New Mars Forums

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

Announcement

#1776 2024-03-23 12:32:42

- RobertDyck

- Moderator

- From: Winnipeg, Canada

- Registered: 2002-08-20

- Posts: 7,934

- Website

Re: Starship is Go...

That adds weight, complexity in manufacturing, cost, and more failure modes to design-around. The X-33 program failed because of that, and because they tried to design to way too low an inert weight fraction.

I disagree. NASA had ensured all components were tested on something else before integration. Lockheed-Martin made a last minute change from a solid wall composite tank to hollow wall honeycomb structure. The tank was tested with liquid nitrogen. When it was drained and warmed it failed. Analysis showed the paper thin walls developed hairline cracks that let LN2 into cells of the honeycomb structure. When it was drained and warmed the hairline cracks sealed shut due to thermal expansion. Then the LN2 boiled, causing the tank walls to explode from the inside. They also found students who assembled it used tape to hold carbon fibre in place during assembly. The tape was a weak point, it failed there. However, even if tape was not used it would have failed. Ok, lesson was hollow wall with paper thin walls is not compatible with cryogenic liquids. They should have gone back to the original design: solid wall composite.

But that's not what they did. NASA activated the clause in the contract that said any setback must be shared with the contractor. Lockheed-Martin didn't want to pay. Lawyers argued for years. They also tried to use the same aluminum alloy used in the 1960s. A change to aluminum made it too heavy. But lawyers continued to argue over who pays, all work stopped. Then a presidential election. George W. Bush was elected. He cancelled the whole thing.

This was corporate greed. NASA believed the last minute tank design change was deliberate to cause a cost overrun. The project got cancelled due to corporate greed.

Online

#1777 2024-03-24 09:09:45

- GW Johnson

- Member

- From: McGregor, Texas USA

- Registered: 2011-12-04

- Posts: 5,801

- Website

Re: Starship is Go...

Rob:

This is the same NASA that analyzed Challenger's cold booster O-ring performance as pressurized on a broad front, but built the booster with goo in the insulation joints, forcing the gas from the pressurizing booster to wormhole-through the goo at specific points, concentrating the O-ring-snapping effect greatly.

This is the same NASA that developed a shuttle tile patching kit, but never flew it (might not have worked for a hole in the leading edge, I know that). This is the same NASA that did not tell Challenger's crew there were concerns about damage. And who refused to use available imaging from the ground to inspect for signs of that damage, when they already knew where to look from the launch coverage.

I don't doubt that Lockheed-Martin and NASA were at odds over costs an who was going to pay. That happens all the time in big corporation contracting.

My point is that news reports at the time indicated every time they stood one of those composite propellant tanks up on end, and tried to fill it, it cracked open of its own loaded weight! They simply tried to make them too lightweight. The airframe itself was never built, but was designed the same way, which did not portend well. For that thing to be an SSTO on LOX-LH2, at MR-effective dV = 9.5 km/s (launch plus losses, a rendezvous budget, and deorbit), and an (arbitrary small) 1% payload fraction, you would have a propellant mass fraction of 93.7% of ignition mass at an average ascent Isp of 350 sec. Less the effect of payload, that leaves you an inert mass fraction of only 5.3%. At Isp = 370 sec, the numbers are 92.7% propellant and 6.3% inert, hardly any different.

There are two problems with that: first, 5.3% is simply NOT AT ALL CREDIBLE for a vehicle that must also serve as as an entry spacecraft, AND must also somehow land horizontally, which is what they were trying to do! I would not consider 10% inert even remotely credible for that job, and certainly NOT in larger sizes, due to square-cube scaling effects. (And SpaceX is still running smack into that same non-credible low inert mass problem with their Starship.)

Second, the thing was to use a linear aerospike set of engines. This was supposedly to improve performance over fixed bells, and I still see that lie told today. Free-expansion nozzles of almost any kind work a little better than fixed bells up to the lower stratosphere. Above that, streamline divergence gets to be extreme, utterly killing your nozzle effective kinetic energy efficiency. They are absolutely LOUSY vacuum engines! There is NO WAY IN HELL to get an ascent-averaged Isp of 350 sec out of such a thing, even on LOX-LH2!

So the whole design was sold as corporate welfare, not anything that could actually be done. The published reports cover that up, of course. It doesn't take much figuring to verify that that job could not be done that way, and that figuring could have been done before issuing a contract, in an honest world. Ergo: it was all a lie from the get-go.

GW

Last edited by GW Johnson (2024-03-24 09:55:43)

GW Johnson

McGregor, Texas

"There is nothing as expensive as a dead crew, especially one dead from a bad management decision"

Offline

#1778 2024-03-24 11:25:30

- RobertDyck

- Moderator

- From: Winnipeg, Canada

- Registered: 2002-08-20

- Posts: 7,934

- Website

Re: Starship is Go...

My primary complaint is corporate executives screwing with it to deliberately cause cost overruns, and corporate lawyers deciding what the new tank should be. They should have let the lead engineer do the engineering.

Corporate welfare? I'm sure corporate executives saw it that way, which was part of the problem. NASA and the engineers wanted a working system.

NASA failed to tell Columbia crew about damage. And I have posted on this forum about that. One engineer who worked for a contractor for NASA complained to me about my criticism. But we agree on that. Challenger happened when they refused to listen to ATK engineers who said not to launch when weather was too cold.

I didn't think an aerospike engine would be efficient, but I've been wrong before. The XRS-2200 engines produced Isp=339 seconds at sea level, 436.5 seconds in vacuum. As comparison RS-25/SSME produced Isp=366 seconds at sea level, 452.3 seconds in vacuum. So...

