New Mars Forums

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

Announcement

#1 2025-10-26 18:04:47

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 8,413

Coal-fired Brayton Cycle Supercritical CO2 Boilers

Research Gate Link:

300 MW Boiler Design Study for Coal-fired Supercritical CO2 Brayton Cycle

Science Direct Link:

300MW boiler design study for coal-fired supercritical CO2 Brayton cycle

The ultimate source is Applied Thermal Engineering, Volume 135, 5 May 2018, Pages 66-73.

Abstract

Supercritical CO2 (S-CO2) Brayton power cycle has been considered as a promising alternative choice of conventional steam cycle for coal-fired power plants. A conceptual design of the boiler is conducted for a 300MW single reheated recompression S-CO2 Brayton cycle for coal-fired power plant with turbine inlet parameters of 32MPa/600°C/620°C. The conventional economizer (ECO) is replaced with the split heater (SH) to reduce the inlet temperature of cooling wall of the furnace as well as to recover the flue gas heat The technology adaption of S-CO2 power cycle for coal-fired power plant has been evaluated in terms of specific design of the 300MW coal fired boiler as well as the whole thermodynamic cycle layout. The boiler design and off-design thermal calculation results show that the S-CO2 boiler proposed in this paper can match well with the entire coal-fired S-CO2 Brayton cycle power generation system and has a good boiler variation performance.

As the linked design study seems to suggest, the thermal power density for coal-fired Brayton Cycle sCO2 could exceed 1,000MW/m^3. That's a pretty dramatic power density increase over existing steam boilers. The study was published in 2018, and makes the case that going to 700°C temperatures is not economic because it requires Nickel-based superalloys. However, more recent advances in materials, machining, and fabrication methods have already demonstrated cost-competitive superalloy solutions that outperform steam turbines on cost in SCO2 applications, due to the dramatic mass and volume reductions of the machinery involved. We've already begun fabricating SCO2 gas turbine components for SCO2 commercial electric power plants here in Texas, from those superalloys, and the most significant costs seem to be in finding qualified machine shops and welders with the expertise to machine or fabricate the components.

Very recently demonstrated 100X energy (thus fabrication cost) reductions associated with complex geometry RCC components could make superalloy cost and availability mostly irrelevant, except perhaps for printed circuit heat exchangers, piping, and seals. Using RCC, a power turbine and turbine casing's combined gravimetric power density could easily reach 200kW/kg for a multi-MW power turbine suitable for marine propulsion applications.

In previous posts scattered about the forum, I've put together a "system" for supplying bulk power to the United States, and potentially the entire world, without resorting to using either nuclear power of quantities of technology metals that don't presently exist to be used for all-electric energy generating and storage equipment. While I highly favor the use of nuclear technologies on account of their incredible power density and vanishingly small waste streams, relative to all competing alternatives, I have accepted that the combination of our political and economic climate has resulted in very little apparent appetite for multi-year reactor construction projects. I have also accepted that the materials math for photovoltaics and/or electric wind turbines, but especially electro-chemical batteries to provide enough fast storage for grid stability and seasonal energy availability variations, simply "doesn't math". I came to that conclusion some time ago and nothing I've seen since then has changed the math, so I discarded that as a reality-based solution. It was a good old-fashioned "college try".

As such, I then devoted hundreds of hours of study searching for viable alternatives to new-build nuclear reactors and the current generation of photovoltaics / electric wind turbines / electro-chemical batteries, which also have little hope of scaling-up to supply the majority of our energy demands over the next several decades, absent monumental increases in mining productivity across a host of technology metals. The specialty metals requirements of a 70% photovoltaics / electric wind turbines powered grid, when combined with mere weeks of energy storage, so as to truly supply the majority of our primary energy, without coal-fired steam turbines or natural gas turbines spinning at all times, is exactly where this "green energy" fantasy fails.

The proponents of this all-electric "solution", which at least outwardly appears to create more problems than it solves, are either hoping for game-changing technology advances and production at-scale at some indeterminate future date, or refuse to accept the ugly arithmetic of projected scale-up for mining output and specialty metals consumption per technology unit. The required quantities of poly-Silicon, Copper, and Aluminum vividly illustrates how far beyond present global annual mining output those technology metals requirements are, in order to implement their all-electric vision for the future. The metals requirements are measured in hundreds (Copper, Aluminum) or even thousands of years (rare Earths) of current global annual production capacity. While I would never claim that tech advances cannot overcome existing implementation hurdles, the number of hurdles and the scale of the mining output increases are grossly unrealistic using current or projected near-term technologies.

