New Mars Forums

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

Announcement

#2801 2025-03-12 05:15:33

- Calliban

- Member

- From: Northern England, UK

- Registered: 2019-08-18

- Posts: 4,291

Re: Politics

Robert, the problem is decay heat. A lot of that 3 months is spent waiting for decay heat generation to decline to levels where it is safe to depressurise the plant and begin fuel handling. This is why refuels tend to be included as part of a general overhaul period for the ship. The maintenance crew won't be sitting on their hands for those three months. They will be maintaining other areas of the ship.

It is possible to refuel at high decay heat, but risky. Heat removal will be heavily reliant on pumped flow using systems like ECCS. Any loss of power for pumped flow or loss of heat sink and the water covering the fuel will start to boil off. The higher the decay heat, the less grace time you have for water makeup. The safety case ends up being difficult and the more redundancy you need for things like power supply, the more expensive the operation becomes. This risk is probably why the Russians do what they do at sea. I am not familiar with their operations. But you may find they also have to wait for decay heat levels to decline, especially if they are removing fuel from water to some sort of dry storage. The refuel itself may take only 3 days, but the cooldown period preceding it will probably be measured in months.

"Plan and prepare for every possibility, and you will never act. It is nobler to have courage as we stumble into half the things we fear than to analyse every possible obstacle and begin nothing. Great things are achieved by embracing great dangers."

Offline

Like button can go here

#2802 2025-03-12 06:02:37

- Calliban

- Member

- From: Northern England, UK

- Registered: 2019-08-18

- Posts: 4,291

Re: Politics

The other option to consider is avoiding refuel altogether. This means building a whole-life reactor core. Design the core to last for the intended operational life of the ship and then scrap the whole ship when the core is depleted. At least one nuclear navy does this already. It means that maintenance periods are shorter and easier. When time comes to scrap the ship, there is no problem just laying up in a basin for a decade, letting decay heat decline to low levels before removing the fuel.

There are pros and cons to this arrangement. It is tricky to do. The problems with this approach are: (1) It tends to necessitate high burnup, which can cause fuel swelling or even bowing of fuel elements. This is less of a problem if using oxide fuels. (2) To avoid excessive burnup of the central core, it is necessary to zone fuel enrichment and include burnable poisons, so that power generation is flat across the core. That makes the core more expensive. (3) Core chemistry control is more important. The coolant will carry more soluble neutron absorbers to counteract the reactivity introduced by more heavily enriched fuel. The fuel cladding will be exposed to neutron flux and oxidative attack from radiolytic oxygen for much longer. So tight control of dissolved oxygen is necessary. (4) A whole life core is safer in some ways as there are fewer intrusive operations that can potentially disrupt decay heat removal. But the core also carries a greater liad of fission products making the consequences of an accident worse.

On balance, this is probably the best approach for your ice breakers. Their mode of operation exposes the hull to a lot of flexural and shearing stresses. So replacing the boat every 20 years with a new one isn't a bad idea. It allows your navy to avoud the costs of refuelling and reduces the need for heavy maintenance periods. Although 20 year lifespan means higher capital costs, a more regular build schedule achieves economies of scale and better quality control.

There are a number of ways that the Canadian Navy could do this. Canada never invested in enrichment capability, because the CANDU can burn natural uranium. A CANDU is a less desirable option for a ship because core volume is large and online refuelling would be difficult at sea. The uranium market is well established now, so Canada could simply buy enriched U from the US, Russia or Europe. Or it can develop its own enrichment capability. Not a huge problem, its just time and money. The other option would be to reprocess spent CANDU fuel and make MOX for your ship reactors. That would cost a bit more, but it also reduces the spent fuel stockpile and puts in place a technology that could support wider Canadian nuclear industry. If Canada has reprocessing, it is a service that US nuclear operators will probably be interested in buying. Especially if they start building things like the natrium fast neutron reactor. Nuclear engineering is an area where there could be a lot of cross border trade.

Last edited by Calliban (2025-03-12 06:19:12)

"Plan and prepare for every possibility, and you will never act. It is nobler to have courage as we stumble into half the things we fear than to analyse every possible obstacle and begin nothing. Great things are achieved by embracing great dangers."

Offline

Like button can go here

#2803 2025-03-12 15:26:25

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 8,449

Re: Politics

RobertDyck,

If Canada is serious about operating aircraft carriers while remaining within its limited military budget, then it should operate conventionally powered carriers that don't require spending any precious defense dollars on all the support activities required to operate naval nuclear reactors. There's no clear military justification for nuclear power on surface warships, unless all the ships in the battle group are nuclear powered, because an aircraft carrier would never leave its escorts behind. Nuclear power is an extravagance that most nations cannot afford. Since all the other ships in the battle group and the aircraft themselves are still conventionally powered, adding nuclear reactors to the carrier doesn't economize on very many underway refueling events.

The high fuel burn rates associated with historical conventionally powered American aircraft carriers were due to the poor thermal efficiency of WWII era steam boilers, which was about 16.5% according to empirical data collected for speeds of 20 knots and 30 knots from the Kitty Hawk class, which were the last class of conventionally powered American aircraft carriers. Modern gas turbines, such as the latest versions of the LM2500, when run at max output / max thermodynamic efficiency, fall between 36% and 39%. Supercritical CO2 gas turbines would be 50% thermally efficient.

Kitty Hawk class cruising range / operating hours at 20 knots / 23mph, by propulsion plant technology:

Foster-Wheeler or Babcock and Wilcox Marine Boilers: 13,800 statute miles (600 hours)

LM2500s: 30,109 statute miles (1,309 hours)

Supercritical CO2 gas turbines: 41,818 statute miles (1,818 hours)

Kitty Hawk's longest operational deployment covered 62,000 statute miles. That means you'd need to refuel the ship once per 6 month deployment, or perhaps never if you only deploy your carriers for 3 months.

If Canada operated navalized variants of Textron AirLand's Scorpion, equipped with the latest sensors and weapons, they'd have more real combat power than most other navies. These fighters would be drastically cheaper to operate than all the heavy fighters operated by other western navies, so several squadrons could be purchased and deployed. Their simplicity, economy of operation, and range matters a lot more than how fast they are. The Scorpion is a twin-engine subsonic ISR / attack jet with 2 crew members and an internal weapons bay. Naval fighters benefit greatly from the ability to loiter at significant distances from their carrier. Modern heavy fighters cannot loiter for any significant period of time because they require so much power to remain aloft.

Numbers of combat jets matter far more than theoretical capabilities. In real life you launch with 2 primary weapons to perform your mission, because that's what you can land with. If you can launch with a pair of 2,000 pound class munitions and 2 to 4 defensive missiles, that's as heavy a loadout as you need. Anything more than that rapidly becomes impractical nonsense.

Let's say you field 2 air wings with 48 Scorpions per air wing, and deploy with half of the air wing at any given time on 3 month deployments, so you deploy twice per year. Let's assert that 18 of the 24 jets can fly each day on a single 4 hour mission.

18 jets * 4 flight hours per day * 130 flight ops days per year * $3,000 per flight hour = $28.08M per half air wing per year

Each crew receives approximately 390 hours of operational flying from the carrier per year (similar to the number of hours our squadron's air crews were accumulating during Operation Enduring Freedom), plus maybe 50 to 70 hours of flying back at a naval air station for recurrent training / work-ups. That makes them highly proficient aviators in at least one mission area, with enough spare flight hours for a secondary specialty, because they're getting a lot more hours than virtually any other western flight crews receive during peace time. All of this is possible because Canada selected a fighter with modest CPFH, so the money saved on airframe maintenance can instead be devoted to far more training hours with high quality sensors / weapons.

$56.16M per air wing per year, or $113.32M total cost to maintain 2 carrier mobile air wings. That's the purchase price for 1X F-35C, but instead of spending that amount of money merely to purchase stealthy heavy fighters, you're fielding 2 complete air wings embarked aboard 4 CATOBAR aircraft carriers deployed over non-consecutive 3 month deployment periods per year to increase sailor retention and to reduce the toll exacted on the equipment that would otherwise be associated with 6+ month deployments. There should also be fewer problems with complacency killing people. Around the 3 to 4 month mark, the younger American sailors seem to become complacent to the danger they're in on the flight deck. Maybe Canadian sailors are different, but I doubt it. This is mostly a "young man" problem.

