New Mars Forums

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

Announcement

Pages: 1

#1 2026-02-04 18:44:35

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,395

Block 3 starship first mission

The information on the web indicates that 4 cargo with 2 crewed are thought to be there with fuel to return already waiting but that means those ships needed a dedicated mission to create fuel.

It might look like this with the ships on mars surface.

But what if the mission was a half payload delivery where man setup a system from the cargo and ships that they arrive in.

Ai indicates that

[center][size=150]Starship Block 3 – Fuel Remaining on Mars (50 t Payload)[/size][/center]

Scenario: Block 3 Starship is fully refueled in LEO (≈1200–1250 t propellant) and departs for Mars carrying 50 t of payload.

With a lighter payload than the “maxed out” case, Starship needs slightly less Δv from its tanks, so it arrives with a bit more residual propellant margin—but it still lands effectively “dry” from an operational standpoint.

[hr]

[size=120]Propellant Usage Breakdown (50 t Payload)[/size]

Trans-Mars Injection (TMI): ~850–900 t

Course Corrections: ~10–20 t

Mars EDL + Landing Burn: ~80–120 t

Total Used: ~940–1,040 t

Initial Load: ~1200–1250 t[hr]

[size=120]Estimated Remaining Propellant on Mars[/size]

Remaining = 1200–1250 t - (940–1040 t) Remaining ≈ 160–310 t (in main tanks, gross)However, this “remaining” is not clean, usable ascent propellant:

Main tanks: Largely reserved as performance margin, residuals, and non-usable slosh.

Header tanks: Provide the controlled landing propellant and are nearly empty after touchdown.

Practical, controllable post-landing propellant:

[size=120]Still only a few percent of total capacity, effectively negligible for ascent.[/size]The lighter payload improves margin and robustness, not the fundamental architecture: Starship is still intended to rely on ISRU for any departure from Mars.

[hr]

[size=120]Operational Conclusion (50 t Payload Case)[/size]

Starship lands with more margin than a heavier-payload mission, but still not enough for ascent.

Mission design still assumes full ISRU refueling (~1200 t CH₄/LOX) on Mars for return.

For base planning, you should continue to treat each landed Starship as operationally “empty”.

[center]Even with only 50 t of payload, Starship’s Mars architecture is still: arrive nearly dry, refuel on the surface.[/center]

Seems like something is off as a full payload is expected to be next to nothing but with less payload it should be quite a bit remaining.

Seems that AI gets confused....

Why “Less Payload” Doesn’t Automatically Mean “More Fuel Left on Mars”

1. The landing burn dominates the fuel budget — not the payload mass

On Mars, Starship performs:A long supersonic retro propulsive deceleration

A flip maneuver

A final landing burn

These burns require a minimum fixed amount of delta‑V, regardless of payload.

Even if you remove 50 tons of cargo, the landing sequence still costs almost the same amount of propellant.Payload mass changes the burn slightly, but not enough to leave a meaningful surplus.

Think of it like braking a car from 80 mph to 0 mph — removing passengers doesn’t change the braking distance much.

2. Starship uses header tanks for landing — and they are sized for safety, not efficiency

The landing fuel comes from:CH₄ header tank

LOX header tank

These tanks are:

Small

Fixed‑volume

Filled before EDL

Designed to guarantee a safe landing even in worst‑case conditions

If payload is lighter, the header tanks don’t magically shrink or adjust.

They still contain the same amount of fuel, and Starship still burns most of it to land safely.So the “extra” fuel isn’t in the main tanks — it’s in the header tanks, and it gets used anyway.

3. Mars atmosphere is thin — so payload mass barely affects drag

On Earth, a lighter vehicle slows down more easily.

On Mars, the atmosphere is so thin that drag is weak, so mass doesn’t change the deceleration profile much.Starship still needs nearly the same:

Heat shield performance

Retropropulsive braking

Landing thrust

Thus, fuel savings from reduced payload are tiny.

