New Mars Forums

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

Announcement

#1 Today 14:54:45

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,430

wiki Block 4 starship first mission propellant creation

Not a discussion page

Cargo ship is targeting 200 mT up from the block 3 which is 100 mT

The information on the web indicates that 4 cargo with 2 crewed are thought to be there with fuel to return already waiting but that means those ships needed a dedicated mission to create fuel.

It might look like this with the ships on mars surface.

But what if the mission was a half payload delivery where man setup a system from the cargo and ships that they arrive in.

Ai indicates that

[center][size=150]Starship Block 3 – Fuel Remaining on Mars (50 t Payload)[/size][/center]

Scenario: Block 3 Starship is fully refueled in LEO (≈1200–1250 t propellant) and departs for Mars carrying 50 t of payload.

With a lighter payload than the “maxed out” case, Starship needs slightly less Δv from its tanks, so it arrives with a bit more residual propellant margin—but it still lands effectively “dry” from an operational standpoint.

[hr]

[size=120]Propellant Usage Breakdown (50 t Payload)[/size]

Trans-Mars Injection (TMI): ~850–900 t

Course Corrections: ~10–20 t

Mars EDL + Landing Burn: ~80–120 t

Total Used: ~940–1,040 t

Initial Load: ~1200–1250 t[hr]

[size=120]Estimated Remaining Propellant on Mars[/size]

Remaining = 1200–1250 t - (940–1040 t) Remaining ≈ 160–310 t (in main tanks, gross)However, this “remaining” is not clean, usable ascent propellant:

Main tanks: Largely reserved as performance margin, residuals, and non-usable slosh.

Header tanks: Provide the controlled landing propellant and are nearly empty after touchdown.

Practical, controllable post-landing propellant:

[size=120]Still only a few percent of total capacity, effectively negligible for ascent.[/size]The lighter payload improves margin and robustness, not the fundamental architecture: Starship is still intended to rely on ISRU for any departure from Mars.

[hr]

[size=120]Operational Conclusion (50 t Payload Case)[/size]

Starship lands with more margin than a heavier-payload mission, but still not enough for ascent.

Mission design still assumes full ISRU refueling (~1200 t CH₄/LOX) on Mars for return.

For base planning, you should continue to treat each landed Starship as operationally “empty”.

[center]Even with only 50 t of payload, Starship’s Mars architecture is still: arrive nearly dry, refuel on the surface.[/center]

Seems like something is off as a full payload is expected to be next to nothing but with less payload it should be quite a bit remaining.

Seems that AI gets confused....

Why “Less Payload” Doesn’t Automatically Mean “More Fuel Left on Mars”

1. The landing burn dominates the fuel budget — not the payload mass

On Mars, Starship performs:A long supersonic retro propulsive deceleration

A flip maneuver

A final landing burn

These burns require a minimum fixed amount of delta‑V, regardless of payload.

Even if you remove 50 tons of cargo, the landing sequence still costs almost the same amount of propellant.Payload mass changes the burn slightly, but not enough to leave a meaningful surplus.

Think of it like braking a car from 80 mph to 0 mph — removing passengers doesn’t change the braking distance much.

2. Starship uses header tanks for landing — and they are sized for safety, not efficiency

The landing fuel comes from:CH₄ header tank

LOX header tank

These tanks are:

Small

Fixed‑volume

Filled before EDL

Designed to guarantee a safe landing even in worst‑case conditions

If payload is lighter, the header tanks don’t magically shrink or adjust.

They still contain the same amount of fuel, and Starship still burns most of it to land safely.So the “extra” fuel isn’t in the main tanks — it’s in the header tanks, and it gets used anyway.

3. Mars atmosphere is thin — so payload mass barely affects drag

On Earth, a lighter vehicle slows down more easily.

On Mars, the atmosphere is so thin that drag is weak, so mass doesn’t change the deceleration profile much.Starship still needs nearly the same:

Heat shield performance

Retropropulsive braking

Landing thrust

Thus, fuel savings from reduced payload are tiny.

4. The landing burn must maintain a minimum thrust level

Raptor engines cannot throttle arbitrarily low.

Even if the ship is lighter:The engines must stay above minimum throttle

That means extra thrust

Which means extra fuel burned

This cancels out much of the theoretical savings from reduced mass.

5. Propellant gauging in low gravity is inaccurate

As we discussed earlier:Slosh

Low gravity

Thermal gradients

Pressure transients

All cause fuel readings to fluctuate, making it look like payload changes fuel remaining when it’s really just sensor noise.

The short version

Reducing payload does help a little, but Starship’s Mars landing fuel requirement is dominated by:Fixed landing maneuvers

Header tank sizing

Minimum engine throttle

Weak atmospheric drag

So the leftover fuel doesn’t scale with payload the way intuition suggests.