Since the carriers are conventionally powered, one ship can have a skeleton crew aboard while in-port undergoing repairs / refurbishment while the other carrier is at sea. That provides 24/7/365 at-sea defense of the Atlantic and Pacific Canadian coastlines, in order to get between any potential aggressor and the Canadian homeland. If Canada has something equivalent to a Defense Logistics Agency, those are the people who would be refurbishing the carrier in port, so that most of your sailors can fully crew the operational carrier.

One of the key features of conventionally powered carriers is that you truly can "walk away" from them if you need to. If one of the four carriers requires complex overhaul, that ship doesn't need her crew present to babysit the reactor. There is no such thing as walking away from a nuclear powered ship. You're married to her.

If you're smart about how you design the electronics suite and defensive weapons, the possibility exists for anything classified to be entirely removed from the ship and stored separately, such that even fewer crew members need to remain aboard, perhaps limited to a handful of engineering officers overseeing the repair activities. At that point, it's functionally no different from a civilian ship. If the officers and a yard crew need to take her out for a shakedown, they can do that with minimal fuss.

Minimal complexity that doesn't sacrifice real combat capability is the name of the game here. You get 2 limited capability carrier battle groups that have the most important features of an American blue water carrier battle group, at a fraction of what America pays for the pointless techno-gadgets that may have some theoretical advantage in some specific scenario, but aren't doing much for anyone at all other times.

AIM-174 - Fleet air defense against sea-skimming and ballistic missile threats

AIM-120 - General purpose air superiority

AIM-9 - Defensive missiles

JDAM-ER - Precision all-weather stand-off bombing with data-link

Harpoon / SLAM - All-weather stand-off anti-ship or land attack cruise missiles

AARGM-ER - Stand-off anti-radiation missile for SEAD

Bay-mounted ISAR Pod - Organic mini-AWACS capability

Bay-mounted Camera Pod - Organic photo-recon / bomb damage assessment capability

I think that provides a good mix of capabilities that cover most missions an air wing attached to a limited capability carrier battle group could realistically be tasked to perform. The weapons selected are adequate for their intended use cases. No specialty weapons such as Hellfire or APKWS or SDB or bunker busters were included because they're inappropriate for a blue water naval force primarily focused on interdicting enemy bombers, tactical fighters, and ships, with the odd land-based target of opportunity that may appear. You can still clobber the snot out of any tank with a JDAM. It's cheaper than a Hellfire, can potentially fly much farther, and there won't be much left after it hits. It will require off-board data link guidance to hit a moving target, but it works.

Online

Like button can go here

#2804 2025-03-12 18:11:32

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 8,449

Re: Politics

RobertDyck,

US DLA FY2024 list price for F76 diesel / distillate fuel for ships, is $3.54 per gallon:

Defense Logistics Agency - Standard Fuel Prices in Dollars - FY 2024 Budget Estimate - Fuel Short List - FY 2024 Fuel Price

Over 50 years, all 4 carriers would burn approximately 1.2 billion gallons of F76 marine fuel oil, which works out to $4.248B, or $84.96M USD per year.

Ignoring refueling costs, the price to construct and decommission the pair of reactors for an aircraft carrier works out to around $2B USD per ship, using costing figures from 28 years ago. I can promise you that it costs more money now.

LIFE-CYCLE COSTS FOR NUCLEAR-POWERED AIRCRAFT CARRIERS ARE GREATER THAN FOR CONVENTIONALLY POWERED CARRIERS

A nuclear-powered carrier costs about $8.1 billion, or about 58 percent, more than a conventionally powered carrier to acquire, operate and support for 50 years, and then to inactivate. The investment cost for a nuclear-powered carrier is more than $6.4 billion, which we estimate is more than double that for a conventionally powered carrier. Annually, the costs to operate and support a nuclear carrier are almost 34 percent higher than those to operate and support a conventional carrier. In addition, it will cost the Navy considerably more to inactivate and dispose of a nuclear carrier (CVN) than a conventional carrier (CV) primarily because the extensive work necessary to remove spent nuclear fuel from the reactor plant and remove and dispose of the radiologically contaminated reactor plant and other system components.

Life-Cycle Costs for Conventional and Nuclear Aircraft Carriers (based on a 50-year service life)

(Fiscal year 1997 dollars in millions)Cost category CV CVN

Investment cost

Ship acquisition cost $2,050 $4,059

Midlife modernization cost $866 $2,382

Total investment cost $2,916 $6,441

Average annual investment cost $58 $129

Operating and support cost

Direct operating and support cost $10,436 $11,677

Indirect operating and support cost $688 $3,205

Total operating and support cost $11,125 $14,882

Average annual operating and support cost $222 $298

Inactivation/disposal cost

Inactivation/disposal cost $53 $887

Spent nuclear fuel storage cost n/a $13

Total inactivation/disposal cost $53 $899

Average annual inactivation/disposal cost $1 $18

Total life-cycle cost $14,094 $22,222

Average annual life-cycle cost $282 $444

Tell me if you think Canada can afford costs like those, or if you think your nation's money is better spent on conventional alternatives that provide like-kind capabilities for a lot less money. Whenever you don't have an unlimited amount of funding that you're willing to devote to any single national priority, you become very shrewd about analyzing costs, and then you make pragmatic decisions that give you both capabilities and costs that you can live with.

Operating an aircraft carrier is never going to be cheap, but an air base that can be wiped off the map in a single surprise attack is pennywise pound-foolish. Mobile airfields have their place in a modern military, just as tanks and infantry rifles do.

While contemplating what the RCN could do if they had real aircraft carriers, also think through what the RCAF might be able to accomplish with pure air power, provided that their jets had the range and missile tech required. Any good military strategist considers all practical options before choosing a course of action. Naval air power may or may not be the most practical option for Canada.

First, develop a solid concept of operation for how Canadian defense against surprise attack should work. Identify the likely adversaries, avenues of approach they would take during a sneak attack, and then evaluate what they're most likely to be equipped with. From that exercise stems fighting doctrine, which informs purchasing decisions regarding the equipment, tactics, and training necessary to apply the fighting doctrine, pursuant to the concept of operation for a Canadian defense force.

Online

Like button can go here

#2805 2025-03-12 19:11:36

- RobertDyck

- Moderator

- From: Winnipeg, Canada

- Registered: 2002-08-20

- Posts: 8,362

- Website

Re: Politics

The OK-900A reactor on Arktika class icebreakers has a reactor core that can be lifted out by a crane. No cutting the hull. A series of hatches above the reactor to the topside of the ship. The reactor fuel is the bottom of a module that is lifted out by crane. No cutting, just open several hatches, and use a crane to lift it out. The spent fuel rod is placed in a radiation shielded containment sleeve. This makes refuelling less expensive and faster.

Yes, I would design a Canadian reactor inspired by the Russian one, but not exactly the same. Canada owned/operated 2 light carriers after WW2. When they wore out, Canada owned/operated 1 light carrier until 1972. That was controversial: it went through a major mid-life refit, then was immediately scrapped. Why scrap it after spending money for a refit? That decision was made by Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, Justin Trudeau's father. My point is yes, we could afford 1 aircraft carrier battle group. One. Just one. Not a light carrier, a full carrier with twice the displacement of a light carrier. Yes, with a nuclear reactor. Also realize Canada has committed to increase military spending from 1.36% of GDP to at least 2%.

Offline

Like button can go here

#2806 2025-03-13 13:44:30

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 8,449

Re: Politics

RobertDyck,

I'm not sure what you had in mind, but a ship the size of a super carrier would require 8 OK-900A reactors to provide 208MW of propulsive power. The 8 reactor compartments carried by Enterprise weighed about 13,208t. To that figure you must add the weight of the geared steam turbines. 4,000,000 gallons of F-76 weighs about 12,882t for reference purposes. Unlike a nuclear reactor, that weight will be situated in the lowest portion of the ship's hull, where it aids in maintaining stability in rough weather. Most or nearly all of Enterprise's reactor weight was situated below the waterline, so that's good, but still not as good as fuel in the fuel bunkers. At least some ships of the Nimitz class, interestingly enough, have a slight list due to a weight distribution problems, although I don't think the reactors were the cause of the list, but I can't recall.

USS Nimitz covered 100,395 statute miles during 321 consecutive days at sea while the COVID pandemic was in full swing. To the best of my knowledge, that represents the greatest total number of miles covered during a single carrier battle group deployment. There was every incentive to minimize at-sea replenishment activities to slow or prevent the spread of COVID.