Online

#1779 2024-03-24 14:55:39

- GW Johnson

- Member

- From: McGregor, Texas USA

- Registered: 2011-12-04

- Posts: 5,801

- Website

Re: Starship is Go...

Rob:

Actually, I think we agree more than we disagree, about any of these points.

Challenger: Management at NASA refused to listen to NASA engineers and Thiokol engineers. Thiokol management didn't listen to their own engineers, and backed NASA management's decision to ignore all the engineers and fly anyway. What some of the NASA engineers analyzed for cold O-ring performance (after the disaster, at the request of NASA management, to help justify their claim it was safe) was not the configuration that was actually built!

What was built behaved very much like the sample O-ring material that the physicist on the investigation board dipped in his ice water, and snapped in two with his thumbs and forefingers (a sharply concentrated load where the gas jet worm-holed through). The managers showed those calculations to the investigation board, then the physicist broke the sample in front of everybody on live TV, and so blew all their claims to hell. I watched that happen live. And cheered! He broke the attempted cover-up. (The same attempted cover-up that ruined Roger Boisjoly at Thiokol.)

Aerospike engines: I'm surprised the XRS 2200 engines are claimed to produced 339 s at sea level (that's too low for a free-expansion design with LOX-LH2) and 436 s in vacuum (that's far too high for a free expansion into vacuum, LOX-LH2 notwithstanding). To me, the reverse is more believable. In vacuum, the outer-edge streamlines should be turning off axis about 90 degrees. Kinetic energy efficiency ought to be on the order of 50%.

GW

Last edited by GW Johnson (2024-03-24 15:02:43)

GW Johnson

McGregor, Texas

"There is nothing as expensive as a dead crew, especially one dead from a bad management decision"

Offline

#1780 2024-03-24 15:00:09

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 7,857

Re: Starship is Go...

GW,

MasterBond - Epoxy Adhesives for Cryogenic Applications

MasterBond - List of Cryogenically Serviceable Epoxy Systems

That's a pretty extensive list. I agree with the point about requiring a fluoropolymer liner for LH2, because just about every material is permeable to LH2. I disagree that all epoxy materials become excessively brittle at cryogenic temperatures. Some do, but others don't. Most of this stuff I pointed out to you didn't exist when the X-33 was built, so it would've been difficult to design a vehicle using tech that didn't exist back then. The high modulus fiber and range of cryogenic-capable epoxies that exist today simply weren't available back then.

With engines and propellant tanks that didn't meet specifications, well... That's most of the vehicle right there, so we never had a viable launch vehicle design with the X-33. SSTO is an absolute fascination for some people, but after looking at the mass margins, it's very costly to actually do, if it can be done at all. Thus far, it hasn't been done. The Space Shuttle came the closest to the definition, but that was unaffordable, so now we've switched to the completely unaffordable SLS.

9X 2,000,000lbf thrust from LNG burning 3D printed F-1B engines for a reusable first stage, and an expendable upper stage or a reprise of the original Space Shuttle concepts which were not long cross-distance gliders, seem to be remarkably similar to what SpaceX actually built. The 9 engine booster is manageable, as SpaceX has proven with Falcon 9 / Falcon Heavy.

Mangalloy steel (51ksi to 130ksi yield strength, vs 39ksi for 304L) for the boosters, for which no acceptable weld techniques existed a mere 10 years ago, is about 30% less costly than 304L, and is now being used in cryogenic LNG and LOX applications, with testing now being conducted down to LH2 temperatures. The booster probably wouldn't be any lighter, but it would be a lot stronger. Now that we're starting to mess with CNTRP composites, CNTRP for a reusable upper stage, with proper heat shielding, and we can probably arrive at a vehicle that meets both mass and service temperature specifications at the same time.

That's about as much materials tech and design simplification as we can throw at the mass / service temperature / total vehicle complexity problem. 9X F-1Bs greatly reduce the booster stage's plumbing nightmare. Even cheaper and stronger weldable steel reduces booster production costs. The interior and exterior can be CVD coated with Silicon Nitride, so corrosion won't be an issue. It will provide a "shiny" apperance, similar to stainless steel, and will still be shiny after heating associated with the booster's plunge back through the atmosphere. A much lighter upper stage fabricated from CNTRP partially restores the payload mass fraction when the fully reusable upper stage attached. The upper stage isn't coming back from lunar or Mars missions in a practical way, until the ISRU tech exists to bring it back.

Offline

#1781 2024-03-24 15:24:55

- GW Johnson

- Member

- From: McGregor, Texas USA

- Registered: 2011-12-04

- Posts: 5,801

- Website

Re: Starship is Go...

Kbd512:

It comes down more to the engines than anything else. I did some comparisons of aerospikes and conventional bells, posted Feb 2023 on "exrocketman". For an aerospike fed by somewhat supersonic bells, followed by free expansion against the aerospike, I saw sea level performance equal to a compromise bell, and the aerospike only dropped down to about its sea level performance while in vacuum. It beat the conventional bell slightly in the lower stratosphere near 100,000 feet.

If you did a choked-only gas generator feeding all the expansion against the aerospike, vacuum performance was well below sea level performance for the aerospike. My point: the ascent-averaged Isp performance of any aerospike will be lower than the ascent-averaged performance of a conventional bell, precisely because ALL free-expansion nozzles have performance degradation in vacuum, due to streamline divergence off axial that is extreme.

