New Mars Forums

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

Announcement

#1 2025-01-22 11:22:22

- PhotonBytes

- Member

- From: AUSTRALIA

- Registered: 2019-12-28

- Posts: 116

- Website

55km Mars tunnel idea 2.0

Main Article:

https://photonbytes.com/2025/01/23/55km … -idea-2-0/

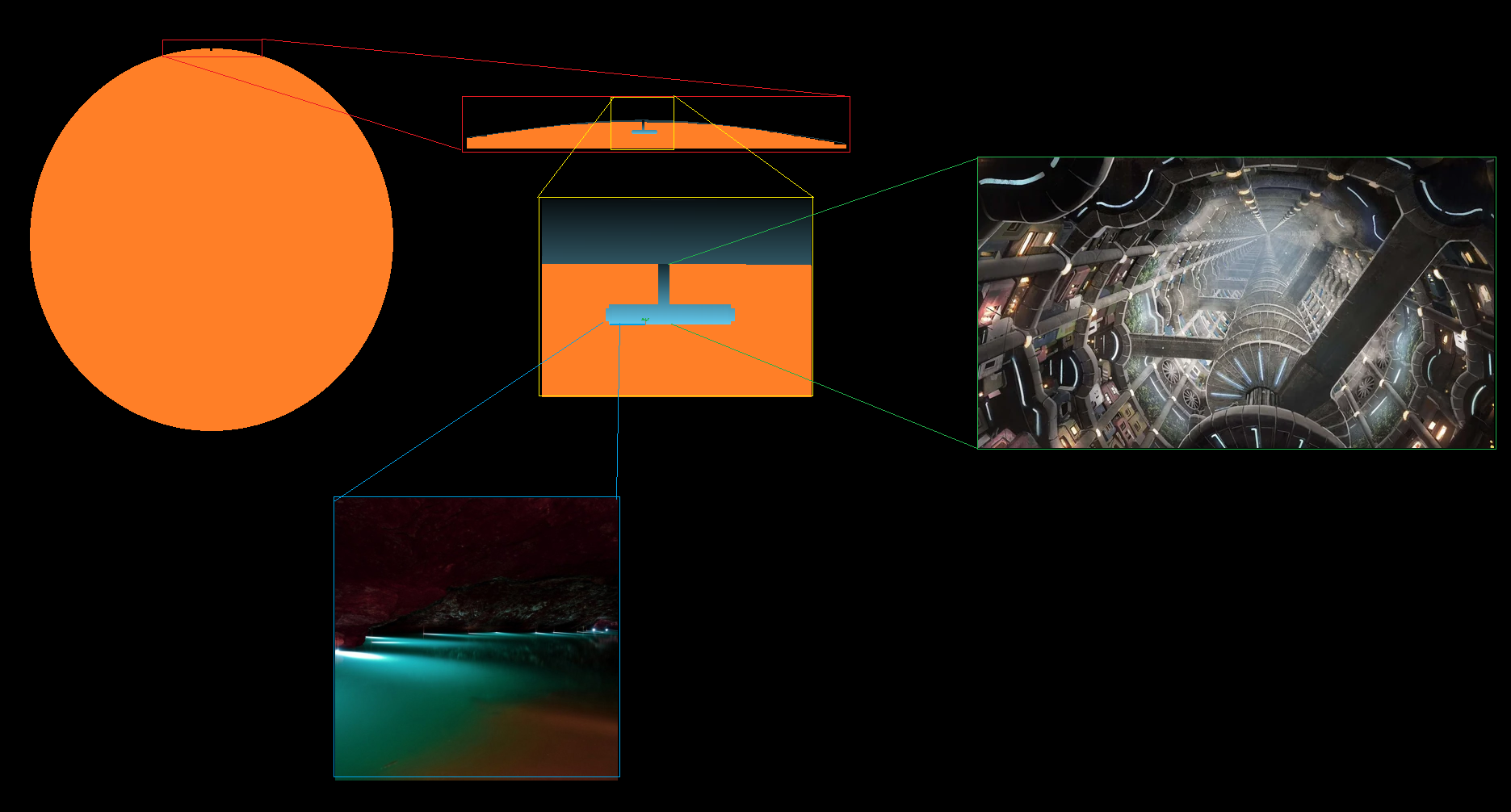

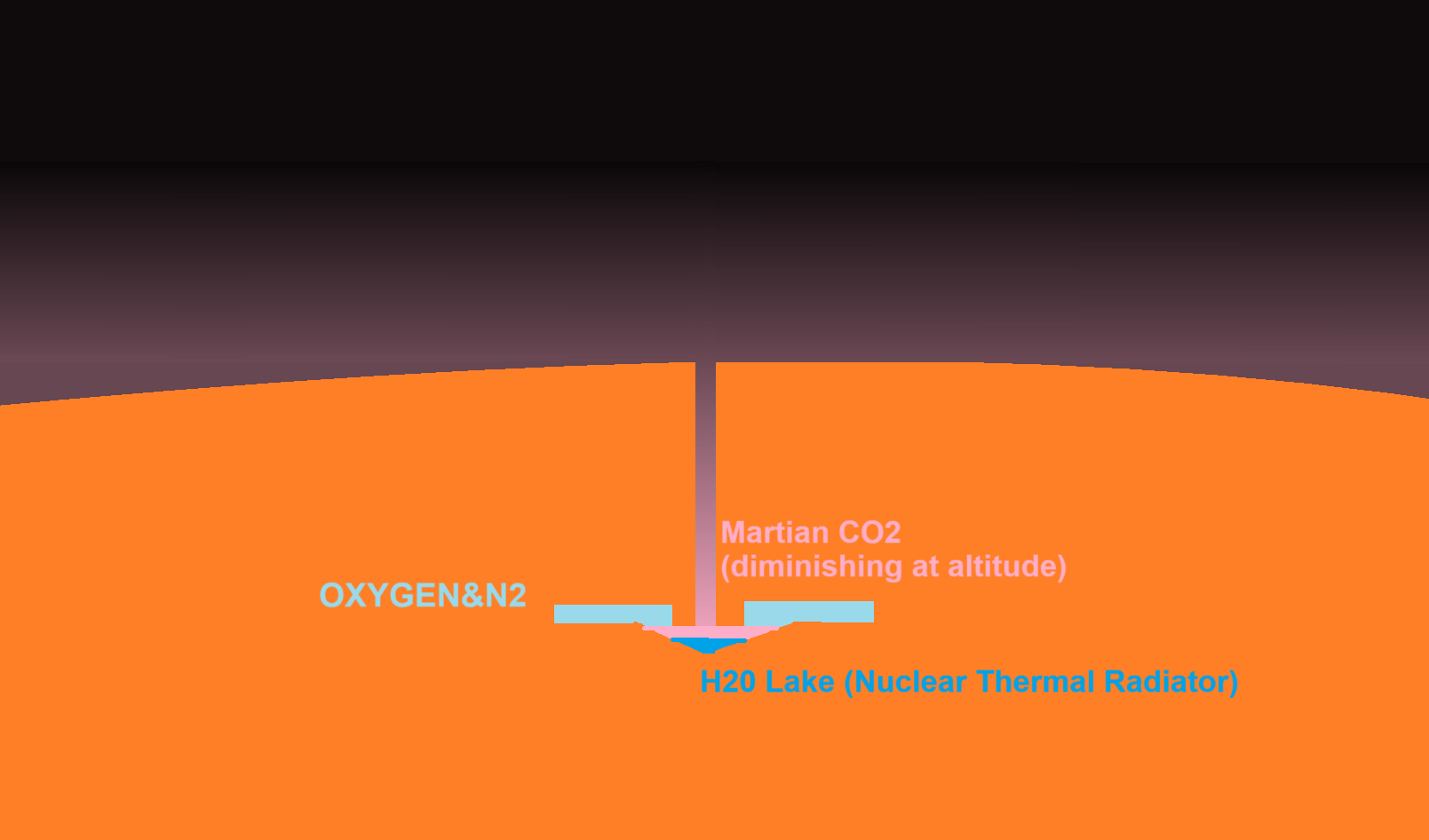

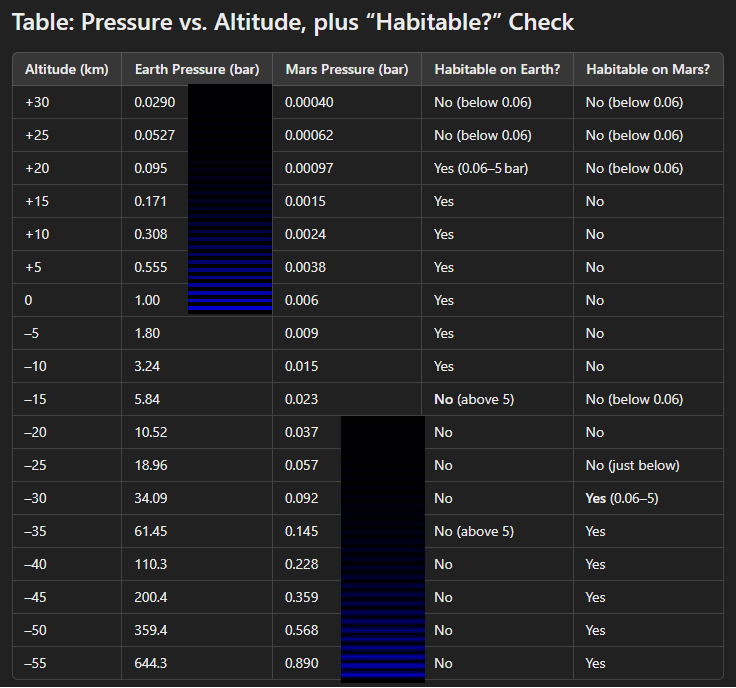

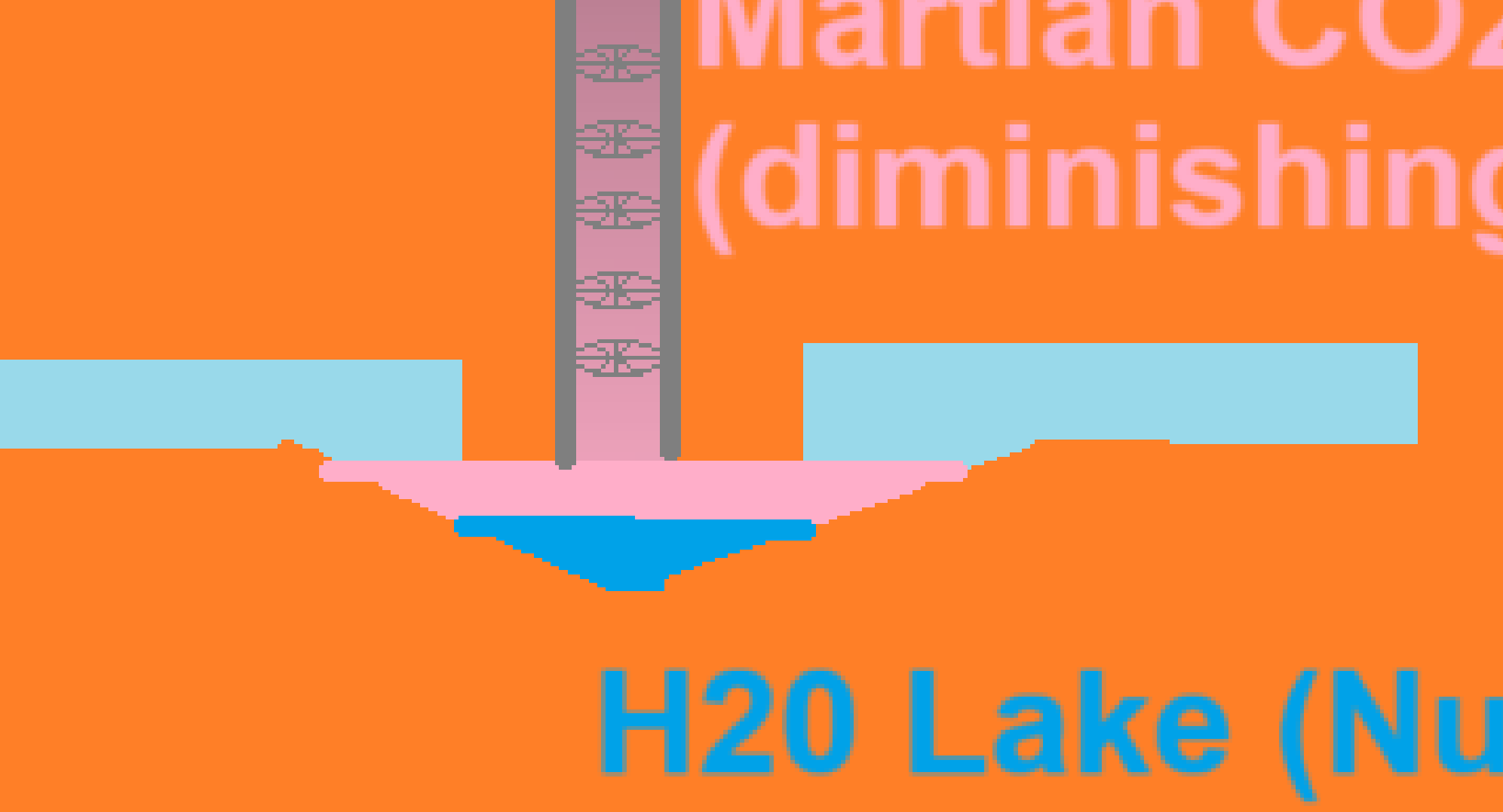

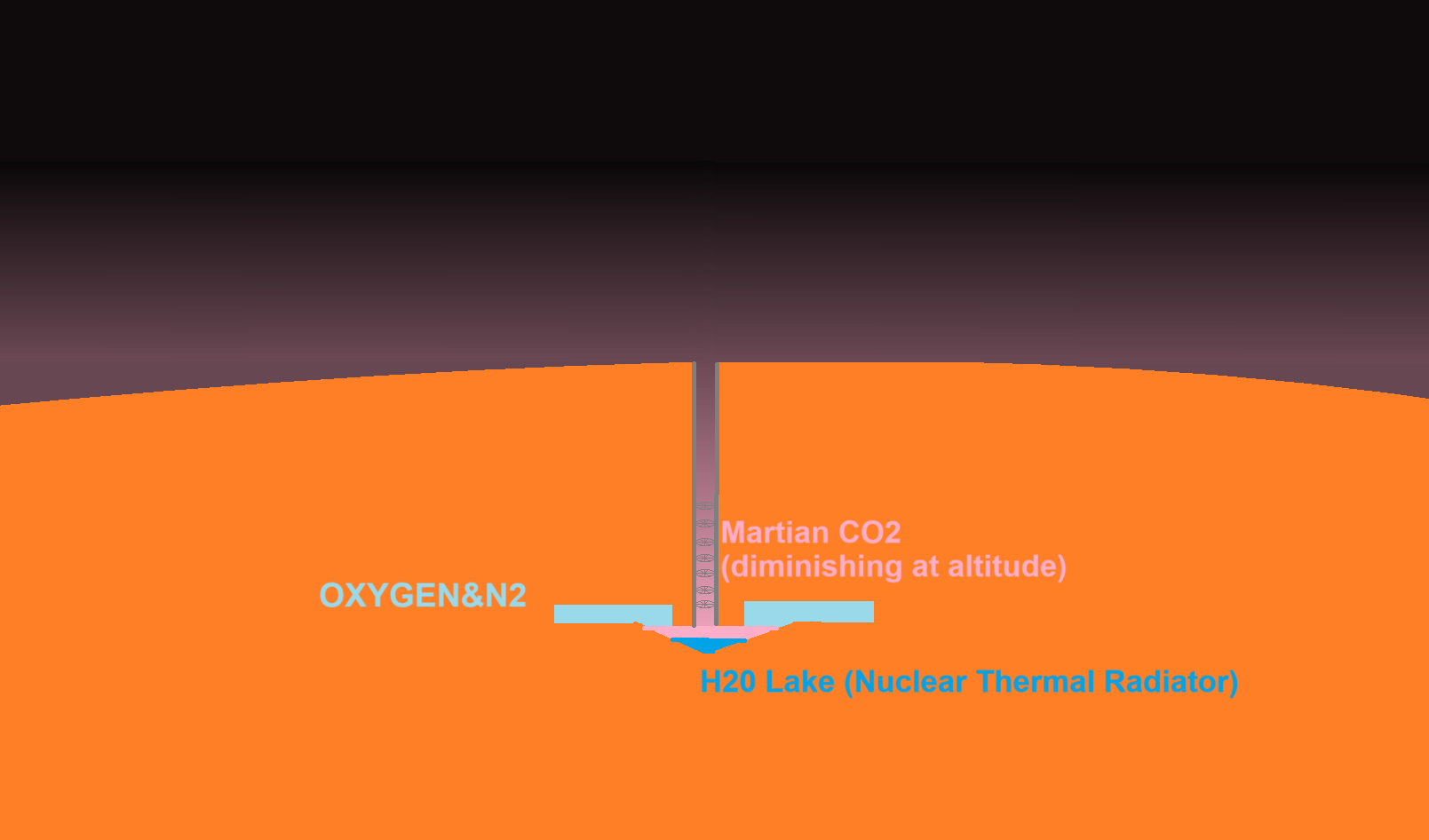

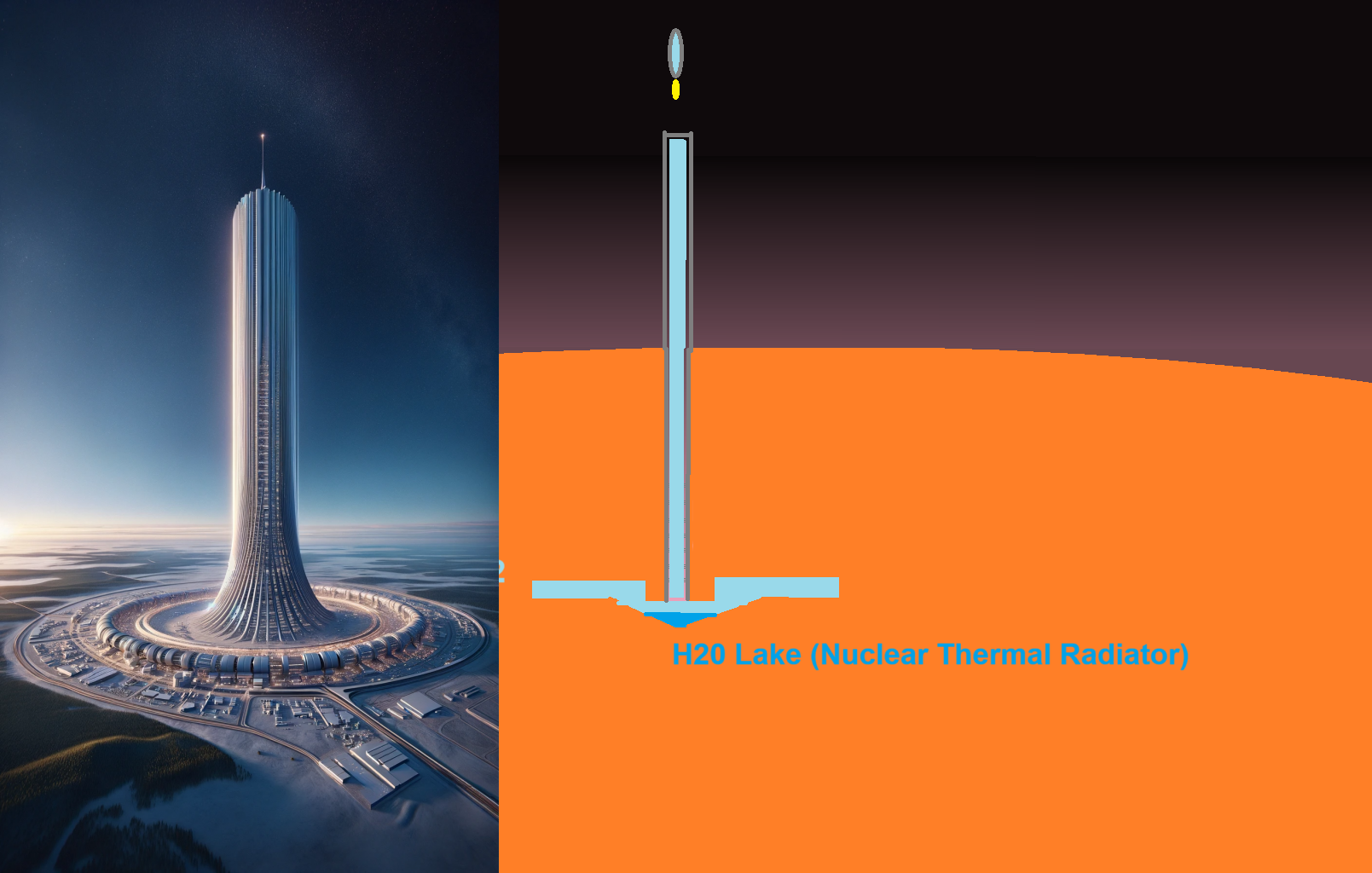

Considering the scale height of Mars, a 55km deep tunnel on Mars with a “silo” built into the vertical shaft can allow humans to live in Mars in the lower end of the tunnel where there is 1 bar of atmospheric preassure, there and any cavity excavated out horizontally after that. The silo could be a nuclear thermal powered structure with a built in drill bit. We can have artificial lighting powered by a nuclear thermal reactor and waste heat from it could keep the air warm by heating artificial lakes.

Inspiration of the megastructure from the TV series SILO:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JlWCIY6gNIw

Last edited by PhotonBytes (2025-02-02 17:14:55)

I play the piano

https://fb.watch/s7XPqxw02-/

Offline

Like button can go here

#2 2025-01-23 09:45:39

- Void

- Member

- Registered: 2011-12-29

- Posts: 9,350

Re: 55km Mars tunnel idea 2.0

PhotonBytes,

