New Mars Forums

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

Announcement

#1 2016-03-07 10:22:56

- RobertDyck

- Moderator

- From: Winnipeg, Canada

- Registered: 2002-08-20

- Posts: 8,200

- Website

Passenger module for Shuttle

People are talking more today about commercial space. This reminded me of an idea I had in the 1980s, before the Challenger accident. People thought space was becoming commercialized. That Shuttle was the way to make access to space easy, affordable, and common. The airline pilot's union thought they had to learn how to fly Shuttle, because Shuttle would replace commercial airline aircraft. So the pilot's union started organizing a training class for their pilots to learn to fly Shuttle.

While all this was happening, people compared space to the aircraft industry. How aircraft were expensive, only really becoming available to the public when large aircraft could transport a large number of passengers on a single flight. Roughly 100 passengers in a single aircraft. The DC-3 had revolutionized the airline industry. So how could we do that for space?

I had conceived of a passenger module for Shuttle. This module would fill the cargo hold. That cargo hold was able to hold a cylinder 15 feet diameter, and 60 feet long. The hold had ribs for structural strength. The top half of that cylinder was covered by cargo bay doors, fitting around the top half of the cylinder snugly. The bottom half had a flat floor, with flat vertical sides. The ribs held the bottom of a cylinder, but there was space between ribs.

My idea was a passenger module that would look similar to commercial jet airliner. It would have one central isle with two seats on either side of the isle. Each seat the size of an economy class airline seat. This module would have overhead storage bin, and under-seat storage just like an airliner. However, while commercial airliners are configured for you to store luggage under the seat ahead of you, this would provide space under your own seat. The reason is during launch, the shuttle is pointed nose up. You passengers lie on their back. Luggage would slide out. So luggage needs a wall behind the luggage to prevent slide out during launch, and before launch. So place your own luggage under your own seat, between your legs. The back of that space would have not just a bar as a stop, but a compartment with a back wall to ensure small, loose items to slide out.

This module would have 13 rows of seats. The front would have an airlock with docking hatch on top of the air lock. Shuttle had an airlock that fits inside the mid-deck, or outside in the cargo bay. But when preparations for ISS began, they designed a new airlock with a docking hatch for ISS. This passenger module would completely fill the cargo bay, from back to front, and connected to the hatch to the mid-deck. So the passenger module would have to include its own airlock and docking hatch. One reason for integrating is so the entire width of the cargo bay can be utilized. Beside the airlock would be an airline bathroom. And a ladder to the lower deck of the passenger module. The lower deck would have another 13 rows of seats.

The upper deck would have full head room for the isle. Like an airliner, above seats would be a panel with reading light, air vent, emergency oxygen mask, and above that the overhead storage compartment. The storage compartment is integrated with curvature of the cylinder of the airline fuselage. For this module, it would be integrated with curvature of the pressure module. This cylinder would be the same diameter as the Multipurpose Logistics Module. That means the lower deck has a flat ceiling, and the floor is curved. So the isle would have a the same head room as the upper deck, but seats would be on a raised platform. The reading light, air vent, and oxygen mask would be right on the ceiling of the lower deck. The raised platform would have a door on the side, accessible from the isle. This would open to an under-floor storage compartment the same size as the overhead storage compartment of the upper deck. Under-seat storage would be the same. So the lower deck would have the same storage per person as the upper deck.

The Shuttle mid-deck has the galley, bathroom, and 3 seats. The flight deck has seats for the pilot, co-pilot, and two back seats for additional astronauts. The passenger module would have one airline bathroom, so together with the mid-deck bathroom, that's a total of two. The 3 seats in the mid-deck would be used for stewardesses (flight attendants). The two flight deck back seats could be used for two more flight attendants, or mission specialists, or just left as "jump seats" like an airliner.

Shuttle life support is sized for 7 astronauts, so crew in the flight deck and mid-deck. This passenger module would have to provide its own life support. That's why I mention space between Shuttle cargo bay ribs. I thought to put additional oxygen bottles and even lithium hydroxide canisters there. Part of the passenger module, but lumps dangling below the cylinder to fit between Shuttle ribs. Well, looking at Shuttle plans in more detail, the majority of those spaces were already used. They were used for oxygen bottles for Shuttle, and similar equipment. Oops.

Calculating size: 13 rows, 2 seats either side of the isle, that's 4 seats per row, so 13*4 = 52 seats per deck. With 2 decks, that 104 passengers. Now that is on par with a commercial airliner. However, I tried yesterday and today I tried to google images of airline seating plans, showing cross section of the fuselage. This would show seats, isle, and overhead storage bins. The multipurpose logistics module neatly fit in Shuttle's cargo hold, it was 15 feet diameter. I didn't find any airline aircraft that exactly matches that. Narrow body aircraft are narrower, and wide body aircraft are wider. This is an awkward in-between size. But it's wider than a Boeing 737. The outside fuselage width of a 737 is 12 feet 4 inches. And that has 3 economy class seats on each side of the isle. Oh! So this module is larger than I thought. In fact, with 15 feet width, it could accommodate 3 business class seats on each side of the isle. That's important because life support would have to be within the cylinder. So shorten to 11 rows for each deck, with life support in the back. You make it 10 rows, with business class leg room. However, I still mean seats like a 737, not "pods" like a 777. So 3 seats on each side of the isle means 6 seats per isle, 10 rows, 2 decks: 6*10*2=120 seats. That still means more total seats.

Obviously this passenger pod would not have any windows. It would be inside the cargo hold, so any windows would only see cargo hold walls. Each seat back would have a flat screen display, you could use it to display video of your own launch. The Shuttle would include a high resolution "smart phone" camera mounted on the dashboard of the flight deck, lookout out through the windshield. So you could watch the same view the pilot sees. Or other small cameras mounted strategically around the Shuttle.

