New Mars Forums

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

Announcement

#26 2019-04-03 18:46:10

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 29,933

Re: Mars Co2 or other compressed Gas Hopper rocket

I got a website timeout error as well for the next link as well.

http://ssl.mit.edu/files/website/theses … lSarah.pdf

Offline

Like button can go here

#27 2019-04-03 18:58:09

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 23,516

Re: Mars Co2 or other compressed Gas Hopper rocket

For SpaceNut ... thanks again for the link you provided to another site, which I followed to a live feed to Sarah's paper:

https://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/67069

The paper (from 2011) is (apparently) downloadable as a pdf.

Edit 2019/04/04:

Publisher: Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Date Issued: 2011

Abstract:

The TALARIS (Terrestrial Artificial Lunar And Reduced gravIty Simulator) hopper is a small prototype flying vehicle developed as an Earth-based testbed for guidance, navigation, and control algorithms that will be used for robotic exploration of lunar and other planetary surfaces. It has two propulsion systems: (1) a system of four electric ducted fans to offset a fraction of Earth's gravity (e.g. 5/6 for lunar simulations), and (2) a cold gas propulsion system which uses compressed nitrogen propellant to provide impulsive rocket propulsion, flying in an environment dynamically similar to that of the Moon or other target body. This thesis focuses on the second of these propulsion systems. It details the practical development of the cold gas spacecraft emulator (CGSE) system, including initial conception, requirements definition, computer design and analysis methods, and component selection and evaluation. System construction and testing are also covered, as are design modifications resulting from these activities. Details of the system's integration into the broader TALARIS project are also presented. Finally, ongoing and future work as well as lessons learned from the development of the CGSE are briefly discussed.

Notes after scanning first 32 pages .... this paper covers work done at MIT and Draper labs over several years. The inspiration appears to have been the Google Lunar X Prize competition. The author provides plenty of history of prior work, including NASA development of cold and warm gas thrusters. The limitations of cold gas as a propellant are identified early, so I'm looking forward to finding out if the 500 meter range called for in the competition was achieved.

I note that 500 meters is not a kilometer, so it does not follow (Louis!) that if 500 meters was achieved, a full kilometer can be.

(th)

Last edited by tahanson43206 (2019-04-04 11:41:45)

Offline

Like button can go here

#28 2019-04-03 19:26:03

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 29,933

Re: Mars Co2 or other compressed Gas Hopper rocket

Thanks as well for the digging.

At the bottom of that page is also another link to open the full documents 128 pages.

I see from the abstract that they used nitrogen which would be comparible to the mars co2 use for the thruster.

They also used four electric ducted fans to offset a fraction of Earth's gravity (e.g. 5/6 for lunar simulations) which would be a different ratio for mars. I suggested helium gas to get a simular bouyancy effect as fans would not be all that useful on mars. This would allow for a full design creation which can be tested.

Offline

Like button can go here

#29 2019-04-04 11:15:00

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 23,516

Re: Mars Co2 or other compressed Gas Hopper rocket

For SpaceNut re #28 ...

The offset of gravity, used for the NASA helicopter tests, and for Ms. Nothnagel's paper, would not be needed on Mars.

Mars provides its own offset (in a way of speaking). For that reason, I think a supply of helium would not be needed.

However, for testing ** ON EARTH **, I like the idea, simply because it would appear to be a lot less complicated than the set of four fans used in Ms. Nothnagel's work.

On the OTHER hand, if the drone can be made to lift itself on Earth, then we are guaranteed a payload capacity equal to or greater than the mass of the drone itself. For that reason, I would like to see development and testing proceed without gravity modification.

Hopefully, Ms. Nothnagel's paper will answer questions I have now, about the amount of thrust she was able to achieve per nozzle, and the mass of the gas container and other hardware needed to control the flow of gas.

In another paper you found recently, I noted that while the purpose of the study was satellite positioning in orbit, the authors reported achieving a low ISP in the range of 70. I'll be interested to learn what ISP was achieved by the MIT team.

I'd like to refer back to a note you posted recently, to the effect that the gas in a cold gas thruster vehicle could be heated to increase pressure in the pressure vessel, and thus increase potential thrust from the nozzle

And that observation brings me full circle, to your suggestion of RF energy supply to a flying vehicle. While solar panels would be useful only at selected times of each Sol, an RF energy transfer system would be useful 24 hours per Sol, and particularly useful during inclement weather.