It has gradually occurred to me that Mars/Phobos/Deimos can be a world for things that fly. An ~.38 g world. Optimists think that the bulk Mars atmosphere can become as much as 2.5 times as thick as it is now, from unthawed CO2 ice.

This would make the radiation situation on Mars much better than it is now.

Hellas, at its deepest point might be an air pressure of about 11.5 mbar. 2.5 times that would be perhaps 28.5 mbar, but the pressure would be more than that, as compression would make the lower layers of atmosphere denser and denser.

https://endmemo.com/chem/vaporpressurewater.php

That would allow a vapor pressure of 23.3 degrees C or more in that lowest spot on Mars.

Granted, for open water evaporation would be severely troublesome. But I think that covered lakes/canals, might work OK. Many Locations on Mars have a pressure of 9 mbar. 2.5 times that would be 22.5 or more, due to compression of layers. So, in those locations a vapor pressure of 19.5 or more.

A method to heat that CO2 up is provided here: https://news.uchicago.edu/story/scienti … -warm-mars Quote:

UChicago, Northwestern study suggests new approach to warm Mars could be 5,000 times more efficient than previous proposals

So, if Mars could be altered in that way, radiation would be better protected from on the surface, and the operation of ships like Starship might be better facilitated. The terminal velocity coming down would be improved, and the friction going up would not be that much increased, I think. So Starship SSTO would be a thing I think, providing for materials interchanges with Phobos and Deimos. And beyond that would be the asteroid belt.