Now, for a reusable SSTO, you need a lifting body airframe to serve as both re-entry vehicle, AND something you could at least land on a large dry lake bed at 250+ mph. The propellant tanks cannot conform to such a shape, they MUST be located inside of it. There is simply no way in hell one could possibly believe a 5-10% vehicle inert mass fraction is in the least credible, given the situation where the tanks CANNOT be the airframe. 15+, more believably 20%, maybe. Fancy higher-tech materials will make a small dent in that conclusion, but not a large one!

All you have to do is bound the problem with the rocket equation at the ridiculously-low payload fraction of 1%, using a realistic mission mass ratio-effective dV requirement near 9.5 km/s. Find the Isp that gets you a 15 or 20% mass fraction. It's in the low nuclear range, not any chemical known.

Yeah, expendable could be done, with the right engines, using LOX-LH2, precisely because we know how to build expendable stages in the 3-5% inert fraction range, with tanks that are the airframe. But NOT reusable! And that's the point I have been trying to make.

GW

Last edited by GW Johnson (2024-03-24 15:29:10)

GW Johnson

McGregor, Texas

"There is nothing as expensive as a dead crew, especially one dead from a bad management decision"

Offline

#1782 2024-03-24 16:49:45

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 7,857

Re: Starship is Go...

GW,

I agree with pretty much all of that. I'm not arguing for SSTO. I think TSTO is the most practical way to orbit for a fully reusable vehicle, even if you could somehow get SSTO to work. The only reusable SSTO design that might possibly work is the Sabre-engined Skylon, and the only reason that might be a bit more practical is because it flies to the edge of space using air-breathing engines, and then switches to rocket engines.

CNTRP can get the propellant tank mass fraction down, but it's only about twice as strong as CFRP in a practical vehicle design, so if you have 2 separate layers of material for the propellant tanks and airframe, then your mass fraction is no better than a CFRP reusable rocket with the tank being the airframe of the vehicle. There are no known lighter / stronger materials than CNTRP or BNNTRP ready for use and chemical rocket engine performance hasn't changed much since the Space Shuttle was created, so there are no mass / cost viable SSTOs, even with materials twice as strong as CFRP. As you said, it's an engine limitation.

That means the only marginally feasible SSTOs are powered by Sabre-like dual-cycle turbofan / rocket engines that draw Oxygen from the atmosphere to do what the booster stage normally does, and then switch to rocket power for the final push to orbit. The payload mass fraction of Skylon is still pitiful when compared to the "heavy metal" Starship, and it cannot be "made substantially better", precisely because the entire vehicle requires very heavy insulation to survive reentry. The airframe structural mass fraction is as low as it possibly can be with CNTRP and BNNTRP, so engine mass and thermal protection mass dominates. After you spend all that money on all the tech, you have a vehicle that's very costly to maintain, but it can theoretically do what a SSTO is supposed to do. The one thing it won't do is reduce costs.

The only case to be made for Skylon-like SSTOs is their potential to be safer to operate than monstrously powerful Starships, because they operate more like the Concorde than a super heavy lift rocket.

Offline

#1783 2024-03-25 09:44:35

- GW Johnson

- Member

- From: McGregor, Texas USA

- Registered: 2011-12-04

- Posts: 5,801

- Website

Re: Starship is Go...

Supposedly the SABRE engine is working in ground tests. That's what was once called a "liquid air cycle" engine design, and the bugaboos were rapid heat transfer and water condensation as ice. The SABRE people seem to have resolved those two issues, taking advantage of the harsh cryogenic cold of liquid hydrogen. Maybe such a thing really will work, we'll see. It operates as an airbreather from 0 to Mach 5 at around 100,000 feet, then switches to rocket using the oxygen stored aboard as it climbed.

That kind of lifting flight path to orbit is a very narrow corridor of speed vs altitude, above which the density is too low to permit lift equal to weight, and below which there are no known materials that can survive the aero-heating other than some rather heavy metals and ablatives. It's not exactly re-entry in reverse, but folks do tend to think of it that way. The problem is time: during entry most of your time is spent at near-orbital speeds, so the exposure is short. For flying into orbit, most of your time is at a modest supersonic speed, so the exposure is long. The transient heat-sinking we use for re-entry won't work for flying to orbit with some sort of hypersonic airplane, because of the long exposure times.

I have a problem regarding the specific Skylon airframe configuration with those tip-mounted engine nacelles. With parallel nacelles like that, you need to be essentially in vacuum before exceeding the low hypersonic speed range of Mach 5 to 7. Skylon's ascent may actually comply with that, if they can execute the pull-up once in rocket.

But for entry, they hit denser atmosphere at much higher speeds, nearer orbital. The conical shocks shed by the engine inlet spikes will impinge upon the leading edges of the wings. And we have known since the X-15A-2 flights that hypersonic shock impingements amplify the localized heating rates at the impingement points by factors on the order of 10. Those shocks will cut the wings off in mere seconds. There are no materials, ablatives, or anything known, that can survive that kind of heating.

The X-15A-2 would have lost its tail section given just a few more seconds of shock-impingement at Mach 6.7, 100 kft flight. It had a scramjet test article mounted to its ventral fin stub. The spike shock hit the ventral fin stub near its root, and damaged it and the underside of the tail, quite severely. Without that test article, nothing like that would have occurred, and did not occur, on other flights faster than Mach 5.

There is a reason that no entry spacecraft of any kind has ever had any sort of parallel nacelles that could shed impinging shock waves back and forth between nacelles. And I just told you exactly why that is. Skylon has to get rid of the tip-mounted engines, or it cannot survive entry. Simple as that.

GW

Last edited by GW Johnson (2024-03-26 09:15:06)

GW Johnson

McGregor, Texas

"There is nothing as expensive as a dead crew, especially one dead from a bad management decision"

Offline

#1784 2024-03-26 21:49:41

Re: Starship is Go...