Most of these people think we will simply stop using stored chemical energy provided by hydrocarbon fuels, to deliver on-demand power, in favor of a variety of new technologies that are only feasible to use at the present time because they are back-stopped by stored fuels or, in some cases, nuclear energy. The transition process to achieve that might take another century before mostly displacing coal / natural gas / diesel / kerosene / gasoline fuels, since all potential successor technologies are still in their infancy. In the mean time, we're playing a dangerous game with money and technology by making "bets" we can't actually cover when something goes wrong. I think the complete grid failure in Spain demonstrated how far belief about the stability of an all-electric grid, predominantly powered by photovoltaics and electric wind turbines, which provide no grid-inertia, diverged from objective reality. Spain attempted to prove that they didn't require a "spinning reserve", which was provided by their small fleet of nuclear reactors. The only thing they actually proved, was that even during ideal generating conditions for the currently favored all-electric energy generating machines, Spain's grid was never stable. If conditions had been unfavorable, there could've been many more fatalities and a far greater loss of GDP. Thankfully, that didn't happen. Only circumstances made Spain's total grid failure a brief event with limited permanent damage. Spain doesn't have sufficient fast storage or spinning reserve, unless they keep operating their nuclear reactors. Shutting the reactors down was an ideological vs engineering-driven decision- one that didn't pay off.

For nations without nuclear power programs, the lowest cost "pay-as-you-go" bulk energy comes from coal or natural gas turbines. If money is plentiful, then extra funds can be invested into photovoltaics and/or electric wind turbines to opportunistically capture more energy. Provided that the cost increase to the rate payer is not substantial, there's nothing wrong with capturing additional energy that way. An issue arises only when the grid is reliant on those forms of energy, but insufficient stored energy exists as a backup. Nations such as Germany and Spain are already well past the point of sensibility in their energy mix, because they either can't or won't build adequate fast storage, likely due to cost. Everyone knew that an all-electric grid lives or dies on the basis of fast storage (electro-chemical batteries) availability to buffer supply-and-demand fluctuations. We're not going to do that at the scale / storage capacity required, due to total cost and materials scarcity. That means we need a viable alternative.

I think pure Carbon "synthetic coal" mixed into water to create a low-flammability pumpable slurry, synthesized from atmospheric or oceanic CO2 captured using solar thermal power, is that more viable alternative. Since we didn't dig this stuff out of the ground, we're adding nothing to the atmosphere by using and recycling it. High-purity captured CO2 also has many uses beyond serving as a fuel feedstock. Thanks to some new / novel room-temperature liquid metals, such as Gallium-Indium-Tin and Gallium-Indium-Copper eutectic mixtures, we have discovered a way to convert atmospheric CO2 back into pure Carbon without any electrical or thermal energy beyond the power necessary to circulate / "bubble" the CO2 through the column of liquid metal. The pure Carbon "floats" on top of the metal, so extracting it is pretty easy to do. The metal catalysts also appear to be remarkably stable over hundreds of hours of operation. That means we could use them to strip Carbon from CO2, at room temperature, to create chemical energy reserves without mining for coal or drilling for oil and gas. The lower calorific content of a pure Carbon fuel, as compared to fuels containing Hydrogen, can be partially offset by using higher temperatures in conjunction with Supercritical CO2 gas turbines.

The exhaust product of a power plant consuming pure Carbon and O2 from a synthesis plant, is essentially pure CO2 mixed with some residual water vapor, so it can be more easily captured at the plant and re-compressed into LCO2 for shipment back to a Carbon / O2 synthesis plant. The most undesirable emissions from burning mined coal- heavy metals, fly ash, NOx, and SOx, are reduced to almost nothing by using synthesized pure carbon. We re-capturing most of the CO2 at the generating plant so we don't have to re-capture it from the atmosphere at greater energy cost. The development of supersonic CO2 compressors makes that re-capture step practical, as it consumes less than 10% of the plant's gross output, unlike traditional multi-stage CO2 compressors.

SCO2 gas turbines, supersonic CO2 compressors, and SCO2 "boilers" have all been developed over the past 25 years, in a concerted effort to meaningfully improve the thermal-to-electrical efficiency of coal and natural gas power plants. The most consistent themes throughout SCO2 technology development have been successful technology demonstrations and incredible power density, to the point of becoming a more thermally efficient successor to conventional gas turbines and geared steam turbines.

The two major reasons for switching from geared steam turbines to gas turbines for commercial electric power generation and marine propulsion were far too much space claim associated with steam power plant and improved thermal efficiency / fuel consumption reduction. SCO2 gas turbines manage to improve upon the power density, startup times, and thermal efficiency of conventional marine gas turbines, which is why we need to pursue these new turbine-based solutions, if we're eventually going to have any meaningful energy transition to natural energy.

