New Mars Forums

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

Announcement

#51 2026-01-25 17:45:41

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,348

Re: Why Artemis is “better” than Apollo.

Offline

Like button can go here

#52 2026-01-26 10:15:28

- GW Johnson

- Member

- From: McGregor, Texas USA

- Registered: 2011-12-04

- Posts: 6,131

- Website

Re: Why Artemis is “better” than Apollo.

Well, NASA managers are "playing the odds". Yes, the Artemis-2 heat shield is going to spall out chunks, maybe more of them since it was built less permeable, or so the story says. The Artemis-1 heat shield was mostly identical, and spalled out chunks. But those ugly and alarming craters left behind were not enough to cause a burn through.

Less likely would be two craters close enough together to be one big crater, at the bottom of which another chunk happens to spall out! That would penetrate most of the way through the heat shield, leading to a burn-through, in turn very likely fatal for the crew.

You have to understand what Avcoat really is. It is a cycolac polymer loaded with little microballoons to lower its density and increase its ablation rate. Denser is lower ablation rate. Too dense, and gas has more difficulty getting out of the less permeable char. But the more filled with microballoons, the more viscous it is, and hard to mold into where you want it to go. Artemis 2 has fewer microballoons in more of the tiles they made, according to the story. That's denser, with a slower ablation rate, but a less permeable char, increasing the risk of the gas not getting out, and so causing chunks to spall off.

Their theory is that gas unable to get out fast enough blows off chinks of char, exposing virgin material beneath too soon. That’s probably right. Probably.

Have you ever handled real charcoal? Not the pressed crap they sell for your grill, but an actual charred piece of wood? Depending upon the species, it can be quite weak. The more fibrous and stronger the virgin wood, if the charred fibers hold together, the physically tougher a charred piece of it is. Think of oak as strong char (good coals in the fireplace), versus mesquite as weak (doesn't even form coals, just burns immediately to soft ash).

The fundamental mistake NASA made with the Orion heat shield has NEVER BEEN ADDRESSED! That was deleting the fiberglass hex from the Avcoat! They continue to think of that as an either/or decision. Either we build it like Apollo, or we make tiles. That is just plain BS !!!!

You can put the hex back into every tile you make, where as the hex chars and melts, but at a rate slower than the cycolac, its fibrous structure ties the cycolac char together, as a sort of composite material. THAT is why the heat shields built Apollo-style did not spall chunks! THAT is the real difference! Not piddling around with more or less microballoon content in the cycolac polymer!

Here is where you have to see beyond the either/or thinking, in order to put the hex back into the Avcoat. Apollo (and EFT-1 Orion) had the hex bonded to the capsule structure. Into each and every hex cell, you had to manually gun viscously-stiff cycolac with a high microballoon content, to make sure its ablation rate was faster than the fiberglass hex (likely epoxy or vinyl ester resin on glass fiber, I don't know such details). There were 300,000-ish cells on Apollo, and nearly 400,000 such cells on Orion EFT-1. That's a LOT of manual labor to be paid!

Managers do not like to spend money. The good ones will spend what it takes to protect lives. The bad ones will not. There are more bad ones than good ones, we’ve already seen that during 2 shuttle-loss inquests. In fact, the good ones might well now be extinct, near as I can tell.

Here is how you do it OUTSIDE their either/or thinking:

Put a hex core into a tile mold with no bottom. Instead of pouring your cycolac /microballoon mix into an empty mold with a bottom, put that hex-containing bottomless mold on the outlet of an extrusion press (such are very common in the molded plastics industry). Load your cycolac / microballoon mix into the press, and extrude it through the cells in the hex inside that bottomless mold. Use a trowel to scrape most but not all of the extruded strings of mix off the bottom of the hex, and install the bottom of the mold. Then remove the mold from the press, add a bit more mix on top with the trowel, and install the top of the mold. Go cure the thing.

Result: hex-reinforced tiles that will not spall, because they are fiber-reinforced AND you used the correct high-microballoon mix ratio to get the correct ablation-rate ratio! AND you did it with low labor, saving scads of money! The labor relates to a few dozen tiles, not a third of a million cells. But you filled a third of a million cells doing it this way!

I gave that notion free of charge to NASA long ago. I was able to confirm that their heat shield group in Houston actually got it, and that some folks in that group thought very well of it. Then I never heard another word from anybody at NASA about it.

