New Mars Forums

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

Announcement

#326 2023-10-10 06:21:41

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 23,409

Re: Internal combustion engines for Mars

For kbd512 re #325

SearchTerm:CO O2 engine on Mars compared to electric battery for all terrain vehicle

This post introduces (or re-introduces) the idea of a small turbine engine as an alternative to piston engines which were in mind when this topic started.

The post includes specifics of chemistry, molecular values, mass values and relative cost/complexity/maintainability

***

For kbd512 re further development of the vehicle design with respect to energy investment...

Your post #325 envisions liquid CO and liquid O2 for the vehicle.

It takes energy to compress and cool gas until it is liquefied.

Is there any way to add the cost of the energy needed to liquefy the CO and O2 to the specifications for the CO vehicle vs a battery powered one?

The battery powered vehicle needs the energy to refill the batteries, plus a bit more due to whatever losses there may be.

Let's assume both designs draw power from solar arrays of the same size. The performance difference will show up as time needed to refuel.

For the CO vehicle, the energy investment would include:

1) Capture, filter and compress CO2 from the atmosphere

2) Separate CO from O2 and save the output as gas

3) Liquefy both gases

Given your post figure of 8 hours for operation of the two vehicles, I'm wondering if it is possible to show three values that might be of interest to designers:

1) Energy to load up the battery pack

2) Energy to load up a CO/O2 vehicle designed to use compressed gas instead of liquefied gas

3) Energy to liquefy the gases in #2 - This energy would be added to #2 to give total for the liquefied version

I don't know the answer to how this comparison would turn out, but it sure would be interesting!

The trade off for the vehicle is tank size ... the tank size for the liquid gases would be smaller, and the tanks don't need to be as strong.

The tanks for the compressed gas version would be larger and stronger. I'm thinking of the tanks for compressed air vehicles that a member showed us recently. The post included an image of a tank wrapping machine showing a wide ribbon of plastic material being wrapped by a wrapping machine to achieve an impressive capability with low weight.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#327 2023-10-10 13:19:24

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 8,349

Re: Internal combustion engines for Mars

Topsoe eCOs CO2 to CO Electro-Catalytic Converter

6-8kWh/Nm^3 of CO, so 1.229kg of CO.

1. That means 1,728kWh for manufacturing 354kg of CO and 202.2kg of O2 per day. Direct liquefaction of CO and O2 will be somewhere around 1.5kWh to 1.7kWh/kg with a 8% efficient cryocooler (source is Linde- people who mass manufacture liquid cryogens here on Earth).

2. 601.8kWh daily power use for the CO liquefaction.

3. 343.74kWh daily power use for the O2 liquefaction.

4. 2,673.54kWh or 2.673.54MWh of total daily power draw for the CO and O2.

5. I don't know how much power is required to obtain liquid CO2 feedstock, because if it's done at night then it requires very little power.

6. 596.56kWh total daily power consumption for the battery, or about 4.48X better.

There's a problem with this simpleton calculation, though. The battery cannot recharge from a solar panel at night, unless a second full-sized battery is also present. There's another problem related to battery longevity. If you discharge 100% of the battery capacity from Lithium-ion, cycle life is about 1,000 to 2,000 cycles, so 2,000 driving days tops, so 5.5 years before replacement. In reality, it's 11 years before replacement because this silliness doesn't work without 2 complete 596.56kWh batteries, one on the charger, the other in the vehicle.

Assume you get an average of 238.175W/m^2 of solar panel surface area (35% efficient, twice as far from the Sun as Earth), and 1,429Wh/m^2/day. This is realistically achievable under optimal conditions near the equator.

sCO2:

2,673,540Wh / 1,429Wh = 1,871m^2 of solar panel area

(3,742kg at 2kg/m^2 using Triple-Junction monocrystallane wafers on a honeycomb CFRP backer board, which I proposed before, to try to get the mass of Louis' all-solar setup down to something manageable, and then it still couldn't compete with nuclear)

Li-ion:

596,560Wh / 1,429Wh = 418m^2 of solar panel area (836kg)

5,965.6kg for pair of 596.56kWh batteries + 836kg of PV = 6,801.6kg for Li-ion and PV

350kg for sCO2 turbine setup in vehicle + 3,742kg of PV = 4,092kg for sCO2 and PV

I can afford to add extra cryogen tanks, weight for the electrolyzer equipment, insulation, power cables, etc. Regardless, I'm coming in under the mass and volume of an equivalent battery powered system.

Assume the weight of the power control electronics for sCO2 PV is 4.5X heavier than Li-ion (can't easily estimate weight for this- AC vs DC, voltage and amperage, etc, all greatly affect the numbers for both solutions). No weight is added to the battery vehicle for power control electronics, or electric motors, or radiators, nor the structural support hardware for a much heavier battery- even on Mars this still matters. That is how low the energy density of Lithium-ion batteries is, when compared to a system that must produce oxidizer and fuel from scratch. A vacuum-rated battery pack is nowhere near 200Wh/kg at the pack level, either, more like 100Wh/kg.

We'll use every trick in the book to reduce the weight of the battery vehicle and increase the power efficiency of the sCO2 vehicle, but at the end of the day energy density differences between a fuel 4X worse than Methane vs a Li-ion battery show how far behind batteries are compared to any type of combustion engine.

We're talking about liquid cryogen vs batteries, not compressed gases, but it wouldn't matter if we were using compressed gas, and I've shown this before with Meth-Ox. You cannot overcome a 5X to 10X energy density deficit of CO / O2 vs Li-ion. It's not possible. I know our battery and solar panel advocates want it to be possible, but simple math shows that it's not. Batteries are best reserved for laptops, cell phones, flashlights, radios, light duty indoor-use power tools, and starting real engines. They are not acceptable substitutes for combustion engines, even when you synthesize the fuel from scratch, even when you have to store the fuel and oxidizer, even when the fuel and oxidizer are not even 1/4 as energy dense as Methane.

If weight matters, and on Mars it matters quite a lot, then you get drastically more "bang for your buck" using combustion engines. That's why Mars Direct featured a CH4 / O2 combustion engine rover. Dr Zubrin is an aerospace engineer who is unencumbered by ideology. He does things that make sense from a energy / mass / volume / cost perspective.

Offline

Like button can go here

#328 2023-10-10 14:41:58

- Calliban

- Member

- From: Northern England, UK

- Registered: 2019-08-18

- Posts: 4,269

Re: Internal combustion engines for Mars

Kbd512, a good analysis. I have often wondered if it would make sense landing fuel factories on Mars, along the routes that a rover would take to reach scientifically interesting sites. These would be small units, probably no more than a few hundred kg each. We could ship a thousand of them to low Mars orbit in a single starship payload and then land them where we expect to use them. They would each be equipped with solar panels or a kilopower unit and would convert Martian CO2 into cryogenic CO and O2. The rover would drive between fuel stations, which could be spaced a couple of hundred miles apart.