We're not short-of-supply of coal / oil / gas at the present time, but the existing reserves won't last forever. Eventually we'll have to synthesize our own fuels, if only for backup power or power at night, and we'll want more efficient plants to use them with. It's better to start that process now while we're still moderately energy-rich and capital-rich.

We need solar thermal to deliver bulk energy in the form it's already consumed in, we need new generation power plants that can supply on-demand energy, and we need fuel synthesis so that we never run out. We're not going to create enough all-electric machines in the span of a few short decades to matter much, if only because we lack the metals to do so. We do have sufficient supplies of metals for the types of machines I've spilled so much ink describing, to continue generating electric and thermal power from centralized locations.

Offline

Like button can go here

#2 2025-10-26 18:40:02

- Calliban

- Member

- From: Northern England, UK

- Registered: 2019-08-18

- Posts: 4,279

Re: Coal-fired Brayton Cycle Supercritical CO2 Boilers

Quite a lot to read through here, so I will comment again when I've had chance to read it all. Gas turbine blades have always been made from high temperature nickel alloys. Since the 90s, they have been grown as single crystals with mineral rods embedded to provide cooling channels by dissolving the rods in weak acid after casting. So I'm not sure why the reference suggests that using nickel alloys is impractical or expensive. It is standard aerospace practice. Take any COTS GT and you find nickel alloy components. For non-moving parts, steels can still be used at 700°C. Strength will be reduced substantially and corrosion in hot CO2 will be more of a problem. But is can be done. There are specialist oxide dispersion strengthened mechanical alloys that were specifically developed for operation in this temperature range.

"Plan and prepare for every possibility, and you will never act. It is nobler to have courage as we stumble into half the things we fear than to analyse every possible obstacle and begin nothing. Great things are achieved by embracing great dangers."

Offline

Like button can go here

#3 Yesterday 10:12:00

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 23,777

Re: Coal-fired Brayton Cycle Supercritical CO2 Boilers

This post is to remind readers of the collection of information about supercritical CO2 at Wikipedia...

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Supercrit … on_dioxide

The article was last updated in November of 2025.

Because kbd512 has been a proponent of SCO2 systems, the Wikipedia article may provide a way to keep up with developments.

There appear to be advantages to use of SCO2, but it's use must be impeded by disadvantages.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#4 Yesterday 10:37:36

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 23,777

Re: Coal-fired Brayton Cycle Supercritical CO2 Boilers

Here is a list of references Gemini consulted when I asked for an update on SCO2:

ources

ResearchGate

www.researchgate.net

(PDF) Supercritical CO2 Power Technology: Strengths but Challenges - ResearchGate

These difficulties, not anticipated by the precursors of the technology, are linked. to marked specificities of sCO. 2. cycles, in particular their high ...ResearchGate

www.researchgate.net

Comparison of sCO2, CO2 mixture, and steam Rankine cycles for CSP with components sizing: implications for cost and flexibility - ResearchGate

reach higher efficiencies and will have more compact. turbomachinery designs compared to the steam Rankine cycle at. high temperatures [2]. On the other hand, ...MDPI

www.mdpi.com

Supercritical CO2 Power Technology: Strengths but Challenges - MDPI

These difficulties, not anticipated by the precursors of the technology, are linked to marked specificities of sCO2 cycles, in particular their high pressures ...ASME Digital Collection

asmedigitalcollection.asme.org

Performance Analysis of High-Efficiency Supercritical CO2 Power Cycles Using Recompression | J. Energy Resour. Technol. | ASME Digital Collection

The density of supercritical CO2 is roughly double that of steam, and its heat capacity significantly surpasses that of other working fluids [1,2]. These ...Southwest Research Institute

www.swri.org

Technology Today Podcast: The Power of sCO2 | Southwest Research Institute

And the challenge is CO2, because of its properties, means turbo machinery is small. Heat exchangers are small. And at small scales, all your secondary losses ...Oxford Academic - Oxford University Press

academic.oup.com

Innovative power generation systems using supercritical CO2 cycles - Oxford Academic

Introducing a recuperator in the cycle improves the cycle efficiency because a portion of the sensible heat in the turbine exhaust is recuperated and used to ...Southwest Research Institute

www.swri.org

Technology Today Podcast: The Power of sCO2 | Southwest Research Institute

But also, the power cycle - so the turbine, the compressor, all the piping, the control valves, the heat exchangers - are put in the building. Right now, many ...Oxford Academic - Oxford University Press

academic.oup.com

Innovative power generation systems using supercritical CO2 cycles - Oxford Academic

CO2 has a relatively low critical pressure of 7.4 MPa and critical temperature of 31°C. Consequently, CO2 can be compressed directly to supercritical pressures ...