Meanwhile, NASA has had the 2 years necessary to make tiles that way and confirm that the process actually works. But they DID NOT DO THAT! They instead spent all their time and money trying to make unreinforced tiles look OK by analysis, while ONLY considering the hand-gunned Apollo process as the alternative!

Either/or thinking among top managers. The very same as what killed 2 shuttle crews! They so very clearly do NOT listen to their own engineers, much less engineers from outside the agency!

And THAT, sadly, is my assessment of NASA, regardless of who leads it!

GW

GW Johnson

McGregor, Texas

"There is nothing as expensive as a dead crew, especially one dead from a bad management decision"

Offline

Like button can go here

#53 2026-01-26 12:24:51

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,348

Re: Why Artemis is “better” than Apollo.

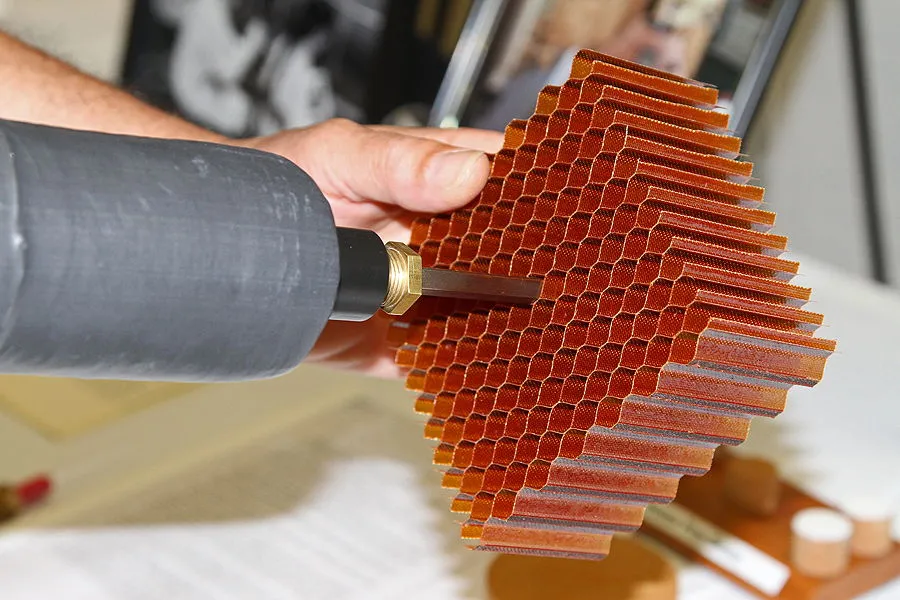

Photos: NASA's Orion Spacecraft Heat Shield on Display

For the manual filling.

Offline

Like button can go here

#54 2026-01-29 10:48:26

- GW Johnson

- Member

- From: McGregor, Texas USA

- Registered: 2011-12-04

- Posts: 6,131

- Website

Re: Why Artemis is “better” than Apollo.

Based on the color in Spacenut's photo, the resin in the hex may be phenolic. The fiber definitely looks like glass, but could be a mineral fiber like fire curtain cloth, although that's not likely due to the high costs compared to glass.

I've never seen anything definitive about those material choices, so I do not know.

But look at Spacenut's photo once again! That's a chunk of the hex held in the hand, to show how the gun nozzle fits the hex cell, for hand-gunning the heat shield. It also shows almost EXACTLY my alternative!

Put a bottomless mold around that chunk of hex, and attach it to the outlet of a plastic extrusion press. Use the press to fill all the cells in the hex at once, plus the border between hex and mold wall. Trowel off the excess on the bottom, install the mold bottom, take the mold off the press, trowel some of that excess onto the top, and install the mold top. Then go cure the thing.

You have to think outside the either/or trap! They've spent 2 years now trying to justify-with-analysis flying a defective heat shield with a crew! They could have replaced that heat shield with a hand-gunned one in that 2 years, or they could have tried my idea and proven it worked in that 2 years, with the hand-gunned option as a backup.

THEY DID NEITHER!

They did not want to pay the labor to hand-gun any more heat shields, and I cannot fault that aversion. But they did NOT value crew safety high enough to NOT fly a known defective heat shield! And, they were too bound up in their either/or thinking to consider any other options! Not to mention "not invented here" thinking, since my idea came from outside their organization. (I had to use a friend at NASA just to get it inside!)

Either/or thinking and "not invented here" attitude. Not prioritizing crew safety above cost and schedule! THAT is the fault here! And it has NOT changed since Challenger and Columbia! The real lessons of those disasters were quite apparently NEVER learned!

