation » Proposed Superdome construction in a Crater » 2026-01-15 18:05:39

Mars is mostly iron but it needs smelting and shaping equipment in order to build such a insitu material shape.

#27 Re: Human missions » International Space Station (ISS / Alpha) » 2026-01-15 18:02:18

Hiding behind HIPPA

Illness on the ISS is common due to microgravity affecting fluids, immune systems, and balance, leading to issues like motion sickness (Space Adaptation Syndrome), skin rashes, respiratory infections, and vision/bone changes, with a recent unprecedented medical evacuation of Crew-11 in January 2026 for an undisclosed serious condition highlighting the risks, though astronauts manage many ailments with Earth-based telemedicine and onboard kits.

Common Health Issues in Space

Space Adaptation Syndrome (SAS): About 50% of astronauts experience nausea, headaches, and disorientation as the inner ear readjusts.

Fluid Shifts: Fluid moves to the upper body, causing sinus congestion, puffy faces, and potential vision problems (SANS - Spaceflight-Associated Neuro-ocular Syndrome).

Immune Dysfunction: Microgravity can weaken the immune system, making infections more likely.

Skin Rashes & Respiratory Issues: These are frequently reported, often due to changes in the immune system or close quarters.

Bone & Muscle Loss: Long-term exposure weakens bones and muscles, requiring strict exercise.

Radiation Exposure: Cosmic rays can affect DNA repair and energy use, with effects lingering after return.

Recent Medical Event (January 2026)Crew-11 Evacuation: Four astronauts (Zena Cardman, Mike Fincke, Kimiya Yui, Oleg Platonov) returned early from the ISS due to a serious, undisclosed medical event involving one crew member.

Unprecedented: This was NASA's first controlled medical evacuation from the ISS, though models predicted such events occur about every three years.Management & Preparedness

Onboard Medical Kits: The station carries medicines and equipment like ultrasound scanners.

Telemedicine: Crews consult with doctors on Earth for diagnosis and treatment.

Limitations: The ISS lacks full hospital facilities like an MRI, necessitating evacuations for severe issues

#28 Re: Meta New Mars » Housekeeping » 2026-01-15 16:04:08

I think that I got them all

#29 Re: Exploration to Settlement Creation » Calliban's Brick Dome on Mars » 2026-01-15 15:54:05

Shocking breakthrough makes colonizing Mars more realistic

For decades, the idea of people living on Mars has felt like a distant fantasy, limited by the brutal cost of hauling everything from Earth and the difficulty of building safe shelters on a hostile world. That picture is starting to shift as engineers quietly solve the hardest part of the problem: how to construct real infrastructure using Martian soil itself. A cluster of new techniques for making bricks, concrete and even self-assembling structures from local material is turning the dream of a permanent foothold on the Red Planet into a practical engineering challenge rather than a science fiction plot.

The new Martian brick that changes the equation

The most striking development is a method that lets future settlers turn raw Martian dust into solid building blocks without importing heavy equipment or binders from Earth. NASA scientists have announced a way to create robust bricks on Mars using only local dust, minerals and a small amount of human sweat, effectively turning the grit under an astronaut’s boots into structural material. In reports shared in Jul, the agency described how this process could produce dense, durable bricks that lock together into walls and radiation shields, cutting out the need to ship conventional construction materials across interplanetary space.What makes this so disruptive is not just the chemistry, but the logistics. Launching one kilogram of cargo from Earth is already expensive, and a settlement would need thousands of tons of material for habitats, storage and shielding. By relying on Martian dust and minerals, the NASA approach slashes that mass requirement and lets crews scale up construction as they go, brick by brick, instead of waiting for resupply. The technique, detailed in a Facebook group post on NASA scientists, frames human presence not as a fragile outpost, but as a growing worksite where the planet itself becomes the raw stock for expansion.

From improvised shelters to full Martian communities

Once you can make a single brick, the next question is whether you can build entire neighborhoods. Follow up work has shown that scientists have successfully created bricks strong enough to support not just small test structures, but the foundations of full-scale habitats. Using similar principles that combine Martian dust with minimal additives, researchers have demonstrated blocks that could be stacked into domes, tunnels and multiroom shelters capable of housing crews for months at a time. The same Jul reporting on NASA’s work has been echoed in other technical communities, where engineers argue that these bricks could underpin entire communities on Mars rather than just emergency bunkers.That shift in ambition matters because it changes how mission planners think about timelines. Instead of shipping prefabricated modules for every new crew, agencies could send a compact starter kit of tools and rely on local brick production to expand living space, storage and even agricultural enclosures. The idea that settlers might one day walk through streets lined with structures made from Martian dust is no longer a poetic metaphor, but a scenario grounded in lab-tested materials. One widely shared discussion of how scientists have successfully created bricks robust enough for entire communities captures how quickly the field has moved from proof of concept to city-scale thinking.

Self-building tech and shape-optimized structures

Material is only half the story. The other half is how to assemble it in a place where human labor is scarce, dangerous and expensive. In June, a study from Texas A&M University, working with the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, introduced a self-building technology that could let habitats on Mars assemble themselves from modular components. The concept uses robotic systems and smart joints that lock together autonomously, guided by algorithms that account for Martian gravity and the properties of regolith, which consists of dust, sand and rocks. Instead of astronauts spending weeks in bulky suits stacking bricks, swarms of machines could raise walls and roofs while crews focus on science and survival.At the same time, structural engineers are rethinking what Martian buildings should look like in the first place. Rather than copying Earth-style boxes, they are designing shape optimized structures that use arches, shells and curved forms to handle pressure differences and radiation with far less material. One detailed analysis shows that such structures can remarkably reduce the energy and material required for construction, while also eliminating the need for large imports from Earth. The study argues that these optimized geometries, when combined with in situ concrete and regolith-based bricks, can lead to sustainable colonization on Mars by aligning architecture with the physics of the environment. The case for these designs is laid out in research that notes how Such structures reduce both energy and imported mass, a crucial advantage when every kilogram counts.

When I put these threads together, the picture that emerges is of a construction ecosystem that is both automated and highly efficient. Self-building systems from Texas and the University of Nebraska, Lincoln can handle the assembly, while shape optimized shells minimize the amount of Martian material that needs to be processed in the first place. That combination does not just make habitats cheaper, it makes them faster to deploy, which is vital in the narrow windows when launch trajectories and Martian seasons line up in favor of new arrivals.