4. The landing burn must maintain a minimum thrust level

Raptor engines cannot throttle arbitrarily low.

Even if the ship is lighter:The engines must stay above minimum throttle

That means extra thrust

Which means extra fuel burned

This cancels out much of the theoretical savings from reduced mass.

5. Propellant gauging in low gravity is inaccurate

As we discussed earlier:Slosh

Low gravity

Thermal gradients

Pressure transients

All cause fuel readings to fluctuate, making it look like payload changes fuel remaining when it’s really just sensor noise.

The short version

Reducing payload does help a little, but Starship’s Mars landing fuel requirement is dominated by:Fixed landing maneuvers

Header tank sizing

Minimum engine throttle

Weak atmospheric drag

So the leftover fuel doesn’t scale with payload the way intuition suggests.

Offline

Like button can go here

#2 2026-02-04 19:05:59

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,395

Re: Block 3 starship first mission

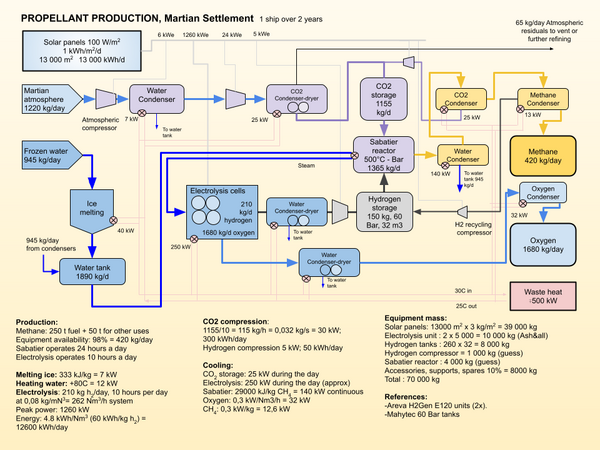

This is what Mars Society has in its planning

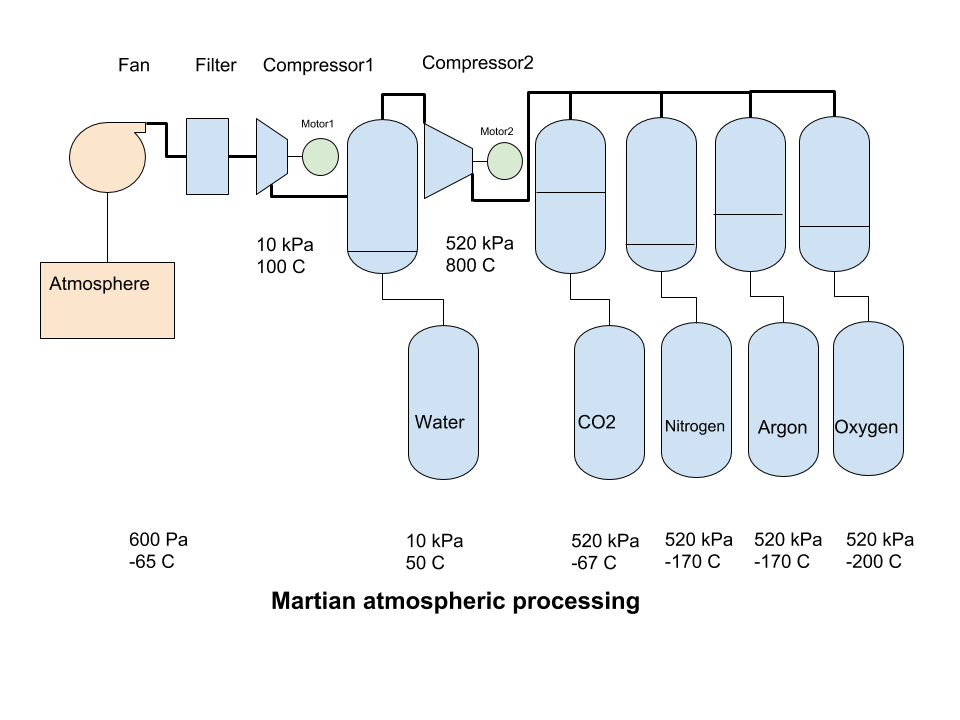

what we know for harvesting the atmosphere

Offline

Like button can go here

#3 2026-02-04 19:22:12

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,395

Re: Block 3 starship first mission

Our engineered atmosphere is 0.5 bar for internal use starting from mars air which is 0.006 bar Composition: 95% CO2, 2.85% Nitrogen, 0.17% Oxygen.

Normal earth air is o2 at 21% for 1.0 bar containing N2 which makes up almost the remaining % of the 14.7 psi.

Of course one of the issues is the quantity of air we need to the volumes that we are living with in and the other is the fuel levels to get back home are huge which makes the power demand high.

Offline

Like button can go here

#4 Yesterday 19:59:24

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,395

Re: Block 3 starship first mission

Missions that proceed must be able to produce propellant:

Establishing a Mars propellant plant to refuel a Starship for a return trip likely requires several cargo missions, with estimates suggesting 2 to 6+ ships to deliver necessary infrastructure (solar panels, mining equipment) and initial fuel stocks. While some scenarios suggest 3-4 ships can enable a return via in-situ resource utilization (ISRU), initial, safer approaches might use 6+ tankers to establish necessary infrastructure.

Infrastructure Requirements: A fully operational plant capable of producing 1,000+ tons of propellant (methane and oxygen) for a return journey requires substantial power, estimated at 5 GWh, needing ~250 metric tons of equipment, equivalent to 2+ fully loaded cargo Starships.