Those shuttle loss inquests were around a billion dollars, and 18 months or more, each! There really is nothing as expensive as a dead crew! Especially crews dead from bad management decisions! Just like my by-line says!

GW

Last edited by GW Johnson (2026-01-29 10:49:00)

GW Johnson

McGregor, Texas

"There is nothing as expensive as a dead crew, especially one dead from a bad management decision"

Offline

Like button can go here

#55 2026-01-29 18:55:30

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,348

Re: Why Artemis is “better” than Apollo.

NASA scrambles as Orion’s heat shield glitch forces a total reentry rethink

NASA’s return to crewed lunar flight is now hinging on a slab of material at the bottom of Orion that did not behave the way engineers expected. Instead of a straightforward fix, the agency is reworking how the capsule will slice back through Earth’s atmosphere, a late-stage pivot that has scrambled planning for Artemis II and beyond. The stakes are blunt: four astronauts, a 50-year gap in human lunar voyages, and a heat shield that has already surprised its designers once.

What began as an engineering anomaly on an uncrewed test has grown into a full campaign to rethink reentry, timelines, and risk tolerance. The result is a program that is still moving toward the Moon, but now with a visibly more cautious and contested path to getting its crew home alive.

The anomaly that turned a test flight into a warning shot

The trouble started when the first integrated Artemis flight, Artemis I, sent The Orion around the Moon and back to Earth as a high energy test of the Space Launch System and Orion and associated systems. As Orion slammed into the atmosphere at 25,000 miles per hour, or 40,200 kilometers per hour, the capsule’s ablative material did not erode in the smooth, predictable way models had forecast. Instead, chunks of the Avcoat coating came off in a pattern that suggested gases failed to vent properly and Pressure behavior inside the material was not fully understood, turning what should have been a textbook demonstration into a red flag for future crews.In the months after the Orion spacecraft splashed down, NASA acknowledged that the base of the capsule had lost more of its protective layer than expected as it returned to Earth from the uncrewed Artemis 1 mission. Internal reviews and an external Audit Identifies Significant Issues with the Orion Heat Shield, documented by the agency’s OIG, flagged concerns such as bolt melting and the possibility that unexpected erosion paths could threaten the vehicle and loss of crew. Those findings pushed the heat shield from a routine certification item into the central technical risk for the entire Artemis campaign.

NASA’s investigation and the decision not to rebuild

NASA responded with a sprawling investigation that, according to agency leaders, involved more than 100 tests across the country to understand why Avcoat had behaved so differently in flight. After that test campaign, Nelson and other officials said the U.S. space agency was moving forward with Ori hardware for the next mission rather than tearing the system apart. The agency’s decision comes after an extensive internal review of the Artemis I heat shield issue showed the Artemis II heat shield configuration could be flown safely if the mission profile was adjusted, a conclusion that has become the backbone of the current strategy.Experts who briefed the public described how NASA, Orion program managers, and materials specialists dissected flight data, ground tests, and modeling to isolate the root cause. In parallel, a separate Jan briefing framed how Artemis and later Mars ambitions depend on getting this right, since the same family of materials and design philosophies will be needed for crewed Mars missions. Another Jan discussion of the real cause of the Orion heat shield behavior, tied directly to Artemis and NASA’s broader exploration roadmap, underscored that the agency believes it understands the physics well enough to proceed, but will change how the spacecraft comes home rather than rebuild the shield from scratch.

A reentry profile rewritten on the fly

Instead of replacing the heat shield on the already assembled Artemis II capsule, NASA is flying the spacecraft as-is and instead modifying the re-entry profile. That choice, described in a Dec update that noted Last week NASA announced the new approach, effectively trades hardware changes for trajectory and attitude tweaks that reduce peak heating and alter how loads are distributed across the Avcoat surface. The issue relates to a special coating applied to the bottom part of the spacecraft, called the heat shield, and the new plan is to manage how that coating is stressed rather than to redesign it this late in the flow.Further complicating the situation was the fact that by the time the anomaly was fully understood it was already too late to fix the heat shield for Artemis II without a major schedule reset, as a Jan analysis of the program noted. NASA’s Artemis II Orion heat shield is now at the center of an ongoing safety debate in the lead-up to Artemis II, with engineers planning a reentry that uses the Moon’s gravitational pull and a carefully shaped corridor through the atmosphere to keep conditions within the bounds of what the investigation says the system can tolerate. In practice, that means a total rethink of how Orion will descend, from entry angle to roll maneuvers, all aimed at ensuring the Avcoat never again surprises the people riding behind it.