100,395 / 7,704 hours = 13.0315mph / 11.332 knots <- average speed of travel

Q: Why did USS Nimitz travel at that speed?

A: Her escorts don't have nuclear power, so she had to deliberately keep her speed slow enough that her escorts wouldn't require constant fuel replenishment.

At that cruising speed, a SCO2 powered Kitty Hawk class aircraft carrier would burn 2,355,241.2 gallons of fuel, or a little more than half of her 4,000,000 gallon diesel fuel load. The historical steam boiler powered Kitty Hawk class would burn 7,065,723.6 gallons of fuel, so she would require at least one UNREP event to replenish her fuel oil bunkers, probably two since they don't like it when the ship's fuel load drops below 50%. That said, if you have SCO2 power and you're going to travel that slowly, then the carrier doesn't need any fuel replenishment for a very long time.

My brain still understands how to count, so it can't concoct a reality-based scenario where a carrier either leaves all her escorts behind to prove that she can sail off at 30 knots ('cause nuclear power, man!), and it also understands that making every ship in the battle group nuclear powered is a total non-starter on cost alone. If I'm more than doubling the cost of the carrier, then I want to know what it is that I'm actually "saving" by switching to nuclear power. I have a capability I cannot use for double the cost of the alternative. Maybe that made perfect sense to Admiral Rickover, but it makes no sense to me, because I'd rather have 2 CV-63s (with drastically more efficient propulsion) for the price of 1 CVN-68. I can purchase 7 CV-63s for the price of 1 CV-78. There is no capability that 1 CVN-78 possesses which makes it worth the price of 7 CV-63s.

During operation "prove that a nuclear ship doesn't require at-sea fuel replenishment", aka "Operation Sea Orbit", in 1964, USS Enterprise, USS Long Beach, and USS Bainbridge (all nuclear powered) sailed 30,216 miles during 57 consecutive days at sea, which means their speed was 22.09mph, or slightly less than 19.21 knots.

Could a SCO2 powered Kitty Hawk class sail at 19 knots for 1,368 hours without fuel replenishment?

Basic math says it could, for a lot less money.

What, then, is the actual point of having a singular all-nuclear carrier battlegroup or a battlegroup where only the carrier is nuclear powered?

Sea Orbit was a theatrical stunt concocted by Vice Admiral John S. McCain, Jr, who wanted to "prove" that nuclear powered ships don't require replenishment oilers. This is facially absurd, though, since all the aircraft were still powered by jet fuel. No actual warfighting capability is added by such stunts. While those ships were all quite capable for their era, leaving your sub chasers and radar picket ships behind is a better than average way to get your carrier sunk.

What military problem are you solving for by equipping a singular ship with a nuclear reactor?

Edit:

Apologies, RobertDyck, but I used the fuel burn rate data for the wrong ship in my above calculations. It was late when I first wrote that and I had a headache. I realized my error almost as soon as I posted it, but decided to leave it there. My data comes from a research paper from the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, entitled "Predicting Ship Fuel Consumption: Update, by David A. Schrady, Gordon K. Smyth, Robert B. Vassian, July, 1996". The code for the paper is "ADA313847.pdf".

Kitty Hawk's historical burn rate at 11.1 knots was 2,482gph, so a SCO2 power plant would burn approximately 827.33gph, which means 4,835hrs of plant operation at 13.0315mph. That implies 63,004 statute miles of range, so 1 UNREP even to replenish the ship's fuel bunkers would be required to travel 100,395 statute miles at 13.0315mph, using a SCO2 power plant. Even so, I think that accurately illustrates how silly the "range anxiety" problem is. When Nimitz made her record deployment, she did take on fuel for her air wing many times, though, so the idea that a nuclear powered ship requires no fuel replenishment remains a fantasy. There is no such thing as operating a super carrier (as a mobile airfield) without underway fuel replenishment.

Last edited by kbd512 (2025-03-13 17:05:31)

Online

Like button can go here

#2807 2025-03-13 23:35:35

- RobertDyck

- Moderator

- From: Winnipeg, Canada

- Registered: 2002-08-20

- Posts: 8,362

- Website

Re: Politics

The Canadian carrier idea probably will never happen. But to answer your question, I was thinking of 40,000 metric tonne displacement. The last Canadian carrier was Bonaventure, a light carrier at 20,000 tonne. Britain considers a "full" carrier to be 40,000 tonne. The French carrier Charles de Gaulle is 42,500 tonne. But an American supercarrier is 100,000 tonne. The Russian icebreaker "50 Let Pobedy" was the last and largest of their nuclear icebreakers, still in service, 25,168 tonnes. It has 2 OK-900A reactors, so a Canadian icebreaker aircraft carrier should work with 3 or 4 such reactors. The cube-square rule applies to ship design. Volume increases as the cube of the length of a ship, and mass (weight) increases directly with volume. However, surface area of the hull increases as the square. Drag is proportionate to surface area, so the larger the ship the more efficient it is.

Each OK-900A produces 171 megawatts thermal, the pair of reactors delivers 54 MW at the propellers. An American Ford class supercarrier has 2 A1B reactors, each of which produce 125 megawatts (168,000 hp) of electricity, plus 350,000 shaft horsepower (260 MW). That's estimated, the Wikipedia article took specs from the A4W and added 25%. That's enough power to operate all 4 propellers from just one reactor.

Yes, one of the features I suggested was a "dual acting hull". That means a hurricane bow at the front that cuts through the waves like a knife. That permits operation in deep seas during a bad storm, including a hurricane. Instead of a squared off stern, an icebreaker bow. So when the ship encounters ice, it just turns around a drives backward. Ships like this are already built. Finland designed a new, more efficient, icebreaker bow. "50 Let Pobedy" uses it. An icebreaker bow is rounded to slide onto the ice like a sled, use the weight of the ship to break ice. An icebreaker bow is not safe in deep ocean in heavy seas, so...both. They use azimuthing pods for propulsion. Propellers have to be deliberately designed strong enough to chop up ice.

Arktika-class icebreakers can break 2.2 metre thick multi-year ice. "50 Let Pobedy" can break 3.0 metre multi-year ice. Due primarily to its new bow. The ship needs a lot of power to break that ice.

Hmm, let's see. Charles de Gaulle has a beam at waterline of 31.5 m. "50 Let Pobedy" has a beam of 30 m. Could a Canadian aircraft carrier get away with 2 reactors? I did say they would use a new Canadian design inspired by the Russian one. Perhaps a bit more power per reactor?

Offline

Like button can go here

#2808 2025-03-14 11:01:22

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 8,449

Re: Politics

RobertDyck,

The smaller French aircraft carrier, Charles de Gaulle, may not require refueling at-sea, but they only have 45 days of food onboard, so irrespective of whether or not they need to refuel, they still require UNREP every 2 weeks or so to remain at sea for any significant period of time, even when they're not burning any jet fuel by conducting flights ops.

I consider 40,000t to be the lower limit for useful aircraft carrier capability when operating at least 3 squadrons of jet aircraft, although 60,000t provides significant better capability, and an 80,000t to 110,000t full load displacement provides full super carrier capabilities, because the mass allocation increase allows the carrier to be large enough to store significant amounts of food, fresh water, fuel, aviation ordnance, spare parts, and of course, multiple squadrons of jet aircraft. Smaller aircraft carriers make a lot more sense if the aircraft are smaller and burn less fuel. That is why I suggested repurposing Textron AirLand's Scorpion. If heavy fighters will be operated, then you really need a larger carrier. The Phantom, Tomcat, Rafale, Super Hornet, Lightning II, various navalized Flanker derivatives produced by Sukhoi or Shenyang, and the new Shenyang J-35 are all heavy fighters which require extreme logistical support. I use the term "heavy fighter" to describe any fighter aircraft with a MTOW similar to or greater than a Boeing B-17 or Consolidated B-24 bomber from WWII, both of which had MTOWs of 65,000lbs. The Scorpion's MTOW is 22,000lbs, so it's literally a third of the weight of those other fighters.