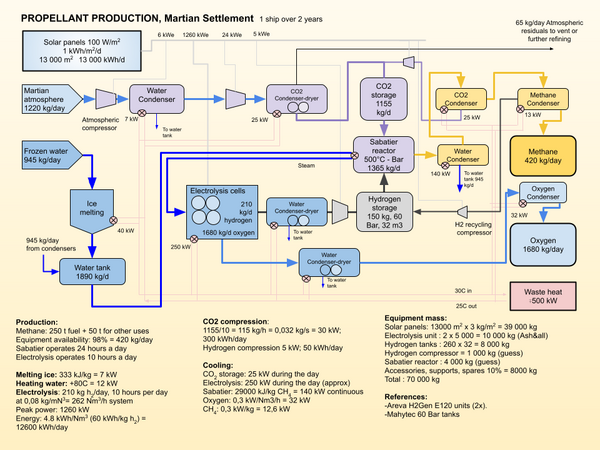

This is what Mars Society has in its planning

what we know for harvesting the atmosphere

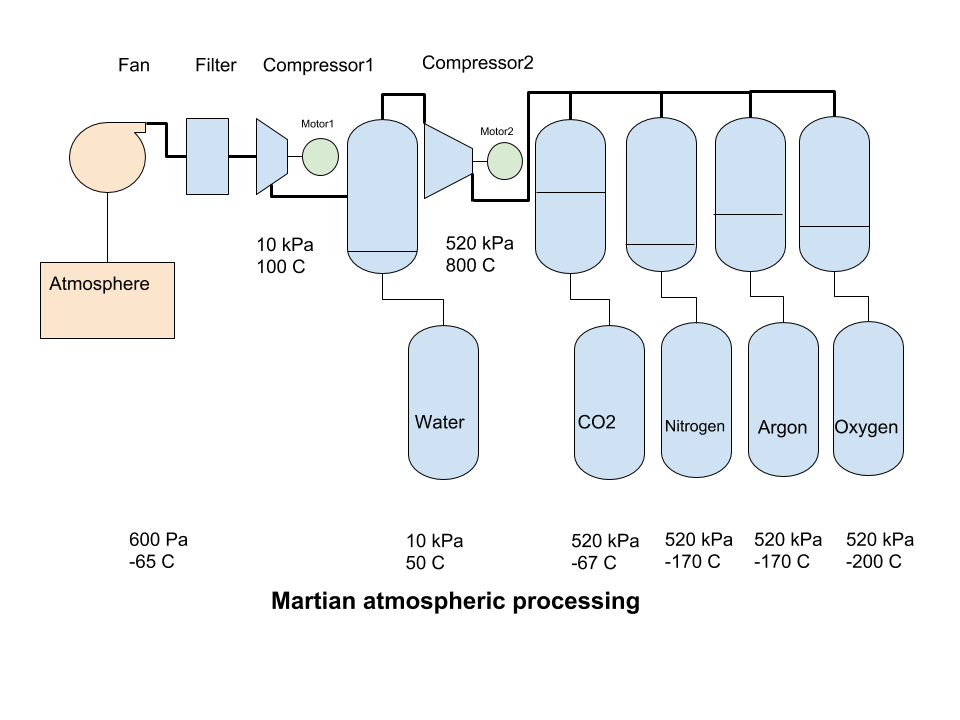

Our engineered atmosphere is 0.5 bar for internal use starting from mars air which is 0.006 bar Composition: 95% CO2, 2.85% Nitrogen, 0.17% Oxygen.

Normal earth air is o2 at 21% for 1.0 bar containing N2 which makes up almost the remaining % of the 14.7 psi.

Of course one of the issues is the quantity of air we need to the volumes that we are living with in and the other is the fuel levels to get back home are huge which makes the power demand high.

Online

Like button can go here

#2 Today 14:55:38

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,430

Re: wiki Block 4 starship first mission propellant creation

Missions that proceed must be able to produce propellant:

Establishing a Mars propellant plant to refuel a Starship for a return trip likely requires several cargo missions, with estimates suggesting 2 to 6+ ships to deliver necessary infrastructure (solar panels, mining equipment) and initial fuel stocks. While some scenarios suggest 3-4 ships can enable a return via in-situ resource utilization (ISRU), initial, safer approaches might use 6+ tankers to establish necessary infrastructure.

Infrastructure Requirements: A fully operational plant capable of producing 1,000+ tons of propellant (methane and oxygen) for a return journey requires substantial power, estimated at 5 GWh, needing ~250 metric tons of equipment, equivalent to 2+ fully loaded cargo Starships.

Fuel Mining & Production: The process involves extracting water ice and capturing \(CO_{2}\) from the atmosphere.

Alternative/Interim Methods: Rather than immediate, full ISRU, early missions might rely on landing 3-4 Starships, where 3 are drained to fuel 1 for the return trip, or using 4-6 ships to establish a rudimentary plant.