Schedules slip, rockets roll, and the Moon stays in sight

The heat shield saga has rippled directly into timelines. In Dec, NASA is hitting a reset on its Artemis Moon schedule, with In April 2026 now targeted for launching a crew of four as part of the Artemis II mission on a 10 day circumlunar flight. A separate Dec update on NASA’s Artemis II mission, which aims to return humans to the Moon after a 50-year hiatus, confirmed that the flight had already been delayed from an earlier September 2025 target, illustrating how thermal protection concerns and other integration work have pushed the calendar to the right.Accordingly, a Dec briefing announced new target launch dates for its Artemis II crewed test flight and Artemis III crewed lunar landing, with Both missions shifted so that the landing now moves from 2026 to mid 2027. A related Dec overview of the SLS hardware highlighted how the Core stage, which holds two propellant tanks for Liquid oxygen and Liquid hydrogen, stacks into a Total height fully stacked of 322 feet, or 98 meters, underscoring the scale of the system that must work in lockstep with Orion’s revised reentry plan. Even as schedules move, the physical rocket is advancing: Jan imagery shows NASA’s Artemis II Space Launch System, or Artemis II Space Launch System, and Orion illuminated at Launch Complex 39B as teams prepare for a fueling test and a simulated countdown known as terminal count, while a separate Jan community piece noted that The Space Launch System, or SLS, was rolled out to Launch Pad 39B with John Saccenti describing how the vehicle is expected to support a launch window that opens next week on Feb. 6.

Astronauts, risk, and a public test of trust

Behind the engineering charts are four people who will strap into this vehicle. Jan social media posts from NASA framed the mission in aspirational terms, with Our Artemis II crew highlighted as heading to the Moon and a reel noting that @astro_reid, @astro_victor, @astro_christina, and the @canadianspaceagency’s @astrojeremy will fly the first crewed Orion. Another Jan update on NASA’s Artemis II mission stressed that NASA’s Artemis II mission, which aims to return humans to the Moon after a 50-year gap, is not just a symbolic milestone but a critical systems test that must prove the heat shield, life support, and navigation can all function together in deep space before any landing attempt.

How Artemis II’s free return path could save astronauts if everything fails

Artemis II is designed to carry humans around the Moon and back on a path that can bring them safely home even if their main engine never lights again. Instead of relying solely on propulsion, the mission leans on a carefully tuned “free return” loop that lets gravity do the work if everything else fails. I see that choice as the quiet centerpiece of NASA’s push to send people farther from Earth than any crew has ever gone in more than 50 years.

That backup path is not a bolt‑on contingency but a core part of how the flight is built, from launch through the swing behind the Moon and the plunge back into Earth’s atmosphere. It shapes the ten‑day timeline, the way Orion tests its systems, and even how far past the lunar far side the astronauts will travel before turning for home.

Why Artemis II needs a built‑in way home

Artemis II is the first crewed outing of the Artemis program, and it will send four astronauts on a roughly ten day loop around the Moon without landing. According to Artemis II mission descriptions, the flight is planned as a lunar spaceflight under the broader Artemis campaign led by NASA. It will be the first time humans travel toward the Moon since the Apollo program ended, and planning documents describe it as the first return of people to the lunar vicinity in over 50 years.That distance raises the stakes. The Artemis II crew will travel approximately 4,600 miles beyond the far side of the Moon, making it the farthest human spaceflight from Earth so far. With the Space Launch System rocket still relatively new, with only one full mission behind it, even supporters acknowledge that, as one analysis put it, Plus the rocket and its components do not yet have a deep flight record. In that context, a trajectory that can carry the crew home without further engine burns is not a luxury, it is a risk‑reduction tool.

How a lunar free return actually works

The free return concept is simple to describe and fiendishly complex to design. Mission planners set Orion on a path where, as it swings behind the Moon, the spacecraft falls into the grip of lunar gravity and then naturally arcs back toward Earth without needing another major burn. One explanation of the physics puts it this way: Here, as Orion approaches our lunar neighbor, the Moon’s immense gravity takes over and bends the track into a loop that guarantees a safe return home if nothing else intervenes.Visualizations of the Artemis II Trajectory show the Nominal path of Artemis II from Earth orbit around the Moon and back. As Orion nears the far side, the trajectory is tuned so that the spacecraft’s momentum and the Moon’s pull combine to “slingshot” it home. Commentators in one spaceflight group describe this as a backup engine in its own right, noting that On February, Artemis II will rely on a route where the spacecraft will automatically slingshot them home if needed.