Regarding the solar electric solution for vehicles. How would the analysis stack up for a direct solar electric powered vehicle, without batteries? This would involve directly powering a DC motor using solar panel. Speed would be a function of sunlight intensity, so there would be no driving at night and probably no driving outside of an 8 hour window every 24 hours. The power available to the vehicle would be limited by the surface area of panels that could be mounted on the vehicle. So I would imagine this would be slow, probably no more than human walking speed. A bit like being stuck in first gear. But a vehicle like this would not need to carry propellant. Dust storms could be the thing that screws it up.

"Plan and prepare for every possibility, and you will never act. It is nobler to have courage as we stumble into half the things we fear than to analyse every possible obstacle and begin nothing. Great things are achieved by embracing great dangers."

Offline

Like button can go here

#329 2023-10-10 17:32:50

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 8,349

Re: Internal combustion engines for Mars

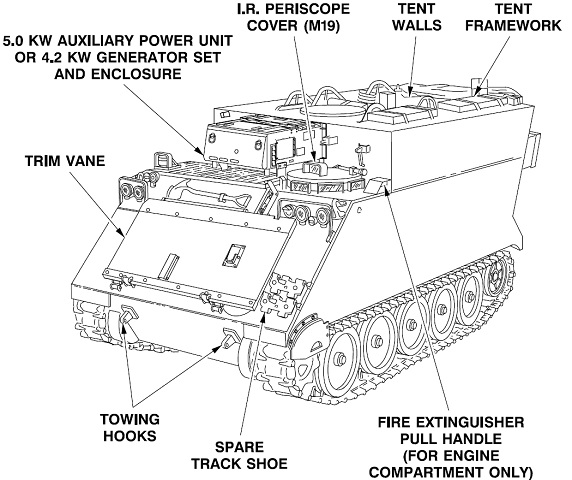

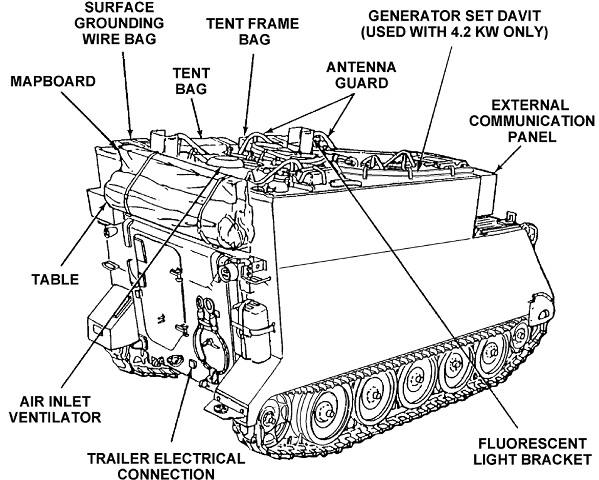

M1068 Standard Integrated Command Post System Carrier (M113 APC Variant)

Length: 4.85m

Width: 2.7m

Height: 2.7m

Ground Clearance 435mm

Combat Weight: 12,172kg (Earth); 4,625kg (Mars)

Horsepower Required: 275hp (Earth); 104.5hp (Mars- this is where the 100hp / 74.57kW figure comes from)

Ground Pressure: 8.68psi (Earth); 3.2984psi (Mars- it "floats" across sand that a human foot would sink into)

Engine:

Detroit Diesel 6V53T

Dry Weight - 769kg

Displacement - 5.2L

Power - 212hp gross at 2,800rpm

Torque - 492ft-lb at 1,300rpm

Engine Dimensions - 991mmL x 940mmW x 1041mmH

Max Level Road Speed: 40mph (Earth); 25mph (Mars; 100% off-road)

A fold-out 400m^2 solar array on its roof, using a tilt / swivel truss structure, could nominally provide 95,270Wh per hour, during a 6 hour timeframe, when the sun shines the brightest (10AM or 11AM to 4PM or 5PM). The rest of the power is for life support, keeping batteries and tracks warm, sensors, radios, airlock, etc.

What effect would 800kg at least 5m above the ground, not including wiring and support structure have on this vehicle's stability?

I dunno, but you never want to climb or descend a hill at a perpendicular angle. I can tell you that much. If thin film with a scratch-resistant "Gorilla Glass" covering was much lighter than 2kg/m^2, then perhaps that would reduce stability concerns.

For sCO2 power, a solar thermal reflector can supply 612.45Wt/m^2 (because we're not attempting a 35% efficient conversion). Let's say we get 306.225W of thermal power (50% efficiency). That reduces solar array size to 243.5m^2 (15.6m x 15.6m), which is somewhat less unwieldy, but then the material has to keep the semi-flexible solar concentrator focused on the hot spot while the vehicle is bouncing around.

Offline

Like button can go here

#330 2023-10-12 01:15:47

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 8,349

Re: Internal combustion engines for Mars

A Strontium-90 power source providing direct heat to a sCO2 gas turbine, would probably weigh about half as much as the battery. It would require a larger radiator than the CO / O2 option, but it's still less of a hassle than CO / O2 synthesis or recharging batteries with photovoltaics, and it's made from a nuclear waste product.

Strontium-90 Titanate (SrTiO3)

Melting Point: 2,080C

Density: 5.11g/cm^3

Heat Production: 450W/kg

Surface Temperature: 700C to 800C

149,140W / 450W/kg = 331.42kg (at 50% efficiency, this is how much SrTiO3 you need)

331,422.22g / 5.11g/cm^3 = 64,858cm^3 / 64.858L (40.2cm by 40.2cm by 40.2cm)

At 715C, the prototype 2-stage 250kW sCO2 gas turbines achieved 50% thermal-to-mechanical efficiency. A 250kW sCO2 gas turbine wheel is about the same diameter as the US Quarter Dollar coin. If we want minimum weight, minimum hassle, and guaranteed thermal performance, then this is the way to do it. We could have 4 RTGs for redundancy, with each one providing 1/4 of the total thermal power input, 4 sCO2 turbines for redundancy in case one fails, each capable of full output, with associated valves and piping to cut out a failed turbine or coolant loop, plus smaller fully redundant gas turbines to supply electrical power to the life support equipment.

This won't be a solution for all types of vehicles, but for long-range surface exploration / transport vehicle can use Strontium to avoid the need to lug a bunch of extra equipment with the vehicle. Short range ATVs for quick transits between pressurized base structures can use compressed CO2 and Sr90 heat sources. Base construction equipment can use direct solar with power cables and batteries, with backup sCO2 gas turbine generators or fuel cells. I think these solutions use the best mix of technology capabilities where they're most appropriate.