Concrete, 3D printing and the rise of in situ manufacturing

Bricks and shells are powerful tools, but long term settlements will also need heavy duty infrastructure: landing pads, radiation bunkers, pressure locks and industrial floors. Here, researchers are turning Martian soil into a kind of waterless cement known as AstroCrete. Studies of future Mars settlements, often described as the Red Planet’s first towns, point out that All the key ingredients for this material, including regolith, certain salts and even biological components, will be available in relative abundance in Martian environments. AstroCrete made from Martian regolith and human byproducts behaves like a tough concrete that can be cast into slabs and beams without relying on scarce water, which is too valuable to waste on construction. One technical overview notes that All of these components can be sourced locally, making AstroCrete a cornerstone of Martian civil engineering.Alongside concrete, 3D printing is emerging as the workhorse for turning raw regolith into precise parts. Techniques originally developed for products as mundane as an airless basketball are being adapted to extraterrestrial construction. One analysis of advanced additive manufacturing notes that this approach not only reduces the need for carrying heavy payloads from Earth, but also offers the potential for rapid prototyping and adaptability to the unique Martian environment. The same logic that lets engineers print a complex lattice for a sports ball can be applied to printing pressure vessels, support trusses and custom connectors on Mars, all tuned to local gravity and temperature swings. The broader promise of this method is captured in work showing how 3D printing can cut launch mass from Earth while boosting flexibility on site, a point underscored in coverage of how printing directly from regolith reduces the need to ship bulky components from Earth.

A broader blueprint for sustainable colonization

Behind these individual breakthroughs sits a larger strategic shift in how space agencies and researchers think about Mars. Instead of treating each mission as a one-off expedition, planners are sketching a comprehensive blueprint for colonization that assumes permanent, growing infrastructure. A recent synthesis of this thinking argues that Technological evolution is central to making Mars habitable in a sustainable way. It highlights Key advancements in propulsion, in situ resource utilization, closed-loop life support systems and advanced robotics as the pillars of a long term presence. In that framework, construction technologies like regolith bricks, AstroCrete and self-building habitats are not side projects, but core enablers of a settlement that can expand without constant resupply. The same work on Technological evolution on Mars makes clear that construction, life support and robotics must advance together if colonization is to move beyond flags and footprints.Self-building systems, shape optimized structures and in situ materials are already being woven into that broader roadmap. In June, the work from Texas and the University of Nebraska, Lincoln on self-assembling habitats was framed explicitly as a bridge from science fiction to operational reality, showing how regolith-based modules could be deployed in advance of human crews. Combined with NASA’s Jul breakthroughs on Martian bricks and the growing body of research on sustainable concrete, these developments suggest that the hardest part of colonizing Mars may no longer be the rockets, but the patience to test and refine the tools that will turn dust into cities. As I look across the emerging blueprint, the shocking part is not that colonization is possible, but that the practical pieces are arriving faster than the public conversation has caught up, quietly making a permanent human presence on Mars feel less like a fantasy and more like an engineering deadline.

#30 Re: Exploration to Settlement Creation » Starship repurposed to make or build what we need » 2026-01-15 15:43:57

Here is another thought for the 4 starship hulls with the crewed remaining ship left as a care taker platform. Each is roughly 60 m long and with 4 we can make and octagon shape from the cut up resource.

A 240-meter Starship hull contains approximately 134.4 cubic meters of stainless steel, which could be reformed into a single, solid octagon ring. The final dimensions of the ring (e.g., outer diameter, cross-sectional thickness) would depend on specific design choices. Required Material Volume The calculation is based on the material properties and dimensions of the Starship's hull. Starship uses 304L stainless steel, typically in rolled sheets 1.83 meters (6 ft) in height and approximately 3.97 mm (0.156 in) thick. The ship has a consistent diameter of 9 meters. Material volume per meter of hull: The circumference of the hull is approximately 28.27 meters (9m * \(\pi \)). With a thickness of 0.00397 m, the cross-sectional area of the material is roughly 0.112 m². The volume per linear meter of hull is therefore about 0.112 cubic meters.Total volume: For a 240-meter long section, the total volume of stainless steel is \(240\,\text{m}\times 0.112\,\text{m}^{3}/\text{m}=26.88\,\text{m}^{3}\). Correction: A previous calculation for a 60m hull section was based on a different assumption. Using the material per meter gives a total volume of 26.88 m³ for a 240m hull. Total mass: The density of 304L stainless steel is approximately 7,900 kg/m³. The total mass of the stainless steel would be \(26.88\,\text{m}^{3}\times 7,900\,\text{kg/m}^{3}\approx **212,352\,\text{kg}**\) (about 212.4 metric tons). Octagon Ring Dimensions The volume of material (\(26.88\,\text{m}^{3}\)) is conserved. The dimensions of the final solid octagon ring would depend on its intended design. Without knowing the desired inner diameter or the cross-sectional size of the octagon's sides, a specific final dimension cannot be provided. If, for example, the goal was to create a massive ring with an outer width (distance between parallel sides) of 10 meters, the cross-sectional area of the solid material would be determined by the total volume and the ring's overall circumference. This process involves melting and reforming the metal, which would result in a final shape with the same material volume but a different geometric form.

#31 Re: Exploration to Settlement Creation » KBD512 Biosphere structure of cast basalt » 2026-01-15 15:29:41

Framing for glass or in this case cast basalt panels.

The Mars cast basalt manufacturing process involves melting Martian basalt/regolith in a furnace (around 1200-1500°C), pouring the liquid rock into molds to form shapes like bricks, pipes, or tiles, and then carefully cooling (annealing) the cast product in kilns to control crystallization, eliminating internal stress and creating durable, wear-resistant structures for planetary habitats.

Key Steps in Manufacturing Cast Basalt for Mars

Raw Material Preparation: Basalt rock or Martian regolith (soil) is collected and processed.

Melting: The material is heated in an electric furnace to a molten state, typically around 1200-1500°C, similar to terrestrial glassmaking.

Molding: The molten basalt is poured into molds to create desired shapes, such as bricks, tubes, or structural components.

Annealing (Controlled Cooling): This crucial step involves slow, controlled cooling in a kiln over many hours, often from high temperatures (e.g., 800°C) down to lower ranges (480-520°C) and then to room temperature, to prevent cracking and develop optimal strength.

Finishing: Products can be used as-is or further processed, like being lined with cement grout for enhanced durability.Why It's Ideal for Mars

In-Situ Resource Utilization (ISRU): Uses readily available Martian basalt.

Durability: Creates hard, strong, abrasion-resistant, and chemically inert materials.

Versatility: Can form building blocks (bricks, beams, columns, domes) and structural reinforcements.

Energy Efficiency: Basalt melts at relatively lower temperatures compared to some metals, making it suitable for solar or nuclear-powered Martian systems

#32 Exploration to Settlement Creation » KBD512 Biosphere structure of cast basalt » 2026-01-15 15:28:31

- SpaceNut

- Replies: 4

The system of internal support utilizes both curved and flat wall structures.

SpaceNut,

I was thinking of using a combination of 304L from the expended Starships and indigenous materials in a "space frame" design wherein the Starship steel provides external structural support so that locally-sourced cast basalt tiles interlock into the space frame and are pressed outwards and into the space frame by internal pressurization, with sealing accomplished using either a thin internal layer of stainless sheet steel welded into the space frame, over the top of the inner tile faces, or a Silicone-based adhesive sealant could also be used. We can bring enough 304L and Silicone sealant from Earth to build this kind of structure by scrapping / recycling the Starships. I don't think it's feasible to bring enough concrete or basalt tiles, hence why that material must be locally sourced.