Stainless steel never approaches the tensile strength of carbon fiber, regardless of temperature. I keep hearing this nonsense spouted off as if it were a fact. It is objectively and provably false.

…

Toray standard modulus carbon fiber yields / fails at 415ksi. Their T700 high modulus carbon fiber yields / fails at 710ksi. T800 yields / fails around 852ksi. Some of the strongest steels available, none of which are suitable for cryogenic temperatures, yield between 350ksi and 400ksi. There is no metal alloy that I'm aware of that yields at 700ksi. I'm just shy of absolutely certain that no metal alloys yield at 852ksi, and any that did would be unsuitable for propellant tanks subjected to both tensile and compression loads, never mind cryogenic temperatures.

You are correct that carbon fiber itself is stronger than steel. The problem is to form it into propellant tanks the individual fibers have to be epoxied together. It’s the epoxy, i.e., glue, which makes the structure weaker than the individual fibers. Carbon fiber tanks are more accurately called carbon-fiber composite tanks because they are a composite material containing the carbon fiber and the epoxy. Look up strengths of carbon fiber composite tanks.

Bob Clark

Last edited by RGClark (2024-03-26 21:51:36)

Old Space rule of acquisition (with a nod to Star Trek - the Next Generation):

“Anything worth doing is worth doing for a billion dollars.”

Offline

#1785 2024-03-26 22:08:17

Re: Starship is Go...

Marcus House speculates in response to a question from one of his viewers that the reason the SH/SS just barely made orbit on IFT-3 when it had 0 payload that perhaps it was only partially fueled. See at the 5:18 point here:

SpaceX's Frantic Push to Launch the Next Starship Mission is Nuts!

https://youtu.be/1HAcza0nE34

But actually SpaceX prior to the IFT-3 launch said SH/SS was fully fueled:

SpaceX @SpaceX

Propellant loading complete. Starship is fully loaded with more than 4500 metric tons (or 10 million pounds) of propellant

9:22 AM · Mar 14, 2024

https://twitter.com/SpaceX/status/1768266565085266349

Then the question remains: when payload capability is supposed to be 100-150 tons, why does a fully fueled SuperHeavy/Starship just barely make orbit(actually slightly less) carrying no payload, fully expending its propellant?

Think of it this way, what SpaceX demonstrated with IFT-3 was a launcher with a payload to LEO capability of 0 tons even when fully fueled and fully expending its propellant. Then how can it do Artemis Starship HLS refuelings when it gets 0 tons to LEO?

Bob Clark

Old Space rule of acquisition (with a nod to Star Trek - the Next Generation):

“Anything worth doing is worth doing for a billion dollars.”

Offline

#1786 2024-03-26 22:23:59

Re: Starship is Go...

SpaceX said they performed a “full duration” static fire of the Starship:

SpaceX @SpaceX

Full-duration static fire of all six Raptor engines on Flight 4 Starship

https://x.com/SpaceX/status/1772372482214801754?s=20

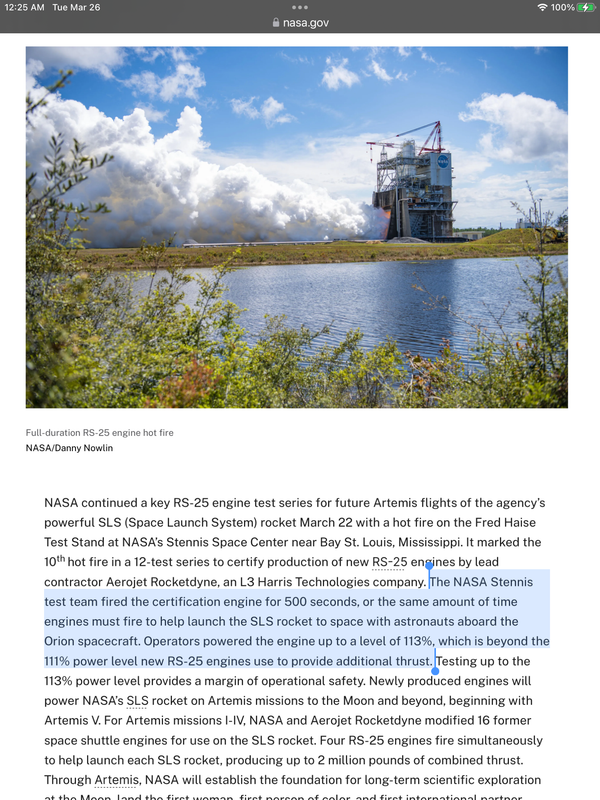

Sorry, but no. A 10-second burn is not full duration. THIS is full duration:

Another irritation of mine is that SpaceX won’t tell you what power level their tests are operating at. 50%?, 75%?, 100%? Usually, the launch company tells you this in their tests to confirm to potential customers their engines can operate at the needed power levels to complete their missions.

Robert Clark

Old Space rule of acquisition (with a nod to Star Trek - the Next Generation):

“Anything worth doing is worth doing for a billion dollars.”

Offline

#1787 2024-03-27 01:04:26

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 7,857

Re: Starship is Go...

Dr Clark,

You are correct that carbon fiber itself is stronger than steel. The problem is to form it into propellant tanks the individual fibers have to be epoxied together. It’s the epoxy, i.e., glue, which makes the structure weaker than the individual fibers. Carbon fiber tanks are more accurately called carbon-fiber composite tanks because they are a composite material containing the carbon fiber and the epoxy. Look up strengths of carbon fiber composite tanks.