The whole air transport thing that GW alluded to elsewhere? Well... I don't think we're going to do much flying. As GW pointed out, it's very dangerous to fly so fast so close to the surface. If a reliable nuclear decay heat powered land transport is available, then it obviates the need for high-speed air transport between colonies. If ace pilots want to try their luck providing air transport of medical supplies or transfer of injured personnel back to the main base, then we can test the practicality of rocket-powered hoppers or propeller-driven aerodynamic lift / rocket VTOL aircraft. I don't think helicopters are practical at the scale required.

Vstall: 115kts

Vcruise: 150kts

Max Gross: 6,000lbs

Wing Area: 2,080ft^2

Wing Loading: 2.885lbs/ft^2

Dr Raymer is postulating 500Wh/kg batteries by 2030, which don't presently exist, so I'm substituting H2 fuel cells. ZeroAvia reports that their test stacks achieve 2.5kW/kg in their 20kW test stacks. Hydrogen provides 33.33kW/kg, we're going to assume 65% efficency, so 21.67kWh/kg of H2. His notional 834lb 500Wh/kg (417kWh) battery is being replaced by 19.25kg of LH2 and 154kg of LH2, or 382lbs of reactants for the fuel cell. If we include the weight of the fuel cell, we're at 470lbs. Batteries need to achieve 1,000kWh/kg before we have lighter batteries. If the cryogen tanks are 5% the cryogen mass, then we're at 489lbs total. He's showing cruise power of only 31.2hp / 23,266W. I'm not sure if that's correct or not, because it seems quite low, but I'll run with his numbers since I'm not a PhD aerospace engineer.

Scratch that! We already have single-use Aluminum-air batteries that achieve 1,200Wh/kg. It then takes 12kWh to 15kWh of electricity to convert the Alumina, back into Aluminum, but Aluminum-air batteries already exist and have existed at that power density level for years now. They're not practical for Earth-bound cars, but a Mars airplane can justify the 15X energy input premium. Jackpot. Batteries are finally helping us out by doing a better job than competing alternatives. Go wild, battery advocates. We finally found an application where batteries are superior to competing alternatives. We do need to carry a more modest supply of O2 with us, because oxidation of the Aluminum makes the electricity.

I don't like the crazy amount of wingtip flex in his 345ft wingspan aircraft, so I'm specifying a box wing / biplane configuration. As Dr Raymer indicated, it will have a significantly greater amount of drag, but a box wing is not as unwieldy, fragile, and heavy. The 2,000km of range is great, but flying such a small aircraft for 6 hours is impractical. 4 hours of flying is more practical. Even if the box wing reduces the range to 1,000km, a more practical aircraft is still worth the tradeoff. It's still a 141ft wingspan, which is a little nuts for a 2-seater. A 345ft wingspan is grossly impractical, though. A C-130's wingspan is only 132ft.

Offline

Like button can go here

#331 2023-10-12 16:01:13

- Calliban

- Member

- From: Northern England, UK

- Registered: 2019-08-18

- Posts: 4,269

Re: Internal combustion engines for Mars

The problem with Sr-90 as an RTG heat source is bremsstrahlung emissions. The strontium nucleus has a high charge density, and any beta electrons approaching it are deflected at wide angles, causing them to emit x-rays. This is why beta shielding is usually light elements like carbon and hydrogen. In terms of abundance, Sr-90 would be a far more practical RTG isotope than 238Pu. But those pesky x-rays make it difficult to handle. Pure Sr-90 has power density of 0.95W/g. So a tonne of Sr-90 will give you 1MWth. Strontium titanate achieves about half of that. One option would be Sr-Li liquid alloy.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF02877514

This has the added advantage of being liquid, allowing convective heat transfer. Sr-90 is some 15x more massive than Li-6, so even a high molar proportion of lithium will only weakly dilute the mass power density. A high molar concentration of Li ensures that most of the beta deceleration is accomplished by a light element, reducing bremsstrahlung emissions. This allows the GT to avoud the need for shielding. A gas turbine engine on Mars could consist of Sr-Li within steel or nickel tubes, which would be in a tapered chamber directly behind the compressor. The heated CO2 would then pass through the turbine, a portion of whose work would drive the compressor through an axial shaft.

Because we are relying upon heat transfer from solid tubes into a gas stream, a high compression ratio is highly desirable, as heat transfer is proportional to gas density. The low temperature of the Martian atmosphere, which is far beneath critical point of CO2, makes this achieable without the compressor eating up all of the turbine work. For this reason, a nuclear or RTG gas turbine may work much better on Mars than on Earth. Although the Martian atmosphere is thinner, the cold CO2 does not behave like an ideal gas. Compared to air, far less work will be required to achieve a volume change.

Last edited by Calliban (2023-10-12 16:12:12)

"Plan and prepare for every possibility, and you will never act. It is nobler to have courage as we stumble into half the things we fear than to analyse every possible obstacle and begin nothing. Great things are achieved by embracing great dangers."

Offline

Like button can go here

#332 2023-10-12 18:48:24

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 29,886

Re: Internal combustion engines for Mars

If we are going to use heat energy from a burn chamberwhen using turbines coupled with electric generation from the motion that is created does yield a bit more than the typical 25% but we can also do more with the chambers heat by wrapping it with vapor coils to obsorb the heat to make more energy and then the exhauist heat can also be captured for the same purpose. That said we can alter the current KRUSTY design to perform this function of power from heat.

Offline

Like button can go here

#333 2023-10-12 23:32:12

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 8,349

Re: Internal combustion engines for Mars

Calliban,

I never thought about the possibility of using a light molten alloy, but better power density and reduced core volume and weight is very attractive. I still don't think you can get away with no X-ray shielding. Maybe it can be reduced by quite a bit, though. The Sr90 is still going to interact with the walls of the storage container, producing X-rays. My initial thought process was that the exterior would be properly shielded and we'd have SrTiO3 plates with holes for the CO2 to flow through, much like NERVA's core. Regardless, the volume claim inside the vehicle is much lower compared to competing solutions.

What are your thoughts on using Indium-Tin-Bismuth for thermal power transfer?

The vehicle could have a tank of molten metal surrounding the RTG, to draw excess power from, in case the vehicle needs a burst of energy for climbing hills, operating hydraulic dozer blades or grading blades or power shovel attachments, providing thermal power transfer to the base's backup thermal power storage when not being driven, a heat source for compressed CO2 power tools, etc?

We're losing thermal power whenever the vehicle is not being driven, so we may as well have a method to transfer surplus power for other applications.