Furthermore, the proposed design of the vehicle would NOT depend upon mechanical components exposed to the atmosphere of Mars, and thus would NOT be subject to failure of bearings (for example) due to grit in the atmosphere.

Thus, while the design specification offered initially is for a range of 1 kilometer and return, use of RF energy supply could permit the vehicle to travel further if the supply of propellant is sufficient to permit longer flights.

My hope is that qualified readers of this topic will decide to participate as co-designers of an open-source cold gas drone for deployment on Mars.

Application for membership in NewMars forum appears to be (relatively unobstructed), but potential members should know that quirks do occur upon occasion. If you apply for membership, and you do not receive the email from the forum containing a starting password, it would be a good idea to look in your spam filter.

If you apply for membership and do not receive the first password email for some other reason, there is a contact capability in the login form. You may have to request assistance more than once. The support staff is all volunteer (as I understand it) and NewMars forum is just one of many responsibilities they are supporting.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#30 2019-04-04 17:56:38

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 29,933

Re: Mars Co2 or other compressed Gas Hopper rocket

The other part of the balloon concept is to lift it to mars level of atmosphere to be able to test inflight area that corresponds to mars.

So the real thing is what are we doing for a design for mars a clean slate or a salvage operation reuse as that will dictate lots for what we can expect to achieve.

As for the RF power and such, I posted in the helo topic for mars.

Offline

Like button can go here

#31 2019-04-05 20:53:50

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 23,516

Re: Mars Co2 or other compressed Gas Hopper rocket

Report on Nothnagel paper, through page 47 ...

For SpaceNut ... thanks again for the link you provided to another site, which I followed to a live feed to Sarah's paper:

https://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/67069

The paper (from 2011) is (apparently) downloadable as a pdf.

Notes after scanning first 32 pages .... this paper covers work done at MIT and Draper labs over several years. The inspiration appears to have been the Google Lunar X Prize competition. The author provides plenty of history of prior work, including NASA development of cold and warm gas thrusters. The limitations of cold gas as a propellant are identified early, so I'm looking forward to finding out if the 500 meter range called for in the competition was achieved.

I note that 500 meters is not a kilometer, so it does not follow (Louis!) that if 500 meters was achieved, a full kilometer can be.

(th)

In the pages between 32 and 47, the author describes design considerations which led to selection of cold gas thrusters for the student project.

The distance to be covered by the constant thrust hopper was 30 meters, and as of page 47 that was considered ambitious. The propellant envisioned for the actual 500 meter Google Lunar X Prize vehicle was monopropellant, due to its greater ISP and other factors. Cold gas was chosen for the student project due to safety considerations, and because a cold gas system could permit exercise of all of the control systems that would be needed for the hot gas vehicle.

For Louis .... at this point, it is looking less and less likely that a cold gas thruster system would be capable of meeting the design objectives for the pizza delivery drone on Mars (or anywhere).

However, I will continue reviewing the paper to see how things turned out.

It is worth noting that Carbon Dioxide was considered for the cold gas thruster, in part because there is considerable experience with it in practice. However, that experience led to recognition that Nitrogen would be a better choice for the student project. Since this topic is focused upon use of Carbon Dioxide at Mars, I was interested in the discussion of the pros and cons of use of that gas. In particular, I was surprised to learn that in the proposed configuration, Carbon Dioxide would exist in both a liquid phase and a gaseous phase in the pressure vessel, and this would complicate operation, since the gas phase would be needed for thrust.

Edit: Upon reflection, I should not have been surprised, since that very phenomenon was cited in the reference cited previously, about use of Carbon Dioxide for paint ball propulsion. A challenge for paint ball competitors using Carbon Dioxide was to keep liquid from gumming up the firing mechanism, by insuring that the weapon was held so that liquid was below gas in the firing subsystem.

(th)

Last edited by tahanson43206 (2019-04-05 20:59:13)

Offline

Like button can go here

#32 2019-04-05 21:12:40

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 29,933

Re: Mars Co2 or other compressed Gas Hopper rocket

The " monopropellant" would most likely be hydrogen peroxide.

The single fuel approach means a large pulse of heating must occur with Co2 to give it more punch going from compressed liquid or near it to vapor as it exits the engine nozzle.

There is still merit to making small hoppers for specific use; it will take time and investigation as to what makes the most sense.

Offline

Like button can go here

#33 2019-04-07 07:26:50

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 23,516

Re: Mars Co2 or other compressed Gas Hopper rocket

This post is intended to report on pages 48-85 of the MIT paper on cold gas thrusters for a hopper design for the Google Lunar X Prize competition.