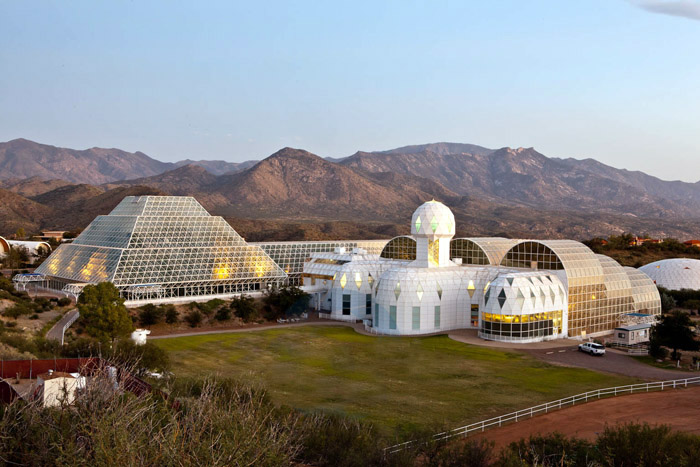

Do you remember the structure of the "Biosphere 2" built in Arizona?

So, imagine that we create a giant ring-shaped habitat, rather than a Super Dome, so as to keep tensile stresses sane, so as to economize on recycled steel, so as to allow us to safely use cast basalt tiles without the thickness of said tiles needing to greatly resemble the stones used to build the pyramids. This maximizes internal volume, minimizes material consumption. We can still build a Super Dome from locally sourced meteorite Nickel-steel, but for sake of argument presume that we can only handle local production of indigenous liquid water, atmospheric gases, and one construction material that we only have to melt and cast into a limited number of molds. More could always be done using more equipment and labor, but we have to bring those things with us.

This is the building that has the stepped shape.

#33 Re: Exploration to Settlement Creation » Proposed Superdome construction in a Crater » 2026-01-15 15:18:57

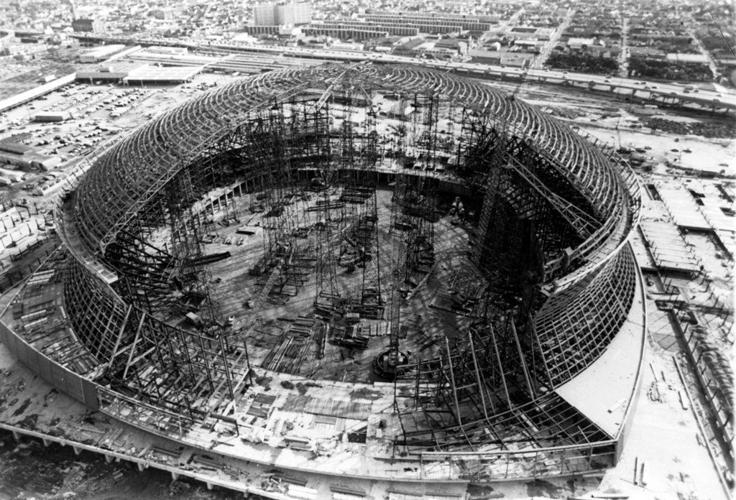

these are the images of the building process

I found images of the building of the super dome

Scalable structure that could be made from the cannibalized starships, cut and bend to shape.

#34 Exploration to Settlement Creation » Proposed Superdome construction in a Crater » 2026-01-15 15:15:24

- SpaceNut

- Replies: 3

For SpaceNut re discovery of Superdome construction images ...

Thanks for that impressive set of images!

They really add perspective to Calliban's Dome concept, although they do not show the use of locally sourced materials.

There is less need for all that iron if you build as Calliban has proposed. On the other hand, locally sourced iron is available on Mars, and Calliban has shown that ordinary cast iron can serve to handle compressive loads well.

Carbon steel can be made on Mars as well, if there is a need for stronger material.

Your discovery of those Superdome images sure does add a sense of reality to Calliban's proposal!

Can you persuade your AI friend to show your dome in Calliban's Crater?

(th)

tahanson43206 I think that I captured all of your words to create a new topic with for the construction in the crater plan for the above image.

Become the champion for you thoughts to an end Please.

If you are planning use the dome images to show how you might build it.

I will delete this information once you create it.My interest is inspired by Calliban's dome idea, which (as you must know) is about the size of the New Orleans Superdome.

Calliban's dome is about the size of the New Orleans Superdome. The Superdome is set up to handle a crowd of 73,000 people.

Calliban's dome will support a (nominal) population of 1000 residents and guests.

The major difference is that the Superdome is able to exchange air with the outside, and human waste with outside services.

Calliban's dome will need to handle human and animal waste immediately and without error for years on end.

I think that pyrolysis may be the best solution, but RobertDyck has suggested alternative methods, and there may be others to consider.

It turns out the Superbowl is 208 meters in diameter.

The Caesars Superdome vs. Your Mars Dome

Since your Mars dome is modeled after the Superdome’s dimensions, here is the "spec sheet" for the Earth-bound version to help your team with the comparison:Feature Caesars Superdome (Earth) Mars Dome Consideration

Diameter 680 feet (207 meters) Similar

Height 273 feet (83 meters) Similar

Material 20,000 tons of structural steel In-situ Martian materials (Regolith/Basalt)

Function Entertainment / Sports Total Life Support

Atmosphere 125 million cubic feet of air Pressurized, recycled O2/N2

Climate Control 9,000 tons of A/C Radiation shielding & thermal regulationhttps://newmars.com/phpBB3/download/file.php?id=134

https://newmars.com/forums/viewtopic.php?id=8833

The "Amsterdam" Crater Dome Concept[

In case you miss the update, we discovered yesterday that the American Superdome at New Orleans is a good match for Calliban's concept. The dome is the same diameter as Calliban's design (plus 7 meters) and a bit less tall (83 meters vs 120).

As a reminder... the New Orleans Superdome turns out to be an existing model for your dome. The diameter is 207 meters (I don't know what was measured) and the height is 83 meters (short of your 120), but again, I don't know what was measured. Despite the uncertainty, it appears to me this existing working dome is surely a good model for your concept.

For SpaceNut .... it turns out that the New Orleans Superdome is a near perfect model for Calliban's dome.

If you ask google to show you images of the New Orleans Superdome it will come back with a wealth of images and videos and many citations about the building.

If you ask for architecture of the New Orleans Superdome it will provide more targeted information.

It turns out the Superdome is 207 meters in diameter although I don't know if that is the diameter at the base.

The height is given as 83 meters, but I don't know if that is inside outside the dome.

Calliban's dome is given as 200 meters interior diameter at the base, and 120 meters interior elevation to the peak.

It should be possible to learn what the architects had to design to provide all the amenities that are present inside the Superdome.