Offline

Like button can go here

#334 2023-11-15 18:20:38

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 29,886

Re: Internal combustion engines for Mars

What I found was poor Isp performance with LOX-LCO, due to low c*. But if it is readily available, you may not care about that. It won't get you into orbit or halfway around the planet as a rocket propellant, but it might serve for short-range "local" stuff.

I suspect that in some sort of internal combustion engine, it would perform about like methanol. Just remember, that on Mars, you have to carry the oxygen (which outweighs the fuel), and a diluent gas (which outweighs the oxygen), to operate internal combustion devices as we know them here.

If you are willing to undertake the extensive redesign to handle 500-1000 C higher flame temperatures, you can delete the diluent gas. All fuels burn with air at about the same temperatures at the stoichiometric mixtures, whether low or high energy.

GW

Offline

Like button can go here

#335 2023-11-16 00:30:10

- Calliban

- Member

- From: Northern England, UK

- Registered: 2019-08-18

- Posts: 4,269

Re: Internal combustion engines for Mars

Some gas turbines have combustion chamber temperatures exceeding 1500°C. The blades are single nickel alloy crystals with cooling tubes actually cast into them. Very impressive. Unfortunately, adiabatic flame temperature of most fuels approach 3000°C in pure O2. There aren't many metals that can withstand those temperatures for very long without severe erosion.

https://www.thoughtco.com/flame-tempera … ble-607307

Maybe instead of using CO2 or N2 as diluent gas, we could use water? If water can be recondensed from the exhaust, we can reuse it and reduce the mass that must be carried. The problem here is that a large radiator is needed to cool the exhaust gases to the condensation point of water. Carbon dioxide is a more obvious choice for diluent gas on Mars, because the vehicle can refill an LCO2 tank from the air when it is parked. The waste CO2 can be vented back into the air without cooling, carrying waste heat with it.

Last edited by Calliban (2023-11-16 00:38:54)

"Plan and prepare for every possibility, and you will never act. It is nobler to have courage as we stumble into half the things we fear than to analyse every possible obstacle and begin nothing. Great things are achieved by embracing great dangers."

Offline

Like button can go here

#336 2023-11-17 11:19:21

- GW Johnson

- Member

- From: McGregor, Texas USA

- Registered: 2011-12-04

- Posts: 6,101

- Website

Re: Internal combustion engines for Mars

The gas temperature in a turbine's combustor cans is not uniform. There is a hot spot in the core where the mixture is just right, that can approach 4000 F, but things are cooler all around it. Right at the forward dome, it is too rich to ignite, being nearly all fuel. Air is added from the sides as you proceed down the can, and amounts to temperature-lowering dilution air in the downstream portion of the can. Mixed gas temperature must be down to the allowable turbine inlet temperature range by the time it leaves the can, which is under 2200 F, and under 2000 F in older designs.

The combustor can is a double-wall device: a pressure vessel containing air from the compressor, with a perforated liner. The fuel is sprayed inside the perforated liner, at its forward end, and (usually) combustion within that perforated liner is spark ignited just downstream from there, where the mixture is just rich of stoichiometric. The perforated liner is bathed in compressed air on its outer surface, and by combustion gases on its interior surface. That air can only be moderately hot from compression (both inlet ram and compressor stages) before it is effectively no longer the "cooling air" that allows the perforated liner to survive.

That over-temperature risk in the combustor cans, the risk to the turbine blades, the risks to the compressor blades, and the risks to afterburner and nozzle components are why gas turbine engines for flight to Mach 3 are so rare and expensive. There have been only 3 so far that qualify as production engines: in the XB-70 (Mach 3.0), the SR-71 (Mach 3.2), and the Mig-25 (Mach 3.5). The Mig-25 engine had only a 500-hour service life, at the end of which you did not overhaul it, you replaced it with a new one.

GW

Last edited by GW Johnson (2023-11-17 11:22:17)

GW Johnson

McGregor, Texas

"There is nothing as expensive as a dead crew, especially one dead from a bad management decision"

Offline

Like button can go here

#337 2024-01-23 09:42:10

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 29,886

Re: Internal combustion engines for Mars

6 cycle water engine

https://youtu.be/gMe8D_PbJ30?si=4SWEaRnaRHJGFnyJ

Offline

Like button can go here

#338 2024-01-23 10:53:39

- GW Johnson

- Member

- From: McGregor, Texas USA

- Registered: 2011-12-04

- Posts: 6,101

- Website

Re: Internal combustion engines for Mars

That's the first time I've ever seen the 6-stroke cycle for an internal combustion engine. The water gets vaporized by the residual exhaust gases after the exhaust valve closes, and the resulting steam can't get out, so it pushes down on the piston for the second power stroke.

The second exhaust stroke has to clear out the steam so that it does not quench the fuel-air mixture from igniting in the intake and compression strokes. That's a big risk to successful running, by the way.

I don't know that I agree about the need for distilled water, but it will at least have to be potable water. Which is going to get scarcer as the population gets larger and the climate keeps warming. Just something else to worry about.

The water is a second, smaller flow of liquid into the engine, and it has to come from a second tank. This thing still burns a fossil fuel. That is a technology at least conceptually posing the risk of putting the wrong liquids in the tanks.

With the steam pulses out the exhaust valve, I rather doubt that our existing emission control technologies will work right. The steam will be a much higher percentage of the exhaust stream on average, and at discrete points in time, it will dominate. Our catalytic converters may not work right.

Although, the cat converter should stay cleaner of life-shortening soot, due to the cleaning action of the steam. If it doesn't work right, then NOx is a very potent source of greenhouse warming, in addition to being a source of health effects and acid rain. Something else to worry about.

I'm no expert, and I could be wrong about these things. But they need to be worried about, and that's what the "engineering development" of this thing would be all about. That's expensive, time-consuming work. It cannot be both fast and accurate.

BTW, this is not the "water engine" that some crack it up to be. There are other things also claimed to be "water engines". But there is no such thing, that would violate the 2nd Law of Thermodynamics!

Why do I say that? It costs more to split the water into hydrogen and oxygen than you can get back from re-burning them, because NOTHING is 100% efficient.

There are some things that come close to high efficiency, but NONE of them have ever been heat engines of any kind. The upper bound on heat engine efficiency is the Carnot efficiency. It rarely even approaches 30%. Properly evaluated, the high temperature in the Carnot efficiency is your combustion temperature, and the low temperature in it is the exhaust gas temperature, NOT the ambient atmospheric temperature!

Why, when so many use the atmosphere temperature? Because what goes on downstream of the exhaust valve is UTTERLY IRRELEVANT to whatever happens inside the cylinder, as long as the pressure is near atmospheric. And what goes on inside the cylinder is what thermodynamic modeling is all about.