Fully laden modern combat jets are around 1/3rd fuel by weight, because they have to be, as a function of their extreme weight and the requirement for extreme amounts of thrust to push them through the air. A B-17 or B-24 carries a similar number of gallons of internal fuel to a heavy fighter, and their cruising range with a modest ordnance load is remarkably similar, even though they travel at slower speeds. This is an indicator that you can do lots of things to optimize aerodynamics when you have a high thrust-to-weight ratio power plant and optimized airframe, but you're not going to "cheat" basic flight physics. Carrying a given payload to a specific distance, whether done using lower speeds / larger airframes / less engine power or much smaller airframe (reduced wetted area) with far greater engine power, your total fuel burn for an optimized airframe and flight profile is remarkably similar across WWII radial piston engines to turboprops to primitive turbojets to modern afterburning turbofans. Modern fighter jet climb rate / turn rate / acceleration performance greatly exceeds that of a B-17, but you end up burning just as much fuel as a WWII era strategic heavy bomber to achieve that performance.

The net net is that operating the consumption-equivalent of WWII era strategic heavy bombers off of aircraft carriers either requires a lot of fuel and space to put those heavy fighters, or very few jets can be carried. I feel like the ship size comparisons below will provide a visual perspective regarding how large of a ship we're talking about.

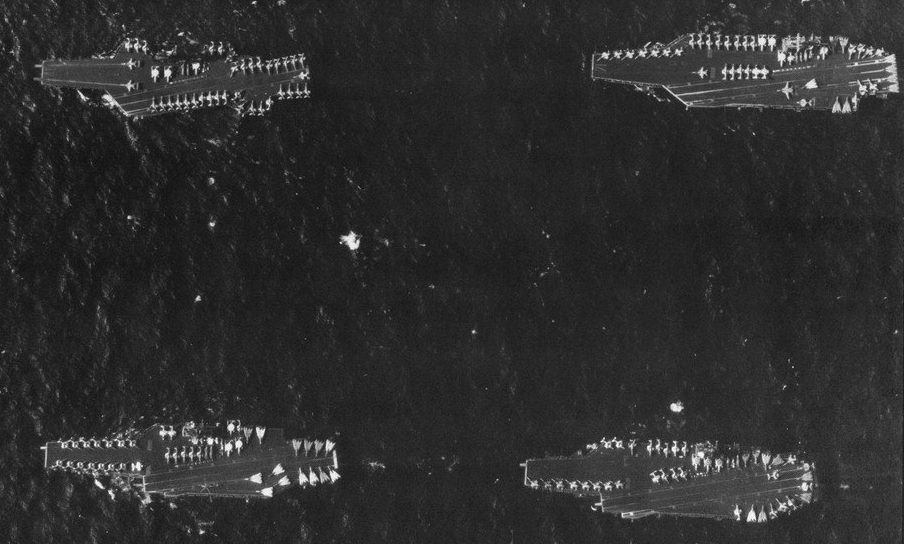

USS Enterprise (CVN-65) and Charles de Gaulle steaming in the Med, for size comparison purposes, 16 May 2001:

USS John C. Stennis (CVN-74), USS John F. Kennedy (CV-67), Charles de Gaulle, and HMS Ocean, 18 April 2002:

This is what the French are planning to build to replace Charles de Gaulle (75,000t full load displacement):

What the world thought of as "the first super carriers" (the Forrestal class), were in fact the smallest ships realistically capable of extended duration blue water operation.

USS Forrestal (CV-59), 31 May 1962:

USS Kitty Hawk (CV-63), 23 April 1964:

USS Harry S. Truman (CVN-75) and USS Gerald R. Ford (CVN-78), 4 June 2020:

Edit:

For comparison purposes USS Midway (CV-41), as she appeared in 1945 (45,000t), 1957, and 1970 (64,000t):

The Midway class carriers were generally thought of as poor blue water carriers (their bows were frequently drenched with salt spray unless the sea was calm), a function of too little freeboard (distance between the waterline and the flight deck). Their internal volume and displacement was insufficient to provide similar capabilities to the Forrestal class. The US Navy operated them for so long because replacement super carriers competed with other dubious spending priorities (nuclear powered carriers) and they already had 3 Midway class carriers in service. The Midway class embodied what the 24-ship Essex class carriers should have been. If the Essex class had not been so limited in upgradability, it's probable that the Navy would've continued to operate those carriers until the Cold War ended, with various mid-life upgrades and refurbishment activities taking place over the decades of service. Quantity has a quality of its own, so if we had built 32 Midway class carriers, there'd be little need for the follow-on classes (Forrestal, Kitty Hawk, Enterprise, Nimitz) of super carriers. We built 19 of those super carriers. 32 upgraded Midway class carriers could've provided like-kind capability, probably for a lot less money, at least until the Cold War ended.

USS Midway (CV-41, Midway class, top left), USS Teddy Roosevelt (CVN-71, Nimitz class, top right), USS Ranger (CV-61, Forrestal class, bottom left), USS America (CV-66, Kitty Hawk class, bottom right), 2 March 1991:

Last edited by kbd512 (2025-03-14 12:15:03)

Online

Like button can go here

#2809 2025-03-14 18:48:40

- RobertDyck

- Moderator

- From: Winnipeg, Canada

- Registered: 2002-08-20

- Posts: 8,362

- Website

Re: Politics

As I said, it's unlikely Canada will build an aircraft carrier. Why have a mobile air base when a stationary one is less expensive, less vulnerable, and Canada doesn't invade other countries? More likely is my proposal to re-commission the former Canadian air force station at Resolute. The station was converted to a commercial airport for the nearby town, so the runway is still there. With mid-air refuelling, CF-18 Hornet patrol range is the entire arctic. Right now one politician (Mark Carney) is talking about bases at Iqaluit, Yellowknife, and Inuvik. In another interview he said locations are not set, one possible location is Tuktoyaktuk. Leader of the other major party (Pierre Poilievre) is talking about Iqaluit, as well as 2 new navy heavy icebreakers in addition to the already ordered 2 icebreakers for the coast guard. Poilievre also mentioned retaining the coast guard base at Nanisivik. I think Nanisivik is a very poor location and poorly equipped, so dismantled it and rebuild at Resolute. There are several paths through the northwest passage, but all paths must go past Resolute. So Resolute can defend that shipping lane. And Resolute is farther north than any other mentioned locations, so better to defend the Canadian arctic.

Distance from Resolute to the northern coast of the most northern Canadian island is 1,100 km. To the southwestern point of the most southwestern of the arctic islands is 1,020 km. To the most eastern point of Devon Island is 440 km. From Resolute to Iqaluit is 1,600 km. Canada has 5 CC-130 Hercules aircraft fitted out as mid-air refuelling tankers, and 2 CC-150 Polaris (Airbus A310-300) also fitted for mid-air refuelling. On order are two CC-330 Husky (Airbus A330) with 4 more to be ordered later. Currently the Hercules are used in the north, Airbus are used for trans-oceanic flights.

Offline

Like button can go here

#2810 2025-03-14 19:12:58

- RobertDyck

- Moderator

- From: Winnipeg, Canada

- Registered: 2002-08-20

- Posts: 8,362

- Website

Re: Politics

kbd512, you have argued for American supercarriers because you're familiar with them. As I said, if (if if if) Canada were to acquire an aircraft carrier, it would have to be smaller. Canada did operate 2 light carriers from 1946 to 1957, purchased from Britain. When they wore out, they were replaced by one updated light carrier 1957-1970. But again, why? In the age of mid-air refuelling, and considering Canada can use air bases on land of any of Canada's allies, and the only places Canada would operate is either Canadian soil, Canadian coast, or one of Canada's allies, do we need a carrier? Wouldn't air bases in Canada's north make more sense? Still, it's fun to plan.

So I drew up a "back of the napkin" design. One flight deck used for both launching and landing, so the ship could not launch and land at the same time. Instead focus on changing from landing to launching very quickly. Length of the runway equal to the angled flight deck of an American supercarrier, either Nimitz or Ford class. That would allow all aircraft that can operate on an American carrier to work on this one. Maximum use of automation to reduce ship crew. While an American carrier has 3 squadrons of light fighters (Hornets) and 1 squadron of heavy fighters (Super Hornets), the Canadian one would carry 4 squadrons of light fighters (Hornets). Designed so the Hornets could be replaced by F-35C. Instead of 4 E-2D Advanced Hawkeye aircraft, 4 UAVs with the same electronically scanned radar. Instead of 4 EA-6B Prowler aircraft with electronic warfare, 4 UAVs with a single electronically scanned jammer (phased array). Instead of 2 C-2 Greyhound cargo aircraft, 2 Dash-8 cargo aircraft to use the same hinge to fold wings as the Greyhound. No space in the hanger for the Dash-8, just deck plane. In case of an arctic storm, the Dash-8 could fly to a nearby airport on land. Instead of 8 Seahawk helicopters, 7 CH-148 Cyclone helicopters.