Scale: SpaceX aims to send at least 2 uncrewed cargo ships before the first crewed mission to set up power, mining, and life support. Ultimately, the number of ships depends on the efficiency of the ISRU plant, the power capacity installed, and the willingness to risk the first crew's return capability

Water source from Korolev Crater or other location would be of benefit to getting a good start.

Based on current SpaceX Mars mission architecture, establishing a propellant plant on Mars to refuel a Starship for a return journey, utilizing water ice, requires a multi-stage, cargo-heavy operation. Initial Setup Phase: To establish the necessary propellant plant (Sabatier reactors, mining equipment, solar arrays) at a location like Korolev Crater, early, uncrewed missions would need to land several cargo Starships (potentially 2–5) containing roughly 100+ tons of equipment each.Propellant Production Requirement: To refuel a single Starship for a return journey, the plant must produce approximately 1,200 metric tons of propellant (methane and oxygen).Operational

Requirement: While early estimates suggested 1–2 cargo ships worth of equipment could start production, a more robust and faster turnaround (within one synod, or 26 months) likely requires at least 3-4 cargo ships to be active to ensure enough power and water processing capability to produce the ~1,200+ tons of fuel. In summary, to start a plant, 2-5 dedicated cargo Starships are required to land the equipment, with at least 3-4 of them acting as operational plant components/fuel depots to reliably produce enough fuel for one return trip.

Key considerations: Water Source: Korolev Crater is an ideal, high-latitude location (\(73^{\circ }\text{N}\)) with large, accessible, near-surface water ice deposits, reducing the need for deep drilling.

Power: The limiting factor will be the mass of solar panels or nuclear reactors required to power the electrolysis process to turn that water into hydrogen, requiring significant cargo mass for power generation.

Launch Windows: These cargo ships must arrive at least one, if not two, synodic periods (26–52 months) before the crew arrives, to ensure the tanks are full

Of course this brings up mission details and purpose as a stepping stone to get from 1, to 2, to 3 and so on until we have sustainability.

so lets start with the fully refueled starship crewed Block 3 requirements

how much water is required to fill a starship crewed block 3 on mars surface.

To fully fuel a Starship on the Mars surface for a return trip, approximately 600 metric tons of water are required to produce the necessary liquid oxygen and methane propellant via In-Situ Resource Utilization (ISRU). This water is mined from Martian ice and processed using renewable energy. Propellant Production Needs: Generating enough propellant for a return journey requires on the order of 600 metric tons of water.

Alternative Architectures: Some mission plans, such as NASA's DRA6, suggest bringing ~18 metric tons of water from Earth to act as a catalyst with Martian CO\({}_{2}\), while others focus on full ISRU to produce the 600-ton requirement.

Water Volume: 600 tons of water is equivalent to an ice cube approximately 9 meters on each side.

Survival Needs: Beyond propellant, water is necessary for life support (drinking, hygiene), with estimations suggesting 0.6 kg/h/person without full recycling. Mining water locally is considered the most efficient method for long-term Mars missions, rather than transporting it from Earth

how much Co2 is required to fill a starship block 3 on mars surface.

Based on current plans for SpaceX's In-Situ Resource Utilization (ISRU) on Mars, refueling a Starship (Block 2/3) to return to Earth requires approximately 960 to 1,000 metric tons of liquid oxygen (LOX) and 240 to 330 metric tons of liquid methane (LCH4). To produce this propellant, the necessary amount of CO₂ extracted from the

Martian atmosphere is: Total CO₂ Required: Approximately 600 to 700 metric tons to produce the necessary methane via the Sabatier process (\(CO_{2}+4H_{2}\rightarrow CH_{4}+2H_{2}O\)) and for oxygen production, as reported in various propellant plant estimations.

Alternative Calculation: The Sabatier process requires roughly 2.8 tons of CO₂ for every 1 ton of methane produced. Producing ~330 tons of methane (full capacity) requires over 900 tons of CO₂.

Key Considerations for Mars Production: Process: The CO₂ is not just "put into the tank"; it is combined with hydrogen (from split water ice) in a Sabatier reactor to create liquid methane and liquid oxygen.

Surface Operations: 1,500 tonnes of total propellant are needed for a return trip.

Power Requirement: Producing this amount of fuel requires massive energy input, requiring roughly 30,000 \(m^{2}\) of solar panels.

Atmosphere: While the Martian atmosphere is 95% CO₂, it is very thin (0.6% of Earth's pressure), requiring huge amounts of gas to be processed

Now without the block identification:

how much water is required to fill a starship block 3 on mars surface.

To fully refuel a Starship on the surface of Mars for a return trip, approximately 500 to 1,000+ metric tons of water (H₂O) must be mined and processed to produce the required methane (\(CH_{4}\)) and oxygen (\(O_{2}\)) propellants. While specific "Block 3" water requirements are part of evolving architecture, the general consensus for fully fueling a Starship using In-Situ Resource Utilization (ISRU) involves mining roughly 540 to 600 tons of water ice per ship to create the needed fuel. Key Water-to-Propellant Details Production Mechanism: Water is electrolyzed into hydrogen, which is then reacted with Martian carbon dioxide (\(CO_{2}\)) via the Sabatier process to produce methane and oxygen.