Next is the report by Gemini about the status of SCO2 ... I asked for "headwinds" and it came up with several...

Conversation with Gemini

Supercritical CO2 mechanical applications - Hello Again! Thank you for your help with many previous requests. This one is inspired by a person who is a strong proponent of SCO2 systems for mechanical applications, such as converting thermal energy to mechanical motion. I presume there must be practical reasons why this technology has not yet achieved much traction in industry. Wikipedia has an article about supercritical CO2 that appears to be kept reasonably up to date. What can you find about headwinds that might be slowing adoption of SCO2 as a mechanical energy transformation system?

***

While the mechanical advantages of supercritical CO 2 (sCO 2 )—such as high power density and compact machinery—are well-documented, the technology has faced several significant "headwinds" that have kept it in the development phase for decades.The primary barriers to industrial adoption can be categorized into technical, economic, and logistical challenges:

1. High-Pressure Material and Design Requirements

Unlike steam cycles that operate at relatively low pressures in many stages, sCO 2 cycles require extremely high pressures (often exceeding 200–300 bar) throughout the entire loop.Sealing and Leakage: At such high pressures, preventing CO 2 leaks is notoriously difficult. Standard industrial seals often fail, and CO 2 can diffuse through or degrade many common elastomeric materials.

Material Fatigue: The combination of high pressure and high temperature (over 500–700°C) creates a harsh environment for turbine blades and heat exchangers. This requires expensive nickel-based superalloys or specialized coatings, driving up costs.

2. The "Catch-22" of Turbomachinery Scale

One of the most cited advantages of sCO 2 —its extreme power density—is also a mechanical hurdle.Tiny Tolerances: Because sCO 2 is roughly twice as dense as steam, the turbines and compressors are often 1/10th the size of their steam equivalents. At small scales, the relative impact of "secondary losses" (like tip leakage and friction) becomes much more significant, which can eat away at the theoretical efficiency gains.

+1High Rotational Speeds: To extract work from such a dense fluid in a small package, these machines must spin at very high RPMs (often 20,000 to 50,000+). This creates immense stresses on bearings and requires advanced power electronics or gearboxes to convert that motion into usable 60Hz/50Hz electricity.

3. Complexity of Heat Recuperation

Theoretical sCO 2 efficiency relies heavily on recuperation—reusing the heat from the turbine exhaust to pre-warm the fluid before it hits the main heat source.Heat Exchanger Cost: The heat exchangers needed for sCO 2 must be incredibly "compact" and efficient to handle the massive heat duties. These are often "printed" or diffusion-bonded microchannel heat exchangers, which are far more expensive and difficult to manufacture than the standard shell-and-tube designs used in steam plants.

Inertia vs. Flexibility: While sCO 2 units are physically small, they have high "thermal inertia" relative to their size. Managing the transient states (starting up and shutting down) without causing thermal shock to the high-pressure components is a major control challenge.

4. Economic "Incumbency" and Supply Chain

Steam’s 100-Year Head Start: The steam Rankine cycle is a mature technology with a global supply chain, standardized parts, and a century of operational data. sCO 2 currently lacks a specialized supply chain; many components for pilot plants are "first-of-their-kind" and must be custom-made at a high cost.

Marginal Gains for High Risk: In many applications, sCO 2 offers a 3–5% efficiency bump over the best modern steam cycles. For many utilities and industrial operators, that efficiency gain does not yet justify the "technology risk" of being the first to adopt a system with no long-term reliability track record.

5. Sensitivity to Ambient Conditions sCO 2 cycles are highly sensitive to the temperature of the "heat sink" (the cooling water or air).

The Critical Point: CO 2 becomes supercritical at 31°C. If the ambient cooling temperature is too high (e.g., in a hot desert or during a summer heatwave), the cycle can no longer reach the density needed for efficient compression. This makes the system's performance much more variable based on geography and weather compared to steam.

Current Status

The "traction" is finally starting to pick up. Projects like the STEP (Supercritical Transformational Electric Power) 10MW pilot in Texas and the Allam Cycle (which uses sCO 2 for carbon capture) are currently in the commissioning and testing phases. These projects are intended to prove the long-term reliability that industry currently finds lacking.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#5 Yesterday 10:50:40

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 23,777

Re: Coal-fired Brayton Cycle Supercritical CO2 Boilers

After posting the above, and noting that steam has a major advantage on Earth due to the installed base and the almost negligible advantages of an SCO2 equivalent system, it seems to me unlikely SCO2 will make much progress on Earth.