It used to be common that airlines had a flat screen display built into the seat in front of you. I read that has been discarded because so many people fly with a laptop or smart phone. However, with no window, you would still want something to view. And during launch passengers will want to see something, but you don't want loose laptops during Shuttle launch. So this passenger module would need displays.

The launch pad was designed to allow cargo to be inserted into the Shuttle cargo hold on the launch pad. So passengers could get into their seats, and strap on their seat belts while on the ground and horizontal. The module would be lifted by crane to the shuttle, and inserted into the cargo bay. Yea, that means lifting the module with passengers inside. The alternative is building a ladder into the floor of the isle, and asking passengers to climb down that ladder the full length of the module. That's almost the full length of the cargo bay. Shuttle astronauts did get in while the Shuttle was on the pad. But they climbed within the mid-deck, and flight deck, not the cargo bay. If you put a bulkhead in front of the front row, and back wall separating the passenger compartment from life support, that means 10 rows. JAL airlines has 97cm (38 inch) seat pitch for domestic flights. "Seat pitch" means length from the back of your seat to the back of the next seat in front of you. Economy class seat pitch could be 28 to 31 inches depending on airline. With 10 rows at 97cm that's 9.7 metres (31 feet 10 inches) from front bulkhead to back wall. Quite a fall. Do you want passengers climbing down a vertical ladder that high?

Next thing is an orbital hotel as destination. With 120 passengers, each with no checked luggage but 2 pieces of carry-on luggage. One in the overhead bin, one beneath the seat.

Last edited by RobertDyck (2016-03-10 12:24:00)

Offline

Like button can go here

#2 2016-03-07 13:47:48

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 8,199

Re: Passenger module for Shuttle

You need a lift vehicle that takes off horizontally. A number of studies were done to determine the feasibility of HTHL. The most realistic design was Star Raker. That vehicle could hold as many people as a jumbo jet.

Offline

Like button can go here

#3 2016-03-07 14:25:19

- RobertDyck

- Moderator

- From: Winnipeg, Canada

- Registered: 2002-08-20

- Posts: 8,200

- Website

Re: Passenger module for Shuttle

Could have been done with Shuttle. But we don't have it anymore. ![]()

Offline

Like button can go here

#4 2016-03-07 18:25:57

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 29,476

Re: Passenger module for Shuttle

Much like the ISS topic on what can we do with it once partners and Nasa say we are done with it but not throwing into the ocean we as a group that that for the money that we should repurpose it.

There was a shuttle topic to the same end and I am not sure if it survived...

Using it as a commercial carrier was one of those on the back of the napkin discusion.....

Edit: found it.....

Offline

Like button can go here

#5 2016-03-08 20:02:17

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 8,199

Re: Passenger module for Shuttle

We're going to wait an entire decade before a flight certified spacecraft or launch vehicle is available and there's no guarantee that our next President or Congress won't kill Orion and SLS. Put the orbiters back together and use them for what they were designed to do or store them at KSC for future use. In the end, Lockheed-Martin and Boeing will ensure that Orion and SLS cost just as much as the Space Shuttle, if not more. So much for all the malarkey about how the STS program prevented us from going anywhere beyond LEO.

Offline

Like button can go here

#6 2016-03-09 00:21:57

- RobertDyck

- Moderator

- From: Winnipeg, Canada

- Registered: 2002-08-20

- Posts: 8,200

- Website

Re: Passenger module for Shuttle

I'm not sure what to say. I definitely wanted to see the Shuttles continue to fly. They weren't what NASA wanted in 1968, but were good ships. Contractors went out of their way to ensure constantly increasing cost. NASA and the Air Force noticed this, and identified this as a problem, but were unable to stop it. After the Columbia accident, there was a 50% per-launch cost increase. This should have been a one-time cost to address issues, but contractors ensured this was on-going. These costs meant Shuttle was no longer viable.

The Flight Service Structure has been dismantled, chopped into pieces. It's scrap. Pad A has been converted to use by Falcon Heavy. Pad B has been converted for SLS.

Remaining orbiters have been stripped of all engines: main engines, OMS, and RCS. Main engines will be used for SLS. Stripped orbiters have been sent to museums. Could orbiters be rescued and reassembled? Yes. Launch pad B is now a "clean pad". Saturn V used a service structure mounted on the mobile launcher. That was removed when it was converted for Shuttle use, it was renamed "Mobile Launch Plantform" because it was just a plantform, no tower. Pad B is now intended to service multiple launch vehicles, so could still launch Shuttle. However, without a Flight Service Structure (static and rotating), it would require some sort of mobile service structure. At least something to carry propellant fill hoses, and elevator for astronauts. I believe the Saturn V service structure removed from 2 of the 3 mobile launchers were converted to the Static Service Structures on the pads. The tower used to launch Apollo 11 was chopped into pieces and left to rust in the grass. Museum people wanted to restore it as a museum display. Could one of these 3 be restored as a tower on a mobile launcher? Configured for Shuttle? Possibly. But it would be a lot of work. Expect Old Space contractors to demand brand new everything, and to charge even more than per-launch cost of the last year Shuttle flew.

Boosters for SLS Block 2B haven't been selected yet. Multiple news announcements said the Advanced Booster Competition would be held in 2015. That year has come and gone, and no decision announced. If they go with liquid booster, Shuttle could use it. NASA wanted liquid boosters for Shuttle for as long as there was a Shuttle. And these boosters will be more powerful than 4-segment boosters. That should be enough increased thrust to envelop external tank insulation in plastic film. I suggested that on this forum after Columbia. NASA responded by saying it would add too much launch mass. But could advanced liquid boosters compensate for that? With no O-rings, a Challenger accident would be impossible. With foam enveloped in plastic film, a Columbia accident would be impossible too. Safe enough for passengers?

Offline

Like button can go here

#7 2016-03-09 02:20:48

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 8,199

Re: Passenger module for Shuttle

I'm not sure what to say. I definitely wanted to see the Shuttles continue to fly. They weren't what NASA wanted in 1968, but were good ships. Contractors went out of their way to ensure constantly increasing cost. NASA and the Air Force noticed this, and identified this as a problem, but were unable to stop it. After the Columbia accident, there was a 50% per-launch cost increase. This should have been a one-time cost to address issues, but contractors ensured this was on-going. These costs meant Shuttle was no longer viable.