Water Requirements: To make 240 tons of methane and 960 tons of oxygen (standard full load), about 540 to 600 metric tons of water must be mined and split.

Alternative Estimates: Some early estimates suggested as much as 1,000+ tons of water, though refined calculations often cite lower amounts, such as 500 tons depending on the efficiency of the mining and conversion process.

Mass vs. Volume: This water quantity is equivalent to a large ice cube roughly 9 meters on a side. Context on Starship "Block 3" and Mars Propellant Load: A full Starship on Mars requires a total propellant load of roughly 1,200 to 1,500 metric tons to return to Earth.

ISRU Feasibility: Mining this amount of water is highly dependent on locating accessible, high-purity water ice on the Martian surface. If the water content in the soil is 50% (underground glacier), 500 tons could be mined in roughly 10 days; at 10% content, it could take two months.

Emergencies: If ISRU is not available, hauling water from Earth is likely prohibited by the immense mass requirements, though a reduced ascent (using only 40 tons of propellant) might only require roughly 18 tons of imported water

how much Co2 is required to fill a starship on mars surface.

Based on current estimates for the SpaceX Starship, roughly 600 to 700 metric tons of CO₂ are required to produce enough methane (CH₄) to refuel a Starship for a return trip to Earth.

This process relies on the Sabatier reaction, which combines carbon dioxide (CO₂) harvested from the Martian atmosphere with hydrogen (H₂) produced from mined water ice (H₂O) to create methane and oxygen (O₂).

Key Data on Mars Refueling

Total Propellant Required: A return trip requires approximately 732 to 1,200 tons of total propellant (liquid oxygen and liquid methane) to lift off from Mars and return to Earth.CO₂ Requirement: Producing the ~240–330 tons of methane needed for this trip requires consuming around 540 to 900+ tons of CO₂.

Source: The CO₂ is directly harvested from the 95% CO₂ Martian atmosphere.Production Time: It is estimated that a fully loaded Starship's worth of oxygen and methane can be produced by an in-situ propellant production (ISPP) plant on the surface in about two years.

ContextByproducts: The reaction also produces roughly 11.8 metric tons of nitrogen and argon as a byproduct, which can be used to pressurize habitats.

Energy Intensity: Creating this fuel requires massive amounts of power, requiring a large-scale solar array or a small nuclear reactor.

Alternative Refueling: If only the oxygen is produced on Mars, and methane is brought from Earth, the CO₂ requirement for manufacturing drops to zero, but the cost of transporting methane increases

So looking at the masses for either the total fuel requirement does bridge a large difference.

Online

Like button can go here

#3 Today 14:57:28

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,430

Re: wiki Block 4 starship first mission propellant creation

[table]

[tr][th]Category[/th][th]Water Required[/th][th]CO2 Required[/th][th]Notes[/th][/tr]

[tr]

[td]Baseline ISRU Requirement[/td]

[td]540–600 metric tons[/td]

[td]600–700 metric tons[/td]

[td]Standard load for producing ~240–330 t CH4 and ~960–1,000 t O2.[/td]

[/tr]

[tr]

[td]Extended Range (Low–High)[/td]

[td]500–1,000+ metric tons[/td]

[td]540–900+ metric tons[/td]

[td]Depends on Sabatier efficiency and methane target mass.[/td]

[/tr]

[tr]

[td]Alternative Architecture (NASA DRA6)[/td]

[td]~18 tons imported from Earth[/td]

[td]0 tons (if methane imported)[/td]

[td>Importing methane eliminates CO2 processing entirely.[/td]

[/tr]

[tr]

[td]Sabatier Stoichiometric Ratio[/td]

[td]Water provides hydrogen for CH4[/td]

[td]2.8 tons CO2 per 1 ton CH4[/td]

[td]Producing 330 t CH4 requires over 900 t CO2.[/td]

[/tr]

[tr]

[td]Propellant Output Supported[/td]

[td]Supports ~1,200–1,500 t propellant[/td]

[td]Same[/td]

[td]Full Mars–Earth return load.[/td]

[/tr]

[tr]

[td]Physical Volume Equivalent[/td]

[td]~600 t = 9×9×9 m ice cube[/td]

[td]N/A[/td]

[td]Useful for visualizing mining scale.[/td]

[/tr]

[tr]

[td]Production Time[/td]

[td]~2 years for full load[/td]

[td]~2 years[/td]

[td]Typical ISPP plant assumptions.[/td]

[/tr]

[tr]

[td]Energy Requirement[/td]

[td]Electrolysis + Sabatier[/td]

[td]CO2 capture + Sabatier[/td]

[td]Requires ~30,000 m² solar array.[/td]