GW

Last edited by GW Johnson (2024-01-23 10:57:57)

GW Johnson

McGregor, Texas

"There is nothing as expensive as a dead crew, especially one dead from a bad management decision"

Offline

Like button can go here

#339 2024-01-23 11:54:55

- Calliban

- Member

- From: Northern England, UK

- Registered: 2019-08-18

- Posts: 4,269

Re: Internal combustion engines for Mars

One wonders why the designers would opt for such a complicated cycle? Why not pass the exhaust gases through a heat exchanger and keep the steam and exhaust gases seperate? For that matter, the primary stage could be a small GT with better P/W than a piston engine. GT powered cars are nothing new. Power can be spectacular, but fuel economy has always been on the low side of mediocre. A two-stage engine combining a GT with steam cycle, with a heat exchanger between the two, would probably beat a piston engine on both P/W and fuel economy. I can't imagine that this idea hasn't occured to the people that design new cars. I would imagine development costs have prevented this innovation.

"Plan and prepare for every possibility, and you will never act. It is nobler to have courage as we stumble into half the things we fear than to analyse every possible obstacle and begin nothing. Great things are achieved by embracing great dangers."

Offline

Like button can go here

#340 2024-01-24 13:49:38

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 8,349

Re: Internal combustion engines for Mars

Is anyone else here familiar with turbo-compounding?

The big radial engines of WWII fame used it to good effect after the war, before jet engines took over airliner service. The Wright R-3350 was a pretty famous example of turbo-compounding, as-used in the Douglas piston engine airliners, as well as the Boeing B-29. As far as engine efficiency is concerned, recovering the energy in the waste heat of the exhaust gas is a great place to start. Ye olde radials connected an output shaft from the turbo to the crankshaft, but that's not the only way to do it. The turbo can spin an electric generator and it can spin-up a flywheel as well, for faster acceleration using a less powerful engine that runs at full rated output at all times for sake of thermodynamic efficiency.

The Pratt & Whitney PT-6A turboprop is an example where the exhaust gas spins a free turbine not connected to a turbine wheel aft of the hot section, so that it doesn't need to "spin" at the exact same speed as the primary shaft that the compressor section is connected to. The Garrett TPE-331 (or whatever they call it now) is an example of a turboprop engine where the compressor and hot section are all connected to the same shaft. General Electric also makes very large geared turbofan engines that prevent the tips of the fan blades (which provides most of the thrust, but is much larger in diameter than the compressor section fan blades, and would thus ordinarily be moving at much higher velocity if everything was directly connected on one shaft), from going supersonic.

Anyway, turbos and gearing allows different parts of an engine to spin at very different speeds so the component in question can perform more optimally, increasing overall combustion efficiency by facilitating airflow through that explosively-driven air pump.

Offline

Like button can go here

#341 2024-01-25 12:55:13

- GW Johnson

- Member

- From: McGregor, Texas USA

- Registered: 2011-12-04

- Posts: 6,101

- Website

Re: Internal combustion engines for Mars

2+ decades ago when I worked at Baylor U in the Aviation Sciences department, the department had a test truck with a PT-6 and a "club" prop mounted on it, to use as a test facility to evaluate alternate turbine fuels. I designed the steel mount for the engine, and the steel outrigger stabilizers that took the loads into the pavement. I also set the mounting angle such that the occupants in the truck bed half-box that was the test cabin, would survive either an engine fire or an uncontained engine core failure.

I used that facility with permission while teaching an aircraft systems course. I brought the students out and had them operate the PT-6 and prop pitch as part of teaching how gas turbine engines worked. The idea was to make the dry classroom content "real" to students training to be future airline pilots, who would otherwise get most of their training flying piston aircraft. My students all told me (and others), that that class was the very best one they had, at Baylor.

Experimentally, I tested biodiesel blends with Jet-A in that PT-6. I would diagnose combustion problems by stepping into the blast and sniffing the odors. I could tell the source of the biodiesel: converted grease from the fast food places smelled like French fries cooking, and converted tallow from the slaughterhouse smelled like barbecue cooking. Any time the burner cans were not fully efficient, you could smell kerosene in the stream.

It turns out that the biodiesel in the blend actually rejuvenates old fuel bladders that are getting stiff. That was a pleasant surprise to me and the FAA. That result was a part of how I was able to put a Beech King Air into "experimental" for flight tests of the experimental fuels, and still bring it back to "standard", all in 6 months. The other part was exposing only one engine, and doing a hot section overhaul on that exposed engine before going back to "standard".

This was all 1998-vintage stuff, long before the current "sustainable" fuels.

GW

Last edited by GW Johnson (2024-01-25 12:58:38)

GW Johnson

McGregor, Texas

"There is nothing as expensive as a dead crew, especially one dead from a bad management decision"

Offline

Like button can go here

#342 Yesterday 14:59:09

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 29,886

Re: Internal combustion engines for Mars

tahanson43206,

If you have to carry the fuel and oxidizer with you, as you would on any planet except Earth, then pure Carbon doesn't require extra Oxygen atoms to combine with the Hydrogen atoms.

Kilograms of Pure Oxygen for Complete Combustion of 1kg of fuel:

Pure Carbon (32.8MJ/kg; 1kg powdered graphite = 1.05-1.15L; 28.52MJ/L): 2.67kg (2.34L); 3.49L ttl vol, 9.40MJ/L incl O2

Gasoline (44-46MJkg; 1kg = 1.2-1.4L; 32.86MJ/L): 2.3-2.7kg (2.37L); 3.77L ttl vol, 12.20MJ/L incl O2

Kerosene (43-46MJ/kg; 1kg = 1.25L; 36.8MJ/L): 2.93kg (2.57L); 3.82L ttl vol, 12.04MJ/L incl O2

Diesel (42-46MJ/kg; 1kg = 1.16-1.2L; 38.33MJ/L): 3.4kg (2.98L); 4.18L ttl vol, 11.00MJ/L incl O2

Methane (50-55.5MJ/kg; 1kg LCH4 = 2.36L; 23.52MJ/L): 4kg (3.51L); 5.87L ttl vol, 9.45MJ/L incl O2

Hydrogen (120-142MJ/kg; 1kg LH2 = 14.1L; 1L = 10.07MJ/L): 8kg (7.01L); 21.11L ttl vol, 6.73MJ/L incl O2LOX is 1,141kg/m^3 or 1.141kg/L

What can we conclude from that?

1. LH2 is a pretty pedestrian fuel when you need to store the cryogenic oxidizer, too.

2. There's not much difference between pure Carbon powder and Methane, except that making Methane is a lot more difficult and requires a lot more energy and technology than bubbling collected CO2 through a column of liquid Gallium eutectic. You need equipment to collect both H2O and CO2, a Sabatier reactor, a reverse fuel cell, and a really good electrical power source.