A 700 bar CFRP compressed gas tank, which is made from both Carbon Fiber and resin (plastic), is stronger, stiffer, and lighter than a 350 bar steel tank of equal volumetric capacity. For equal H2 storage capacity and pressure, a steel tank will be 4X to 6X heavier than CFRP.

For CFRP to be 4X lighter than steel while containing the same pressure, it must be 4X stronger than steel for a given weight, else it would fail immediately. 850ksi high modulus T800 fiber corresponds with 212.5ksi steel. That is very strong steel- stronger than any cryogenic capable steel alloy's yield strength- by a lot. There are no austenitic stainless steel alloys that approach 212.5ksi yield strength, even at cryogenic temperatures.

There's your source:

Composites in Hydrogen Storage

If your assertion was even partially true, there would be at least one example of a steel high pressure compressed gas cylinder, made from any ferrous alloy that exists, that was at least comparable in terms of weight to similar CFRP tanks. There is not, because there are none. CFRP is stronger than steel, from absolute zero up to about 200F or so.

Offline

#1788 2024-03-27 06:16:58

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 19,421

Re: Starship is Go...

For RGClark re #1785

My understanding is that the flight plan was NOT intended to reach orbit.

Instead, it has been announced for months that the plan was to drop the second stage in the ocean.

The question that might be useful to know, if there is any way of finding the data, is how much mass was left in the Starship tanks at engine cutoff.

The answer to the question you posed (about delivery capability) might derive from that knowledge.

It will take some research to find the answer, and it may not be published or available indirectly, but I'm hoping you have the energy and the interest to see if you can find the answer and post it here.

(th)

Offline

#1789 2024-03-27 06:28:13

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 19,421

Re: Starship is Go...

For RGClark re #1784

The information you posted would surely have been true in 1930.

Sometime between 1930 and 2024, it appears (from reports by kbd512) that the information become false.

I am hoping you still have the energy and the interest to update your knowledge in this field, and then share what you learned with the forum.

Humans across the planet are constantly pushing at the envelope of what is possible, and most of us have no idea what is happening in labs and manufacturing facilities around the world.

(th)

Offline

#1790 2024-03-27 06:30:54

- GW Johnson

- Member

- From: McGregor, Texas USA

- Registered: 2011-12-04

- Posts: 5,801

- Website

Re: Starship is Go...

The trajectory was definitely suborbital, because if it were a surface-grazing ellipse, its apogee would have been halfway around the world over the Indian or Pacific Ocean somewhere. Its apogee was much closer, with the entry interface altitude hit on the descent, somewhere over the Indian Ocean. And that was apparently by design.

They did something for a "fuel transfer" test. I do not know what they did, but they pumped some quantity of propellant "somewhere", perhaps just overboard. I do not know how they handled the ullage problem in free fall! But if that test were "successful", then they are "doing something" about ullage. But that transfer would or could complicate the answer to any question about fuel quantities on board at an time during the mission.

There is no guarantee the Starship tanks were fully filled in the first place! A partially-filled lighter Starship would not require as much thrust from Superheavy to achieve adequate ascent kinematic performance. That affects the answer to the throttle-back question. The engines might have been at lower thrust setting, because that's all they thought they needed. It might or might not relate to any high-pressure leak troubles with Raptors. Hard to say.

SpaceX is close-mouthed about such details. They used to report engine performance on their site. They do not do that anymore, probably to prevent people like us from reverse-engineering more details of what they do. Such is typical when only the good things are released to the public.

GW

Last edited by GW Johnson (2024-03-27 06:35:34)

GW Johnson

McGregor, Texas

"There is nothing as expensive as a dead crew, especially one dead from a bad management decision"

Offline

#1791 2024-03-29 01:57:51

Re: Starship is Go...

Elon Musk @elonmusk

Getting ready for Flight 4 of Starship!

Goal of this mission is for Starship to get through max reentry heating with all systems functioning.

https://x.com/elonmusk/status/1773085211275698302?s=20

How about showing it can get anywhere near the 150 tons payload to LEO claimed?

What IFT-3 showed was a launcher with 0 tons to LEO payload capability, even when fully fueled and fully expending its propellant. Then how can it do Artemis Starship HLS refuelings when it gets 0 tons to LEO?

Bob Clark

Old Space rule of acquisition (with a nod to Star Trek - the Next Generation):

“Anything worth doing is worth doing for a billion dollars.”

Offline

#1792 2024-03-29 09:22:49

Re: Starship is Go...

For RGClark re #1785

My understanding is that the flight plan was NOT intended to reach orbit.

Instead, it has been announced for months that the plan was to drop the second stage in the ocean.

The question that might be useful to know, if there is any way of finding the data, is how much mass was left in the Starship tanks at engine cutoff.

The answer to the question you posed (about delivery capability) might derive from that knowledge.

It will take some research to find the answer, and it may not be published or available indirectly, but I'm hoping you have the energy and the interest to see if you can find the answer and post it here.

(th)

Yes, the planned trajectory was to be just short of orbit. But that speaks even worse for SpaceX because it means IFT-3 demonstrated a vehicle with negative payload to orbit capability even though fully fueled and fully expending propellant.

You can see the propellant load of both stages in the graphics overlain by SpaceX on the launch video, showing the both stages virtually fully loaded with propellant on launch and virtually fully expended on engine shutdown:

FULL FLIGHT! SpaceX Starship IFT-3.

https://youtu.be/W1WfCVZFZPo

Bob Clark

Old Space rule of acquisition (with a nod to Star Trek - the Next Generation):

“Anything worth doing is worth doing for a billion dollars.”