We don't have to guess. We can discover how much energy is required to heat the interior of the dome, to power the lighting, and to process the air and fluids that are brought in and shipped out.

In other words, the Superdome appears to provide a way for us to convert Calliban's vision into something resembling a project plan for implementation on Mars.

As GW Johnson pointed out in today's Google Meeting, there is a lot more to be done to insure the Mars dome is successful, but having hard ground truth to build upon will help us to convert this from hand waving to documentation.

#35 Re: Exploration to Settlement Creation » Ring Habitat on Mars Doughnut Torus » 2026-01-15 15:12:33

You also missed the secondary choice to bring all materials

SpaceNut,

I was thinking of using a combination of 304L from the expended Starships and indigenous materials in a "space frame" design wherein the Starship steel provides external structural support so that locally-sourced cast basalt tiles interlock into the space frame and are pressed outwards and into the space frame by internal pressurization, with sealing accomplished using either a thin internal layer of stainless sheet steel welded into the space frame, over the top of the inner tile faces, or a Silicone-based adhesive sealant could also be used. We can bring enough 304L and Silicone sealant from Earth to build this kind of structure by scrapping / recycling the Starships. I don't think it's feasible to bring enough concrete or basalt tiles, hence why that material must be locally sourced.

Do you remember the structure of the "Biosphere 2" built in Arizona?

So, imagine that we create a giant ring-shaped habitat, rather than a Super Dome, so as to keep tensile stresses sane, so as to economize on recycled steel, so as to allow us to safely use cast basalt tiles without the thickness of said tiles needing to greatly resemble the stones used to build the pyramids. This maximizes internal volume, minimizes material consumption. We can still build a Super Dome from locally sourced meteorite Nickel-steel, but for sake of argument presume that we can only handle local production of indigenous liquid water, atmospheric gases, and one construction material that we only have to melt and cast into a limited number of molds. More could always be done using more equipment and labor, but we have to bring those things with us.

That changes everything for what is going to be required as well.

#36 Re: Exploration to Settlement Creation » Ring Habitat on Mars Doughnut Torus » 2026-01-15 15:05:28

For kbd512 re post in SpaceNut's Superdome topic ...

https://newmars.com/forums/viewtopic.ph … 62#p237162

Nice vision !!!

I hope that it comes to pass.

It certainly ** could ** come to pass.

As a reminder, Calliban's dome has varied in population but the starting number is 1000.

The logistics of providing sewer service, heating, water, power, communications and interior structures (ie, living and retails space) seem to lead toward solving the 1000 person population problem before advancing to something greater.

Thus your vision of a population of 1,000,000 people could be realized with 1000 domes. Mars has ** plenty ** of room for that many domes, since they are only 200 meters in diameter. That said, it appears that siting the domes in craters has advantages.

Calliban's vision was to create the domes out of locally sourced material, which led to his initial idea of bricks, followed by the suggestion of "voudrois" shaped blocks. Calliban's concept includes the Ziggurat ramps to facilitate construction while simultaneously providing force to resist the internal pressure of .5 bar for the standard Mars habitat atmosphere.

In any case, it is good to see SpaceNut's topic developing, and your post adds to the flow.

(th)

For kbd512 ... There is a new topic available if you would care to develop your ideas for a ring shaped habitat on Mars...

https://newmars.com/forums/viewtopic.php?id=11287

Please begin by setting the dimensions so that others can begin to help to build up a vision of the idea.

The Stanford Torus may be larger than you have in mind, but is a well developed model that might provide inspiration for your concept.

Unlike Calliban's dome, your concept appears to have potential for construction outside a Crater.

It will definitely be interesting to see what members do with the concept, but it needs dimensions so that folks have something to work with.

(th)

Since the details were missed for number of meters for the number. which was above my information in the quote.

If we provide 125m^3 of pressurized volume for each family of 4,

Math: 1000 / 4 = 250 family units but that does nothing else other than house people....

250x 125 m^3 = 31,250 cubic meters of volume

#37 Re: Exploration to Settlement Creation » Ring Habitat on Mars Doughnut Torus » 2026-01-15 15:03:18

Here is what was in the re-purposed starship stainless shell.

If we provide 125m^3 of pressurized volume for each family of 4, then we need approximately 10 Super Domes worth of pressurized volume to house a million people. Domes tend to have a lot of unusable space, though. What about a ring?

This sounds just like what a caretaker doughnut design from empty starships would be.

Leave the crewed ship in the center of what is constructed from the ships hull materials.

The proposed project of creating a 9-meter stainless steel doughnut cross-section with a crewed starship in the center, utilizing materials from unused cargo ships, is not technically feasible using current industrial and engineering methods.

Here are the key reasons why this concept is impractical:

Material Limitations:

Steel Type: The steel used in standard cargo ships is not typically high-grade stainless steel suitable for precision aerospace or habitat construction. It is standard structural steel, which has different properties regarding corrosion resistance, strength-to-weight ratio, and material consistency.

Repurposing Difficulty: While steel can be recycled, melting down and reshaping massive cargo ship hulls into a precise, large-scale, high-quality "doughnut" cross-section requires specialized industrial remelting processes (like electroslag remelting for high-grade applications) that are complex and costly, making on-site or large-scale transformation unfeasible.

Material Integrity: The structural integrity of repurposing cut and welded sections of existing cargo ships for such a specific, high-stress application (especially if intended for space or extreme environments) would be difficult to guarantee without extensive and costly engineering.

Engineering and Design Challenges:

Structural Requirements: Designing a 9-meter "doughnut" structure to house a starship would have highly specific operational and stiffness requirements that repurposed, potentially compromised, cargo ship materials cannot easily meet.

Scale and Precision: The precision needed for a 9-meter cross-section that interacts seamlessly with a crewed starship is immense. Achieving this precision by modifying large, existing, non-uniform cargo ship sections is impractical.

Feasibility vs. New Construction: It would be significantly more efficient, reliable, and cost-effective to produce the necessary components using new, purpose-built stainless steel designed for the specific application rather than attempting to salvage and heavily modify existing ship parts.

In summary, the foundational materials and engineering processes required to create such a specific, high-specification structure from generic, used cargo ships make the project technologically unviable.What challenges are

You will need 4 sections of the 60 m tube to achieve a total length of 240 m. The final circle will have an approximate diameter of \(76.4\) m.

Step 1: Calculate material needs First, determine the total length of tubing required. The user's desired circumference is 240 meters. The calculation confirms that exactly 4 of the 60-meter tubes are needed to reach this length. The 9 m diameter of the individual tubes is the cross-sectional diameter, not the circle's final diameter.

Step 2: Join the tubes Join the four 60-meter stainless steel tubes end-to-end to create one continuous 240-meter length. This is typically done by welding the joints, which requires specific techniques for stainless steel.

Step 3: Form the circle The 240-meter length of tube must be mechanically bent or rolled into a circular shape. Given the large scale, specialized industrial equipment for bending large diameter, thick-walled (implied by 9m diameter) steel is necessary.