However, perhaps it is a perfect candidate for power transformation applications on Mars.

In contrast with Earth, water will be ** very ** expense.

In contrast with Earth, CO2 is cheap and available in quantity from the atmosphere.

Perhaps individuals and companies thinking about taking a competitive position on Mars will find SCO2 more than a little interesting.

I'd be interested in seeing how a CO/O2 energy storage system might blend with an SCO2 power transformation system.

I ** may ** have been kbd512 who recommended electric motors for construction equipment on Mars, and stored energy systems other than batteries to provide the electricity.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#6 Yesterday 12:15:28

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 8,413

Re: Coal-fired Brayton Cycle Supercritical CO2 Boilers

tahanson43206,

After posting the above, and noting that steam has a major advantage on Earth due to the installed base and the almost negligible advantages of an SCO2 equivalent system, it seems to me unlikely SCO2 will make much progress on Earth.

Gas turbines and heat recuperators that are 10X smaller than steam equivalents are not an "almost negligible advantage". All that metal and machining costs real money. Even if the steel grades used in a steam turbine are modestly cheaper, they're not 10X cheaper than the steels used in SCO2 turbines. The difference in sizing of the major pieces of plant equipment are "the entire city block" vs "one house on the block". All the stuff in one house can be crammed into a Starship and shipped to Mars. Shipping an entire city block's worth of equipment is not practical. There is no reality-based scenario where any kind of steam turbine comes close to out-performing the SCO2 turbine. It's not cheaper, it's not smaller, it's not easier to repair, it's not easier to assemble and disassemble for transport, it's not faster to ramp-up and ramp-down to load-follow, and it's definitely not minimizing CO2 emissions.

China National Nuclear Corporation already has their first grid-connected SCO2 power plant in Guizhou. It's very small, only a pair of 15MW waste heat SCO2 turbo-generators, but that waste heat was otherwise at the wrong temperature for using steam, because it was waste heat from steel making. Would you rather they burn more or less coal?

The first generation of any new technology will take time to establish its footing. I don't judge combustion engines on the relative success or failure of Ford's Model T. That engine and vehicle was a joke compared to any modern turbocharged inline 4 cylinder engine in a mini SUV. Modern I4's produce as much horsepower and torque as a muscle car era V8, at less than half the weight and displacement. Modern family vehicles are only possible because their turbo I4's deliver V8 torque and power at half the size and weight, all day long.

This article does a good job of indicating exactly how the Allam-Fetvedt Cycle works, why it's a significant improvement over what we presently have in the form of steam and conventional gas turbines, and why Net Power is pursuing it, despite cost overruns and delays, which are related to problems with the Air Separator Units, rather than the SCO2 gas turbines and heat exchangers:

This Power Plant Runs on CO2

One of the reasons it's "good far Mars", is that it recaptures and recirculates the exhaust effluent, instead of dumping it in the atmosphere. It's the first power plant to demonstrate it can do that economically, meaning so much of the power isn't consumed trying to recompress the CO2 for storage that it's not worth the cost and energy involved. It's a CO2 recycling system deliberately built into the power plant as an integral design feature, rather than as an afterthought. Those Air Separator Units will also become critical life support infrastructure pieces for a Mars colony.

Offline

Like button can go here

#7 Yesterday 12:25:55

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 8,413

Re: Coal-fired Brayton Cycle Supercritical CO2 Boilers

A short YouTube video on the Chinese SCO2 gas turbine power plant used to provide additional electrical power to their steel mill without burning more coal:

CGTN News - World's first commercial sCO2 power generator begins operation in China

Edit:

In case the point isn't clear, that steel mill is also a grid-connected power source.

Last edited by kbd512 (Yesterday 12:27:23)