Offline

Like button can go here

#2811 2025-03-15 04:26:49

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 8,449

Re: Politics

RobertDyck,

Why have a mobile air base when a stationary one is less expensive, less vulnerable, and Canada doesn't invade other countries?

If China or Russia conducted a sneak attack against Canadian air bases, then they might destroy aircraft sitting on the ground there, or at least immobilize them by cratering the runway they require to takeoff and land, before an effective defense or counter-attack can be mounted. After Canada's air assets are either destroyed on the ground or otherwise rendered inoperative for lack of a runway to operate them from, even a purely defensive response becomes more difficult. Did you pay attention to what the Russians did to Ukraine's air bases at the outset of the war? If the destruction of Ukrainian air bases was not enough of a wake up call, then how about the damage done to Israeli and Iranian air bases?

A stationary air base is not nearly as difficult to attack as a mobile air base. Air bases remain exactly where they were from the time they were built until the time they're closed, so finding one only requires a small observation satellite or an airborne radar sensor aircraft, which could be located hundreds of miles away if it's at high altitude. Land based long wavelength over-the-horizon radars possessed by Russia and China can also create target images of our air bases. You don't need expensive guidance electronics and sophisticated onboard sensors to launch a weapon against a fixed point on the surface of the Earth. The moment your target is mobile and can be relocated to a different ZIP code inside of 30 minutes, the sophistication of both the target detection / tracking solution and the weapons used to conduct a successful attack goes up exponentially. To successfully attack an airbase, a ballistic missile or glide bomb using purely inertial guidance is sufficient. The cost of glide bombs is about equal to 155mm artillery shells. The ballistic missiles are obviously more expensive, but the speed of the attack is much greater, so there's less time to defend against it. To attack a carrier battle group, you need cruise missiles with radars or imaging infrared sensors, off-board inertial guidance delivered via jam-resistant data links, and remote airborne or satellite sensors capable of finding and tracking the carrier. That is far easier said than done. If you knew a carrier's last position, as of 15 minutes ago, that's not good enough. If the carrier was moving at only 20 knots, then it's already 5.75 statute miles away from the position where it was last spotted. The carrier could be anywhere within an 8.625 mile radius if it was moving at 30 knots.

The counter-argument in favor of large air bases is that they can and typically do launch more sorties per day, in comparison to a super carrier. That is especially true for the US Air Force, but only because they have as many or more aircraft stationed there as can be carried aboard an aircraft carrier, aerial refueling tankers, labor-saving devices for rearming planes which are not present aboard a carrier, a host of other aviation support assets such as ISR and CSAR, and defense-in-depth of said air base, which is largely provided by the Army (Patriot and THAAD) or Navy (the AEGIS Combat System has the ability to guide any weapon from any ship using data links, namely SM3 / SM6 / ESSM / RAM, and the fully integrated electronic warfare suite used to jam or decoy inbound missiles). This is great for the US Air Force, but the last time they operated in contested air space was the Viet Nam War, and numerous aircraft were destroyed on the ground by surprise artillery barrages. The runways were also cratered. They were repaired, but that took time. Meanwhile, the Navy and other air bases had to provide air support to help repel the attack while repairs were effected. The air base in question was defended by SAM batteries, but those weapons were useless against incoming artillery shells. Canadian air bases may be located far enough inland to prevent that kind of simplistic attack from being effective, but that also means they're far enough away that immediate retaliation is not an option.

Fighter aircraft like the Hornet or F-35 are small enough to store in hardened aircraft shelters with their ground support equipment. I've never seen hardened shelters for aerial refueling aircraft. B-2s get their own shelters because there's only 20 of them and they're strategic assets. Maybe Canada could do something similar for their tanker fleet, but will they? I'm sure more and larger shelters could be built, but at that point we're talking about serious money being sunk into air bases so-equipped. If SAM batteries and facilities hardening don't grant near-immunity to an attack, that's a serious problem. The point is, you're never going to get a "cheap but good" solution. The solution will always be a major compromise so as to be cost-justifiable by your politicians.

At a more fundamental level, do you think Canada has sufficient air power to stop surprise Russian and Chinese attacks (from something as simplistic and low-cost as a mass drone barrage launched from a Russian container ship in response to Canadian support for Ukraine)?

The Israelis and Americans ran out of missiles to intercept the barrage of missiles and drones launched by Iran. If Iran had the resources of Russia or China, they could launch waves of attacks, as-seen in Ukraine, and then all the previously defended air bases and cities start getting hit because there are no interceptor missiles left. That has happened numerous times to both the Ukrainians and Russians. They have an effective defense until the missiles run out, and then the lack of AAA assets means there's not even an effective point-defense to backstop running out of missiles. In the mass attack launched by Iran, American Eagles scrambled to intercept resorted to firing their cannons after they ran out of Sidewinders and AMRAAMs, which they immediately stopped doing because when the drone or missile warheads detonated from being struck by the 20mm cannon shells, they spread shrapnel in the flight path of the Eagles. The risk of "shooting yourself down" was too great for that tactic to be effective.

The real lesson to be learned there is that AAA cannons for air bases and ships are not a "dead technology" as a means of effective point defense, because modern radar-guided AAA has been shown to be a viable interception tool when used against comparatively cheap and slower drones and missiles. The Shahed 136 drone can deliver a 50kg warhead to a distance of about 1,600 miles. That means anybody with a cargo container ship could feasibly launch hundreds of them at an air base, and some of them will inevitably make it through the missile defenses and fighter patrols.

Asserting that the US will help is to ignore the timeline for an effective response to be mounted. It takes at least 4 to 6 hours for aircraft to be scrambled in numbers from US air bases, 24 hours for carriers to be deployed from naval bases in CONUS, so the attack is likely to have already destroyed whatever air assets Canada has, before any reinforcements show up. In short, there's no "magic button" that America can press to fight back if the attack occurs more than a thousand miles from the nearest friendly units. As such, any allied nation which values its own military had better make sure that they can at least repel an attack long enough for help to arrive. If we have some inkling that an attack is likely, then of course we'll try to pre-position assets to intercept, but that typically only works against known military assets like Russian Tu-95 bombers and their warships.

If Canada did have carriers, of whatever size Canadian military experts deem most appropriate, and enough of them were built to keep at least 2 deployed at-sea at all times, the timeline for an effective counter-attack is considerably reduced, to the point that the Russians or Chinese are far less assured of being able to effectively "ground" Canadian air assets when they're needed most. America has so many military assets, spread over such a large area, that the results from a surprise attack doing much more than steeling American resolve to lay waste to the attacker is non-existent.

As 9/11 and Pearl Harbor proved, if you're willing to die for your cause, you absolutely can successfully attack America in a big and highly destructive way, but you should fully expect that any military capabilities you had will be reduced to near-zero afterwards, irrespective of how long that takes or how costly it proves to be. Despite that simple fact of history, our reaction has never been an effective deterrent against attacking America.

These are the real military capabilities aircraft carriers confer that air bases do not:

1. To generally forego the destructive results of a surprise attack by being mobile and therefore unpredictable

If you had 4 light carriers and all of them were in different physical locations, there's probably not a realistic attack scenario which can disable or destroy all of them at or near the same time.

2. To rapidly strike back against an attacker following a surprise attack

Swiftly "returning the favor" is an under-appreciated aspect of carriers.