Just dreaming here:

Re-write the flight software in C

Refit modern avionics and cockpit instrumentation using technology development from the Orion program

Install the improved fuel cells

Develop robots for orbiter parts inventory handling the same way the Anniston Depot uses robots for M1 tank parts inventory handling

Develop a robot for TPS inspection and repair

Develop a mobile crane for orbiter mating

Upgrade the orbiter landing gear to enable return of heavier payloads

Pay Scaled Composites to develop a variant of StratoLaunch that can return the orbiters to KSC in a single flight

Pay ATK to develop expendable SRB's with composite casings with a single O-ring design

Pay Boeing to develop composite tanks for the ET

Use polymer aerogel SOFI on the ET

If we do all that, I think we can get the marginal flight costs in the $200M range. It's clearly not competitive with a Falcon Heavy or Vulcan, but it can recover 4 RS-25's from a SLS flight if the core stage makes it to orbit. RS-25's cost $72M per copy, but more importantly each engines is constructed over the course of 2 years.

STS could also take prospective Martians to ISS for transfer to a Mars colony.

With 100 pax, that's only $2M a head. Not bad for a ride to orbit. I still haven't figured out the economics for delivery to Mars yet, but you have to get to orbit first.

The Flight Service Structure has been dismantled, chopped into pieces. It's scrap. Pad A has been converted to use by Falcon Heavy. Pad B has been converted for SLS.

A mobile and adaptable flight service structure that can service a variety of launch vehicles and payloads is required.

Remaining orbiters have been stripped of all engines: main engines, OMS, and RCS. Main engines will be used for SLS. Stripped orbiters have been sent to museums. Could orbiters be rescued and reassembled? Yes. Launch pad B is now a "clean pad". Saturn V used a service structure mounted on the mobile launcher. That was removed when it was converted for Shuttle use, it was renamed "Mobile Launch Plantform" because it was just a plantform, no tower. Pad B is now intended to service multiple launch vehicles, so could still launch Shuttle. However, without a Flight Service Structure (static and rotating), it would require some sort of mobile service structure. At least something to carry propellant fill hoses, and elevator for astronauts. I believe the Saturn V service structure removed from 2 of the 3 mobile launchers were converted to the Static Service Structures on the pads. The tower used to launch Apollo 11 was chopped into pieces and left to rust in the grass. Museum people wanted to restore it as a museum display. Could one of these 3 be restored as a tower on a mobile launcher? Configured for Shuttle? Possibly. But it would be a lot of work. Expect Old Space contractors to demand brand new everything, and to charge even more than per-launch cost of the last year Shuttle flew.

See above.

Boosters for SLS Block 2B haven't been selected yet. Multiple news announcements said the Advanced Booster Competition would be held in 2015. That year has come and gone, and no decision announced. If they go with liquid booster, Shuttle could use it. NASA wanted liquid boosters for Shuttle for as long as there was a Shuttle. And these boosters will be more powerful than 4-segment boosters. That should be enough increased thrust to envelop external tank insulation in plastic film. I suggested that on this forum after Columbia. NASA responded by saying it would add too much launch mass. But could advanced liquid boosters compensate for that? With no O-rings, a Challenger accident would be impossible. With foam enveloped in plastic film, a Columbia accident would be impossible too. Safe enough for passengers?

There probably won't be any liquid boosters. There's no room for the TSM's on the pad. Advanced solids are good enough, though. Who wants a smooth ride, anyway? That's the most fun you're going to have for six months if you're going to Mars.

Offline

Like button can go here

#8 2016-03-09 10:11:34

- GW Johnson

- Member

- From: McGregor, Texas USA

- Registered: 2011-12-04

- Posts: 5,968

- Website

Re: Passenger module for Shuttle

There's no reason a solid cannot be reliable and safe, as long as you stay away from overly-complex O-ring joints, and you stay away from putting pooky in the insulation joints. We've discussed this elsewhere and before, many times, on these forums.

The only knowingly-incurred problem is that once lit, you simply cannot turn them off. They will burn to completion, just like a stick of dynamite, albeit much slower. You knowingly accept that to get the "wooden round" simplicity and extreme frontal thrust density of the solid. It puts the onus on you to design for crew escape from a heavily-thrusted, accelerating vehicle.

GW

GW Johnson

McGregor, Texas

"There is nothing as expensive as a dead crew, especially one dead from a bad management decision"

Offline

Like button can go here

#9 2016-03-09 11:45:57

- RobertDyck

- Moderator

- From: Winnipeg, Canada

- Registered: 2002-08-20

- Posts: 8,200

- Website

Re: Passenger module for Shuttle

There's no reason a solid cannot be reliable and safe, as long as you stay away from overly-complex O-ring joints, and you stay away from putting pooky in the insulation joints. We've discussed this elsewhere and before, many times, on these forums.

Yes, you said that. And the solids were safe enough to return Shuttle to flight. But this discussion is about a passenger module. Would solids with a joint of any sort right beside a liquid hydrogen tank be safe enough for over 100 commercial passengers?

Offline

Like button can go here

#10 2016-03-09 14:25:01

- GW Johnson

- Member

- From: McGregor, Texas USA

- Registered: 2011-12-04

- Posts: 5,968

- Website

Re: Passenger module for Shuttle

If it was "safe enough" for a 7-crew shuttle, why not for more on board? I guess it really boils down to how much risk one wants to take to achieve some end result. There's still nothing about rocket flight that is really "safe" in the sense most civilians use that word.

I would think that there is at least as much reason for concern about the turbopump assemblies on the liquid rocket engines of almost any configuration we care to think about. Those are inherently short-life items. And if vigilance relaxes (or even if luck just goes bad), it can fail on the one flight. The refurbished Russian engines did exactly that to Orbital Science's booster rocket a few months ago. Fortunately, no one was aboard.