3. You do get 17% to 30% more energy per total volume by combusting diesel / kerosene / gasoline, in comparison to Carbon powder, but if you thought making Methane was energy intensive, you're going to need to add a lot more energy-intensive equipment to your chemistry set, and of course, you only get that additional energy by combusting it using additional O2 mass, which means you need to make more O2 from some combination of H2O and CO2. It's a pretty safe bet that all those additional chemical reaction steps will cannibalize whatever gains a dense liquid hydrocarbon fuel provides.

4. The relative complexity of obtaining LCO2 feedstock, on Earth or Mars, is pretty low. It's everywhere in the atmosphere and in the oceans here on Earth. Mars helps us out a bit by having a nearly-pure CO2 atmosphere, but at absurdly low density. Speaking of absurdly low density, LH2 looks great, best of all fuels, except when you must consider the mass of the storage equipment, and then it doesn't look so hot.

5. Of all the fuels listed, and any other liquid hydrocarbon fuels that weren't, if you throw a kilogram of Carbon on the ground, here on Earth or on Mars, that same kilogram of pure Carbon fuel will still be there the next day. We can't make the same claim about any of those other fuels. Carbon doesn't require special storage of any kind. If storing a cryogenic oxidizer is a pain we'd rather not deal with, then why compound the problem with fuels which also have special storage requirements?

Which means we have a place to ship Earths coal and a use for the raw ore.

Offline

Like button can go here

#343 Yesterday 16:03:15

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 23,409

Re: Internal combustion engines for Mars

For SpaceNut re post https://newmars.com/forums/viewtopic.ph … 91#p236091

kbd512 seems to have written with a bias toward using solid carbon.

Solid carbon is not a suitable fuel for an internal combustion engine that uses pistons.

Is there something in that post that you think might be helpful for someone trying to design an internal combustion engine that uses pistons on Mars?

How do you think our readers would be able to use the information that kbd512 wrote?

As you probably noted, carbon is available for free on Mars, so there is no reason to ship carbon from elsewhere.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#344 Yesterday 16:16:09

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 29,886

Re: Internal combustion engines for Mars

Yes, coal can be used in engines similar to wood gas systems, using a gasifier to create flammable synthesis gas (syngas) from the solid fuel, which is then filtered and fed to a modified internal combustion engine, though wood/charcoal was more common during WWII

fuel shortages;

both work by heating fuel in low oxygen to produce combustible gases like Carbon Monoxide (\(CO\)) and Hydrogen (\(H_{2}\)) for powering vehicles or generators, with coal offering steadier, hotter burns but requiring more robust filtration for dust.How Gasification Works (Wood & Coal) Gasification Process:

The fuel (wood, charcoal, or coal) is heated to high temperatures (900-1200°C) in a reactor with restricted air, causing partial combustion and thermal decomposition (pyrolysis).Syngas Production:

This process creates a flammable gas mixture, primarily Carbon Monoxide (\(CO\)) and Hydrogen (\(H_{2}\)), known as synthesis gas or "wood gas" (even with coal).Cooling & Filtering:

The hot gas is cooled and filtered to remove tar, water, and ash particles, preventing engine damage.Engine Fuel: The cleaned syngas is then drawn into the engine (like a car or generator) to power it, replacing gasoline. Similarities &Differences Principle:

The fundamental gasification principle is identical for wood and coal, converting solid fuel into a usable gas.Fuel Handling: Coal burns hotter and longer but produces more dust, requiring better filtration than some wood setups.Usage:

Both were used during fuel shortages (like WWII) to run vehicles and generators, with wood gas more prevalent due to fuel rationing. Engine Adaptations Standard internal combustion engines can be modified to run on this gas by adding the gasifier unit, filters, and controls.Systems often include a hopper for fuel, a reactor/burn chamber, filters (cyclone, radiator), and a blower

To make carbon monoxide, carbon must be burned in an atmosphere with limited oxygen. This releases about 20% of the heat released by complete combustion. The process that Kbd512 has described produces particles of carbon. So that is what we start with. Carbon monoxide has important uses of its own. One such use is the production of reduced iron. Making strong engineering bricks is another use we have noted. But it is a precursor to other more convenient fuels. For example:

CO + H2O + heat = CO2 + H2

2H2 + CO = CH3OH.This is methanol. It is a clean burning liquid fuel that doesn't freeze until -97°C. We could store it in tanks on Mars with very little pressurisation.

Offline

Like button can go here

#345 Yesterday 18:51:32

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 23,409

Re: Internal combustion engines for Mars

This conversation with Gemini is about Carbon Monoxide and other fuel combinations.

I thought the discussion of long distance travel vs work machinery was interesting and possibly worth someone's time to study.

Conversation with Gemini

Make Carbon Monoxide from CO2 - Hi Gemini ... this question is about how to make carbon monoxide without replicating the ancient Earth technique of burning coal in a vessel with limited oxygen. I'm sure there must be highly efficient methods to separate one Oxygen atom from CO2 leaving CO behind.

You are asking about CO₂ reduction, a major field of study in modern chemistry, particularly for creating synthetic fuels and in carbon capture utilization.

While the "burning coal" method (incomplete combustion) is indeed ancient, you are correct that modern science has developed sophisticated ways to strip that oxygen atom. However, a crucial reality check is necessary first: CO₂ is an extremely stable molecule. It is the "ash" of burning carbon; it sits at the bottom of an energy well.

To strip an oxygen atom off CO₂ to make Carbon Monoxide (CO), you must put a significant amount of energy back in. It is rarely "efficient" in terms of net energy (you lose more energy making the CO than you get back from burning it), but it is chemically possible and useful for creating feedstock gases.

⚠️ Critical Safety WarningCarbon Monoxide (CO) is an odorless, colorless, and tasteless gas that is highly toxic to humans and animals. It binds to hemoglobin in the blood 200 times more effectively than oxygen, leading to asphyxiation.

Do not attempt to generate CO outside of a professional laboratory with proper fume hoods and sensors.

The methods described below are industrial and academic processes, not for home experimentation.

1. Electrochemical Reduction (Electrolysis)

This is the method that most closely fits your description of "highly efficient methods to separate one Oxygen atom." Just as we can split water (H2O) into hydrogen and oxygen using electricity, we can split CO2.

The Process: You pump CO2 gas into an electrolysis cell containing a cathode (negative electrode) and an anode (positive electrode).

The Reaction: At the cathode, CO2 accepts electrons and splits:

CO2+2H++2e−→CO+H2O(Note: There are various reaction pathways depending on the electrolyte, but the net result is stripping oxygen).

The Tech: This requires specific metal catalysts (often Gold, Silver, or Copper) to lower the energy barrier. If the voltage isn't controlled perfectly, you often just get Hydrogen (from splitting the water in the electrolyte) or Formate instead of CO.