[/tr]

[tr]

[td]If Only O2 Produced on Mars[/td]

[td]0 tons[/td]

[td]0 tons[/td]

[td]Methane imported from Earth; drastically reduces ISRU load.[/td]

[/tr]

[tr]

[td]Life Support Water (Non‑Propellant)[/td]

[td]~0.6 kg/h/person[/td]

[td]N/A[/td]

[td]Separate from propellant production.[/td]

[/tr]

[tr]

[td]Atmospheric Source[/td]

[td]Subsurface ice mining[/td]

[td]Martian atmosphere (95% CO2)[/td]

[td]Atmosphere is thin, requiring high-volume intake.[/td]

[/tr]

[/table]Table: Mass Requirements to Fully Refuel a Starship on Mars (ISRU)

Category

Water Required

CO₂ Required

Notes

Baseline ISRU Requirement

540–600 metric tons

600–700 metric tons

Standard estimates for producing ~240–330 t CH₄ + ~960–1,000 t O₂.

Extended Range (Low–High)

500–1,000+ metric tons

540–900+ metric tons

Depends on efficiency, Sabatier conversion rate, and methane target mass.

Alternative Architecture (NASA DRA6)

~18 tons imported from Earth

0 tons (if methane imported)

Methane brought from Earth eliminates CO₂ processing.

Sabatier Stoichiometric Ratio

Water provides hydrogen; ~4 H₂ per CO₂ molecule

2.8 tons CO₂ per 1 ton CH₄

Producing 330 t CH₄ requires >900 t CO₂.

Propellant Output Supported

Enables production of ~1,200–1,500 t of propellant

Same

Full Mars–Earth return load.

Physical Volume Equivalent

~600 t = 9 m × 9 m × 9 m ice cube

N/A

Useful for visualizing mining scale.

Production Time

~2 years for full propellant load

~2 years

Based on typical ISPP plant assumptions.

Energy Requirement

Large-scale electrolysis + Sabatier

Large-scale CO₂ capture + Sabatier

Requires ~30,000 m² solar array (typical estimate).

If Only O₂ Produced on Mars

0 tons (no methane production)

0 tons

Methane imported from Earth; drastically reduces ISRU load.

Life Support Water (Non‑Propellant)

~0.6 kg/h/person without recycling

N/A

Separate from propellant production.

Atmospheric Source

Subsurface ice mining

Martian atmosphere (95% CO₂)

CO₂ is abundant but extremely thin, requiring high-volume intake.

Missing is the compression of the gasses outputted from Sabatier reaction as well as for the input co2 from Mars insitu use. Then to energy of cooling that must be done to recreate the liquid oxygen (LOX) + liquid methane (LCH4)

Of course we will get excesses that mayor not be saved depending on other factors.

Key Takeaways

1. Water and CO₂ requirements are of similar magnitude

Both fall in the 500–900 ton class for a fully fueled Starship return mission.

2. Water is the more “fixed” requirement

Because hydrogen must come from water, and methane production is hydrogen‑limited.

3. CO₂ requirements vary more widely

Because they scale directly with methane production targets and Sabatier efficiency.

4. Alternative architectures drastically change the numbers

Importing methane → CO₂ requirement drops to zero

Importing water (NASA DRA6) → only ~18 tons needed, but methane production still requires CO₂

5. The total propellant load (1,200–1,500 t) drives all upstream resource requirements

This is why the water and CO₂ numbers are so large.

The what is missing

You’re poking exactly where the hidden mass is in “30,000 m² of solar”—the thermodynamics. Let’s put rough-but-useful numbers on it.

High-level ballpark numbers per ton of CO₂ (Mars ISRU context)

Compression (Mars ambient → ~1 bar gas):

Roughly 40–80 kWh/ton CO₂ with realistic multi-stage compression and losses.

Cooling to near liquefaction temperature (~−56 °C to −78 °C):

Roughly 10–20 kWh/ton CO₂ (sensible + some subcooling margin).

Liquefaction (including refrigeration work at low temperature):

Roughly 80–150 kWh/ton CO₂ total (cooling + phase change + inefficiencies).

Total “Mars CO₂ capture + compression + liquefaction” (practical system):

Roughly 120–250 kWh/ton CO₂ depending on tech choice (mechanical compression vs adsorption, etc.).

These are engineering design numbers, not thermodynamic minima—they fold in realistic compressor/refrigeration efficiencies.

1. CO₂ compression from Mars atmosphere

Assumptions

Mars ambient pressure: ~600 Pa (~0.006 bar)

Target pressure for storage/reaction: ~1–10 bar (gas phase)

Process: Multi‑stage compression with intercooling.

Energy estimate

Ideal isothermal compression from 0.006 bar to 1 bar is only a few kWh/ton CO₂, but real systems are far from ideal.