As for recovering and refurbishing shuttle airframes, it might be possible, but you have to understand, those airframes were extensively used, and are at least a little "tired" (metal fatigue). Both propulsion and working TPS were removed. Most of the instrumentation is either horribly obsolete, or has been removed, or both. My guess is that all the thrusters and orbital maneuvering engines were removed, as well.

My other guess is that a new design from scratch would be crudely the same expense as returning these tired old relics to flight status. Neither seems very likely to me. I know of no aircraft put on display that were ever returnable to flight status (there was one partial exception). Only a few of those in the Arizona boneyard were ever recovered and flown. A small subset of that subset-not-stripped-for-parts proved re-flyable.

The lone exception was the B-36D that had been on public display in Fort Worth, Texas. The public did not do fatal damage to its airframe. Enough instruments survived to run one engine at a time, and they ran all 6 R-4360's that way. But not all 6 at once. Without enough parts, the bird was doomed not to ever fly again, although the potential to fly is still there.

The only other B-36 still in existence at all, is the one at the USAF museum, WPAFB, Dayton, Ohio. That one cannot ever be refurbished. Its wing spars were cut to move it to its display site. If things like that were done to the shuttle airframes now on display, then they will never fly again, either.

GW

GW Johnson

McGregor, Texas

"There is nothing as expensive as a dead crew, especially one dead from a bad management decision"

Offline

Like button can go here

#11 2016-03-09 19:19:19

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 29,476

Re: Passenger module for Shuttle

The first orbiter, Enterprise, was built for Approach and Landing Tests and had no orbital capability. Four fully operational orbiters were initially built: Columbia, Challenger, Discovery, and Atlantis. Of these, two were lost in mission accidents: Challenger in 1986 and Columbia in 2003, with a total of fourteen astronauts killed. A fifth operational orbiter, Endeavour, was built in 1991 to replace Challenger.

The Space Shuttle Endeavour, the orbiter built to replace the Space Shuttle Challenger, cost approximately $1.7 billion.

Two of the program's 134 flights have ended in tragedy, killing 14 astronauts in all. Recent NASA estimates peg the shuttle program's cost through the end of last year at $209 billion (in 2010 dollars), yielding a per-flight cost of nearly $1.6 billion. And the orbiter fleet never flew more than nine missions in a single year. The average cost to launch a Space Shuttle is about $450 million per mission. With the total used years of NASA's Shuttle Program Cost $209 Billion — Was it Worth It, is a commonly asked question.

That said the current proposed launch system could not ferry this sort of quantity of people (100) to orbit let along back to earth. So recreating a newer improved shuttle is far off the list of to do for Nasa.....

Offline

Like button can go here

#12 2016-03-09 20:30:12

- RobertDyck

- Moderator

- From: Winnipeg, Canada

- Registered: 2002-08-20

- Posts: 8,200

- Website

Re: Passenger module for Shuttle

Announcements at the time claimed that Enterprise was built to be flight hardware. When they completed it, orbiter mass was greater than they expected. It was too heavy to fly. Fixing that required completely redesigning structural members inside the wings. That couldn't be fixed, it required tearing it apart and rebuilding. Rather than trying to fix it, they used it for approach and landing tests. They didn't even bother applying heat shield tiles, just applied paint in the same pattern. So of the original 5 flight orbiters ordered, only 4 were space worthy.

Last edited by RobertDyck (2016-03-09 20:45:18)

Offline

Like button can go here

#13 2016-03-10 16:14:55

- RobertDyck

- Moderator

- From: Winnipeg, Canada

- Registered: 2002-08-20

- Posts: 8,200

- Website

Re: Passenger module for Shuttle

Wikipedia article: Shuttle Carrier Aircraft

In 1988, in the wake of the Challenger accident, NASA procured a surplus 747-100SR from Japan Airlines. Registered N911NA it entered service with NASA in 1990 after undergoing modifications similar to N905NA. It was first used in 1991 to ferry the new shuttle Endeavour from the manufacturers in Palmdale, California to Kennedy Space Center.

Based at the Dryden Flight Research Center within Edwards Air Force Base in California the two aircraft were functionally identical, although N911NA has five upper-deck windows on each side, while N905NA has only two.

Shuttle Carrier N911NA retired on February 8, 2012 after its final mission to the Dryden Aircraft Operations Facility in Palmdale, California, and will be used as a source of parts for NASA's Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA). Meanwhile N911NA is being loaned out for display to the Joe Davies Heritage Airpark in Palmdale, California, beginning in September 2014.

Shuttle Carrier N905NA was used to ferry the retired Shuttles to their respective museums. It returned to the Dryden Flight Research Facility at Edwards Air Force Base in California after a short flight from Los Angeles International Airport on September 24, 2012. It was intended to join N911NA as a source of spare parts for NASA's SOFIA aircraft. NASA engineers surveyed N905NA and determined that it had few parts usable for SOFIA, and 905 is now intended to be preserved and displayed in Houston. Three former NASA aircraft are on static display in the Houston area - two T-38s at the front entrance of Space Center Houston, and the former NASA KC-135 930 Vomit Comet. In 2013, the Space Center announced plans to display SCA 905 with the mockup shuttle Independence mounted on its back. NASA 905 was erected on site at the space center, having been dismantled and ferried in seven major pieces, (called The Big Move) from Ellington Field, and the replica shuttle was mounted in August 2014.

Sounds like N911NA is still intact.

Offline

Like button can go here

#14 2016-03-11 21:48:42

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 29,476

Re: Passenger module for Shuttle

Well we might not have a shuttle or the Burran to make this happen with but maybe the ISRO to test plane-shaped reusable rocket Currently, the cost of placing 1kg of object in space is about Rs.3 lakh ($5,000) which scientists are hoping can be brought down to about Rs.30,000 ($500).