So, I do not think that the best use of Mars is to become "MoleMen". But even so, your ideas in some ways could be worth chasing down. Especially with robotics being a very likely field of expansion of capabilities.

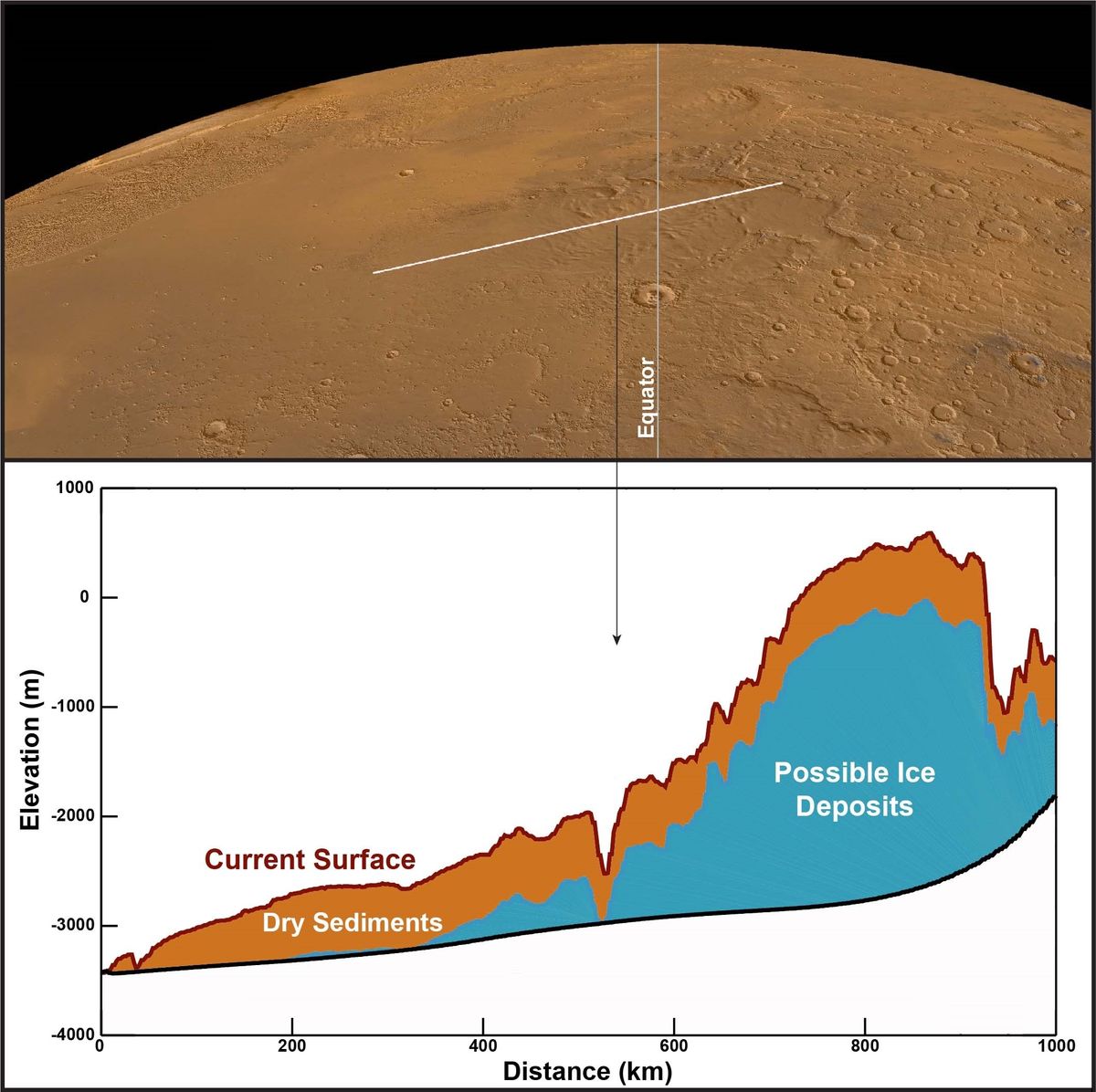

Near the equator, this apparently exists: https://www.space.com/mars-water-ice-eq … ozen-ocean

Image Quote:

Quote:

In this image, the white line on Mars' surface (top) shows a stretch of land that was scanned by MARSIS. The graph below shows the shape of the land and the structure of the subsurface, with the layer of dry sediments (likely dust or volcanic ash) in brown and the layer of suspected ice-rich deposits in blue. The graph shows that the ice deposit is thousands of meters high and hundreds of kilometers wide. (Image credit: CReSIS/KU/Smithsonian Institution)

If the sediments over the ice are cemented reasonably well then you could dig a shaft and tunnel network in that, reaching into the ice body.

Underground cities in Anatolia: https://www.bing.com/images/search?q=un … RE&first=1

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Derinkuyu … round_city

So, deep volcanic ash sediments could allow relatively easy digging into to make an underground city.

The ice may be relatively easy to dig into as well.

Suppose you dug a city, and put artificial lakes above it with domes.

You could dig diagonal shafts from the city down into the ice. Diagonal, so that you don't undermine the city.