Offline

#1793 2024-03-29 11:14:40

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 7,857

Re: Starship is Go...

How do we know that SpaceX did not throttle the engines in such a way as to account for not having any payload aboard?

I think you have to do that to some degree, in order to remain within airframe structural limits. Any throttling of the engines makes them less fuel efficient than they are at maximum thrust, same as with any other gas turbine based engine technology. You burn a lot more fuel at lower power settings, relative to the thrust being generated, but that is not the same as not having thrust available. That doesn't automatically mean an unladen Starship struggles to achieve orbit, merely that running the engines at lower thrust than nominal, happens to be a great way to "burn" a full propellant load without achieving maximum possible thrust. They're shoving all the propellant mass through the engines, proving that all the mass will go through the engines without the engines exploding. If you don't throttle up all the way, then in the same way that a low-bypass turbofan or turbojet eats fuel like mad at idle power, while producing negligible thrust, I'd imagine that a rocket could be run in a similarly inefficient manner. The upside is that this avoids bending things on a very lightly loaded upper stage. This thrust manipulation is done with virtually all liquid fueled rockets to maintain acceleration rates and avoid over-stressing the airframe, so I see no reason why Starship cannot do the same thing.

Offline

#1794 2024-03-30 00:03:48

Re: Starship is Go...

How do we know that SpaceX did not throttle the engines in such a way as to account for not having any payload aboard?

I think you have to do that to some degree, in order to remain within airframe structural limits. Any throttling of the engines makes them less fuel efficient than they are at maximum thrust, same as with any other gas turbine based engine technology. You burn a lot more fuel at lower power settings, relative to the thrust being generated, but that is not the same as not having thrust available. That doesn't automatically mean an unladen Starship struggles to achieve orbit, merely that running the engines at lower thrust than nominal, happens to be a great way to "burn" a full propellant load without achieving maximum possible thrust. They're shoving all the propellant mass through the engines, proving that all the mass will go through the engines without the engines exploding. If you don't throttle up all the way, then in the same way that a low-bypass turbofan or turbojet eats fuel like mad at idle power, while producing negligible thrust, I'd imagine that a rocket could be run in a similarly inefficient manner. The upside is that this avoids bending things on a very lightly loaded upper stage. This thrust manipulation is done with virtually all liquid fueled rockets to maintain acceleration rates and avoid over-stressing the airframe, so I see no reason why Starship cannot do the same thing.

Perhaps, GW can address this but I can only think of three ways a rocket in general can launch a smaller payload than what its max payload capability is. Note, usually a rocket carries much less payload than it’s max capability. For instance the Falcon 9 has 22.8 ton max payload to orbit but it never launches that much.

One way is to partially fuel the rocket, another way is to cut the stage burns early, a third way is to throttle down the engines. This video shows essentially full propellant loads at launch for both stages and essentially full propellant depletion at stage shut down:

FULL FLIGHT! SpaceX Starship IFT-3.

https://youtu.be/W1WfCVZFZPo

If the burns were shut down early then you would have more left over propellant. That didn’t happen. So the third way is to throttle down the engines. I have speculated that SpaceX has done this:

Did SpaceX throttle down the booster engines on the IFT-2 test launch to prevent engine failures?

http://exoscientist.blogspot.com/2023/1 … oster.html

The problem is SpaceX won’t admit it has done this. This is an important point because my argument is that SpaceX throttles down the engines to increase engine reliability, and SpaceX won’t admit there is still a problem with engine reliability.

If SpaceX is throttling down the engines just because of smaller payload, why not just admit that? Why this pretense of running the engines at full power?

Bob Clark

Last edited by RGClark (2024-03-30 00:33:20)

Old Space rule of acquisition (with a nod to Star Trek - the Next Generation):

“Anything worth doing is worth doing for a billion dollars.”

Offline

#1795 2024-03-30 11:33:44

- GW Johnson

- Member

- From: McGregor, Texas USA

- Registered: 2011-12-04

- Posts: 5,801

- Website

Re: Starship is Go...

Bob may be right, they may still be having troubles operating Raptor-2 engines near full power. They wouldn't be the first to face that. Even the F-1's on the old Saturn-5 had similar teething troubles early on. The uprate from 1.5 M lb thrust to 1.8 M lb thrust came much later than Apollo 11.

That being said, you don't bite off the full amount the first time you try to chew. They got to something resembling orbital flight, in a very long suborbital trajectory. They did it with some excess propellant aboard that they could move around in a first-time free-fall test of propellant transfer (even if it was simply pumped overboard, nobody has said).

I rather doubt the Starship upper stage had a full propellant load aboard, especially since it carried no cargo (the decks and structures for that not being included in the test vehicle). That greatly lightens the payload for the Superheavy first stage, allowing it to not only operate with less than a full propellant load, but also to require less thrust at launch to achieve the goal of about T/W ~ 1.5 for good kinematics. That lets them operate at less than full thrust, should all 33 engines operate, and they did.

All in all, that's a well-thought-out first orbital-resembling test plan. And it gives them some more full-burn time experiences with these Raptor-2 engines.

There is a Raptor-3 in work, you know!

It's far too early to be demanding full-capability demonstrations in this test program. Let them work up to it.

GW

GW Johnson

McGregor, Texas

"There is nothing as expensive as a dead crew, especially one dead from a bad management decision"

Offline

#1796 2024-03-30 13:12:22

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 29,433

Re: Starship is Go...

That would give them data on the payload rise timing to adjusting of engine thrust curve. Since the payload on the bfr is a full starship. Next would-be making use of the starships data to get equally variable data forgetting to orbit controlled as well for altitude.