India will test a small aeroplane-shaped vehicle this year as part of its programme to develop a reusable space launch vehicle to travel up to 70 km and will return. Ya its just a technology demonstrator -- weighing around 1.7 tonnes.....

Offline

Like button can go here

#15 2016-03-16 16:55:37

- Quaoar

- Member

- Registered: 2013-12-13

- Posts: 665

Re: Passenger module for Shuttle

If it was "safe enough" for a 7-crew shuttle, why not for more on board? I guess it really boils down to how much risk one wants to take to achieve some end result. There's still nothing about rocket flight that is really "safe" in the sense most civilians use that word.

I would think that there is at least as much reason for concern about the turbopump assemblies on the liquid rocket engines of almost any configuration we care to think about. Those are inherently short-life items. And if vigilance relaxes (or even if luck just goes bad), it can fail on the one flight. The refurbished Russian engines did exactly that to Orbital Science's booster rocket a few months ago. Fortunately, no one was aboard.

GW

Even in expander cycle?

Offline

Like button can go here

#16 2016-03-17 11:40:48

- GW Johnson

- Member

- From: McGregor, Texas USA

- Registered: 2011-12-04

- Posts: 5,968

- Website

Re: Passenger module for Shuttle

Hi Quaoar:

Yeah, I'm afraid so.

All rocket engine turbo-pump assemblies are inherently one-shot or limited-life items, because the conditions are just so harsh. A refurbishable/reusable rocket engine will have its turbopump assembly replaced every , or every few, flights. There's just no way around that....

.... except direct pressure-feed (very heavy tanks), solids, or the kind of piston-pump assembly that XCOR has been developing, which seems to be very effective, but only pays off in smaller sizes.

GW

GW Johnson

McGregor, Texas

"There is nothing as expensive as a dead crew, especially one dead from a bad management decision"

Offline

Like button can go here

#17 2023-01-19 12:15:40

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 21,543

Re: Passenger module for Shuttle

This topic by RobertDyck seems (to me at least) like a good place to drop off a bit of Google search about the Space Shuttle.

how long was the space shuttle in meters

Camera searchAll

ImagesVideosNewsBooksMore

Tools

About 32,200,000 results (0.51 seconds)

about 37.1 m

The Orbiter was the primary component of the shuttle; it carried the crew members and mission cargo/payload hardware to orbit. The Orbiter was about 37.1 m (122 ft) long with a wingspan of about 23.8 m (78 ft).The Space Shuttle and Its Operations - NASAhttps://www.nasa.gov › centers › johnson › pdf

I decided to ask Google to refresh memory of the length of Shuttle, since the vehicle in early development by Space-Plane.org would be 60 meters long.

The Shuttle was designed for dead-stick landings. I'm not sure what the folks at Space-Plane.org have in mind, but some sort of air-breathing engine for landing would be handy, if the mass required for that component is affordable.

Planned landings in the ocean (off Florida or California or Texas) would be an alternative to having to install wheels for landings.

If the heat shield/outer skin is planned for one flight use (ie, expendable) then landing on the belly shield in water would not be a problem.

Plus, the emergency landing "field" would be practically the entire Earth, if that design choice were made early on.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#18 2023-01-19 14:23:18

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 8,199

Re: Passenger module for Shuttle

tahanson43206,

Even keeping the wings level while powering something with the size and weight of a Space Shuttle requires jet airliner thrust levels. The empty weight of the Space Shuttle was just below that of the original / "short" model Boeing 767, and it would certainly weigh the same with consumables and passengers aboard. A 767 is also a lot more aerodynamic than a Space Shuttle, too. You'd need at least 65,000lbf for a minimal rate ascent. Pratt's 4060 model, which powers the 767, is a bit over 8 feet in diameter and about 13 feet long. However, those things also weigh almost 16,000lbs. If you had to carry that engine, plus a supply of Jet-A for 15 minutes, plus passengers, my guess is that you'd have to cut into payload by quite a bit. This is something that has to be designed into the vehicle, from the start of the program.

Pratt & Whitney's 4060 is clearly way too big, but 6 of the J52-P-409 (PW1212) could work. No idea what that specific engine model weighed, but 14,220lbs for 15 minutes of fuel at full thrust with the same TSFC as ye olde J52s used in my former squadron's Prowlers, plus at least 13,908lbs for all 6 engines. Those engines are about 10 feet long and have a diameter of 38 inches. I figure around 31,000lbs for the entire setup. 100 passengers per flight is about right. That's all you could take. STS would have no more payload performance left. 100 passengers in suits with minimal consumables and personal belongings, and that's it.

20 of the Williams FJ-44-4s could also work, and 20 engines would weigh 13,160lbs. Those turbofans are about 25 inches in diameter and only 53 inches long. Physically speaking, there's enough thickness / chord / span, found within each of the orbiter's wings, to mount 10 engines per wing, plus fuel. That would provide 72,000lbf in total, which is enough fuel for maybe two go-arounds if the first landing attempt fails. You're cutting deep into the orbiter's payload performance, though. I'm guessing the advanced boosters could restore some of that, but not all of it.

A better option is to not screw up the landing. No landings were seriously fouled up during the STS program. I have to believe that wasn't just luck. I'm pretty sure the pilots knew what they were doing.

Offline

Like button can go here

#19 2023-01-19 15:46:57

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 21,543

Re: Passenger module for Shuttle

For kbd512 re #18

I have wished for a Like button for posts in NewMars (I seem to recall OldFart1939 making a similar observation).

Thank you for a thoughtful and informative post about the Space Shuttle and the question of powered flight to a landing.

Since this ** is ** RobertDyck's topic about a passenger module for Shuttle, your reply seems to me to be perfect match.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#20 2023-01-20 20:05:03

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 8,199

Re: Passenger module for Shuttle

tahanson43206,

The biggest problem I see with achieving powered flight with the orbiters is that they were purposefully designed to function like giant air brakes during reentry, so you need a lot of thrust just to stay airborne- much more than a 767 would need to climb using a single engine. There's not a practical way to overcome that. It requires a lot of added weight, for little real benefit. You also need much more powerful SRBs, up-rated RS-25s, and a bigger external tank to restore some of your lost payload performance to orbit. Basically, you need SLS-like performance from this proposed STS program variant vehicle.