You might start like this:

By digging diagonal in the ice you can get makeup water, but not undermine your city in the volcanic sediments.

Then if you have some reason do dig deeper, maybe drill for geothermal you could do that below the ice layer.

And as this is to be near the Equator, then an orbital space community could be linked to this city, and they may trade resources.

Anyway, if you are going to dig then you have to start somewhere. This place could provide both volcanic sediments and massive amounts of ice.

Ending Pending ![]()

This would fit in with an "Avian" Mars, and be supportive of an expansion to the moons of Mars and the asteroid belt.

Ending Pending ![]()

Last edited by Void (2025-01-23 10:49:53)

Is it possible that the root of political science claims is to produce white collar jobs for people who paid for an education and do not want a real job?

Offline

Like button can go here

#3 2025-01-23 10:36:57

- Calliban

- Member

- From: Northern England, UK

- Registered: 2019-08-18

- Posts: 4,305

Re: 55km Mars tunnel idea 2.0

The compressive pressure exerted by overbearing rocks at that depth would be approx 600MPa. The same as a 20km depth on Earth. It would be very difficult to prevent the tunnel from collapsing inward. Instead of relying on the pressure gradient of the natural atmosphere, you could instead build the habitat under a much shallower layer of rock. A 10m thickness of basalt on Mars is roughly equivelant to a 1 bar pressure. So your tunnel doesn't have to be very deep. It just cannot be open to the atmosphere.

"Plan and prepare for every possibility, and you will never act. It is nobler to have courage as we stumble into half the things we fear than to analyse every possible obstacle and begin nothing. Great things are achieved by embracing great dangers."

Offline

Like button can go here

#4 2025-01-23 13:19:28

- PhotonBytes

- Member

- From: AUSTRALIA

- Registered: 2019-12-28

- Posts: 116

- Website

Re: 55km Mars tunnel idea 2.0

UPDATE 2.0: Chat GBT corrected it self youre right it's going to be 576MPa according to my 2nd conversation with AI, and Martian Basalt compressive tolerance ranges from 100-200MPa. Martian regolith based conconcrete only has 72MPa compressive strength so need to extract the iron out of regolith to make high strength steel that is 700MPa for the bottom section of the tunnel. I am designing a steel silo made of this material that is a cylinder but thickness yet to be determined, with horizontal cross beams rotating along the height of the tunnel like stairs/helix also made of high strength steel to support the sides evenly. The design now looks just like the TV series silo with the helix stairways! Coincidence?

UPDATE: Chat GBT thinks it will be 326MPa not 600MPa. So its about 3 X the preassure Challenger Deep delt with in the deepest Ocean point on Earth (Mariana Trench) that is 110MPa. Did you factor in Martian gravity?

ORIGINAL REPLY:

Don't forget Mars has less gravity. Have you factored in Martian gravity when calculating the compressive pressure? Regardless remember we are talking about building a silo which replaces the excavated dirt and it will act to prevent the colapse with horizontal stabalization. The design of the Silo is something that needs to be discussed. So far this is just the basic idea.

On Earth we have reached 12km with a small narrow hole so if you're right it's just a matter of doubling the results in Kolar Peninsula and scaling up the diameter. I am thinking a nuclear powered massive drill bit built into the silo that can be lowered and raised electrically and have huge RPM from the nuclear reactor.

We could also consider preassurizing the tunnel with 1 bar or above to compensate for the 600MPa you quoted. Thanks for this work by the way forces me to consider this variable! 600MPa is 6,000 bars. So if we preassurize it with gas from Martian atmosphere/ice it would not be habitable while we drill until some solid re-enforcements are built around the circumference with a good pylon design.

Welcome any suggestions for the silo design! Im not a structural engineer!

The compressive pressure exerted by overbearing rocks at that depth would be approx 600MPa. The same as a 20km depth on Earth. It would be very difficult to prevent the tunnel from collapsing inward. Instead of relying on the pressure gradient of the natural atmosphere, you could instead build the habitat under a much shallower layer of rock. A 10m thickness of basalt on Mars is roughly equivelant to a 1 bar pressure. So your tunnel doesn't have to be very deep. It just cannot be open to the atmosphere.

Last edited by PhotonBytes (2025-01-24 00:49:08)

I play the piano

https://fb.watch/s7XPqxw02-/

Offline

Like button can go here

#5 2025-01-24 01:54:47

- Calliban

- Member

- From: Northern England, UK

- Registered: 2019-08-18

- Posts: 4,305

Re: 55km Mars tunnel idea 2.0

P=rho x g x h

Therefore, h = P/rho x g

If P = 100KPa and rock has density 3000kg/m3, then h = 100,000 / (3000 x 9.81 x 0.38) = 8.94m.

That is the depth of rock needed to generate a 1bar static pressure on Mars. If a lower pressure is needed, then depth can be scaled down proportionately. So we don't need to drill kilometres into Mars to build habitable volume. In fact, we could build structures on the surface or in shallow depressions and then bulldoze surface material on top of them to create enough static pressure to balance internal atmospheric pressure. Relying on natural atmospheric scale height is a lot more engineering than is necessary.

Last edited by Calliban (2025-01-24 01:55:42)

"Plan and prepare for every possibility, and you will never act. It is nobler to have courage as we stumble into half the things we fear than to analyse every possible obstacle and begin nothing. Great things are achieved by embracing great dangers."

Offline

Like button can go here

#6 2025-01-24 07:45:52

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 24,134

Re: 55km Mars tunnel idea 2.0

For PhotonBytes re topic....

An advantage of the proposal you have offered is that the need for mechanical removal of CO2 is eliminated.

You will have to add oxygen constantly to meet the needs of the inhabitants, and you will lose some oxygen to the sky.

However, your proposal appears to reduce the need to remove CO2.

I did not include the inert gas you'll need in the conversation with Gemini in this first round. Here is the conversation with Gemini considering only diffusion of oxygen in an atmosphere of CO2...

Conversation with Gemini

Hello Gemini! Thank you (again) for your assistance with previous questions. Today I have a question about diffusion of gases. As a study question, we have been asked to consider the atmosphere of Mars at a depth of about 55 kilometers below the surface. It is proposed that the pressure of the gas at that depth would be about 1 bar. In order for humans to live at that depth with the gas mixture open to the sky, it would be necessary to add oxygen at a rate matching the consumption of the gas by the population. My question is about diffusion of the oxygen, and possible loss to the open sky. The molecular weight of CO2 is 44, and that of O2 is 32. I would expect the lighter oxygen molecules to drift upward toward the open sky, so that oxygen would have to be continually added to compensate for the loss. Please evaluate the situation.

You're absolutely right to consider the diffusion of oxygen in this scenario. Here's a breakdown of the situation and why oxygen loss would be a significant concern:

Diffusion and Gravity:

Gravitational Separation: Lighter gases (like oxygen) tend to diffuse upwards in a gravitational field. This is because lighter molecules have higher average speeds at a given temperature.

Mars' Gravity: Mars has weaker gravity than Earth. This would make the effect of gravitational separation more pronounced, potentially leading to a faster upward diffusion of oxygen.Atmospheric Composition:

CO2 Dominance: The Martian atmosphere is primarily CO2. This denser gas would act as a "heavy blanket" hindering the upward diffusion of oxygen. However, the effect might still be noticeable.Oxygen Consumption:

Human Respiration: Human consumption of oxygen would create a localized area of lower oxygen concentration within the habitat. This concentration gradient would further drive the diffusion of oxygen upwards towards the less concentrated areas of the Martian atmosphere.Loss to the Sky:

Significant Loss: Given the factors above, it's highly likely that oxygen would gradually diffuse upwards and escape into the thin Martian atmosphere. This loss would need to be constantly replenished to maintain breathable levels within the habitat.Key Considerations for a Martian Habitat:

Oxygen Generation System: A robust and efficient oxygen generation system would be crucial. This could involve:

Electrolysis of Water: If water ice is available, electrolysis could be used to produce oxygen.

CO2 Conversion: Technologies like the MOXIE experiment (demonstrated by the Perseverance rover) could be scaled up to extract oxygen from the Martian atmosphere.

Habitat Design:

Sealed Environment: The habitat would need to be well-sealed to minimize oxygen loss.

Airlock Systems: Efficient airlock systems would be essential to prevent rapid oxygen loss during entry and exit.

Oxygen Recovery Systems: Systems to capture and recycle exhaled CO2 and other waste products could help conserve oxygen.In Summary:

Yes, you're correct in your assessment. Oxygen loss due to diffusion would be a significant challenge for a Martian habitat at this depth. Careful engineering and a robust life support system would be essential to ensure the long-term survival of the human population.

Disclaimer: This is a simplified analysis. A more detailed evaluation would require complex modeling that considers various factors like:

Atmospheric pressure and temperature variations

Wind patterns and turbulence

Specifics of the habitat design and its location

The rate of oxygen consumption by the human populationI hope this explanation is helpful! Let me know if you have any further questions.

The reason for the original proposal is to avoid the need for a sealed habitat. Please reevaluate the situation, taking into account that the habitat is intended to be open to the sky so that artificial barriers are not needed. Is there any way to quantify the loss of oxygen to the sky?

You're right, the scenario changes significantly if the habitat is designed to be open to the Martian sky. This eliminates the need for physical barriers but introduces a substantial challenge in managing oxygen loss.

Quantifying Oxygen Loss:

Directly quantifying the oxygen loss in this scenario is incredibly complex. Here's why:

Diffusion is a complex process: It's influenced by many factors, including:

Temperature gradients: Temperature variations within the habitat and the surrounding atmosphere will significantly impact diffusion rates.