Saw a video link on utube for the last launch and that for the upcoming IFT-4 seems to have indicated that the launch pad was damaged along with damage from engines on the starship during its firing.

Offline

#1797 2024-04-01 23:24:49

Re: Starship is Go...

So what changes did SpaceX make to insure Starship didn’t reach orbit when Elon said before the flight it had a 80% chance of reaching orbit?

“Starship Flight 3 Update - Probability of Reaching Orbit 80%” said Elon Musk.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lCe8a7XcG8o

Oddly, not only did he say before the flight Starship had an 80% chance of reaching orbit, he even said on Twitter after the flight it did reach orbit:

Elon Musk @elonmusk

Starship reached orbital velocity!

Congratulations @SpaceX team!!

9:40 AM · Mar 14, 2024 45.5M Views

6.9K 16K 209K 1.6K

https://twitter.com/elonmusk/status/1768271078999167379

An odd thing for the Chief Engineer of SpaceX to say. This tweet from Elon received 45 million views. Apparently, it led many news sources to repeat the claim Starship reached orbit on IFT-3:

RESEARCH

Payload Research: Tracking Starship’s Progress with Additional Flights on the Horizon

By Jack Kuhr

March 20, 2024

Starship reached orbital velocity during IFT-3 last week, largely validating its capability as an expendable rocket while SpaceX continues to try to nail down vehicle recovery.

https://payloadspace.com/payload-resear … iguration/

Bob Clark

Old Space rule of acquisition (with a nod to Star Trek - the Next Generation):

“Anything worth doing is worth doing for a billion dollars.”

Offline

#1798 2024-04-02 09:05:28

- GW Johnson

- Member

- From: McGregor, Texas USA

- Registered: 2011-12-04

- Posts: 5,801

- Website

Re: Starship is Go...

Two comments:

1. It did reach orbit. It just was an elliptical orbit that intersected the atmosphere or the surface near its perigee end. That's not what most people consider to be an "orbit", yet it is one. Every suborbital ICBM or probe rocket follows a similar path, just with (usually) a higher apogee. The theoretical perigee can be way inside the planet mathematically. The 2-D Cartesian small-scale approximation to this is the parabolic ballistic path, an inappropriate approximation at large scale (comparable to planet radius). But the real situation is 3-D spherical, and any path at max (perigee) speeds under escape is always elliptical mathematically.

2. Elon Musk is listed as "chief engineer" of SpaceX in violation of the Texas engineering practice act (money obviously talks!). He is not registered with Texas or any other state as an engineer, and in fact does not have an engineering degree of any kind! He cannot legally sign any drawings in the State of Texas for SpaceX, only a registered professional engineer can do that. Somebody else employed by SpaceX who is registered as an engineer in one of the 50 states must do that drawing signoff.

GW

Last edited by GW Johnson (2024-04-02 09:08:08)

GW Johnson

McGregor, Texas

"There is nothing as expensive as a dead crew, especially one dead from a bad management decision"

Offline

#1799 2024-04-03 02:03:24

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 7,857

Re: Starship is Go...

I found a chart which speaks to Dr Clark's point about a composite being overall weaker than the fiber alone, but it further reinforces my point about the yield strength of CFRP composites as compared to any kind of steel. A composite being weaker than the fiber used therein, is objectively true for all fiber-based composites, but misses the broader point that a composite remains both stronger and stiffer than any kind of steel for equivalent weight, from deeply cryogenic temperatures to about 200F. That is why composites are so pervasively used in aerospace vehicle structures, in rocketry as well as commercial or military aircraft.

The fiber in this case is 4,900MPa / 710,500psi capable (T700), but the overall composite's yield strength is 2,550MPa / 369,750psi.

The yield strength (YS) of C350 maraging steel (a high alloy Nickel-Chromium "maraging" ("martensitic aging") steel, is 350,000psi. C350 does have comparable YS to CFRP, but Charpy V-notch tests will illustrate why it's not used for cryogenic applications. Maraging steels were in fact tested by NASA for cryogenic service, but their ductility remains lower than austenitic stainless steels. This is unsurprising, because C350 has a martensitic grain structure. It's very hard and very strong, but not as ductile as 304L stainless, despite similar alloy contents. Mangalloy does much better in the ductility department than C350. 304L at -320F / -196C has a tensile strength of 223,000psi, but as the link below shows, even 304 loses at least 22% of its room temperature ductility at LOX/LCH4 temperatures. Mangalloy does a little worse, C350 worse than that.

TYPES 304 AND 304L STAINLESS STEELS - Low Temperature Data Sheet

There has been some point made about the fracture toughness of polymer or epoxy at moderate cryogenic temperatures, which has some merit to it, but optimization of the epoxy and fiber materials used often indicates increased fracture toughness at cryogenic temperatures, as compared to room temperature, due to the intrinsic properties of polymers at low temperatures (until you arrive at LH2 temperatures, whereupon that statement appears to hold universally true, due to fundamental physics):

Properties of Cryogenic and Low Temperature Composite Materials

The properties of composite materials subjected to low and cryogenic temperatures have been reviewed. Generally, cold temperature has a positive effect on composites resulting in improved strength, modulus, fatigue and thermal properties. Contrarily, it causes a reduction in ductility, leading to lowered failure strain, fracture toughness and impact resistance.

There is also some truth to the fact that lower tensile strength fiber performs better at cryogenic temperatures, and thus the use of high modulus fiber may lead to worse overall service life, as compared to stainless steel, but this is not universally the case. What does become important for CFRP at cryogenic temperatures are stress and strain rates (rapid heating or cooling are problematic), so this could very well be one area where there is an intrinsic technical issue with the use of composites at cryogenic service temperatures.