3. To support ground maneuver elements without moving the aircraft nearer to the enemy

Enemy troops can walk to an air base, but they can't swim to an aircraft carrier unless it's anchored. Attacking a carrier battle group in small boats is not a realistic option. You need your own blue water naval assets if you wish to engage prudently operated aircraft carriers, which use hit-and-run strikes and movement to confound attempts to sink the carrier. This fixes the "minimum complexity solution" that any potential adversary can effectively employ to neutralize Canadian air power, and that bar is set fairly high. In the real world, there's never been an effective submarine attack against a carrier. These fictional "carrier sinking scenarios" always begin with conveniently co-locating the submarine and aircraft carrier. If the submarine had to move underwater at 20 knots to at least keep pace with a carrier, then it's going to make enough noise to be detectable. After the ASW helos fix its location, it's probably not going to survive. There's far more mythology to submarine capabilities than real world equivalence. However, when operated at low speeds, they make fantastic stealthy first-strike platforms that can do a lot of damage in a hurry. The majority of ships sunk or seriously damaged since WWII received bomb or missile hits or they struck a mine. If I had a sizeable fleet of attack submarines, I would use them as the excellent first-strike weapons that they are (against commercial ships or land targets that can't fight back), and only reluctantly attempt to engage carriers with them if no better options were available. I'd much rather lose an entire squadron of heavy fighters and expend several hundred cruise missiles to successfully attack a carrier, than lose an attack sub in an ill-advised attack wherein multiple ships have the opportunity to sink my sub.

4. To rapidly distribute supplies to friendly forces or humanitarian aid after a natural disaster

The ability of carriers to deliver badly needed consumables, or to medevac any injured or wounded, in a timely manner, is very under-appreciated. Smaller ships can and will do this to a limited degree, but a purpose-built ship has capacity that destroyers lack. If there's a mud slide or fire or earth quake that destroys a town, a nearby carrier is like "manna from heaven". Even the smallest carriers have cavernous hangar bays that can be packed to the gills with food and water, or a makeshift trauma triage center set up in the hangar bay to treat the wounded. Purpose-built ships are even better, but spendy, and you don't get to use them very often.

5. To provide a top-notch air crew training program that creates aviators with superb basic airmanship skills, useful for saving stricken airliners

Flying from aircraft carriers forces air crews to become better aviators because maneuvers must be more precise, greater attention to detail is exercised when it comes to the aircraft's "health" is required (there's very little of the usual "we'll try flying this marginally mission capable plane, just for the hours"), weather briefs are considered a critical integral element of every flight brief rather than a check in the block, great effort is spent detailing alternative ingress and egress routes to get yourself out of trouble (from bad weather and enemy action), and an absolute mastery of emergency procedures is necessary, so that the response to a safety-of-flight incident is instant and decisive. Most fast jet pilots are pretty decisive in the cockpit, but naval aviation takes it to another level. You cannot be complacent or indecisive or gloss over details while operating jet aircraft from a ship, or people will die. I don't doubt that there are more than a few Air Force and Army aviators who are every bit as well-trained and detail-oriented, but all of them said they learned something on exchange tours to become carrier qualified.

Online

Like button can go here

#2812 2025-03-15 05:23:07

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 8,449

Re: Politics

RobertDyck,

kbd512, you have argued for American supercarriers because you're familiar with them.

I advocated for them on the basis of the capabilities they provide (a true "air force in a box"), and the simple fact that the Forrestals were not terribly expensive ships to purchase and operate. They were less than half as expensive as the Enterprise or Nimitz classes in terms of inflation-adjusted dollars. They would've been even less expensive without the 8 sponson-mounted 5-inch guns that caused so many design issues. Modern power and propulsion options (SCO2 or SOFCs) would make Forrestals drastically less expensive to operate, because fuel burn rates would be on-par with LM2500-powered destroyers. The cost to construct modern warships is not a function of their displacement or physical dimensions. A 25,300t LPD-17 class ship costs less to construct than a 9,900t Flight III Arleigh Burke class destroyer, in terms of inflation-adjusted dollars. The cost difference is explained by all the expensive weaponry and sensors that the Arleigh Burke carries. The equipment cost of a warship frequently exceededs its hull construction cost.

However, I understand the argument that Canada will typically operate fighters from land bases. It has good points in its favor, but the probability of it surviving a sneak attack is low unless that assets are spread between multiple air bases, in which case there's not much available air power at any given location. Still, if this is how Canada wishes to operate its national defense, then I think it will work well enough, at least until the shooting starts, and then serious air defense missile batteries are required to keep an air base intact.

After checking the physical dimensions of the dry dock in your largest ship yard, I have now come to the same conclusion that an indigenous super carrier is out of the question for Canada. However, a ship the size of USS Makin Island (LHD-8) could be built there. Makin Island is 257m long, has a beam of 31.8m, draft is 8.1m, and at around 40,150t full load displacement, it fits the description of a large modern "light carrier".

USS Makin Island equipped with extra F-35Bs:

Online

Like button can go here

#2813 2025-03-15 12:08:39

- RobertDyck

- Moderator

- From: Winnipeg, Canada

- Registered: 2002-08-20

- Posts: 8,362

- Website

Re: Politics

CBC today: Canada reconsidering F-35 purchase amid tensions with Washington, says minister

In TV news by the same channel, they said Canada has already paid for purchase of 16 F-35 aircraft. A total of 88 aircraft were ordered, but the Minister is now considering cancelling anything after the ones already paid for. They are considering their other options.

SAAB in Sweden bid on the contract to provide FAC-39 Gripen aircraft, and offered to perform the bulk of the manufacturing in Canada. Dessault in France bid to provide Rafale aircraft, and also offered to perform the bulk of the manufacturing in Canada. In both cases, just aircraft for Canada. The other aircraft considered was the Eurofighter Typhoon, but that manufacturer did not offer to manufacture in Canada. Cost per aircraft of Gripen and Rafale are almost identical to F-35. Sweden and France are both NATO allies. Eurofighter Typhoon is manufactured in UK, Germany, Spain, and Italy. France was involved with Eurofighter in its early development, but decided to part ways and build their own Rafale instead. All these are NATO countries. However, the Eurofighter consortium wouldn't build in Canada so wasn't preferred.

Offline

Like button can go here

#2814 2025-03-15 13:02:59

- RobertDyck

- Moderator

- From: Winnipeg, Canada

- Registered: 2002-08-20

- Posts: 8,362

- Website

Re: Politics

Ok, let's do aircraft carriers. Canadan CVN that I came up with. Decks below flight deck but above water line do not extend as low as a Nimitz. Because they must be above ice when icebreaking. Gallery deck is built as a truss to support flight deck. However, a chunk of the gallery deck above the upper aft hanger is absent, making the ceiling of that part of the hanger the underside of the fight deck. This provides additional ceiling high for repair operations of helicopter rotors. Aircraft parking on either side of runway. Port side parking slightly wider to allow SuperHornets to park perpendicular to runway. Hangers design to allow all aircraft except Dash-8 cargo aircraft to park in hangers. This allows the entire flight deck to be vacant in case of a severe arctic storm. Upper aft hanger deck used for maintenance, but when used for parking the aircraft can be changed: 6 S-3B Viking, or 8 Dessault Rafale, or 6 SuperHornet, 8 F-35B.

Hanger decks (shown with F-35C)

Flight deck configurations (top image shown with CF-18 Hornets)

Cross section (does Canada need a flag bridge?)

Offline

Like button can go here

#2815 2025-03-22 19:33:18

- RobertDyck

- Moderator

- From: Winnipeg, Canada

- Registered: 2002-08-20

- Posts: 8,362

- Website

Re: Politics

A Canadian actress working in Mexico tried to return to the US. She had a work visa for the US, she entered at a normal border crossing and presented her work visa. However, the arrested her anyway. She was accused of attempting to illegally enter the US. She did no such thing, she had a work visa. However, some bureaucrat revoked her work visa, and didn't bother to tell her. If that happened, the should have denied her entry to the US. But they didn't do that either, they arrested her. They accused her of being in the US illegally. She wasn't, in fact they arrested her at a border crossing so she wasn't in the US at all.

This tells me visitors from Canada are not safe. The US has announced they will arrest tourists. The Canadian actress was white, so this wasn't a race thing. I have a valid Canadian passport, attended last year's Mars Society Convention in Arizona. This year the Convention is in Los Angeles. I've never been to California at all. I worked in a suburb of Richmond Virginia for 6 months in 1996. I worked in Miami Florida for 9.5 months, stayed to the end of the month so lived there 10 months in 1999/2000. I've visited many places in the US, but never been to California before. However, due to Trump's aggressive actions my girlfriend is telling me I shouldn't attend the Mars Society Convention this year.