Studies of Mars atmosphere acquisition and compression for ISRU typically land in the tens of kWh/ton CO₂ once you include:

Multi‑stage compressors

Motor and mechanical losses

Pressure drops and non‑ideal gas behavior

Useful design range:

40–80 kWh/ton CO₂ for compression to a few bar.

2. Cooling CO₂ to near liquefaction temperature

Context

After compression, CO₂ must be cooled from roughly ambient Mars temperature (say −50 °C) down to near its liquefaction region (around −56 °C at 5.2 bar, or colder at lower pressures).

Energy estimate

Sensible cooling load is modest (Mars is already cold), but:

You still need active refrigeration to control temperature and reject heat.

Real systems have COP < 1 at low temperatures.

Useful design range:

10–20 kWh/ton CO₂ for cooling from intake conditions to near liquefaction temperature.

3. Liquefaction of CO₂

This is where the energy really spikes.

Components

Further cooling below the triple point (if operating at lower pressure).

Latent heat of vaporization/sublimation.

Refrigeration inefficiencies at low temperature.

Thermodynamic minima are on the order of tens of kWh/ton, but with realistic COPs and system losses, practical liquefaction plants (even on Earth) often land in the 80–150 kWh/ton CO₂ range. Mars ISRU concepts that liquefy CO₂ for storage or feedstock are generally in that same ballpark once you include all parasitics.

Useful design range:

80–150 kWh/ton CO₂ for full liquefaction (including refrigeration work).

4. Mars CO₂ capture systems (compression vs adsorption)

NASA’s Mars Atmospheric Capture and Gas Separation work looks heavily at adsorption/temperature‑swing and freezing/liquefaction as alternatives to brute‑force mechanical compression.

Mechanical compression route:

Intake → dust removal → multi‑stage compression → cooling → liquefaction.

Energy dominated by compression + refrigeration → ~120–250 kWh/ton CO₂ total.

Temperature‑swing adsorption route:

Uses diurnal temperature swings to help drive desorption.

Can offload some of the “compression work” into thermal cycling, reducing electrical power draw but increasing system mass/complexity.

For Starship‑class ISRU, most architecture studies still budget hundreds of kWh per ton of CO₂ processed when you include capture, compression, and liquefaction.

5. How this scales to a Starship refuel

Take your earlier CO₂ requirement:

CO₂ needed: ~600–900+ tons per Starship

Using a mid‑range ~180 kWh/ton CO₂ (capture + compression + liquefaction):

Total energy:

600 t × 180 kWh/t = 108,000 kWh

to

900 t × 180 kWh/t = 162,000 kWh

Spread over 2 years (~17,500 h):

Average power just for CO₂ handling:

~6–9 kW continuous per Starship only for CO₂ capture/compression/liquefaction, not counting:

Water mining and electrolysis

Sabatier reactor operation

Liquefaction of O₂ and CH₄

General base loads

When you add water processing, Sabatier, O₂/CH₄ liquefaction, and overheads, you quickly climb into the hundreds of kW regime—hence the tens of thousands of m² of solar in many studies.

Online

Like button can go here

#4 Today 14:58:52

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,430

Re: wiki Block 4 starship first mission propellant creation

Core electrolysis performance numbers

Modern PEM/alkaline electrolysers (system level, not just stack):

Electrical energy per kg H₂:

50–55 kWh/kg H₂ is a good practical design number (HHV‑based, including balance of plant).

Water consumption:

~9 kg of H₂O per 1 kg H₂ (stoichiometric, plus a bit of overhead).

So for quick back‑of‑the‑envelope:

1 kg H₂ → ~50 kWh and ~9 kg water

How much H₂ do you need for a Starship refuel?

Take a representative “full” Mars refuel case:

Methane load: ~240–330 t CH₄

Hydrogen is 25% of CH₄ by mass, so:

For 240 t CH₄ → ~60 t H₂

For 330 t CH₄ → ~82.5 t H₂

Use 60–80 t H₂ as a working range.

Electrical energy for electrolysis:

At 50 kWh/kg H₂:

60,000 kg H₂ → 3,000,000 kWh (3 GWh)

80,000 kg H₂ → 4,000,000 kWh (4 GWh)

Average power over a 2‑year production window

Assume you give yourself 2 years (~17,500 hours) to refuel one Starship:

3–4 GWh over 17,500 h → ~170–230 kW average

That’s just for electrolysis, not counting:

CO₂ capture/compression/liquefaction

Sabatier reactor operation

O₂ and CH₄ liquefaction

Base/hab loads

If your earlier CO₂ + liquefaction + Sabatier + cryo budget is already, say, 200–300 kW, then:

Total ISRU plant power ends up in the 400–600 kW class per Starship if you want a 2‑year turnaround.

Solar array sizing impact

On Mars, a common rough design number is:

Average usable power per m² of solar (fixed, with losses): ~100–150 W/m² peak → 30–50 W/m² average over the day/year after dust, angle, etc.