Offline

Like button can go here

#8 Yesterday 14:16:02

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 8,413

Re: Coal-fired Brayton Cycle Supercritical CO2 Boilers

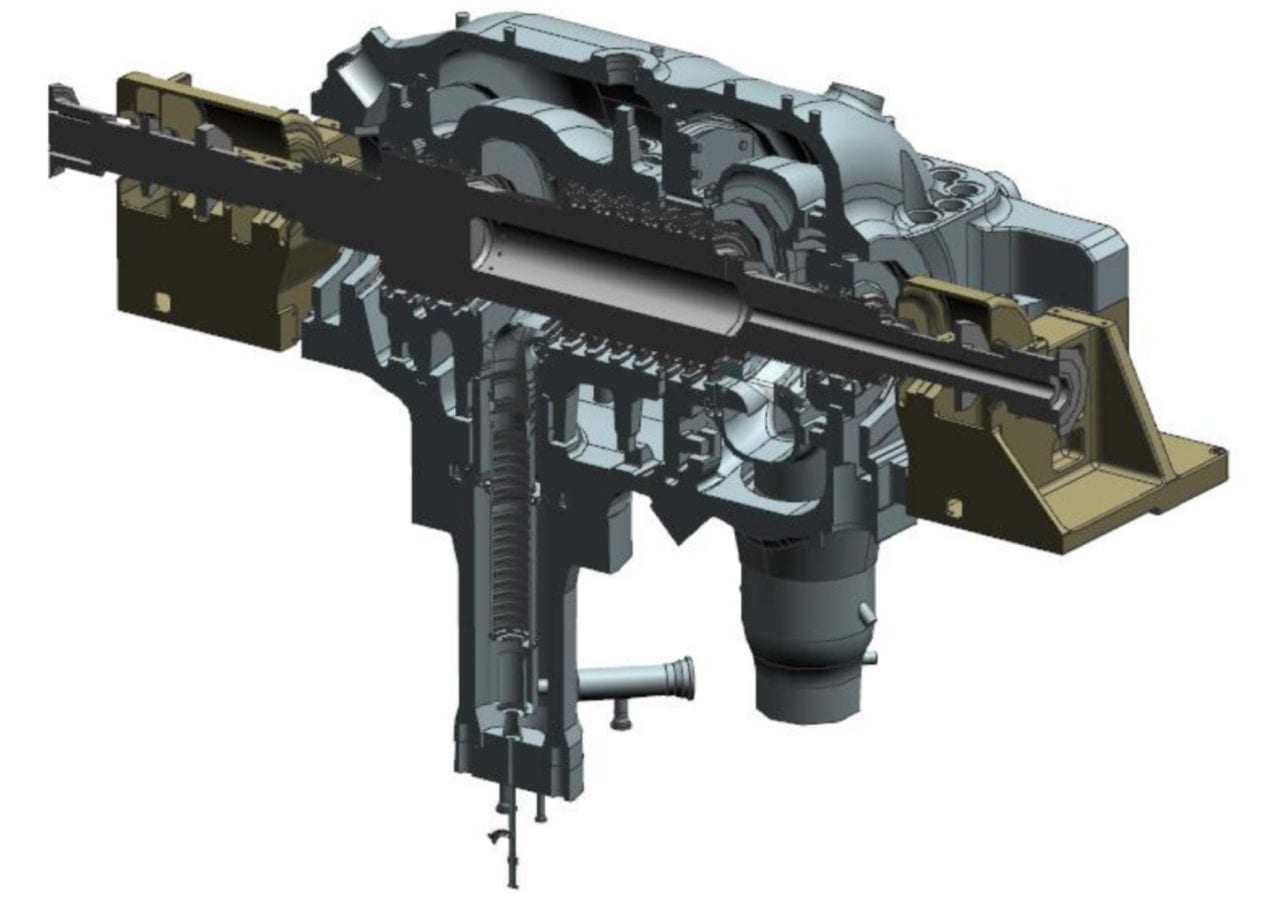

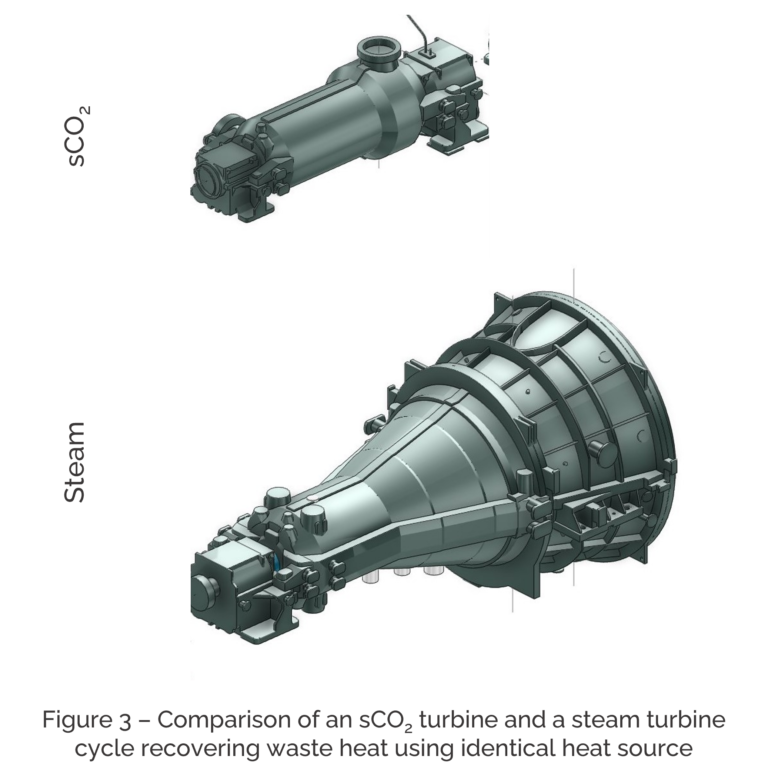

Steam vs Supercritical CO2 Power Turbine Size Comparisons:

The 1GWe SCO2 power turbine will easily fit on a single semi truck. The 1GWe steam turbine? No chance of that ever happening.

Toshiba's 25MWe Allam cycle SCO2 Power Turbine and Combustor Cutaway:

The extra casings surrounding the power turbine are there to recirculate hot CO2.

Edit:

This is a waste heat recovery turbine size comparison between SCO2 and steam:

One of those devices is clearly much smaller than the other.

Steam turbines typically have many many blades that must be very carefully weighed and assembled in a specific order to maintain the balance of the rotating assembly.

SCO2 turbines tend to be machined from monolithic blocks of refractory metal alloys, formed from 3D printed powdered / sintered metal, or precisely cut using wire EDM. This is practical because even 1GW SCO2 power turbines are so small compared to steam turbines.

Last edited by kbd512 (Yesterday 22:31:23)

Offline

Like button can go here

#9 Yesterday 15:22:20

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 23,777

Re: Coal-fired Brayton Cycle Supercritical CO2 Boilers

The Chinese video about the SCO2 plant is well done. It has a polished look. I had the sound off, so can't comment on that.

Down stream from Chinese video I found comments including this one:

@getinthespace7715

8 months ago (edited)

I've been working with supercritical CO2 for about 15 years. It's interesting.

The CO2 NEEDS to be dry. Otherwise, you have to deal with carbonic acid formation and stress corrosion cracking.

Supercritical CO2 is also hard to seal. It will permeate any polymer. Many sealing materials will be destroyed during depressurization. The CO2 inside the sealing material expands more than 50x and explodes out of the seal.

If using the wrong materials an o-ring will sit and crackle like it's full of "pop rocks" after depressurization.

Teflon works ok, but you have to be careful if working at elevated temperatures. Teflon has creep issues and will plasticly deform. The o-rings will shrink when the CO2 permeates out, AND the temperature drops, resulting in a seal that is thinner than when you put it in. Then it no longer contacts both sealing surfaces.

177

It was interesting to see a reference to a 2017 US document on SCO2 included in the Chinese government video.

Recently I heard an assessment of the Chinese people (nothing to do with the government).... the commenter described the Chinese as a "serious people".

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#10 Yesterday 22:25:23

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 8,413

Re: Coal-fired Brayton Cycle Supercritical CO2 Boilers

tahanson43206,

The seals we use are various grades of stainless steels and ceramics, not any kind of plastic. At the temperatures involved it should be obvious why. Virtually every modern piston engine uses multi-layer stainless steel gaskets to hold in combustion pressure. Modern diesel engines use 2,000bar fuel injection pressures and achieve 200bar combustion pressures. The labyrinth seals do leak some CO2, but we also use other inert gases like Argon to put external pressure on the sealing surfaces to hold the CO2 in. Argon is a very heavy gas, so leakage through sealing surfaces is less of an issue. Small Argon filled chambers at each end of the shaft do a good job. A longer shaft also reduces the temperature gradient so there's fewer leaks associated with thermal expansion. The other sealing mechanism we use with longer shafts and lower shaft temperatures is lube oil. Steam turbines already use lube oil.

Stress corrosion cracking can be greatly limited by applying ceramic coatings to the surfaces of the parts. The tech I'm talking about is no different at all than current gas turbine engine tech. Steam turbine and conventional gas turbine blades are also very susceptible to stress corrosion cracking. I've mentioned Silicon Nitride coatings multiple times on this forum, because it's used to coat steam and gas turbine blades, amongst other things.

Offline

Like button can go here

#11 Today 08:08:55

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 23,777

Re: Coal-fired Brayton Cycle Supercritical CO2 Boilers

For kbd512 ... In recent posts, this topic has gained information about:

1) Seals for SCO2 devices

2) Coatings for parts of SCO2 devices

3) (most importantly from my perspective) SCO2 devices may be manufactured by 3D printing

I have a question for kbd512, and will post it shortly...