Fuel Mining & Production: The process involves extracting water ice and capturing \(CO_{2}\) from the atmosphere.

Alternative/Interim Methods: Rather than immediate, full ISRU, early missions might rely on landing 3-4 Starships, where 3 are drained to fuel 1 for the return trip, or using 4-6 ships to establish a rudimentary plant.

Scale: SpaceX aims to send at least 2 uncrewed cargo ships before the first crewed mission to set up power, mining, and life support. Ultimately, the number of ships depends on the efficiency of the ISRU plant, the power capacity installed, and the willingness to risk the first crew's return capability

Water source from Korolev Crater or other location would be of benefit to getting a good start.

Based on current SpaceX Mars mission architecture, establishing a propellant plant on Mars to refuel a Starship for a return journey, utilizing water ice, requires a multi-stage, cargo-heavy operation. Initial Setup Phase: To establish the necessary propellant plant (Sabatier reactors, mining equipment, solar arrays) at a location like Korolev Crater, early, uncrewed missions would need to land several cargo Starships (potentially 2–5) containing roughly 100+ tons of equipment each.Propellant Production Requirement: To refuel a single Starship for a return journey, the plant must produce approximately 1,200 metric tons of propellant (methane and oxygen).Operational

Requirement: While early estimates suggested 1–2 cargo ships worth of equipment could start production, a more robust and faster turnaround (within one synod, or 26 months) likely requires at least 3-4 cargo ships to be active to ensure enough power and water processing capability to produce the ~1,200+ tons of fuel. In summary, to start a plant, 2-5 dedicated cargo Starships are required to land the equipment, with at least 3-4 of them acting as operational plant components/fuel depots to reliably produce enough fuel for one return trip.

Key considerations: Water Source: Korolev Crater is an ideal, high-latitude location (\(73^{\circ }\text{N}\)) with large, accessible, near-surface water ice deposits, reducing the need for deep drilling.

Power: The limiting factor will be the mass of solar panels or nuclear reactors required to power the electrolysis process to turn that water into hydrogen, requiring significant cargo mass for power generation.

Launch Windows: These cargo ships must arrive at least one, if not two, synodic periods (26–52 months) before the crew arrives, to ensure the tanks are full

Offline

Like button can go here

Pages: 1