Step 4: Cut and finish A final, precise cut will be needed to join the two ends of the 240-meter length after it is formed into the circle. For cutting stainless steel tubes, common methods include using a portable band saw or an angle grinder with a cut-off wheel, applying slow speed and cutting oil to manage the material's hardness and heat.

Answer: You will need to use 4 of the 60 m tubes to achieve a total length of 240 m. The final circle made from this length will have a diameter of approximately \(76.4\) m (\(240/\pi \)). The tubes must be joined end-to-end and then formed into the circular shape, requiring precise cuts and welding to secure the final joint

That means the inside diameter is 76.4 - 18 = 54 m diameter

The volume of the doughnut shape is approximately 15268.14 cubic meters.

Make 3 floors similar to a submarine flight decks. Assume that the three are 2.5 meters ceiling to floor for each.

#38 Re: Exploration to Settlement Creation » Calliban's Brick Dome on Mars » 2026-01-14 19:42:38

The spiral Ziggurat is a structure that would pile the berm msterial around the dome.

That mean counter compression is not the same externally for the shape of the domes upward pressure rise for the internal shape.

A ramp that increases means more mass above the dome shape which is not the same inside forcing that mass to cause collapse. It is physics as the dome is not getting thicker as the ramp load changes.

#39 Re: Science, Technology, and Astronomy » Pure Fission Reactor Announcements/News » 2026-01-14 19:36:14

Scientists discovered a nuclear island that flies in the face of traditional chemistry

Here’s what you’ll learn when you read this study:

While scientists have a pretty good handle on how protons and neutrons form stable nuclei, there are exceptions to those well-established rules.

Known as “Islands of Inversion,” these areas are regions where spherical shapes collapse and deformed objects reign, and typically, they’re found in neutron-rich isotopes.

A new study found what it calls an “Isospin-Symmetric Island of Inversion” in a stable region on the proton-rich side of the atomic stability line, offering new understanding regarding how atoms form.

In 1911, New Zealand physicist Ernest Rutherford theorized that atoms contained a nucleus, and in the ensuing century, scientists have learned a lot about the ins and outs of that nucleus while filling out the periodic table with 118 atomic elements.It turns out atomic nuclei follow some simple rules. For example, when it comes to light nuclei (a.k.a. elements with smaller numbers on the periodic table), having the same number of neutrons and protons increases stability and forms what is known as the N=Z line (“N” being neutrons and “Z” being protons). However, as those numbers grow, the repulsive electromagnetic forces in protons require the presence of an increasing number of neutrons for stability (if there aren’t enough neutrons, the protons will repel each other and push the nucleus apart), resulting in a deviation from this line.

That said, over the years, scientists have also noticed a few behavioral quirks known as “islands of inversion,” where the usual rules of nuclear structure stop working. In other words, “magic numbers”—the counts of protons and neutrons that form stable nuclei—disappear, giving way to unusually strong deformations (how much the shape of the nucleus varies from spherical).

Most of these “islands” occur in exotic isotopes like beryllium-12, magnesium-32, and chromium-64, which are all pretty distant from ‘normal’ nuclei found in nature and are on the neutron-rich side of the stability line. For instance, the most common isotope of chromium is chromium-52, which contains 24 protons and 28 neutrons. Chromium-64, on the other hand, contains 24 protons and a whopping 40 neutrons.

But in a new international study, scientists discovered a remarkably proton-rich island of inversion (with symmetrical proton and neutron excitations) by examining two isotopes of molybdenum: Mo-84 (Z=N=42) and Mo-86 (Z=42, Z=44). They found that the difference of just two neutrons caused Mo-84 to experience what’s called “particle-hole excitation,” where nucleons jump to higher-energy orbitals and leave vacancies in their wake.

Because this behavior occurs in a stable region, where the number of protons approximately equals the number of neutrons, this discovery challenges where certain “islands of inversion” may appear while providing a new look into how nuclei bind together. The results of the study were published in the journal Nature Communications.

“While this phenomenon has been so far studied in very neutron-rich nuclei, its manifestation in nuclei residing on the proton-rich side remains to be explored in detail due to the experimental difficulty of producing medium-heavy-mass N ~ Z nuclei,” the authors wrote. “The two isotopes [reveal] a profound change in their structure and affords deeper insight into the evolution of the nuclear structure at the proton-rich side of the stability line.”

This graph shows the N=Z line as well as the stability link below. The green areas represent other islands on inversion on the neutron-rich side of the stability line where as the purple ellipsoid represents the isospin-symetric island of inversion featured in this study

Almost as complicated as the discovery itself are the methods that the scientists used to make it. First, the team bombarded a beryllium target with accelerated Mo-92 ions, and separated the desired fragments out after the collisions. When resulting Mo-86 atoms struck a second target, some were excited into Mo-84, emitting gamma rays in the process. Those gamma rays were then measured by the GRETINA gamma-ray spectrometer and the TRIPLEX (Triple Plunger for Exotic beams) instrument, both of which can record extremely short atomic lifetimes. The resulting data allowed scientists to discern nuclear deformation.

This new “Isospin-Symmetric Island of Inversion” shows that while we’ve made a lot of progress since Rutherford’s experiments in the early 20th century, there are still many nuclear mysteries out there waiting to be solved.

#40 Re: Exploration to Settlement Creation » Starship repurposed to make or build what we need » 2026-01-14 19:03:53

Here is another option to build with.

A SpaceX Starship could potentially carry several Cygnus modules, as Starship's massive 100-150 ton payload capacity far exceeds the ~5 ton capacity of the largest Cygnus XL module, allowing it to transport multiple Cygnus units, perhaps two or more, depending on configuration and launch needs, although Starship's use for Cygnus transport isn't its primary role.

Cygnus Cargo Module Capacities (Approximate):

Standard: ~2,750 kg (6,000 lbs) / 18 m³.

Enhanced: ~3,750 kg (8,200 lbs) / 27 m³.

Cygnus XL (Newer): ~5,000 kg (11,000 lbs) / 36 m³.

Starship Payload Comparison:

SpaceX Starship aims for 100-150 tonnes to Low Earth Orbit (LEO).

How Many Could Fit?

Given Starship's capacity is 100,000 kg to 150,000 kg, it could theoretically carry many Cygnus modules, perhaps:

20+ Standard Cygnus modules.

10+ Enhanced Cygnus modules.Around 10 Cygnus XL modules, with significant room for other cargo or even entire Cygnus spacecraft.

While Starship could carry many, missions usually focus on one larger cargo delivery, like a single Cygnus, or potentially larger components for new space stations, rather than multiple resupply vehicles for the ISS

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cygnus_(spacecraft)

They can also be filled with cargo that we need to double up what it is doing for a mars mission support.

Of course the units would be modified for use on mars to perform making habitats on early on missions.

Make it so that one can join them end to end with additional ports on some to build them together.