The passenger module would need to be integrated into the orbiter's cargo bay, in order to save weight, and it would need to be very "spartan" inside. The orbiter would also require much more efficient radiators to dump the excess thermal load generated by 100+ warm bodies in a very confined space, along with much more powerful fuel cells to keep them alive. More and more added weight is what this boils down to. It would be a tall order using today's technology, but virtually impossible using 1970s or 1980s technology. That's probably why it was never done. We simply lacked the requisite tech to create a passenger variant of the Space Shuttle. We also lacked a place to house them in orbit (a giant space station with artificial gravity), as well as a mission profile mandating the presence of 100+ workers.

The real question is how we're going to reliably do this today for the upcoming Mars colonization effort. I think a HTHL SSTO with full reusability is the correct solution, something akin to the British Skylon, with takeoff assistance provided by EMALS to accelerate the vehicle up near the speed of sound before it ever leaves the ground. We need to almost guarantee a go-around landing attempt in the event that the engines fail or the vehicle is unable to attain orbit. A rocket cannot do that. I think putting them in the upper stage of a highly complex super heavy lift rocket, best used to deliver real tonnage to orbit (but for cargo), is a mistake.

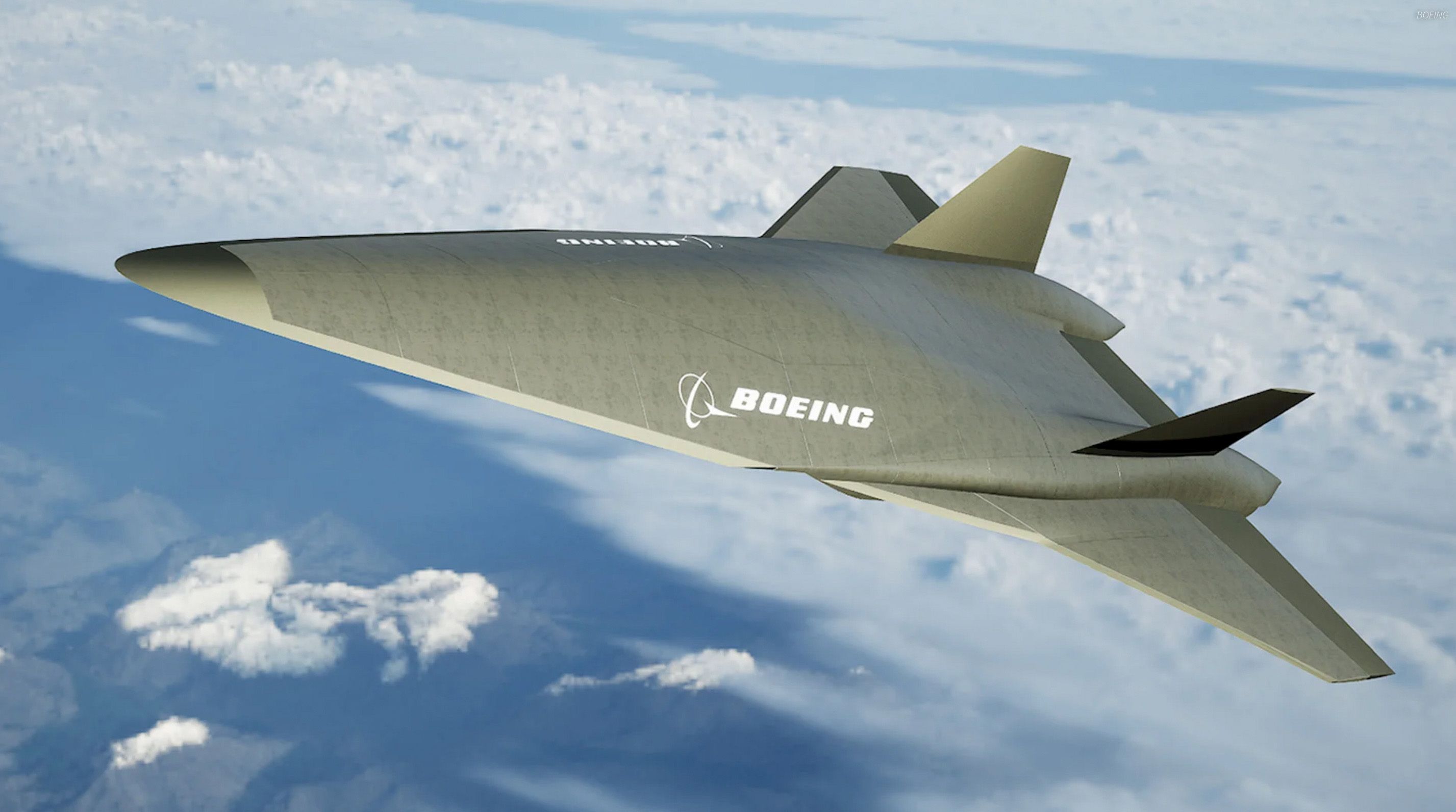

I don't know if the ultimate solution likes like a bullet with wings or a cheese wedge with wings, but it has to be something along the lines of these:

Aircraft that takeoff and land like normal aircraft are the only kinds of aircraft that routinely operate day-in and day-out from facilities that resemble normal airports, carrying millions of paying passengers to various destinations. As such, any interplanetary personnel transport service will have to operate this way. There aren't any vertical takeoff and landing aircraft that carry millions of passengers anywhere, because vertical takeoff and landing require extreme propulsion efficiency and reliability in order to function acceptably well. I've seen nothing to change my mind on any of this, including Falcon boosters or the eventual launch of Starship.