If you need ~200 kW just for electrolysis:

At 40 W/m² average →

200,000 W / 40 W/m² = 5,000 m²

So electrolysis alone wants on the order of 5,000 m² of panels.

If total ISRU (all processes) is ~500 kW average:

500,000 W / 40 W/m² ≈ 12,500 m²

Which is nicely in the same ballpark as the “tens of thousands of m²” figures you see in Mars ISRU studies.

Electrolyser equipment mass

Ground/industrial PEM systems today:

Specific mass: often 3–10 kg/kW at the system level (stack + BoP) for containerized units.

For a Mars‑hardened, more conservative design, it’s reasonable to budget:

10–20 kg/kW at the system level (radiators, redundancy, structure, etc.)

So for ~200 kW of electrolysis capacity:

At 10 kg/kW → ~2,000 kg (2 t)

At 20 kg/kW → ~4,000 kg (4 t)

That’s a few tons of hardware per Starship‑scale ISRU plant just for electrolysis.

[table]

[tr][th]Item[/th][th]Value[/th][th]Notes[/th][/tr]

[tr]

[td]Electrolysis energy[/td]

[td]50–55 kWh/kg H2[/td]

[td]System-level PEM/alkaline, incl. BoP[/td]

[/tr]

[tr]

[td]Water per kg H2[/td]

[td]~9 kg H2O/kg H2[/td]

[td]Stoichiometric + small overhead[/td]

[/tr]

[tr]

[td]H2 needed for Starship[/td]

[td]60–80 t H2[/td]

[td]For 240–330 t CH4[/td]

[/tr]

[tr]

[td]Electrolysis energy total[/td]

[td]3–4 GWh[/td]

[td]Per full Starship refuel[/td]

[/tr]

[tr]

[td]Avg power over 2 years[/td]

[td]170–230 kW[/td]

[td]Electrolysis only[/td]

[/tr]

[tr]

[td]Solar area for electrolysis[/td]

[td]~5,000 m2[/td]

[td]Assuming ~40 W/m2 average[/td]

[/tr]

[tr]

[td]Electrolyser specific mass[/td]

[td]10–20 kg/kW[/td]

[td]Mars-hardened estimate[/td]

[/tr]

[tr]

[td]Electrolyser mass (200 kW)[/td]

[td]2–4 t[/td]

[td]Per Starship-scale ISRU plant[/td]

[/tr]

[/table]Turning CO2 into rocket fuel: Elon Musk’s radical plan to save Earth and reach Mars

Elon Musk wants to turn one of humanity’s biggest problems into the fuel for its boldest journey. Instead of treating carbon dioxide as waste, he is pushing SpaceX to capture CO2 and convert it into methane and oxygen, creating a closed loop that could both cut emissions and power rockets to Mars. It is an audacious attempt to align climate technology with interplanetary ambition, using the same chemistry to clean the sky above Earth and sustain life on the surface of Mars.

At the heart of this vision is a simple idea with complex engineering behind it: if rockets can run on propellant made from captured carbon, then every launch becomes a testbed for climate solutions as well as space exploration. The question I keep returning to is not whether the chemistry works, which scientists have already demonstrated, but whether Musk can scale it fast enough to matter for both Mars and the climate.

From Mars dream to carbon-neutral propellant loop

Elon Musk has been explicit for nearly two decades that his personal goal is to enable human exploration and settlement of Mars, and SpaceX has built its entire long term roadmap around that target. The company’s Mars colonization program is designed around Starship, a fully reusable vehicle that, according to Elon Musk, will eventually rely on propellant synthesized from carbon dioxide and water to create carbon neutral methane and oxygen. That same architecture, originally conceived for Mars, is now being reinterpreted as a way to turn atmospheric CO2 into fuel on Earth as well.In parallel, Musk has framed this fuel strategy as part of a broader climate agenda, arguing that rockets should not be exempt from decarbonization simply because they are a small slice of global emissions. Reporting on his push to use CO2 derived propellant notes that SpaceX is exploring technology to capture carbon from the air and convert it into methane, with the goal of supporting constantly affordable spacecraft capabilities that do not depend on fossil gas. That ambition is reflected in plans described in How SpaceX intends to convert atmospheric CO2 into rocket fuel, which would effectively turn the company’s Mars chemistry into a terrestrial climate tool.

The chemistry: Sabatier, electrolysis and “perfect fuel” methane

The technical backbone of Musk’s plan is a century old reaction that suddenly looks tailor made for Mars. The Sabatier process combines carbon dioxide with hydrogen to produce methane and water, and SpaceX has studied a Sabatier and water electrolysis system that would sit at the heart of a Mars base. In that scheme, water is split into hydrogen and oxygen, the hydrogen reacts with Martian CO2 to form methane, and the oxygen is reserved for both oxidizer and life support, a flow described in detail in the Sabatier and Water Electrolysis Process schematic for a Single Starship. The same chemistry can be mirrored on Earth, with captured atmospheric CO2 feeding Sabatier reactors powered by renewable electricity.Scientists are now refining that basic recipe to make it more efficient and better suited to real missions. Researchers at the University of California have demonstrated a catalyst that bypasses the intermediate step of producing hydrogen gas and instead converts CO2 directly into methane with high selectivity, a method described in their work on making methane on Mars. Other teams of Scientists have created new ways to convert methane into rocket fuel on Mars, validating concepts that Elon Musk and other engineers at SpaceX had theorized, with early experiments on Scientists converting methane into usable propellant on Mars described as very promising.