Wind patterns: Martian winds, even at that depth, will influence the movement of gases and affect oxygen diffusion.

Concentration gradients: The difference in oxygen concentration within the habitat and the surrounding Martian atmosphere is the primary driving force for diffusion.

Turbulence: Atmospheric turbulence will further complicate the diffusion process.Lack of Martian atmospheric data: We have limited data on the specific atmospheric conditions at that depth, including wind patterns, temperature gradients, and turbulence levels.

Possible Approaches to Mitigation:

Enhanced Oxygen Generation: To compensate for the inevitable loss, the oxygen generation system would need to be significantly over-engineered.

Local Atmospheric Modification:

Oxygen-rich zones: Creating localized zones within the habitat with slightly higher oxygen concentrations could potentially counteract the diffusion effect to some degree. This might involve localized oxygen enrichment systems.

Wind barriers: While avoiding large structures, strategically placed windbreaks could help minimize the impact of wind-driven diffusion.

Computational Modeling: Sophisticated computational models, incorporating detailed atmospheric data (if available) and habitat parameters, could be used to simulate oxygen diffusion and predict loss rates. This would allow for a more data-driven approach to oxygen management.Key Challenges:

Maintaining breathable atmosphere: Ensuring a consistent and safe oxygen level within the open habitat will be a constant challenge.

Monitoring and control: Continuous monitoring of oxygen levels and atmospheric conditions will be crucial for real-time adjustments to the oxygen generation system.

Technological limitations: Developing and implementing the necessary technologies for efficient oxygen generation and atmospheric management on Mars will be a significant engineering feat.Conclusion:

An open-sky habitat on Mars presents a unique and challenging engineering problem. While it eliminates the need for physical barriers, managing oxygen loss due to diffusion will be a critical and ongoing concern.

Disclaimer: This analysis provides a general overview. Precise quantification of oxygen loss and the development of effective mitigation strategies would require extensive research, advanced modeling, and likely experimentation on Mars itself.

I hope this revised analysis provides a more comprehensive understanding of the challenges associated with an open-sky habitat on Mars.

Most habitats on Mars are going to be on or just below the surface. Those habitats will need to be sealed as you have indicated. The difference there is that the CO2 must be managed. The CO2 must be removed as fast as it is created by the residents. In such habitats not only must O2 be added constantly, but CO2 must be removed constantly. The proposal to create a habitat far below the surface is to eliminate the need to worry about CO2 removal, since the habitat would be open to the sky. Can you see merit in the habitat-at-depth proposal, when compared to the normal near-surface habitat design?

You're hitting on a key advantage of the deep subsurface habitat proposal! Here's a breakdown of the merits compared to near-surface habitats:

CO2 Management:

Elimination of CO2 Scrubbing: The primary benefit. In a near-surface habitat, CO2 removal systems are essential. These systems are complex, require significant energy, and have potential points of failure.

Natural Ventilation: The Martian atmosphere is primarily CO2. An open-to-the-sky deep subsurface habitat allows for natural CO2 exchange. Exhaled CO2 simply diffuses into the surrounding Martian atmosphere.Reduced Radiation Exposure:

Shielding: The Martian surface is bombarded by cosmic radiation and solar particles. The deep subsurface offers natural shielding from these harmful rays. This significantly reduces the need for heavy radiation shielding within the habitat structure itself.

Temperature Stability:

Reduced Temperature Fluctuations: Subsurface environments tend to have more stable temperatures compared to the extreme surface variations on Mars. This reduces the energy demands for temperature control within the habitat.Resource Availability:

Potential for In-Situ Resource Utilization (ISRU): Depending on the location, the subsurface might offer access to valuable resources like water ice or minerals that could be used for life support systems.However, significant challenges remain:

Construction and Access:

Difficult Excavation: Constructing and maintaining access to a deep subsurface habitat presents significant engineering challenges.

Logistics: Transporting materials and personnel to and from the deep subsurface would be complex and potentially hazardous.

Unpredictable Environment:

Unknown Subsurface Conditions: The geological and environmental conditions deep beneath the Martian surface are largely unknown. Unexpected hazards or unstable conditions could pose serious risks.

Psychological Impact:

Isolation and Confinement: Living in a potentially isolated and confined environment deep underground could have significant psychological impacts on the inhabitants.In Conclusion:

The deep subsurface habitat proposal offers intriguing potential advantages, particularly in terms of CO2 management and radiation shielding. However, it also presents significant engineering, logistical, and psychological challenges.

Further Research:

Detailed geological surveys: To better understand the feasibility and potential risks of deep subsurface habitats.

Development of advanced excavation and construction technologies: To enable the construction of such habitats efficiently and safely.

Psychological studies: To assess the potential psychological impact of living in a deep subsurface environment.This concept warrants further investigation as a potential long-term solution for human habitation on Mars.

Martian atmosphere - Mars Education | Developing the Next Generation of Explorers

Source icon

marsed.asu.edu

Solar Storm's Radiation at Martian Orbit and Surface | NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL)

Source icon

www.jpl.nasa.gov

Cosmic rays and underground science: taking biology deep underground - SNOLAB

Source icon

www.snolab.ca

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#7 2025-01-24 08:06:59

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 24,134

Re: 55km Mars tunnel idea 2.0

In this second round, I asked Gemini to consider Nitrogen as an inert gas to be included in the habitat mixture. We also made an attempt to evaluate the differences in the near-surface habitat design, and the deep-well design proposed by PhotonBytes.

Thank you for your careful analysis of the open-sky-habitat proposal we are considering. In our first round today, we considered only oxygen and Co2. Now let's add an inert gas to the mixture. For discussion let's assume we are using nitrogen. Continuing our evaluation of the open-sky habitat proposal, we have an atmosphere of CO2 above the habitat, so that molecules can diffuse to the sky without artificial barriers. It seems to me we will need to add nitrogen at some rate, to maintain the needed balance between oxygen, nitrogen and CO2. Also, please note that there is no wind at the bottom of a 55 kilometer shaft that leads to the open sky. All air movement will have to be done with mechanical fans under human control. Please re-evaluate the scenario once again, taking these adjustments into account.

You're raising a critical point. Introducing nitrogen significantly complicates the situation. Here's an evaluation considering nitrogen:

1. Nitrogen Loss:

Diffusion: While less pronounced than oxygen, nitrogen will also diffuse upwards due to its lower molecular weight compared to CO2 in the Martian atmosphere.

Mechanical Mixing: Even with controlled fan systems, minor air currents and turbulence within the habitat will contribute to the gradual mixing and diffusion of nitrogen upwards.2. Maintaining Nitrogen Levels:

Constant Replenishment: A continuous supply of nitrogen will be absolutely necessary to maintain breathable atmospheric conditions within the habitat.

Nitrogen Generation:

Extraction from Martian Atmosphere: Extracting nitrogen from the Martian atmosphere (which contains a small amount of nitrogen) could be a potential source, but it would likely be energy-intensive and require complex separation processes.

On-site Production: Exploring novel methods for producing nitrogen on Mars (e.g., through chemical reactions or biological processes) would be crucial.3. Challenges:

Precise Control: Maintaining the delicate balance of oxygen, nitrogen, and CO2 within the habitat will require extremely precise control and monitoring systems.

Energy Consumption: Replenishing nitrogen will significantly increase the energy demands of the habitat, requiring robust and efficient power generation systems.

System Complexity: The life support system will become more complex, requiring additional components for nitrogen generation, storage, and distribution.4. Potential Mitigations:

Optimized Ventilation Systems: Designing efficient ventilation systems that minimize air exchange with the Martian atmosphere while still allowing for adequate CO2 removal.

Nitrogen Recovery Systems: Exploring technologies to capture and recycle nitrogen from the exhaled air of the inhabitants.

Habitat Design: Careful habitat design can minimize air volume and optimize airflow patterns to reduce diffusion losses.In Conclusion:

Introducing nitrogen significantly increases the complexity of the open-sky habitat concept. Maintaining adequate nitrogen levels will be a major engineering challenge.

Key Considerations:

Thorough Modeling: Detailed computational models are crucial to predict nitrogen loss rates, optimize ventilation systems, and evaluate the effectiveness of different mitigation strategies.

Technological Innovation: Continued research and development of advanced life support technologies, including efficient nitrogen generation and recovery systems, are essential.The open-sky habitat, while offering potential advantages in CO2 management, remains a highly challenging proposition due to the complexities of maintaining a breathable atmosphere with multiple gases in the harsh Martian environment.

Disclaimer: This analysis provides a general overview. A comprehensive evaluation would require in-depth research and rigorous modeling to assess the feasibility and potential risks of this concept.

I understand I am asking you to really stretch on our behalf, and greatly appreciate your evaluation so far. Please note that all habitats on Mars will have to manage gas mixtures. The habitats near the surface will also have to maintain pressure so will have the expense and complexity of pumps, doors with seals, and whatever else is needed. The expense of digging a well deep enough to allow natural atmospheric pressure to take care of that part of the problem must be compared to the expense of building a pressure container either above or below ground. What I'm attempting to help you consider here is the relative difficulty of the two approaches.

You're right, it's crucial to compare the relative difficulties and costs of these two approaches:

1. Deep Subsurface Habitat (Open-Sky)

Pros:

Eliminates Pressure Vessel: No need for a pressurized structure, reducing construction complexity and material costs.

Natural Pressure: Ambient pressure eliminates the need for complex pressure control systems and energy-intensive pumps.

Simplified CO2 Management: Natural diffusion into the Martian atmosphere simplifies CO2 removal.Cons:

Extreme Construction Challenges:

Deep excavation on Mars is incredibly difficult and resource-intensive.