2. The Reverse Water-Gas Shift (RWGS)

This is the most common industrial method for turning CO2 back into CO. It is widely used in the production of "Syngas" (a mix of Hydrogen and Carbon Monoxide) for making synthetic fuels.

The Reaction: You mix CO2 with Hydrogen gas (H2) at high temperatures (often 300∘C to 1000∘C).

CO2+H2⇌CO+H2OHow it works: The hydrogen effectively "steals" the oxygen atom from the carbon dioxide to become water, leaving carbon monoxide behind.

Efficiency: This reaction is endothermic (absorbs heat). It requires a catalyst (often iron, copper, or ceria-based) and equilibrium shifts to work well.

3. Thermochemical Splitting (Solar Thermal)

This is a futuristic method that uses raw heat—often concentrated solar power—to brutally rip the oxygen atom off.

The Process: Metal oxides (like Cerium Oxide or Perovskites) are heated to extreme temperatures (approx 1500∘C) using concentrated solar energy.

Step 1: The heat forces the metal oxide to release some of its own oxygen, becoming "oxygen-starved."

Step 2: You introduce CO2. The oxygen-starved metal oxide rips an oxygen atom off the CO2 to replenish itself.

Result: The CO2 becomes CO, and the metal oxide is ready for the next cycle.

4. Photochemical Reduction (Artificial Photosynthesis)

This attempts to mimic plants. Instead of using chlorophyll, scientists use semiconductor materials (photocatalysts) that absorb sunlight.

How it works: When light hits the catalyst, it generates electrons that have enough energy to break the C=O bonds in CO2.

Current State: This is currently the "holy grail" of research but is not yet highly efficient. It usually produces a mix of Carbon Monoxide, Methane, and Formic Acid, rather than pure CO.

Summary Table

Method Inputs Mechanism Main Challenge

Electrolysis Electricity + Catalyst Uses electrons to break bonds High electricity cost; catalyst degradation.

RWGS Hydrogen + Heat Chemical substitution (H steals O) Requires expensive Hydrogen (H2).

Thermochemical Extreme Heat (Solar) Metal oxide oxygen exchange Material durability at 1500∘C.

Which is most "efficient"?Currently, the Reverse Water-Gas Shift (RWGS) is the most mature and "efficient" technology for large-scale production, provided you have a cheap source of Hydrogen. Electrolysis is the most promising for a direct "electric split" in the future, especially powered by renewables.

Would you like me to explain how these processes are currently being used in Carbon Capture and Utilization (CCU) to make e-fuels?

***

First, thank you for your review of various methods of making CO from CO2, and for providing insight about efficiency and risks. The context of the question is selection of the best (many factors are in play) energy storage system for transport and working vehicles on Mars. I am an advocate of Carbon monoxide and O2 as the very best possible combination of fuel and oxidizer, but members of the small international forum for which this report is prepared are advocates of many different approaches. The advantage of the CO/O2 method is that water is not involved, except that you have reported that water may be used as a part of the manufacturing process.

***

This is a significant distinction. If your goal is to advocate for a Carbon Monoxide (CO) / Oxygen (O2) economy on Mars, you are effectively arguing for a "Water-Independent" architecture. This is a strong strategic position because it untethers missions from the need to mine glacial ice, allowing vehicles to operate anywhere on the planet rather than just at the poles or specific craters.To support your report for the forum, here is the technical breakdown of how to produce CO without water, and an honest evaluation of its performance as a fuel source compared to the alternatives.

1. The Water-Free Method: Solid Oxide Electrolysis (SOXE)

You mentioned that I previously noted water "may" be used. That is true for Earth-based methods (like the Reverse Water-Gas Shift) which require hydrogen. However, for Mars, the "highly efficient" method you are looking for is Solid Oxide Electrolysis (SOXE).

This is the exact technology currently operating on the Mars Perseverance rover inside the MOXIE instrument.

The Mechanism: It uses a ceramic electrolyte (usually Yttria-Stabilized Zirconia) heated to ≈800∘C. When a voltage is applied, it electrochemically splits the CO2 molecule directly.

The Reaction:

2CO2heat+e−2CO+O2The "Water" Verdict: This process requires zero water. It uses only the Martian atmosphere (96% CO2) and electricity (Solar/Nuclear). The output is pure Carbon Monoxide fuel and pure Oxygen oxidizer.

Strategic Argument for your Report: Advocates of Methane (CH4) propulsion must find water ice to get the Hydrogen atoms (H). Advocates of CO/O2 propulsion only need the air, which is available at every valid landing site on the planet.

2. Efficiency & Performance Comparison

To defend CO/O2 against the other forum members (who likely support Methane/LOX or Hydrogen/LOX), you need to concede on energy density but win on logistical simplicity.

A. Rocket Propulsion (Specific Impulse)

The "miles per gallon" of a rocket is Specific Impulse (Isp).

Hydrogen/Oxygen: ≈450 seconds (The "Gold Standard," but hydrogen is hard to store).

Methane/Oxygen: ≈360 seconds (The SpaceX Starship choice).

Carbon Monoxide/Oxygen: ≈270−290 seconds.

The Trade-off: CO/O2 is a "weak" rocket fuel. You need roughly 30% more propellant mass to do the same job as Methane. However, because you don't have to mine water to make it, the energy cost of production (Total System Energy) can actually be lower for CO/O2 despite the lower engine performance.

B. Surface Vehicles (Internal Combustion vs. Fuel Cells)

For rovers and "working vehicles" (your specific context), CO is fascinating.

Internal Combustion: You can burn CO in a modified internal combustion engine. It burns slowly and is harder to ignite than gasoline, but it works. This allows for mechanical drivetrains without heavy batteries.

Solid Oxide Fuel Cells (SOFC): This is likely the winner. You can run the SOXE process in reverse. Feed the CO and O2 back into a fuel cell to generate electricity for electric motors. This creates a closed-loop regenerative power system (similar to a rechargeable battery, but using gas tanks).

3. The "Deep Cryogenic" Advantage

There is a subtle thermodynamic argument you can use to win over engineers:

Methane/Oxygen: Methane boils at −161∘C; Oxygen boils at −183∘C. They are close, but require different thermal management.

Hydrogen: Boils at −253∘C. It requires massive insulation and leaks through everything.

CO/Oxygen: Carbon Monoxide boils at −191∘C; Oxygen at −183∘C.

The "Magic" Ratio: CO and O2 have almost identical boiling points. This means you can store them in similar tanks with similar insulation, or even nested tanks, with much less thermal stress than Hydrogen systems.