If I had to hazard a guess, Elon Musk (most likely) or someone else at SpaceX attempted to apply their observations about what happens to highly stressed COPVs at cryogenic temperatures to a CFRP main propellant tank that experiences nowhere near the stress of a CFRP COPV operated at the same temperature.

Offline

#1800 2024-04-03 09:21:52

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 7,857

Re: Starship is Go...

On advice from tahanson43206...

COPV is a term that means "Carbon Fiber Reinforced Plastic Overwrapped Pressure Vessel". A COPV could have a plastic or metallic liner, with plies of unidirectional Carbon Fiber tape or fabric wrapped over the liner, in order to provide the lightest yet strongest structural reinforcement to contend with the hoop stress applied to the wall of the pressure vessel by its highly pressurized gas contents. They're normally / almost universally spherical in shape, which happens to be the best shape to use for uniformity of stress concentration applied to the inner walls by the highly pressurized gases contained within them. In other words, a spherical shape does the absolute best job of maximizing internal volume while minimizing asymmetric stress concentrations, and therefore means a spherical pressure vessel will be the lightest possible for a given internal volume and pressure applied within by highly pressurized gas.

You will never see a rectangular COPV, for example, because while a rectangle may be able to fit into some specific part of a rocket better than a sphere, meaning greater utilization of available interior space, there will be a wild increase in the stress concentration applied to the edges of a rectangular pressure vessel, to the point that failure is extremely likely unless the weight of the reinforcement material is increased to some absurd degree. Since one of the overriding design goals in rocketry is to make each component as light as it can be while still surviving all the forces it will be subjected to, a rectangular COPV is a non-starter. For various safety reasons, it's a non-starter in non-rocket applications as well. ASME Boiler Pressure Vessel code / standards (aka, "The Bible") defining what an engineer may or may not do, would either implicitly or expressly forbid such a design. Knowingly designing something that runs directly counter to accepted engineering practices would be grounds for having your license as engineer rescinded, with good cause. That Titan CFRP submarine pressure hull implosion is a good example of an unacceptable engineering practice that the owner of the company was repeatedly warned not to use by other highly competent mechanical engineers. Ego and belief, without true understanding and acceptance of real wisdom, proved to be a fatal combination. He didn't listen, so now he's dead, along with all of his passengers- needlessly crushed to death so fast that their brains couldn't process their final moments amongst the realm of the living. ASME Boiler Pressure Vessel Code was written in blood. Every engineering practice outlined within it is squarely directed at future avoidance of catastrophic structural failures, and the associated loss of life or property, which tends to lead to circular solutions in pressure vessel design ![]() . That's an engineering joke, but it's also engineering reality. As with all other aspects of engineering, there are good reasons why things are done in specific ways. The effect of geometry and materials selection on the stress concentration is one of the engineering design considerations applied to COPVs. It's not random, it's not to confuse curious onlookers, and it's not "just because".

. That's an engineering joke, but it's also engineering reality. As with all other aspects of engineering, there are good reasons why things are done in specific ways. The effect of geometry and materials selection on the stress concentration is one of the engineering design considerations applied to COPVs. It's not random, it's not to confuse curious onlookers, and it's not "just because".

When you learn enough about how and why something works, you don't attempt random things and hope for a good result. The use of full-flow staged combustion engines for Starship wasn't random or because Elon Musk thought it would be cool to try. The real aerospace engineers who took his cocktail napkin sketch and transformed it into a working super heavy lift launch vehicle understood that the performance he wanted demanded the use of that engine cycle, so that's what they designed to meet his performance demands. LOX and LCH4 were used because they could provide autogenous / "self" propellant tank pressurization without having any heavy COPVs onboard, and they had very similar temperatures in their liquid states, so both cryogenic propellants were thermally compatible without the need for a heavily insulated wall between the oxidizer and fuel tanks.

COPVs are highly stressed / highly loaded pressure vessels that store inert gases used to pressurize the main propellant tanks, typically Helium or Nitrogen compressed to at least several hundred atmospheres of pressure. A 350 bar tank, for example, contains Helium at 5,145psi. If high modulus fiber such as TorayCA T700 is used in these pressure vessels, matching the CTE (Coefficient of Thermal Expansion) of the epoxy resin to the CTE of the Carbon Fiber becomes critically important to prevent the formation or expansion of microcracks in the resin matrix at cryogenic temperatures, because the epoxy resin is binding the Carbon Fiber together. It should be obvious what will happen if this is not done, but the less technical version of the problem is that the fiber will actually "pull away from" the resin matrix binding or "gluing" it together, if there's a CTE mismatch. These days, we have resins and high modulus fibers with well-matched CTEs. That was not always the case.

An example of CTE mismatch in metals would be a steel stud screwed into an Aluminum engine block or cylinder head. After thermal cycling, aka "running the engine", removing said stud can be very problematic. Steel exhaust studs, stainless or otherwise, are notorious for getting sheared off in Aluminum cylinder heads upon attempted removal, for example.

It should also be noted that there's quite a bit that you can "get away with", in terms of weight reduction, for single-use structures like pressure vessels, that rapidly become serious engineering issues with multiple reuses.

Due to the proximity of COPVs to the cryogenic main propellant tanks, they will typically be exposed to cryogenic temperatures during flight, which means they have to deal with both deeply cryogenic and potentially elevated temperatures from aerodynamic heating of the vehicle, which occurs during hypersonic ascent and potentially reentry speeds as well, if the vehicle is reusable.

If I threw out any other terms without defining or explaining them, or why they're noteworthy, please let me know.

Offline