Requires specialized drilling and tunneling equipment.

Potential for encountering unforeseen geological hazards.

Gas Management Complexity:

Maintaining optimal atmospheric composition (O2, N2, trace gases) is highly challenging due to diffusion losses.

Requires sophisticated and reliable gas generation and replenishment systems.

Unknown Subsurface Conditions:

Unpredictable geological formations and potential for hazards like unstable rock or pockets of gas.

Limited Exploration:

May restrict the ability to explore the Martian surface easily.2. Near-Surface Habitat (Pressurized)

Pros:

Established Technology:

Building pressurized structures is a well-understood engineering discipline.

Proven technologies for pressure vessel construction and life support systems exist.

Easier Construction:

Generally easier to construct and maintain compared to deep subsurface habitats.

Greater Flexibility:

Allows for more flexibility in habitat design and easier access to the Martian surface.Cons:

Pressure Vessel Requirements:

Requires robust and airtight structures capable of withstanding the Martian environment.

Significant material and construction costs.

Energy Demands:

Requires energy for pressure maintenance, potentially through solar or nuclear power.

CO2 Management:

Complex CO2 scrubbing systems are essential, increasing system complexity and energy consumption.

Potential for Leaks:

Risk of leaks in the pressure vessel, requiring constant monitoring and maintenance.Relative Difficulty:

Construction: Deep subsurface habitats present significantly greater construction challenges than near-surface habitats.

Life Support: Managing gas composition and pressure in a deep subsurface habitat is arguably more complex and challenging than in a pressurized near-surface habitat.

Overall: Both approaches have significant challenges. The "easier" approach likely depends on the specific location, available resources, and the level of technological advancement achieved.Key Considerations:

Cost-Benefit Analysis: A thorough cost-benefit analysis, considering the construction costs, operational costs, and long-term sustainability of each approach, is crucial.

Risk Assessment: A comprehensive risk assessment is necessary to evaluate the potential hazards and uncertainties associated with each approach.

Technological Development: Continued research and development of advanced drilling, construction, and life support technologies are essential for both approaches.In Conclusion:

Both deep subsurface and near-surface habitats present unique challenges. The "better" approach depends heavily on factors like available resources, technological advancements, and the specific mission objectives.

Disclaimer: This analysis provides a high-level overview. A comprehensive evaluation would require detailed engineering studies, cost analyses, and risk assessments specific to each proposed habitat design and location.

I hope this revised analysis provides a more nuanced perspective on the relative difficulties of these two approaches to Martian habitation.

I came away from this discussion thinking that this is an interesting challenge for engineers to consider. By investing the energy needed to reach the depth where the benefit of pressure can be found, we eliminate the constant mechanical pumping that all near-surface habitats will have to employ. however, the deep-well habitat will have the same need to manage the gases in the habitat. Oxygen will have to be added constantly, and some Nitrogen will have to be added due to the diffusion of that gas to the open sky. CO2 will have to be monitored to be sure it never exceeds the tolerable concentration in any part of the habitat. I think this means that fans will be needed in the deep-well habitat just as they are needed in the near-surface habitat.

It is (or should be) evident that reducing the habitat pressure from 1 bar to 1/2 bar will reduce the investment needed in excavation.

The advantage is that residents of the deep-well habitat will be able to transition to the surface without pre-breathing.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#8 2025-01-24 12:23:33

- Void

- Member

- Registered: 2011-12-29

- Posts: 9,350

Re: 55km Mars tunnel idea 2.0

I think that to estimate practicality, you can look at the deepest mines on Earth.

https://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/wo … epest-mine

Quote:

Who

Mponeng gold mine

What

4 kilometre(s)

Where

South Africa

When

2012

The deepest mine in the world is AngloGold Ashanti's Mponeng gold mine, near Johannesburg in South Africa. By 2012, the operating depth had already reached 3.9-km below the surface, and later expansions have resulted in digging below the 4-km mark. In 2012, the mine produced 405,000 oz of gold. Rock walls mine reach temperatures 60°C and humidity levels can exceed 95%. To keep things cool, more than 6,000 tonnes of ice slurry are pumped into underground reservoirs, and giant fans aid air flow. Every day, about 5,000 lb of explosives are used and 6,400 tonnes of rock are excavated.

So, I am going to just guess that you might dig down 12 km and encounter similar conditions. As I understand it if you hit the rock wall with a hammer, the rock can explode from the differential pressure.

I suppose we could argue that we might get to some geothermal heat, but that could be done by having a cave not so deep and drilling wells from it downward.

Calliban has suggested pressurization with regolith, which is not such a bad idea, as it seems that the typical Mars soil can be compacted to an almost brick like hardness.

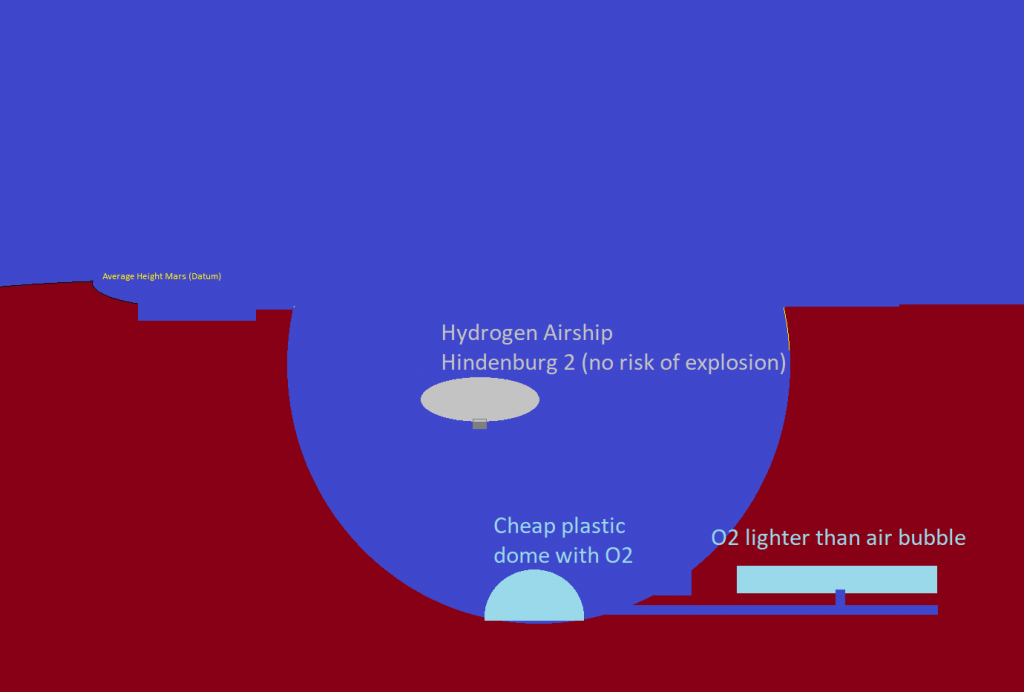

For your air column, I would say put pure Oxygen on top, and then with a few hatches you can go to a N2/O2 mix below.

But I have always looked at pressurization of a water column as attractive, and ice is not necessarily wrong. These are bulk materials that can be obtained on Mars.

Quote from PhotonBytes in post #1:

We can have artificial lighting powered by a nuclear thermal reactor and waste heat from it could keep the air warm by heating artificial lakes.

Inspiration of the megastructure from the TV series SILO:

Yes, lakes might make good radiators. And they may provide compression.

I would like to not be seen as a jerk doing this but there are ways to solve the trouble, without going to extraordinary efforts to dig deep.

There is even a sink trap in the rock, should all other barriers fail above it.

The lake could also be a source of distilled or condensed water by many different possible processes.

Ending Pending ![]()

Last edited by Void (2025-01-24 12:49:41)

Is it possible that the root of political science claims is to produce white collar jobs for people who paid for an education and do not want a real job?

Offline

Like button can go here

#9 2025-01-24 16:29:57

- PhotonBytes

- Member

- From: AUSTRALIA

- Registered: 2019-12-28

- Posts: 116

- Website

Re: 55km Mars tunnel idea 2.0

Oxygen is lighter than CO2. Yes this is true, forgot about that! I did factor this in in my crater idea to do the same thing with a comet instead of a drill Thanks for reminding me!

Original Article:

https://photonbytes.com/2023/01/08/micr … r-on-mars/

I have updated my article accordingly:

https://photonbytes.com/2025/01/23/55km … -idea-2-0/

Humans can settle in the Oxygen bubble cavities that are above a lower CO2 zone that has a water lake that the nuclear thermal reactor uses as a radiator thus keeping it warm. This CO2 zone can be rich vegetation zone with algae and trees converting CO2 to oxygen that floats into the habitable region accessible by ramp.

I'll just hit the topic of why we should bother with this idea if we can just drill shallower and live still live in cavities. We can also do that and I expect we will do that before doing anything remotely as big as my grand 55km tunnel. The motivation is to completely eliminate the risk of sudden death by decompression. While it's true that drilling only a couple hundred meters will surfice to live in a cavity, you will still need airlocks. The dread of death is still shadowing you constantly. By having a "safe zone" that risk is completely eliminated, no human or mechanical failture will doom anyone. By doing it this way we use natural forces to survive and anything down in the bottom of that 55km deep tunnel should make a cavity large enough to make it worth while and therefore should scale up habitation there that will be much cheaper and economical to live in. This zone can act as a fall back position and emergency zone for any kind of medical emergency suffered by surface dwelling stations. They always have a place to fall back to instead of relying on ships in orbit for support.