For any reader who has read this far into a topic about "Coal-fired Brayton Cycle Supercritical CO2 Boilers" it may seem likely that SCO2 has potential for use on Mars. However, it is a very advanced technology. An organization the size of a Nation may be required to make it work on a large scale. We have at least one example reported in the topic, of a large scale implementation in China. However, that report came from a government news source. It would be good to see independent reports that confirm the claims made by the government of China.

This topic could contain detailed information about how to make parts for SCO2 systems using 3D printing.

Potentially, an individual could create plastic models of SCO2 components, printed at large scale for study.

Potentially, large organizations with appropriate resources could create 3D printed parts using the appropriate metals or other materials to make to-scale versions of those parts.

It seems unlikely that specialized coatings can be applied to 3D printed parts using 3D printer technology at it exists in 2025. Thus, this topic could include details about how parts can be given needed coatings.

In short, this topic ** could ** evolve to provide everything an organization would need to build a complete SCO2 power plant on Mars, using only locally procured materials.

So! for kbd512: Can you find examples of 3D printable parts for SCO2 devices? These may be held closely by developers. They would be worth holding close due to their potential economic value. However, not all intellectual property like that is held close, so there may be Open Source versions of such plans. Any part that can be printed at the sizes of SCO2 devices (as you've described them) can also be printed in plastic at much larger scale. Such plastic renditions would be (or could be) valuable as learning devices or teaching devices.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#12 Today 09:43:41

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 23,777

Re: Coal-fired Brayton Cycle Supercritical CO2 Boilers

For kbd512 re quote from Post #1 of this topic...

As the linked design study seems to suggest, the thermal power density for coal-fired Brayton Cycle sCO2 could exceed 1,000MW/m^3. That's a pretty dramatic power density increase over existing steam boilers. The study was published in 2018, and makes the case that going to 700°C temperatures is not economic because it requires Nickel-based superalloys. However, more recent advances in materials, machining, and fabrication methods have already demonstrated cost-competitive superalloy solutions that outperform steam turbines on cost in SCO2 applications, due to the dramatic mass and volume reductions of the machinery involved. We've already begun fabricating SCO2 gas turbine components for SCO2 commercial electric power plants here in Texas, from those superalloys, and the most significant costs seem to be in finding qualified machine shops and welders with the expertise to machine or fabricate the components.

In a very recent post there seemed to be a hint that components for SCO2 devices might be made by 3D printing.

It would be interesting to see how the search for machine shops might match up with the search for qualified 3D Printer organizations.

The skill that humans possess in machining can be transferred to machines. 3D Printers are just one example.

My sense of this situation is that 3D printers might be more productive for a given level of investment, but only Real Universe experience can show which approach is more rewarding for investors.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#13 Today 14:11:19

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 8,413

Re: Coal-fired Brayton Cycle Supercritical CO2 Boilers

tahanson43206,

An organization the size of a Nation may be required to make it work on a large scale.

The portion of the design work that requires truly advanced engineering capabilities is modeling of the turbine's dynamic behavior during ramp-up / ramp-down. You need a supercomputer to do this. Trial and error won't cut it. The reason SCO2 gas turbines didn't exist until about 25 years ago was this exact problem.

It seems unlikely that specialized coatings can be applied to 3D printed parts using 3D printer technology at it exists in 2025.

Chemical Vapor Deposition works on pretty much any part you can throw in the tank.

Can you find examples of 3D printable parts for SCO2 devices?

Easily. Google "3D printed SCO2 turbine components".

SwRI study examines oxide growth in additively manufactured metals in sCO2 environment

Nobody is trying to hide the progress being made on this tech, it's simply not widely reported on. America, China, the United Kingdom, South Korea, Japan, and various other Asian and European Union countries are all working on this technology. It's an area of active development.

The most significant technical challenges are:

1. Modeling turbine flow behavior with SCO2- you really need a supercomputer to do this, and AI would probably help some more

2. Using the correct refractory materials with well-matched CTEs (this actually took quite a bit of experimentation)

3. Modeling and fabricating the heat recuperators and air separator units (for power cycles that use enriched O2)- advanced machining such as chemical etching, diffusion bonding, and selective laser metal sintering are used here, because these units are not like "tube and fin" models used by steam turbines or other more common heat exchangers

4. Long term failure mode analysis with significant thermal gradients and CO2 impurities at-play

5. Selection of appropriate sealing and lubrication materials. This is challenging, but not impossible.

Offline

Like button can go here

#14 Today 17:50:52

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,109

Re: Coal-fired Brayton Cycle Supercritical CO2 Boilers

https://www.grc.nasa.gov/www/k-12/airplane/brayton.html

talked about in several other topic in science folder for thermal energy.

Offline

Like button can go here