Look at the vertical takeoff battery powered taxi experimental aircraft. How many are routinely carrying passengers anywhere?

The answer, of course, is none. They lack the range and reliability to be useful transports for ordinary / everyday people to use. If you're creating a second branch of human civilization, then you're necessarily talking about ordinary people at a point very near to the beginning of that endeavor. So, for interplanetary flight to become routine and reliable enough for the general public to use, something akin to a "normal" jet airliner (but also capable of attaining orbit), is mandated.

The flying public didn't start off using helicopters. The helicopters came much later, and to this day they remain the exclusive domain of exceptionally wealthy individuals who don't have to ask what the ticket costs. If a Robinson R-22 (a 2-seat helicopter with a 125hp 4-cylinder air-cooled piston engine- early 20th century motorcycle engine technology) is still not a practical / attainable means of personal transport for someone who wants a taxi service to fly across a city to save time on their daily commute, then what makes anyone think an aircraft that costs vastly more to operate, per seat-mile.

The new Curti Zefhir helicopter weighs 699kg at maximum load, but just 300kg empty and 40 gallons of Jet-A (123kg). The entire carbon fiber composite airframe weighs in at a svelte 72kg (lighter than I am by about 35lbs, for a two-seat airframe that's longer than my Cadillac Escalade). It's powered by a PBS TS100 141shp gas turbine engine. It costs $500,000 USD. The Zefhir is a physically beautiful and highly capable machine for its size, but at a half million dollars per copy, the total number of people who can afford to buy or use one, and therefore benefit from its use, approaches statistical zero, with respect to the total human population. This is a "base model professional vertical transport machine". The Robinson R22 costs $318,000 USD, so the difference between piston and gas turbine power is not "night-and-day different" in this class of vertical transport vehicle.

The Lithium-ion battery powered Joby Aviation "tilt-rotor" (think battery-powered V-22 Osprey, but with almost none of the range or payload carrying capacity of the Osprey) costs upwards of $4,000,000 USD, with competitor Archer Aviation producing a similarly costly machine. Anyone who thinks a vertical takeoff and landing machine that can go from zero to Mach 25 and then back to zero again, for any remotely comparable total cost, is living in dreamland. Zefhir burns about 12.5 gallons per hour in cruise, so at $3 per gallon (local Jet-A prices here in Houston), that's $9,375 per year. If you operate the vehicle 250 hours per year, then you pay $93,750 over 10 years of operations. That's a tiny fraction of the cost of the battery powered nonsense machines pretending to be usable aircraft. So, $600K was too much money for a practical "sky taxi", but a battery powered machine that's 6.7X more expensive, after fuel cost is included for the helicopter, is somehow magically cheaper to own and operate? You could fly that little helicopter for 34 years on $3/gallon Jet-A before reaching purchase price parity with Joby Aviation's S4 battery powered "Osprey-wannabe". It's a toy for rich people. If they ever get the cost even with the Zefhir, something that is almost literally impossible since weight equals cost in commercial aviation, then you might have a case for a crappy helicopter / crappy plane. 300kg empty weight for Curti's Zefhir vs 1,815kg empty weight for Joby Aviation's S4. Oh look, the S4 is about 6X more costly than a Zefhir, plus a little extra for all those extra propellers- 30 propeller blades in total. From personal experience, them thangs ain't cheap. It's almost like cost in aviation is an immutable law, meaning if your shiny new bird weighs 2X more than the one it replaced, then it also costs 2X more. Why? That's how aircraft math works. I can't find any examples where it didn't work that way, except in military procurement where you can wind up with absurd cost overruns because someone else is footing the bill. I'm not hating on Joby, though. Their bird is beautiful, but beauty doesn't pay the bills unless you're a super model.

As such, the notion that ordinary people will be able to go to Mars for $250,000 per person, is wildly delusional thinking. Unless the cost of orbital transport is brought down to levels comparable to commercial airline services, which will most likely occur using machines that greatly resemble prototypical airliners, then no ordinary person will be hopping an interplanetary transport to Mars due to lack of funding.

This is why both endo-atmospheric and exo-atmospheric propulsion methods and total operating cost, matters so greatly. This is why I'm pushing for electric in-space propulsion, primarily using photovoltaics. After you leave the atmosphere, this is the absolute cheapest method for traveling around the inner solar system. If you have solar power satellites to beam power to spacecraft coming and going, then it gets even cheaper. At one time, I supported development of gas core nuclear rockets (for all the benefits GW and RobertDyck and others have pointed out), but we don't even have one of those on the drawing board. A solid core nuclear thermal rocket may be realized in another 10 to 15 years, which would be a boon to Starship by cutting the tonnage of propellant carried in half.

Ideally, we'd have hypersonic surface-to-orbit "spaceliners" (with EMALS launch assist to permit takeoff rejection, fully loaded), followed by nuclear-powered Starships to ferry people to Mars, followed by very efficient and cheap cargo flights using electric propulsion to deliver a steady stream of cargo to support a fledgling Mars colony.

If there was a problem I could personally solve, it's this:

How do we make aviation cheap enough for enough young people to become personally involved in flying?

If we can get enough kids into the cockpit, then one of them will figure out how to solve these problems. I'm quite certain of that.

How can we make an adequate flying machine that allows a new pilot of modest means to learn to fly, for a minor fraction of the purchase and operating cost of a new Cessna 172?

Some of the greatest ace pilots of all time were men and women of very modest means, who nobody thought would make a good fighter pilot, yet proved us all wrong anyway.

I'm talking about a machine that looks / sounds / feels like a real plane, not a flimsy ultralight that can just barely fly. A personal airplane should be an attainable "luxury good" (on the pathway to becoming an aviator, flying airliners or spaceliners or interplanetary transports) for most Westerners, not much more expensive than a new full-sized car or truck. So, how do we get there from here? Personal flying is a "gateway drug" to bigger and better things, like piloting a sleek and sophisticated new spaceliner or Starship to parts unknown. For our children to colonize Mars on our behalf, to ultimately "succeed where we have failed", we need to "get their foot in the door" first.