Summary Table for your Report

Feature Carbon Monoxide / Oxygen Methane / Oxygen Hydrogen / Oxygen

Feedstock CO2 only (Atmosphere) CO2 + Water Ice Water Ice

Water Dependency None (Can be made anywhere) High (Restricted to poles/craters) Extreme

Rocket Efficiency (Isp) Low (~280s) High (~360s) Very High (~450s)

Storage Cryogenic (Easy, sim. to LOX) Cryogenic (Medium) Deep Cryogenic (Hard)

Primary Use Surface hoppers, rovers, return vehicles Heavy lift, ascent to orbit High efficiency upper stages

Next Step for your report: Would you like me to calculate the theoretical tank size difference for a standard Mars rover using CO/O2 versus batteries, to see if the "unlimited fuel" outweighs the bulk?

NASA MOXIE Explained This short video explains the MOXIE experiment on the Perseverance rover, which is the real-world proof of concept for the water-free CO/O2 production method you are advocating.

NASA has an Oxygen generator on Mars! How does it work?

Martian Wolf · 18K views

***

Thank you ** very ** much for your support for the CO/O2 fuel/oxidizer pairing! I should emphasize that the correspondence in play is intended to try to find the best possible combination of methods to support a Mars expedition and a settlement beyond. I would greatly appreciate your analysis of the unliquefied gas storage option. In your reply, you provided guidance that seems to assume that fuel and oxidizer will be liquefied before they are pumped into a vehicle or a tractor. I am wondering if a simple pressurized container might be able to hold enough fuel and oxidizer to complete a trip of reasonable length, or to perform work for a reasonable time. I would also offer an observation that there must be ONE of the many competing energy storage methods that is superior to all the others, when all factors are taken into account. For example, liquefaction requires energy input to perform the compression, and energy is wasted because thermal energy has to be delivered to the outside atmosphere. On the ** other ** hand, compressing gas to fill a tank has the same consideration, so there may not be a significant advantage. I suspect this topic is not one that lends itself to a quick solution, so I think everyone involved needs to take a deep breath, and prepare to do some hard work.

***

This is the exact type of "hard work" analysis that mission architecture requires. You are correct that we should not assume liquefaction is the automatic winner without checking the math. In engineering, we often find that the "low-tech" solution (pressurized gas) beats the "high-tech" solution (cryogenics) because of reliability and maintenance.Here is the analysis of Unliquefied Gas (High-Pressure) vs. Liquefied Gas (Cryogenic) specifically for the Martian environment.

1. The "Mars Ambient" AdvantageYou noted that on Earth, compressing gas is inefficient because it gets hot and you waste energy cooling it down. On Mars, we have a massive advantage: The planet is already a freezer.

Earth Ambient: ≈293 K(20∘C)

Mars Ambient: ≈210 K(−63∘C)

Because Mars is so cold, any gas you compress effectively behaves like it has been "pre-chilled."

Physics Check: Density is inversely proportional to temperature (PV=nRT). By simply sitting in a tank on Mars, CO gas is naturally ≈40% denser than it would be in a tank on Earth at the same pressure.

The Verdict: The "Unliquefied Gas" option is significantly more viable on Mars than on Earth.

2. The Density Fight (The "One Superior Method")

To determine if a "simply pressurized container" can hold enough fuel, we have to look at Energy Density. This dictates how big your fuel tank needs to be.

Liquid CO Density (1 bar,−191∘C): ≈790 kg/m3

Compressed CO Gas (350 bar,−60∘C): ≈400–450 kg/m3 (Estimated via supercritical fluid behavior)

The Trade-off: If you choose Gas Storage, your tanks will need to be roughly 2x larger (in volume) to hold the same amount of fuel as the Liquid option.

3. The "Tankage Penalty" (Mass of the Tank itself)This is usually where the "Compressed Gas" argument struggles.

Liquid Tank: Thin-walled (like a soda can). It only needs to hold low pressure (<5 bar). It is very light, but needs insulation.

Gas Tank: Thick-walled (Carbon Fiber COPV). It must withstand immense pressure (350–700 bar). It is heavy.

However, on Mars, the "Liquid" tank needs a refrigeration unit (cryocooler) to keep the CO from boiling (since Mars' −60∘C is still much hotter than CO's boiling point of −191∘C).

Analysis: If the weight of the heavy gas tank is less than the weight of the liquid tank + cryocooler + radiators, then Gas wins.

4. Application: "Work" vs. "Transport"

You asked about specific vehicle types. This is where the winner splits.

A. For "Working Vehicles" (Bulldozers, Excavators, Local Hoppers)Winner: Compressed Gas (Unliquefied)

Why: These vehicles work in short bursts and sit idle for days.

The Liquid Problem: If you leave a Liquid CO bulldozer parked for a week, the fuel boils off. You come back to an empty tank. You need constant power to keep it cold.

The Gas Advantage: A compressed gas tank can sit for 100 years and never lose a gram of fuel. It is "Instant On." For a tractor that drives 5km to a mine, digs, and drives back, the 2x tank volume is acceptable for the zero-boil-off reliability.

B. For "Long Haul Transport" (Long-Range Rovers, Ascent Vehicles)

Winner: Liquid (Cryogenic)

Why: Physics demands it. If you need to drive 500km, the sheer volume of gas tanks needed would make the vehicle massive. You need the high density of liquid to pack enough energy into a manageable frame. The "boil-off" doesn't matter because you burn the fuel faster than it warms up.

5. Thermodynamic Energy Balance (Your "Waste Heat" Point)

You correctly identified that both compression and liquefaction produce waste heat.

Liquefaction: You must cool CO from −60∘C down to −191∘C. This requires removing specific heat + latent heat of vaporization. It is energy-intensive.

Compression: To get CO to 350 bar, you must compress it in stages. This generates massive heat (>1000∘C adiabatically). You must cool it between stages (intercooling) or the compressor will melt.

The "Simplicity" Winner: Compression is thermodynamically easier. Making high-pressure gas is standard industrial tech. Making cryogenic liquid requires turbo-expanders and complex plumbing.

Conclusion for your Report

If you want to propose a "Superior Single Architecture," I suggest this compromise:

"Generate as Liquid, Store as Liquid, Deploy as Needed."

Produce the CO/O2 as liquid (highest density for the main storage farm).

When fueling a Rocket/Long-Haul Rover: Pump it as Liquid.

When fueling a Local Tractor: Pump it as High-Pressure Gas (allowing it to warm up and expand into the tractor's tanks).

This allows you to have one main refinery system, but gives the working vehicles the reliability of gas storage (no boil-off) and the transport vehicles the range of liquid storage.

Next Step: Would you like me to draft a comparison table of "Tank Mass vs. Fuel Mass" for a hypothetical Mars tractor to see exactly where the "break-even" point is between Gas and Liquid?

It is unlikely anyone will every read this report, so the clever recommendation for the fuel depot will be missed. This post will disappear from view in 24 hours and it will likely never be seen again.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here