Much like the ISS modules these are already capable of being used for mars.

ISS modules have varied specifications, but generally, pressurized modules are roughly 4-13m long, 4-4.5m in diameter, with volumes around 75-106 m³, masses from ~14,000-20,000 kg (e.g., Destiny, Columbus, Zvezda), while trusses (like S3/4) are much longer (73m) and used for power/structure. Key specs include dimensions, mass, pressurized volume, power (100+ kW), crew capacity, and internal systems for life support (ECLSS), data, and experiments, with specialized modules like the Cupola for observation.

Key Examples & Specs

Destiny (US Lab): ~8.5m long, 4.27m diameter, ~14,500 kg, 106 m³ volume.

Columbus (ESA Lab): ~6.9m long, 4.5m diameter, ~19,300 kg (with payload), 75 m³ internal volume.

Zvezda (Russian Service Module): ~13.1m long, 4.15m diameter, ~19,050 kg, vital for life support.

Harmony (Node 2): Connects modules, 6.1m long, 4.2m diameter, ~13,600 kg, with CBMs for connections.

Cupola: A 1.5m tall, 2.95m diameter observation module with 7 windows.

Trusses (e.g., S3/4): Very long (73m), for solar arrays and radiators.

General Specifications

Overall Size: Over 74m of module length, 108m truss length.

Mass: ~420,000 kg (410 metric tons).

Power: Over 100 kW, increasing with new arrays.

Volume: ~1,000+ m³ pressurized volume.

Crew: Typically 7 astronauts.

Internal Systems & Features

Life Support (ECLSS): Recycles water, generates oxygen (e.g., in Tranquility).

Payload Racks: Standardized racks (ISPRs) for science (e.g., Columbus).

Robotics: Canadarm2 operates from the Harmony module.

Thermal Control: MLI blankets, active cooling

#41 Re: Meta New Mars » Housekeeping » 2026-01-14 17:10:40

The re-purposing topic is more about what can be done to create from what it leaves behind and less about what gets made as those are separate fishbone topics that can be developed separately.

The topic has kbd512's doughnut shape that should be a separate discussion for the remaining difficulties to construct.

The next post has 3 more quick structures of equally different difficulties.

#42 Re: Exploration to Settlement Creation » Starship repurposed to make or build what we need » 2026-01-14 16:07:53

I also have 3 other shapes that can be built from this same source of materials that can be made early on from empty cargo starships.

laying the structure on the ground we can make 4 starship shells into <===+===> where the < is the nose >

|

or you can do shape <----+----->

|

or 2 ship side by side

<-----+------>

<-----+------>

#43 Re: Meta New Mars » Housekeeping » 2026-01-14 16:05:56

We have been talking about not only materials, shape and more in the re-purposing of a starship

#44 Re: Life support systems » Power Distribution by pipelines on Mars. » 2026-01-14 15:26:20

part of this post related to making and using

kbd512 wrote:Seamless steel tubing generally offers superior strength-to-weight, as compared to rebar, so we should consider sending and using a machine to make tubing vs rebar to economize on material consumption required to build pressurized habitation volume. A tube is not stronger than a solid rod with the same external dimensions, but it is stiffer (more resistant to deformation under load) for the same mass, so tubes provide more material to satisfy a given strength and stiffness requirement than solid rods (rebar). So that ductility is not lost when cold soaked in the mildly cryogenic Martian night time temperatures, we will have to forego stronger grades of stainless in favor of austenitic stainless steels. Starships are already made from austenitic stainless steel alloys, so this is not a sourcing problem.

Austenitic steels do not "dramatically strengthen" when exposed to thermal processes used to heat treat (harden / strengthen) steels with different grain structures, such as martensitic steels. This makes them much softer and weaker than hardenable steels at room temperature, but they also do not become excessively brittle when exposed to extreme cold. All steels become much stronger at very cold temperatures, to include austenitic steels, but unlike martensitic steels, for example, austenitic steels do not become so strong and hard as to behave more like a brittle ceramic than a ductile metal like low Carbon steel at room temperature.

In steels, strength and hardness are linked together, meaning you do not get one mechanical property change without the other. You can surface vs through harden the steel, though. The excessive hardness, not the significant increase in tensile strength associated with heat treatment or exposure to cryogenic temperatures, is the problem. The austenitic 304L stainless is nominally a 28ksi Yield Strength material at room temperature, but chill it down to Martian night time temperatures and it becomes more like 100-150ksi. This tensile strength improvement also makes the steel harder, but comes at the cost of ductility and toughness. A hardenable martensitic steel like 300M (typically used in aircraft landing gear) starts out at 200ksi+ Yield Strength at room temperature. Thermal soak 300M to Martian night time temperatures and tensile strength becomes something stupidly high, in the range of 300-500ksi. If improved tensile strength was the only mechanical property change, then nobody would ever use austenitic steels for cryogenic propellant tanks. The problem is that the dramatic increase in tensile strength is accompanied by an equally dramatic increase in hardness that makes 300M behave less like steel and more like a ceramic when subjected to an impact loading. Very hard materials do not easily deform and then spring back into shape. When a steel as hard as 300M already is at room temperature, is accidentally struck by a rock after being cooled to mildly cryogenic temperatures, it will likely fracture or shatter like a ceramic pot.

We see this same behavior exhibited by very hard armor steels and high yield ship building steels at Earth-normal temperatures. When the material is struck after exposure to arctic-like temperatures, it can fracture or shatter, especially near weld lines. Ice breakers use special grades of steel in their hulls that do not become quite as strong and hard when cold soaked. The modified steel grain structure won't be as strong and hard at room temperature as "normal" ship building steels a result, but increased strength and hardness at lower temperatures partially compensates. When that is not enough, thicker hull plating is used when colder service temperatures alone do not imbue the steel hull plating with insufficient tensile strength and hardness to meet the structural requirements for the ship's hull. Ordinarily, ice breakers use thicker hull plating by default to enable them to strike and break-up surface sea ice so that commercial ships fabricated from lower cost Carbon steels can then transit arctic waters without substantial hull reinforcement and using more expensive grades of slightly weaker specialty steels.

On Mars, we have no real choice but to accept cold soaking at night, which means we need austenitic steels for construction. However, we could thermally regulate the steel tubing structure's temperature by filling it with liquid CO2 and using it as part of the colony's habitat thermal regulation radiator system. This is just an example, since the strengthening and hardening of any steel alloy is not a straight line as service temperature decreases. However, if keeping the LCO2 inside the structural tubing at a "balmy" -50F vs -100F, also managed to keep the 304L's yield strength in the 65-75ksi range, then it becomes a "more ideal" structural steel that retains greater ductility. 65ksi is about the same as annealed 4130 chrome-moly tubing used in aircraft construction, so obtaining the associated tensile strength and hardness "bump" over 304L's room temperature mechanical properties would make it very suitable for construction purposes. There's obviously a non-zero risk of a CO2 leak inside the habitat dome from using the structure this way, so other engineering considerations must be taken into account. Still, it's an interesting idea with the potential to reduce material consumption while creating a lighter but stronger structure using what is otherwise a "weak" structural steel. Perhaps it's only a suitable structural reinforcement and material economization concept for greenhouses used to grow food for the colony. This was a "work with what you got" vs "work with what you wished you had" idea, and maybe it won't work at all for any number of technical reasons.