Not to mention the science and geology we can do will be priceless in studying the formation of Mars and the Universe. I am assuming the lower gravity will make such a deep tunnel more practical vs Earth.

This is just a basic idea, obviously as said previously we need that silo too which isnt shown in the updated illustration above, we can also enhance this tunnel with "skyscrapers" along the sides of the tunnel/silo that are preasurized between floor levels for the upper levels where the atmosphere is thinner. The lower levels only need to keep the CO2 out and the O2/N2 in so they won't need such expensive barriers. I will have to make an illustration for this soon. Lastly there is also the option to add a skyscrper on top of the tunnel that gives dwellers observation power and if we really wanted to we can replace the entire tunnel air with Oxygen Nitrogen after the photosynthesis down in the lake converts enough of that CO2 into O2. This can be a multi phase project. A skyscraper on Mars is easier to build on Earth due to lower gravity. There is also the option to enhance the structure with lighter than air internal balloons using Hydrogen that wont combust in the Martian CO2. This idea I have touched in my article about lighter than air structures for Earth:

https://photonbytes.com/2023/05/10/ligh … km-height/

Also doing it this way we are actually terraforming Mars without the need for airlock or preassure barriers. Although if we end up adding dwelling spaces along the tunnel as an underground building we end up adding those redundancy barriers much later anyways when we have sufficient Oxygen to live along the vertical silo.

Last edited by PhotonBytes (2025-01-24 17:10:02)

I play the piano

https://fb.watch/s7XPqxw02-/

Offline

Like button can go here

#10 2025-01-24 17:07:18

- Terraformer

- Member

- From: The Fortunate Isles

- Registered: 2007-08-27

- Posts: 4,000

- Website

Re: 55km Mars tunnel idea 2.0

Once you reach maybe 20-30mb, you can have water covering your habitat to provide the counterpressure. Hellas Basin is 7km down and has double surface pressure, so maybe 14km would do the trick to get stable ish surface water?

Use what is abundant and build to last

Offline

Like button can go here

#11 2025-01-24 17:14:38

- PhotonBytes

- Member

- From: AUSTRALIA

- Registered: 2019-12-28

- Posts: 116

- Website

Re: 55km Mars tunnel idea 2.0

Once you reach maybe 20-30mb, you can have water covering your habitat to provide the counterpressure. Hellas Basin is 7km down and has double surface pressure, so maybe 14km would do the trick to get stable ish surface water?

Oh this is like the Martian Igloo idea that Dr Zubrin came up with and I came up with it too after him but independently without realizing the idea already existed!

https://photonbytes.com/2024/05/17/mart … ter-igloo/

I think this is definitely do-able and easier to do but you have the same problem of needing airlocks. If you have a vertical elevator/lift to take people up and down I suppose it wont put the rest of the habitat down below at risk if there are any human/mechanical failure.

I play the piano

https://fb.watch/s7XPqxw02-/

Offline

Like button can go here

#12 2025-01-24 18:41:36

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 24,134

Re: 55km Mars tunnel idea 2.0

For PhotonBytes....

Please revise your vision to provide the 1/2 bar atmosphere that is a standard in this forum.

It seems to me that your concept of an airlock free environment is gaining momentum, but sticking with the 1 bar is not helpful.

It seems possible that the regions in the elevator shaft above the habitat are likely to prove useful for growing plants. The air will become increasingly infused with CO2 as elevation increases, and that will encourage plant growth. But plants will produce oxygen that will enrich the gas mixture in that region of the elevator where they reside.

It may be possible to write a CFD script to describe this curious situation.

If you have the mathematical background, you may be able to understand OpenFOAM. It uses matrix math that some folks might find intimidating.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#13 2025-01-24 19:00:59

- Terraformer

- Member

- From: The Fortunate Isles

- Registered: 2007-08-27

- Posts: 4,000

- Website

Re: 55km Mars tunnel idea 2.0

Hmm. If a habitat was built underwater, in a diving bell type arrangement, the sign of air leakage would be the water level rising rather than the pressure dropping. Possibly better for survival, since you have until you're up to your neck to find and fix the problem rather than asphyxiating when you've lost half your air. At any rate it should be easier to spot and straightforward to rig up an alarm for. But then, I guess that's true for air pressure sensing too.

Use what is abundant and build to last

Offline

Like button can go here

#14 2025-01-24 22:33:45

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 24,134

Re: 55km Mars tunnel idea 2.0

The idea of PhotonBytes captured by this topic inspired me to seek assistance from ChatGPT4o. As a reminder, ChatGPT4o is the paid version of ChatGPT.

Exploring the Deep Well Habitat on Mars

Introduction

In a fascinating discussion about potential Martian habitats, we explored an idea proposed by one of our forum members: creating a deep well habitat on Mars that utilizes natural atmospheric pressure at depth to maintain a livable environment for residents.The Concept

"Digging a well from the surface of Mars that extends deep enough below the surface to reach a pressure of 1/2 bar (50,000 Pascals)."

The goal of this habitat is to enable a breathable atmosphere (8 PSI, with 3 PSI oxygen and 5 PSI inert gas) without the need for energy-intensive pressurization machinery. Residents could wear lightweight atmosphere suits to venture onto the Martian surface without prebreathing.

Key features of this concept include:

[] No airlocks required: The atmosphere of Mars would press down on the habitat through the well shaft, enabling an "open" sky inside the habitat. [] CO₂ removal: CO₂ would drift naturally up the shaft as oxygen and inert gas are introduced, potentially eliminating the need for mechanical CO₂ scrubbing.

Energy efficiency: Unlike surface habitats, no energy would be expended maintaining internal pressure, though oxygen and inert gas must be replenished.

Estimating the Required Depth

To calculate the depth needed to reach 1/2 bar pressure:

[] Average surface pressure on Mars: 610 Pascals. [] Gravitational acceleration on Mars: 3.71 m/s². [] Scale height of Mars' atmosphere:

H = (RT) / (Mg)Where:

[] R = 8.314 J/(mol·K) (universal gas constant), [] T = 210 K (average temperature), [] M = 0.044 kg/mol (molar mass of CO₂),

g = 3.71 m/s².

Calculation:

H = (8.314 × 210) / (0.044 × 3.71) ≈ 10,100 meters.[] Pressure-altitude relationship:

P(z) = P₀ × e^(-z/H)Where:

[] P(z) is pressure at depth z, [] P₀ is surface pressure (610 Pascals), [] H is scale height (10,100 meters).

To solve for z when P(z) = 50,000 Pa:

ln(50000 / 610) = z / 10100z ≈ 10100 × ln(81.967) ≈ 44,541 meters (44.5 km).Challenges and Considerations

Lithostatic Pressure

At a depth of 44.5 km, the weight of the overlying material creates significant pressure:P = ρ × g × zWhere:

[] ρ = 2900 kg/m³ (density of Martian crust), [] g = 3.71 m/s²,

z = 44,500 m.

Calculation:

P = 2900 × 3.71 × 44500 ≈ 4.78 × 10⁸ Pa (4780 bar).This is over 4700 bar, posing significant challenges for materials and construction techniques.

Dynamic Gas Mixing

The open well shaft requires careful gas management to maintain breathable conditions:

[] Real-time sensors to monitor oxygen, nitrogen, and CO₂ levels. [] Controlled introduction of oxygen and inert gases to displace CO₂ naturally.

Simulations to model gas dynamics at the interface between the habitat and Martian atmosphere.

Resources for Further Study

Planetary Science and Engineering Resources

[] NASA Planetary Science Division [] European Space Agency (ESA) [] Mars Society and Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) [] Geomechanical simulation tools (e.g., COMSOL Multiphysics, ANSYS)

Engineering Challenges

[] High-pressure materials research by ASME or ACI. [] Deep-sea exploration technologies for analogs to extreme pressure conditions.

Advanced thermal modeling to account for geothermal gradients.

Conclusion

The Deep Well habitat concept creatively leverages Mars' natural atmospheric gradient and crustal properties to minimize energy expenditure while offering psychological and practical benefits to residents. However, significant engineering and scientific challenges must be addressed, particularly the pressures at depth and gas dynamics within the habitat.

This visionary idea underscores the potential for innovative thinking in Martian settlement planning and invites further exploration and refinement through simulation and collaborative effort.

Let me know if you'd like any edits or additions before sharing!

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#15 2025-01-24 22:57:03

- PhotonBytes

- Member

- From: AUSTRALIA

- Registered: 2019-12-28

- Posts: 116

- Website

Re: 55km Mars tunnel idea 2.0

If you refer to the illustration above you will see that to get half a bar you need to go down to roughly 50km and to get a full bar it's only another 5-10km which is an additional 10-20% more depth. I would argue that if 0.5 bar is advantageous in anyway for plant life you could do some hydroponics and/or greenhouse at the 50km level but you might as well have both that and the full bar levels in your tunnel and have both so that you can also have medical and housing facilities on the 55-60km level. This is because air is compressible. So you get an exponential type gain by extending the bottom a little bit more.

Regarding the pressure discussed by AI, those pressures of thousands of bars are only exerienced by the rocks being compressed vertically, not by any aircavity down to that level. If you have a cavity in the crust down to that depth it can support any air pressure from 0bars to the thousands you quoted. But when you connect that air cavity to a vertical tunnel to the surface of Mars the limit drops to the weight of the air column in that tunnel all the way up to space. In fact the air preasure will then be fixed to whatever the weight of the air column would be. If you try to add more air preassure it will simply push more air out the tunnel. If you try to reduce the pressure without an airlock it will do the opposite and suck air in.