Offline

Like button can go here

#2816 2025-03-22 20:16:44

- RobertDyck

- Moderator

- From: Winnipeg, Canada

- Registered: 2002-08-20

- Posts: 8,362

- Website

Re: Politics

Offline

Like button can go here

#2817 2025-03-22 20:35:29

- Void

- Member

- Registered: 2011-12-29

- Posts: 9,201

Re: Politics

Worlds in collision. Collateral damage. It is not personal, and it is not within the powers of people like us to control. But maybe more work is needed to handle exceptions. America has to examine its other side, and that leads to friction with the British and French, who are asymmetrical in profile, which conflicts with our full spectrum nature. I may or may not want to elaborate. But in this era, Russia becomes a natural not quite partner, at a distance.

Canada is of course more or less still ruled by the British and French, so there is an incompatibility that has built up. The main thing is to avoid a slaughterhouse, which our guy is trying to do.

Ending Pending ![]()

Last edited by Void (2025-03-22 20:40:35)

Is it possible that the root of political science claims is to produce white collar jobs for people who paid for an education and do not want a real job?

Offline

Like button can go here

#2818 2025-03-22 21:23:49

- RobertDyck

- Moderator

- From: Winnipeg, Canada

- Registered: 2002-08-20

- Posts: 8,362

- Website

Re: Politics

Russia's not a natural anything. It's a dictatorship. I had hoped to establish normal relations with Russia. Under Boris Yeltsin, Russia behaved mostly like a modern mature society. They had massive corruption to deal with. At least Russia didn't invade, conquer, subjugate its neighbours. Now it is. Russia is colonizing a white country, treating the inhabitants as slaves to be exterminated. Russia does not believe in democracy, does not believe in a republic. Russia is a dictatorship.

The United States and Canada were founded by the same parent countries from Europe. We are mostly British with some French. New Orleans still speaks French. France supported the American war of independence, provided weapons and even uniforms. The south of the US was settled by Spain. Canada didn't have much influence from Spain, but there was some contact. German settlers were part of both countries. Russia never was part of either country.

Offline

Like button can go here

#2819 2025-03-23 09:48:41

- Void

- Member

- Registered: 2011-12-29

- Posts: 9,201

Re: Politics

Quote:

Russia's not a natural anything. It's a dictatorship.

Well, it is a cultural heritage and has its own specific genetics as well.

As far as dictatorship, it is not that much different than the pretend representative governments in Latin America, that we tolerate. A thing that appears to be actual, is that as we encourage the Latin Americans to try and try again, they do seem to be catching on more and more.

And by the way, we now see some faltering in the Western Europeans. Canada being in part an extension of Western Europe, obviously we need to stay awake about it. Western Europe, did two Napoleons and a Hitler.

The cities of club med are natural harlots, it is difficult to keep them on a moral pathway.

Dublin<>London<>Paris<>Rome<>Athens<>Cairo>>>

They are in the line of the ancient Farmers, but not purely so. The Russians may be like the Finns, a more direct descendent of the Yamnaya. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yamnaya_culture

Quote:

The United States and Canada were founded by the same parent countries from Europe. We are mostly British with some French. New Orleans still speaks French. France supported the American war of independence, provided weapons and even uniforms. The south of the US was settled by Spain. Canada didn't have much influence from Spain, but there was some contact. German settlers were part of both countries. Russia never was part of either country.

We bought Alaska from the Russians, granted ethnically their touch on North America has been light. Yamnaya, have been adjacent to Siberian peoples. And the so you call "First Nations", were quite dominant in the now called America, although there may be some South pacific resemblance in Brazil.

I assign the color Orange to Russians, and Siberians. This is not about skin color. Think color wheel. I assign green to the Latins. Red to China, Yellow to the Germanic, Blue to the Sub-Saharans, and Purple for the Middle East.

The idiotic attempt by the convergence of American Greens and European Greens to shatter the Orange, was contrary to American needs. If Russian were shattered, then it is likely that China would fill the vacuum, and so would be in the Arctic. Then we would have to deal with that.

The Russians helped us to fend off the British and French during the Civil War, and were valuable in the world wars, to American interests.

If I were to possess Russia, by some strange imagining, I would want to invent Russians, and place them in Russia, as, they are a convenience to North America. It is nonsense for America to want to possess Russia. Our efforts will earn gain more in North America.

Last edited by Void (2025-03-23 10:02:45)

Is it possible that the root of political science claims is to produce white collar jobs for people who paid for an education and do not want a real job?

Offline

Like button can go here

#2820 2025-03-23 10:01:08

- RobertDyck

- Moderator

- From: Winnipeg, Canada

- Registered: 2002-08-20

- Posts: 8,362

- Website

Re: Politics

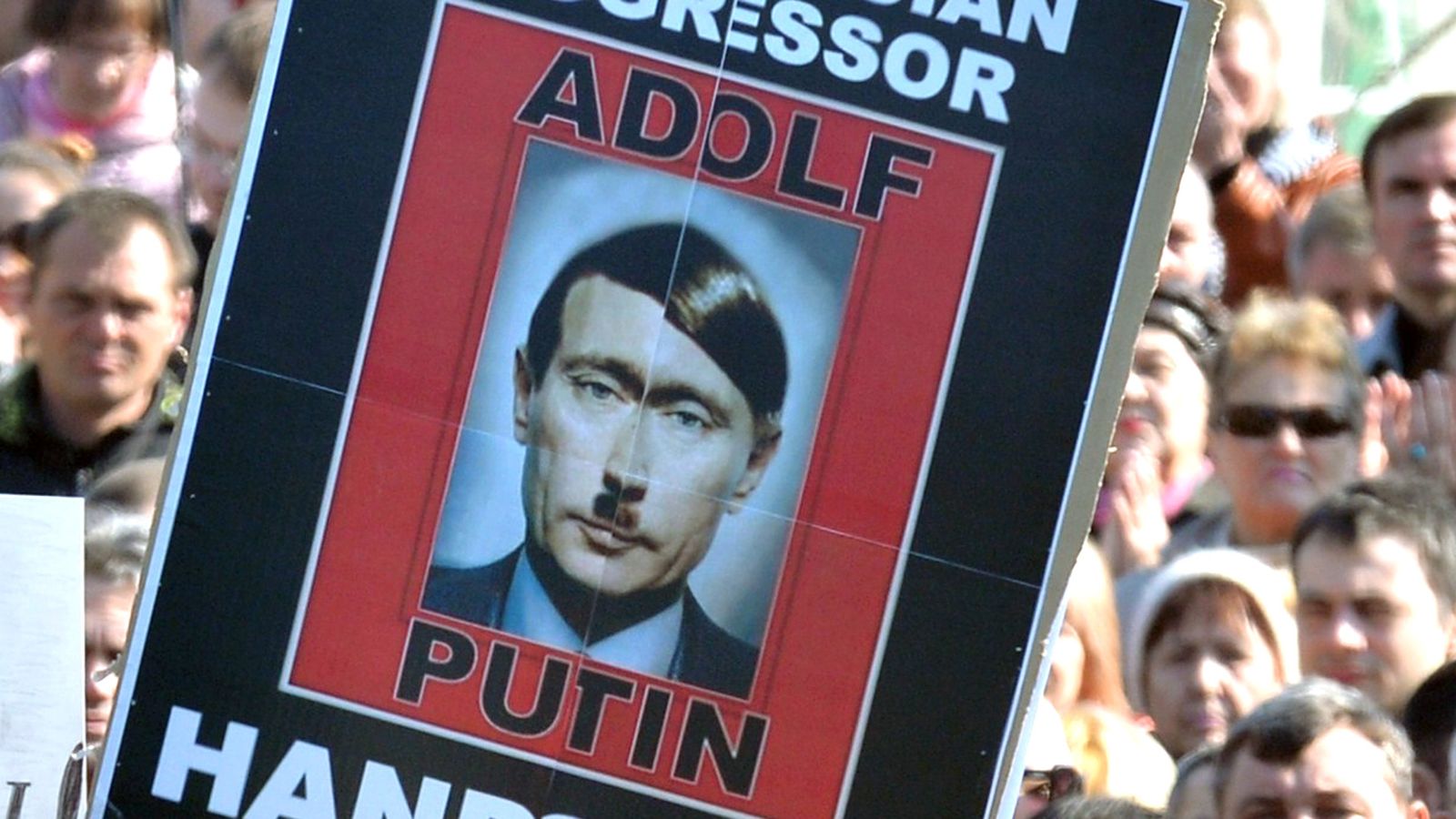

WTF?!? What are you talking about? Have you really fallen this far into the propaganda of Putin? Democracy started in Greece, part of Europe. The United States was founded on principles of freedom. WTF are you doing? Has your account been hacked by a Russian? Is this really Void? The Declaration of Independence, second sentence: "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness." The Constitution of the United States starts: "We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America." So WTF are you doing supporting a dictator? Adolf Putin is a dictator. Russia is not allowed to protest. Russian media does not allow anything other than official government policies. The average income of a working person in Russia is US$14,771 per year!!!