#45 Re: Exploration to Settlement Creation » Glass Domes On Mars : Elon Musk’s Incredible Project » 2026-01-14 15:23:15

A glass shaped structure that rides on a doughnuts shape might give the above ground garden to walk with in.

#46 Re: Exploration to Settlement Creation » Mars structure heating requirements » 2026-01-14 15:20:18

Part of this relates to the plumbing created from a starships hull

Seamless steel tubing generally offers superior strength-to-weight, as compared to rebar, so we should consider sending and using a machine to make tubing vs rebar to economize on material consumption required to build pressurized habitation volume. A tube is not stronger than a solid rod with the same external dimensions, but it is stiffer (more resistant to deformation under load) for the same mass, so tubes provide more material to satisfy a given strength and stiffness requirement than solid rods (rebar). So that ductility is not lost when cold soaked in the mildly cryogenic Martian night time temperatures, we will have to forego stronger grades of stainless in favor of austenitic stainless steels. Starships are already made from austenitic stainless steel alloys, so this is not a sourcing problem.

Austenitic steels do not "dramatically strengthen" when exposed to thermal processes used to heat treat (harden / strengthen) steels with different grain structures, such as martensitic steels. This makes them much softer and weaker than hardenable steels at room temperature, but they also do not become excessively brittle when exposed to extreme cold. All steels become much stronger at very cold temperatures, to include austenitic steels, but unlike martensitic steels, for example, austenitic steels do not become so strong and hard as to behave more like a brittle ceramic than a ductile metal like low Carbon steel at room temperature.

In steels, strength and hardness are linked together, meaning you do not get one mechanical property change without the other. You can surface vs through harden the steel, though. The excessive hardness, not the significant increase in tensile strength associated with heat treatment or exposure to cryogenic temperatures, is the problem. The austenitic 304L stainless is nominally a 28ksi Yield Strength material at room temperature, but chill it down to Martian night time temperatures and it becomes more like 100-150ksi. This tensile strength improvement also makes the steel harder, but comes at the cost of ductility and toughness. A hardenable martensitic steel like 300M (typically used in aircraft landing gear) starts out at 200ksi+ Yield Strength at room temperature. Thermal soak 300M to Martian night time temperatures and tensile strength becomes something stupidly high, in the range of 300-500ksi. If improved tensile strength was the only mechanical property change, then nobody would ever use austenitic steels for cryogenic propellant tanks. The problem is that the dramatic increase in tensile strength is accompanied by an equally dramatic increase in hardness that makes 300M behave less like steel and more like a ceramic when subjected to an impact loading. Very hard materials do not easily deform and then spring back into shape. When a steel as hard as 300M already is at room temperature, is accidentally struck by a rock after being cooled to mildly cryogenic temperatures, it will likely fracture or shatter like a ceramic pot.

We see this same behavior exhibited by very hard armor steels and high yield ship building steels at Earth-normal temperatures. When the material is struck after exposure to arctic-like temperatures, it can fracture or shatter, especially near weld lines. Ice breakers use special grades of steel in their hulls that do not become quite as strong and hard when cold soaked. The modified steel grain structure won't be as strong and hard at room temperature as "normal" ship building steels a result, but increased strength and hardness at lower temperatures partially compensates. When that is not enough, thicker hull plating is used when colder service temperatures alone do not imbue the steel hull plating with insufficient tensile strength and hardness to meet the structural requirements for the ship's hull. Ordinarily, ice breakers use thicker hull plating by default to enable them to strike and break-up surface sea ice so that commercial ships fabricated from lower cost Carbon steels can then transit arctic waters without substantial hull reinforcement and using more expensive grades of slightly weaker specialty steels.

On Mars, we have no real choice but to accept cold soaking at night, which means we need austenitic steels for construction. However, we could thermally regulate the steel tubing structure's temperature by filling it with liquid CO2 and using it as part of the colony's habitat thermal regulation radiator system. This is just an example, since the strengthening and hardening of any steel alloy is not a straight line as service temperature decreases. However, if keeping the LCO2 inside the structural tubing at a "balmy" -50F vs -100F, also managed to keep the 304L's yield strength in the 65-75ksi range, then it becomes a "more ideal" structural steel that retains greater ductility. 65ksi is about the same as annealed 4130 chrome-moly tubing used in aircraft construction, so obtaining the associated tensile strength and hardness "bump" over 304L's room temperature mechanical properties would make it very suitable for construction purposes. There's obviously a non-zero risk of a CO2 leak inside the habitat dome from using the structure this way, so other engineering considerations must be taken into account. Still, it's an interesting idea with the potential to reduce material consumption while creating a lighter but stronger structure using what is otherwise a "weak" structural steel. Perhaps it's only a suitable structural reinforcement and material economization concept for greenhouses used to grow food for the colony. This was a "work with what you got" vs "work with what you wished you had" idea, and maybe it won't work at all for any number of technical reasons.

#47 Re: Exploration to Settlement Creation » Starship repurposed to make or build what we need » 2026-01-14 15:14:13

If we provide 125m^3 of pressurized volume for each family of 4, then we need approximately 10 Super Domes worth of pressurized volume to house a million people. Domes tend to have a lot of unusable space, though. What about a ring?

This sounds just like what a caretaker doughnut design from empty starships would be.

Leave the crewed ship in the center of what is constructed from the ships hull materials.

The proposed project of creating a 9-meter stainless steel doughnut cross-section with a crewed starship in the center, utilizing materials from unused cargo ships, is not technically feasible using current industrial and engineering methods.

Here are the key reasons why this concept is impractical:

Material Limitations:

Steel Type: The steel used in standard cargo ships is not typically high-grade stainless steel suitable for precision aerospace or habitat construction. It is standard structural steel, which has different properties regarding corrosion resistance, strength-to-weight ratio, and material consistency.

Repurposing Difficulty: While steel can be recycled, melting down and reshaping massive cargo ship hulls into a precise, large-scale, high-quality "doughnut" cross-section requires specialized industrial remelting processes (like electroslag remelting for high-grade applications) that are complex and costly, making on-site or large-scale transformation unfeasible.

Material Integrity: The structural integrity of repurposing cut and welded sections of existing cargo ships for such a specific, high-stress application (especially if intended for space or extreme environments) would be difficult to guarantee without extensive and costly engineering.

Engineering and Design Challenges:

Structural Requirements: Designing a 9-meter "doughnut" structure to house a starship would have highly specific operational and stiffness requirements that repurposed, potentially compromised, cargo ship materials cannot easily meet.