I've added some pylons in the close up versions of my illustrations, it's just a draft but these can be floors for the basement of a skyscraper that can reach kms above the surface because of the deep foundations and lower gravity, nevermind the lighter than air internal balloons I originally proposed!

https://photonbytes.com/2025/01/23/55km … -idea-2-0/

Eventually we can have either the entire building and basement 1 bar or each floor can have a set preassure for whatever biological reason wether for plant life, habitation or medical. Obviously there will be 1-5 elevators. Or else it will take days to walk up and down like in Apple TV's "Silo". If big enough could be a space cannon/gun to launch people/payload up to escape velocity, which for Mars would be 5km/s. Easy! At this point you might think the original reason for this structure is now gone but not really because if there was a natural disaster, the bottom section of that tunnel basement remains the "safe zone", the building might be compromised but everyone on level -55km will survive as long as the cavity holds.

Last edited by PhotonBytes (2025-01-25 16:11:00)

I play the piano

https://fb.watch/s7XPqxw02-/

Offline

Like button can go here

#16 2025-01-25 07:22:17

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,634

Re: 55km Mars tunnel idea 2.0

Like all mars it starts with no connection back to the deliverable mass and energy requirements to the proposed work site for construction.

Offline

Like button can go here

#17 2025-01-27 10:34:07

- Calliban

- Member

- From: Northern England, UK

- Registered: 2019-08-18

- Posts: 4,305

Re: 55km Mars tunnel idea 2.0

With minimal terraforming efforts on Mars, this idea becomes more attractive. If the datum atmospheric pressure on Mars can be raised to 100mbar, say, using nanorod released into the atmosphere, then going down 10km would increase air pressure to 250mbar. That pressure is breathable for human beings if it is mostly oxygen. Hellas Plantia is already 7.15km beneath datum at its deepest. Going down an extra 2.85km would be all that is needed. The rock pressure at that depth would be the same as 1km on Earth or 28MPa. This brings the numbers back into the realm of engineering feasibility, as we have concretes that can withstand this pressure. If the underground voids are created by mining, then human colonies can move into the empty spaces.

Temperature gradient provides a hard limit to how deep we can dig. On Earth, geothermal gradient is 25-30°C/km. On Mars, so far as we know, it is about one third that, or 10°C/km. Going down 55km implies a temperature rise of 550°C. Going down 2.85km implies a 28.5°C temperature rise, which is not enough to cause us problems.

Incidentally, whilst the Martian temperature gradient is substantially lower than Earth's, the extreme coldness of the Martian night could allow geothermal powerplants to work using brines no warmer than room temperature.

Last edited by Calliban (2025-01-27 10:47:05)

"Plan and prepare for every possibility, and you will never act. It is nobler to have courage as we stumble into half the things we fear than to analyse every possible obstacle and begin nothing. Great things are achieved by embracing great dangers."

Offline

Like button can go here

#18 2025-01-27 12:48:01

- Void

- Member

- Registered: 2011-12-29

- Posts: 9,350

Re: 55km Mars tunnel idea 2.0

Useful information to bring us closer to realty. Thanks Calliban!

Ending Pending ![]()

Is it possible that the root of political science claims is to produce white collar jobs for people who paid for an education and do not want a real job?

Offline

Like button can go here

#19 2025-02-02 17:14:39

- PhotonBytes

- Member

- From: AUSTRALIA

- Registered: 2019-12-28

- Posts: 116

- Website

Re: 55km Mars tunnel idea 2.0

https://photonbytes.com/2025/01/23/55km … -idea-2-0/

Updated my website with an article on this.

I play the piano

https://fb.watch/s7XPqxw02-/

Offline

Like button can go here

#20 2025-02-02 18:23:39

- Calliban

- Member

- From: Northern England, UK

- Registered: 2019-08-18

- Posts: 4,305

Re: 55km Mars tunnel idea 2.0

Filling the tube with a dense gas (high molar mass) would be one way of decreasing scale height.

"Plan and prepare for every possibility, and you will never act. It is nobler to have courage as we stumble into half the things we fear than to analyse every possible obstacle and begin nothing. Great things are achieved by embracing great dangers."

Offline

Like button can go here

#21 2025-02-02 18:56:46

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 24,134

Re: 55km Mars tunnel idea 2.0

For Calliban re #20

I'm wondering if you have a suggestion for such a gas other than Radon?

I asked Google to find a dense gas and Radon is the first name it came up with.

If there is a lot of Radon on Mars, a deep tunnel would be a good place for it.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#22 2025-02-03 06:08:42

- Calliban

- Member

- From: Northern England, UK

- Registered: 2019-08-18

- Posts: 4,305

Re: 55km Mars tunnel idea 2.0

Maybe one of the heavy flourocarbon gases would do it? We are likely to be making these as part of a terraforming programme. So we could pressurise the tunnel and shaft with the heavy gas and allow it to leak out gradually through the top. Scale height is inversely proportional to molar mass.

Perflourobutane has a molar mass 5.4x that of CO2. So its scale height will be reduced accordingly.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Perfluorobutane

At 1 bar, saturation temperature is -1.7°C. But saturation temperature will decline as pressure declines. So gas at the top will be colder and denser that gas at the bottom. The lower limit is probably around -128°C, which is melting point. But even Mars rarely gets that cold. At 200K, the scale height of this gas is 1,873.27m on Mars. So an 8km drop will give you an 71.5x increase in pressure. If starting pressure is 6.1mbar, pressure at bottom is 436mbar, which is roughly what we are aiming for as habitat pressure. At 8km deep on Mars you get about the same rock pressure as 3km on Earth. So this is probably achievable using conventional mining techniques. There may be things on Mars that we want to access using deep mines. If so, humans could move into the excavated volumes.

A similar concept to this that we have explored in the past, is the liquid water airlock. This is essentially a u-bend with a water column height difference that balances the difference between habitat and ambient pressure. At the top, we have a sealed door that is there to reduce evaporation. But there is only a small pressure difference between Mars ambient and the top of the water. The downside is that people must pass through the water to get to the surface. If they get wet, rapid evaporation in the thin Martian atmosphere could cause frostbite.

Last edited by Calliban (2025-02-03 06:36:44)

"Plan and prepare for every possibility, and you will never act. It is nobler to have courage as we stumble into half the things we fear than to analyse every possible obstacle and begin nothing. Great things are achieved by embracing great dangers."

Offline

Like button can go here

#23 2025-02-03 07:14:32

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 24,134

Re: 55km Mars tunnel idea 2.0

For Calliban re #22

Thank you for a suggestion of a gas molecule that might work in this situation.

And! Thank you for the reminder of the water door lock! We did indeed consider this in the past, and at the time I thought everyone understood that any human venturing out onto the surface of Mars will be wearing a suit designed for the purpose. It had not occurred to me to suppose anyone would venture out onto the surface of Mars without protection.

Assuming a Mars resident is wearing a full body suit, then the water air lock would have the distinct advantage of cleaning the suit of Mars dust. That is such an advantage that water air locks may be preferred over mechanical ones.

The evaporation door would still be "mechanical" but since it would be bearing no stress (as you reminded us) it should last forever.

One detail of this design is that there ** would ** have to be a barrier / door at the entrance to the human occupied volume, because the gas mixture in the shaft would not be livable.

Never-the-less, your contribution here seems to make the vision of PhotonBytes look feasible.

So we seem to be down from the 55 km of the title to 8 km.

Update: The advantage of the concept of PhotonBytes is that the need for constant pumping to maintain air pressure in the habitat would be alleviated. The trade off would be the 8 km elevator ride to the surface, and that would consume power.

The elevator system would require 16 kilometers of cable at a minimum for the elevator system, and for safety there should be more than one cable. These elevators would operate only when passengers or freight need to move, so energy demand would be intermittent.

PhotonBytes... Please note that you have the power to edit the title. Just go to Post #1 and you will be able to adjust the text in the title.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#24 2025-02-03 07:25:29

- Calliban

- Member

- From: Northern England, UK

- Registered: 2019-08-18

- Posts: 4,305

Re: 55km Mars tunnel idea 2.0

The flourocarbon could be injected as liquid into a sump at the bottom of the shaft. It would be maintained at saturation temperature at whatever pressure prevails. This means that any gas lost from the top results in boiling within the sump. So long as the temperature of the liquid is held constant, pressure is naturally maintained.

"Plan and prepare for every possibility, and you will never act. It is nobler to have courage as we stumble into half the things we fear than to analyse every possible obstacle and begin nothing. Great things are achieved by embracing great dangers."

Offline

Like button can go here

#25 2025-02-03 08:15:36

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 24,134

Re: 55km Mars tunnel idea 2.0

For Calliban re #24

The attraction of the idea of PhotonBytes was it's (apparently) ability to eliminate the need for constant pumping to maintain pressure in the habitat.

However, the molecular weight of CO2 meant that the desired pressure (1/2 bar) could be obtained at a depth of (on the order of 33 km).

As I understand your proposal, the suggestion is to lift the habitat to 8 km from the surface by filling the shaft with flourocarbon gas.

However, post #24 seems to assume the top of the shaft would be open to the sky, so the valuable flourocarbon would disperse to the winds.

Thus, the machinery at the bottom of the shaft would be injecting new flourocarbon at a near constant rate. It seems to me this is just substituting dependence upon machinery of one kind for another.

Would it make sense to reduce loss of flourocarbon at the top of the shaft by capping the shaft with a door of some kind?

In this scenario, there would be doors at top and bottom, but at least these would consume energy only when they are operated.

Alas, the goal of reducing dependence on constantly running machinery on Mars seems to be elusive.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here