Carbon capture as launchpad: from climate tech to Mars logistics

For Musk, carbon capture is not just a climate patch, it is a logistical necessity if Starship is ever going to operate at the cadence he imagines. Analyses of Starship’s fuel demand point out that using conventional natural gas could nearly triple United States gas consumption for spaceflight, which is why some energy analysts have focused on how captured CO2 could be turned into methane at scale. One assessment of Starship’s methane supply notes that projects like Occidental’s plan to strip carbon from the air at roughly 200 dollars per kilogram of captured CO2 could feed into synthetic fuel production, a link drawn in a study of You Don and Have To Worry About Emissions From Mars Rocket The. That same analysis argues that if the methane is made from captured carbon, the net emissions from launches can be dramatically reduced.Musk has also tried to push the broader carbon capture field forward by dangling money and missions. Tesla CEO Elon Musk launched a 100 million dollar prize for carbon removal and has signaled that SpaceX will be an early customer for any technology that can pull CO2 from the atmosphere cheaply enough to turn into fuel, a commitment described in coverage of his plan to Launch Carbon Capture and convert it to rocket propellant. In a separate announcement, The CEO took to social media to say that SpaceX is initiating a program to take CO2 from the atmosphere and transform it into rocket fuel, a pledge captured in video of The CEO outlining the initiative. I see that as a signal that the company wants to be both a buyer and a developer of carbon capture hardware, using its own launch pads as demonstration sites.

Building the Mars refueling network: from Gigabay to 2026 Starships

On the ground, SpaceX is racing to build the industrial backbone that would make this fuel loop more than a lab experiment. The company has begun site preparations for Gigabay in Florida, with construction targeted to finish so the facility can support a higher launch rate via rapid reusability, according to a recent update on the Site at Gigabay in Florida. That kind of high cadence launch complex is exactly where on site CO2 to methane plants could make economic sense, since every Starship flight would draw from the same synthetic fuel infrastructure.In parallel, SpaceX is still publicly targeting its first dedicated Mars missions with Starships around 2026, with company materials describing plans to send the first Starships to Mars to gather critical data on entry, descent and landing and to begin scouting for resources. The official Mars page notes that these Mars Starships will be the pathfinders for later cargo and crew flights. Independent analysts have suggested that 2026 could be a turning point for Starship, with commentary on its “insane” goals arguing that this is the year it finally sheds the experimental label and begins to look like an operational system, a view reflected in breakdowns of Starship milestones.

Inside the Mars fuel factory: Sabatier plants, membranes and return tickets

Once Starship actually lands on Mars, the fuel story becomes existential. Space settlement advocates have long argued that early missions to Mars, including Robert Zubrin’s Mars Direct architecture, will require propellant production on the surface to make a return trip viable, and they point out that Starship uses methane for fuel precisely because it can be made from Martian CO2 and ice. Detailed studies of Propellant production on Mars describe how Early missions under Mars Direct would deploy reactors and compressors before crews arrive, so that tanks of methane and oxygen are waiting when astronauts step off the lander. Aerospace engineers have warned that sending humans without stored propellant would be reckless, arguing that the basic premise is to have fuel made in situ and fed back into the loop, a point underscored in analyses that note, “But the alternative, sending humans without propellant ready, is unacceptable,” as captured in But the discussion of SpaceX’s Mars plan.

Online

Like button can go here

#5 Today 14:59:45

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,430

Re: wiki Block 4 starship first mission propellant creation

Elon Musk Wants SpaceX to Reach Mars Using Carbon Capture. Here’s How It Could Work

A membrane Sabatier system for water recovery and rocket propellant production ABSTRACT

Gee he is reading our pages....

https://marspedia.org/Sabatier/Water_El … is_ProcessScientists create new way to convert methane into rocket fuel on Mars

No, You Don’t Have To Worry About Emissions From SpaceX’s Mars Rocket

Methane in the Form of Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) Will Power the Next Generation of Rockets

Elon Musk to Launch Carbon Capture Technology

yes another curtosocy of Mars society

Propellant production on MarsElon Musk announces SpaceX launching new program to use CO2 from atmosphere as rocket fuel Video

Break it! Elon Musk's SpaceX Insane Secret Starship Goals in 2026 Shocked NASA... Video

Here is the But A Closer Look at SpaceX's Mars Plan

Online

Like button can go here