Offline

Like button can go here

#21 2023-01-20 20:50:20

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 29,476

Re: Passenger module for Shuttle

More powerful SRB and longer burn is why we ended up with a bloated Orion and that is a natural overtone oscillation that re-enforces itself as it burns. The booter ET was also a disposable that as well caused more flaws and inflated costs along with that foam that would degrade after repeated filling and dawn down of cryogenic fuels. The reason for the plane shape was to reduce any chance of saltwater damage to the ship in the design to be more reusable but that only happens if you do not need to do a shield replacement program rather than just an inspection for integrated checks.

The Boeing design is a knock off of the venture star, the second is a stealth version of the hypersonic, while the sled by Darpa is a different animal from the past that was to use the aerospike j2 units. The others are version of scram, ram designs of art.

Offline

Like button can go here

#22 2023-01-20 22:34:44

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 8,199

Re: Passenger module for Shuttle

SpaceNut,

I don't know what the exact "correct solution" happens to be. All I know is that an orbital space transport operable as a normal aircraft must function similarly to a normal aircraft, with a number of design concessions made so that it can achieve orbital velocity and survive the heat of reentry. Any manner of vertical takeoff and landing aircraft tends to be a poor excuse for an aircraft. I don't doubt that they still work, but there are no vertical takeoff airliners in existence because so many design concessions have to be made to achieve vertical takeoff, that the machines become impractical aircraft. Rockets are great at doing what they do, but to my knowledge nobody has ever made a VTOL aircraft with an accident rate anything like that of "normal" fixed-wing aircraft that uses a runway to takeoff and land. Even CATOBAR carrier aircraft are statistically much less likely to crash than VTOL jets.

Whether it is or should be possible to make a reliable VTOL is besides the point. The fact is, pure thrust is not as reliable as wings that generate significant aerodynamic lift, because a very light and powerful engine is required. Most accidents occur during takeoff and landing. There are far fewer in-flight accidents at altitude. If you use an electromagnetic catapult launch to ensure the machine is already flying before it ever leaves the ground, then in all probability it's going to be able to land if there's an in-flight problem. It's less-efficient than using pure thrust for a vertical ascent to orbit, but sometimes efficiency isn't everything. Survivability normally comes first, and then you worry about efficiency. We've had an awful lot of accidents with VTOL machines over the decades. Losing 500 passengers in a single accident, probably at least once per year, is going to be a tough pill for the flying public to swallow.

If SpaceX can make it work, then my hat's off to them. For that to not occur at least once per year if they're flying several times per day, then their rocket needs a level of reliability that no other sophisticated multi-stage rocket has ever demonstrated. Even the Space Shuttle had various RS-25 operational failures during the program, but thankfully none were fatal. If Starship is 99.9% reliable, which would be spectacular for a machine of its complexity and performance characteristics, that's 1 likely catastrophic failure per year, given 1,000 flights per year. Modern airliners are more like 99.999% reliable, which still equates to a crash every other day at their average utilization rates.

Offline

Like button can go here

#23 2023-01-21 09:16:56

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 29,476

Re: Passenger module for Shuttle

As you noted a plane must get a quick acceleration in order to take of horizontal. Even if we had an in-air platform to take off from the plane is still stationary at zero before taking off. The version of the SLI was a bi plane format with the carrier plane being larger than the crewed side of the structure.

This was coming about due to the shuttles being deemed unsafe and to experimental for use.

Sort of like the newer version showing a Dream chaser vehicle

2002 it was hidden under the launch technology development which has the earlier sled design.

https://www.nasa.gov/centers/marshall/p … tfacts.pdf

It was going to use newly development in engines.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Space_Launch_Initiative

It was also part of the Airforces liquid flyback booster desire.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reusable_Booster_System

All of this was to make the launch more reusable.

https://oig.nasa.gov/docs/ig-02-028r.pdf

All of this was canned in favor of rehashing the shuttles systems components not once (constellation) but twice to get to Artemis.

We have all of these incantations of topics here in shuttle derived vehicle SDV plus a few others from that 2004 era.

Offline

Like button can go here

#24 2023-01-21 16:41:07

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 8,199

Re: Passenger module for Shuttle

SpaceNut,

DreamChaser is a miniature version of the Space Shuttle. It's riding atop a multi-stage rocket with solid boosters and a liquid core. So far as I'm aware, it will be launched by Vulcan. The core stage will use BE-4 engines burning LCH-4, with 2 to 4 solid strap-on boosters for extra thrust at liftoff, and be sent to orbit using an RL-10 upper stage burning LH2. Logistically speaking, there's at least as much going on there as the Space Shuttle had going on, but at a smaller scale. Using it will, in actual practice, run afoul the same affordability issues as the much larger and more capable Space Shuttle had. I really like the general concept of a "Mini Shuttle" that separates the cargo from the astronauts, but then they went and included an aft cargo module that's detachable from the vehicle. If I had to guess, SNC and team were meeting a design requirement set forth by NASA for delivering both people and cargo to the ISS or other space stations in LEO. Orbital ATK had the ultimate design for cargo delivery- the "tin can" Cygnus cargo module (which will become part of the Lunar Orbital Gateway). A tin can is useful when it's low-cost and disposable. I'm sure DreamChaser does or can do a lot of things, which is great, but none of them will be done particularly well. It's a government-use-only type vehicle. NASA, using other peoples' money, is the only probable user who is able to afford the ticket prices.

Apart from SpaceX's Starship, there are no other serious efforts to affordably send hundreds to thousands of people into space. I think SpaceX probably has the correct solution for cargo delivery. Whether or not it's reliable enough for routine transport of passengers remains an open question. My "horse sense" is that a HTHL SSTO, with ceramic or tile-based reusable insulation for reentry, and powered by LOX / LCH-4, is the correct way to go.

The Skylon-1000 SSTO concept:

Offline

Like button can go here