From launch to lunar swingby: threading the needle

The safety net only works if the early part of the mission hits its marks. On Day 1, mission plans describe Day 1 as Launch and Earth orbit, with the rocket climbing through the atmosphere and, As the ascent continues, shedding its solid boosters and protective hardware. A major change from the uncrewed Artemis I flight is that the second mission will not enter a long lunar orbit but will instead approach and back away on a tighter loop, as outlined in comparisons of the two missions.On Day 2, while still flying around Earth, the crew will run Systems checks and a departure burn while Orion is still close enough for quick troubleshooting. That burn is what actually commits the spacecraft to the translunar trajectory. Flight dynamics specialists have published detailed work on optimized trajectory correction burns for NASA Artemis II mission, showing how small midcourse tweaks keep the path aligned with the free return corridor. Once those are complete, the crew is effectively riding a gravitational rail toward the Moon.

Why Artemis II will not orbit the Moon like Apollo 8

One of the most striking differences between Artemis II and its Apollo predecessors is that it will not brake into lunar orbit. As one mission manager put it when comparing the flights, Apollo 8 actually went into lunar orbit, did 10 revolutions and then came home, while Artemis II is not actually going into lunar orbit at all. That choice is deliberate. By skipping the braking burn that would capture Orion around the Moon, the mission avoids a point of no return where a failed engine firing could leave the crew stranded.Some enthusiasts have debated how closely Artemis II mirrors the Apollo era. One widely shared comment, attributed to JimEd Howland False, notes that Only Apollo 8, 10 and 11 used a free return trajectory before firing their main engine to get into lunar orbit. Artemis II, by contrast, is built so that the free return is not just a starting condition but the entire shape of the flight. That means the crew will still see the far side and travel thousands of miles beyond it, but they will always be on a path that naturally bends back toward Earth.

When everything fails: the “backup engine” of gravity

The real test of the free return design is what happens if something goes badly wrong. Mission briefings emphasize that Artemis II will return to Earth using what is called a lunar free return trajectory, which allows the astronauts to get back even in the event of engine failure. Another technical overview notes that The Artemis II mission will use a similar free return path precisely to provide that safety margin in the event of an engine failure. In other words, if Orion’s main engine refused to fire after the outbound burn, the spacecraft would still loop behind the Moon and head home.Fans of the program have seized on that feature as the most remarkable part of the mission. One viral post framed it this way: On February 6th the Artemis II mission will launch, but the most interesting part is not the rocket, it is the route that acts as a built‑in rescue plan. Another discussion of the same idea stresses that But the route is the backup engine, a technique that was used by the Apollos and that will automatically slingshot them home if the hardware goes quiet.

Offline

Like button can go here

#56 Yesterday 02:22:37

- clark

- Member

- Registered: 2001-09-20

- Posts: 6,380

Re: Why Artemis is “better” than Apollo.

it will be a successful launch, and a very, very, anxious re-entry. if it was easy, SpaceX would have done it last year. cheers.

Offline

Like button can go here

#57 Yesterday 11:21:05

- GW Johnson

- Member

- From: McGregor, Texas USA

- Registered: 2011-12-04

- Posts: 6,131

- Website

Re: Why Artemis is “better” than Apollo.

Some of these reporters and press release writers are abysmally ignorant. The phrase "moon's immense gravity" in paragraph 5 of the second article quotation is proof enough of that.

Plus I noticed the real reason they will not orbit the moon was NOT given: SLS block 1 with Orion does not have the delta-vee capability to enter lunar orbit and get back out of it! Block 1B might, but that's not what this SLS is.

As for the heat shield, I have previously posted how they are making the same kinds of bad management decisions as killed 2 shuttle crews. It's been 2 years since Artemis 1 flew. They have had the time to have replaced the heat shield, despite the article claiming there was not enough time. They spent that 2 years trying to analytically show changing entry trajectory was enough safety margin, and not everybody inside (or outside) NASA agrees with that.

Once again we see schedules and budgets prioritized above crew safety, while either/or thinking and "not invented here" attitude prevented looking for a third alternative besides flying flawed or doing it with the expensive Apollo method.

GW

GW Johnson

McGregor, Texas

"There is nothing as expensive as a dead crew, especially one dead from a bad management decision"

Offline

Like button can go here