Offline

Like button can go here

#2821 2025-03-23 10:08:53

- Void

- Member

- Registered: 2011-12-29

- Posts: 9,201

Re: Politics

You should have allowed me to do more.

Actually, Iceland has been a republic for 1000 years, except for a 50 year occupation by Norway.

Democracy is bad. We say democracy as it is easier to say than representative republic. Of course you are not a representative republic.

I believe that a Scottish person said that "Democracy is where you can vote yourself a paycheck". More or less. It lends itself to a patronage system, which is what the Democrats were trying to set up.

Is Russia a "Real Boy" at this time? Not so much, but they are also under deep stress. We made it more possible for strong man dominance in Russia. But we should be blessing Putin. He is keeping the real daemons from getting power. Him, we can deal with. Of course they have expectations of our stupidity, as it has been very evident.

I could pick apart the logical story about what has happened, but you are not in the mode of logic just now, maybe we should just discontinue this dialog.

Ending Pending ![]()

https://www.rbth.com/politics_and_socie … war_823252

I believe that this age resembles that age.

At that time the British were strong in Canada, and Napoleon the III was in Mexico. Obviously, the European powers were thinking about taking down the American Republic and they were also looking nasty at the Russians. The deal was that Russia did not want its fleet bottled up in its ports, and the USA needed the Russian navy to discourage a full on assault from Europe.

The European Union is not that dangerous at this time, but we know how quickly the NAZI threat appeared from ashes of history. It is not wise for us to trust that it could not happen again, the Western Europeans have been backsliding on so called "Democracy".

It does not look trustworthy.

Ending Pending ![]()

Last edited by Void (2025-03-23 10:17:04)

Is it possible that the root of political science claims is to produce white collar jobs for people who paid for an education and do not want a real job?

Offline

Like button can go here

#2822 2025-03-23 10:21:59

- RobertDyck

- Moderator

- From: Winnipeg, Canada

- Registered: 2002-08-20

- Posts: 8,362

- Website

Re: Politics

The Russians helped us to fend off the British and French during the Civil War, and were valuable in the world wars, to American interests.

Now that's fiction. Russia didn't do squat!!! And the French did NOT get involved in the Civil War. In fact, France maintained an official policy of neutrality during the Civil War.

Reference: France and the American Civil War

Britain also remained neutral. Where do you get this fiction that America had to fight them?

Reference: United Kingdom and the American Civil War

As for World War 2, realize Russia was allied with the Nazis at the beginning of the war. Russia made a deal with Nazi Germany to invade Poland. Russia attempted to invade Poland on its own in 1919/'20 but failed. In 1939, the deal was Nazi Germany invaded from the west, Russia invaded from the east 3 days later. Russia tried to claim they were there to "liberate" Poland from the Nazis, but reality is they made a deal to invade together and divide it up. After that, Russia attempted to invade Finland but failed. When Adolf Hitler saw Russia couldn't even defeat Finland on their own, he thought Russia was weak, so invaded Russia. That's why Russia hates the Nazis so much; they were an ally that turned on them. Stalin sought help from the Allies after Nazi Germany invaded Russia. Russia fought the Nazis in the east, on Russian soil and the soil of eastern European countries that Russia had conquered/subjugated/annexed.

Offline

Like button can go here

#2823 2025-03-23 11:44:25

- Void

- Member

- Registered: 2011-12-29

- Posts: 9,201

Re: Politics

Had the confederates won the Civil War, the British in the north could easily have dominated the remnant of the USA. I expect that both the British and French were teetering on a decision, and the Russian navy helped encourage them to stay more neutral.

Lincon was protecting the republic from European Colonialism. That was the real war.

Neither the British nor the French were to be held in contempt.

They were both very powerful.

Had France succeeded in Mexico, then the Confederates intended to conquer Latin America, as they all felt that they could then have slaves. So, the remnant of the American Republic would have been pinned between the British Empire, Frances Mexican Empire, and an expanding Confederate Slave Empire.

When Lincon said he that his priority was to save the republic, that was practical, because if the republic fell, there would be no reason for either the British, French, or Confederates, to have held representative government in respect. My bet is that at that point the three powers would have conquered the remnant American republic.

The Soviet Union in WWII is not the same as Russia now.

Both Hitler and Stalin were products of the very old world intruding into the newer world of Europe. Neither of them came from the North Sea coast.

The communists believed that the Fascist would in the end convert to Communism.

The war between the Dominant Man and the Capable Man. America Capable, NAZI, Soviet, Dominant method. But in our cultural fiction, the North Sea peoples are demonized.

So, I do see the value of working with Russia. But I would count my fingers, from time to time.

Ending Pending ![]()

Last edited by Void (2025-03-23 11:56:03)

Is it possible that the root of political science claims is to produce white collar jobs for people who paid for an education and do not want a real job?

Offline

Like button can go here

#2824 2025-03-23 12:54:42

- RobertDyck

- Moderator

- From: Winnipeg, Canada

- Registered: 2002-08-20

- Posts: 8,362

- Website

Re: Politics

Had the confederates won the Civil War, the British in the north could easily have dominated the remnant of the USA. I expect that both the British and French were teetering on a decision, and the Russian navy helped encourage them to stay more neutral.

Lincon was protecting the republic from European Colonialism. That was the real war.

That is one steaming pile of bullshit. Where did you get that? There's no way the British would invade. The US defeated the British in the War of Independence, and the US would remain free no matter what.

The South ruled the US until Lincoln became President. Lincoln wasn't the first President from the North, but it was the first time that Congress was dominated by the North. The South dominated Congress from the signing of the Constitution until the election that Lincoln won. The Civil War wasn't about slavery; that's propaganda that the North started while the war was still ongoing. When I lived in a suburb of Richmond Virginia, I got a long lecture from a couple who were locals. I checked what they told me with university level history textbooks, and they were right. As President, Lincoln signed a law allowing slavery to continue to exist. The law said any Northern states that didn't want slavery, would be slavery free. Southern states that wanted slavery, could continue. Any new states would be slavery free, so slavery would not expand. Most importantly, if a slave in the South escaped to the North, even though he was in a Northern state without slavery, he would be captured and returned to his "owner" in the South. The war was really about power and money. Every war is always about power and money. If someone tried to convince you otherwise, you've been lied to.

As soon as the North dominated Congress, they passed new taxes only on products produced in the South. This was to establish economic dominance as well as political. Once that was established, the North would retain control over Congress. Before this, the South was rich and in control. So again, money and power. But no matter what, neither Britain nor France was going to take over.

Offline

Like button can go here

#2825 2025-03-23 18:02:14

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 8,449

Re: Politics

RobertDyck,

Do you actually believe anyone in America, regardless of where their politics fall, unless they are former Russian nationals themselves, cares about what that little commie bastard wants?

In another 10 years, Putin will be gone, one way or another. Russia and the Russian people will still be there. Russia, the nation, whomever it is led by, is what the Europeans and the rest of the world have to deal with. Here in America, we are presently trying, key word here, to take a modestly less antagonistic approach towards Russia, because we're going to need them to at least sit out the coming war with China. Right now we Americans have bigger fish to fry. We have real commies to deal with in China, they are on the war path by President Xi's own statement, and they do in fact appear to be preparing for war in a serious way. The Chinese are not wannabe commies. They're about as real and serious as a heart attack. You should wake up and take notice. Europe is not the world. It's important to us, but Europe is not the end-all / be-all. America doesn't fixate on any particular part of the world, because we cannot afford to do that.

Whatever damage you think Russia has done or will do to nations in Europe, multiply that somewhere between 10 and 100, because that's what China can feasibly do. Right now, they're gearing up to engage half the nations in Asia, which is where all of our advanced tech comes from, a healthy chunk of the global energy supply transits through, lots and lots of motor vehicles, foodstuffs, textiles, and the list goes on. China is not a joke. China's economy is not the size of Italy, unlike Russia. They can do real damage, not merely to one nation or region, but to the entire world. COVID was a preview of things to come.

Online

Like button can go here