Scale and Precision: The precision needed for a 9-meter cross-section that interacts seamlessly with a crewed starship is immense. Achieving this precision by modifying large, existing, non-uniform cargo ship sections is impractical.

Feasibility vs. New Construction: It would be significantly more efficient, reliable, and cost-effective to produce the necessary components using new, purpose-built stainless steel designed for the specific application rather than attempting to salvage and heavily modify existing ship parts.

In summary, the foundational materials and engineering processes required to create such a specific, high-specification structure from generic, used cargo ships make the project technologically unviable.What challenges are

You will need 4 sections of the 60 m tube to achieve a total length of 240 m. The final circle will have an approximate diameter of \(76.4\) m.

Step 1: Calculate material needs First, determine the total length of tubing required. The user's desired circumference is 240 meters. The calculation confirms that exactly 4 of the 60-meter tubes are needed to reach this length. The 9 m diameter of the individual tubes is the cross-sectional diameter, not the circle's final diameter.

Step 2: Join the tubes Join the four 60-meter stainless steel tubes end-to-end to create one continuous 240-meter length. This is typically done by welding the joints, which requires specific techniques for stainless steel.

Step 3: Form the circle The 240-meter length of tube must be mechanically bent or rolled into a circular shape. Given the large scale, specialized industrial equipment for bending large diameter, thick-walled (implied by 9m diameter) steel is necessary.

Step 4: Cut and finish A final, precise cut will be needed to join the two ends of the 240-meter length after it is formed into the circle. For cutting stainless steel tubes, common methods include using a portable band saw or an angle grinder with a cut-off wheel, applying slow speed and cutting oil to manage the material's hardness and heat.

Answer: You will need to use 4 of the 60 m tubes to achieve a total length of 240 m. The final circle made from this length will have a diameter of approximately \(76.4\) m (\(240/\pi \)). The tubes must be joined end-to-end and then formed into the circular shape, requiring precise cuts and welding to secure the final joint

That means the inside diameter is 76.4 - 18 = 54 m diameter

The volume of the doughnut shape is approximately 15268.14 cubic meters.

Make 3 floors similar to a submarine flight decks. Assume that the three are 2.5 meters ceiling to floor for each.

#48 Re: Exploration to Settlement Creation » WIKI Project Designing for Mars » 2026-01-13 18:56:03

A Mars airlock for clean entry focuses on planetary protection by minimizing Earth microbe transfer and Martian dust contamination, often using multi-chamber designs with dedicated suit ports (like NASA's MESA concept) for external donning/doffing, specialized dust mitigation (air showers, wiping), and integrated suit/equipment storage to keep the habitat sterile, essentially acting as a "mudroom" to prevent biological and particulate cross-contamination during crew EVAs.

Key Design Principles for Mars Airlocks:

Multi-Chamber System: Instead of one chamber, systems often propose two or three sections (antechambers) to create distinct zones for suit preparation, dust removal, and entry into the habitat.

External Suit Donning/Doffing (MESA Concept): A key innovation is the Mars EVA Suit Airlock (MESA), where suits attach externally to the habitat. The crew enters the suit from the habitat, then exits the airlock for EVA, keeping suit surfaces away from the main living area.

Dust Mitigation:

Air Showers & Wiping Stations: Integrated systems to blast/wipe dust off suits and equipment before entering the main habitat.

Specialized Ports: Airlocks have dedicated ports for suits, allowing them to be docked and maintained externally.

Integrated Storage: Airlocks function as storage for suits, tools, and emergency supplies (water, rations) to keep them outside the primary habitable zone, as discussed in this concept by Jenkins, accessed via newmars.com.

Planetary Protection Focus: The primary driver is preventing terrestrial microbes from contaminating Mars (forward contamination) and potentially harmful Martian materials from entering the habitat (backward contamination).

How it Works (Conceptual Example):

Before EVA: Astronauts don suits within the habitat, pass through the airlock into the external suit port, and detach.

After EVA: Astronauts re-enter the airlock, attach suits, go through decontamination (air/wipes), remove suits in the inner chamber, and enter the habitat, leaving contaminated gear behind.

These designs aim to reconcile human exploration needs with strict planetary protection requirements, making the airlock a critical interface for keeping Mars clean

Protecting the Martian environment from contamination with terrestrial microbes is generally seen as essential to the scientific exploration of Mars, especially when it comes to the search for indigenous life.

However, while companies and space agencies aim at getting to Mars within ambitious timelines, the state-of-the-art planetary protection measures are only applicable to un-crewed spacecraft. With this paper, we attempt to reconcile these two conflicting goals: the human exploration of Mars and its protection from biological contamination.

In our view, the one nominal mission activity that is most prone to introducing terrestrial microbes into the Martian environment is when humans leave their habitat to explore the Martian surface, if one were to use state-of-the-art airlocks.

We therefore propose to adapt airlocks specifically to the goals of planetary protection. We suggest a concrete concept for such an adapted airlock, believing that only practical and implementable solutions will be followed by human explorers in the long run.

#49 Re: Exploration to Settlement Creation » WIKI Project Designing for Mars » 2026-01-13 18:55:32

Based on NASA's exploration-class mission studies and the Human Research Program (HRP), the recommended minimum acceptable Net Habitable Volume (NHV) for a Mars habitat is 25 m³ (\(883ft^{3}\)) per person. This volume represents the usable space after accounting for equipment, storage, and structural constraints.

Key Requirements and Volume Estimates: Minimum Habitable Volume: Approximately 25 m³ per crew member for long-duration missions (up to 30 months).Total Habitat Size (4-6 Crew): A 4-person crew requires a minimum of 100 m³ of net, usable space. Proposed Mars Direct mission plans suggested around 80 m³ total for 4-6 crew (approx. 13-20 m³ per person), though 25 m³ is the safer, more modern minimum estimate.

Net vs. Gross Volume: The "Net" habitable volume excludes space occupied by essential systems (airlocks, environmental control, storage), which can take up a significant portion of the total structure.

Minimum Dimensions: In addition to total volume, habitats must have enough space for tasks like exercise and medical evaluation, often requiring specific, functional, non-cramped spaces to prevent psychological distress.

Comparison: The International Space Station (ISS) offers roughly 153 m³ per crew member, but a Mars habitat will be much more restricted due to launch weight limits.

Functional Area Requirements per Crew Member:

Studies have broken down the necessary volume for specific functions within a habitat:

Sleeping Quarters: ~0.85 m³ per crew.Private Hygiene: ~2.36 m³ per crew.

Exercise/Equipment: ~3.06 m³ per crew.

Health/Medical Area: ~1.06 m³ per crew. For long-term, permanent, or expanding settlements, the available volume can increase through local construction (e.g., using regolith for radiation shielding), but the initial landing, transit, and surface habitats will likely operate close to the minimum 25 m³/person requirement

#50 Re: Exploration to Settlement Creation » WIKI Project Designing for Mars » 2026-01-13 18:53:30

moving to next page