Before proceeding, I would like to offer a word of appreciation for the ecosystem of the NewMars forum, with particular emphasis on the important contributions of Louis. Because of Louis' (apparently naive) expression of optimistic hope that a cold gas hopper could work on Mars, SpaceNut used his (remarkable to me) search skills to come up with links that eventually led to the MIT study. And because of Louis' inspiration, I've been following the progress of the students over several years, as they dealt with the realities of the Universe we live in. The author of the paper (Nothnagel) has done (what I perceive to be) an outstanding job of describing complex mathematical and engineering challenges in a way that is (relatively) easy for me to follow.

As I closed page 85 yesterday evening, I had come to understand some of the tradeoffs the students had to make, to achieve their objective, of a demonstration of a hopper that could work on the Moon, using Nitrogen gas for safety, but ONLY for 30 meters and ONLY for 15 seconds of powered flight.

At this point, I still don't know how the work is going to turn out, but I DO have a sense of how the students used MATLAB (for example) to predict the operating conditions which the components they were going to select were going to participate in.

This section of the paper opened with a detailed presentation of the mathematics involved in designing a hopper for the Moon or elsewhere. The discussion proceeded to component selection, which included evaluation of promised performance, mass and cost. For example, space rated components met all design objectives for performance, but cost thousands of dollars. In the end, the students found components that (just barely) met performance requirements and were affordable for the available budget.

In the closing portion of today's reading, the students reported results of laboratory tests of the chosen components, which confirmed that they would meet requirements in practice, so the work could proceed to building the complete hopper.

Edit: Following the lead that performance of a cold gas thruster can be enhanced by heating the gas before it reaches the nozzle, I found a draft entry on Wikipedia:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Resistojet_rocket

The Wikipedia editors appear to be unhappy with this article, and I presume this means it will be improved over time. However, the big take-away for me was information that the technique has been used since 1965, and is in use today in satellite applications.

The key concept (for me) was that this technique works best where mass constraints are severe, but energy is available. In the context of the Mars hopper, and in light of the work reported by MIT students above, I am coming around to liking SpaceNut's suggestion of an RF feed to a Mars CO2 hopper more and more. The distinct advantage of a cold gas thruster design over a helicopter is the absence of mechanical components exposed to the atmosphere. All mechanical components of a hopper on Mars can be enclosed in a protective (light weight) aerodynamic shell.

The mass limitations that (apparently) beset all gas thruster designs may be overcome (to what extend I still don't know) by external supply of energy.

Note: In a Wikipedia article on cold gas thrusters, I found a citation that the maximum theoretical ISP of Nitrogen is 73, with the best ISP achieved in practice is 70.

SpaceNut reports 76 as the maximum, so I may have misread the 73.

(th)

Last edited by tahanson43206 (2019-04-07 08:02:22)

Offline

Like button can go here

#34 2019-04-07 07:56:45

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 29,933

Re: Mars Co2 or other compressed Gas Hopper rocket

Matlab is a visual GUI programing for testing program that can make use of the IEEE488 bus communications equipments.. Its been years since working with it, in fact decades....

Such praise as I am more of a janitor than a PHD in anything...but thanks.

Here is some more of that data mining... https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cold_gas_thruster

The maximum theoretical specific impulse for nitrogen gas is 76 seconds. In the simplest approximation, the specific impulse is modeled as proportional to the square root of the (absolute) gas temperature, so performance rises as the gas temperature is increased. A thruster in which the performance is increased by heating the gas by an electrical resistance is known as a resistojet.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thermal_rocket

cdn.intechopen.com/pdfs/37528/InTech-Cold_gas_propulsion_system_an_ideal_choice_for_remote_sensing_small_satellites.pdf

Cold Gas Propulsion System – An Ideal Choice for Remote Sensing Small Satellites

scholarworks.wmich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?filename=2&article=3407&context=honors_theses&type=additional

DESIGN AND ANALYSIS OF A COLD GAS PROPULSION SYSTEM FOR STABILIZATION AND MANEUVERABILITY OF A HIGH ALTITUDE RESEARCH BALLOON

Basic equation

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/4e80/3 … c5293c.pdf

Designing Space Cold Gas Propulsion System using Three Methods: Genetic Algorithms, Simulated Annealing and Particle Swarm

www.vacco.com/images/uploads/pdfs/cold_gas_thrusters.pdf

VACCO Cold Gas Thruster

https://bhushandarekar.com/wp-content/u … -13-56.pdf

Cold Gas Propulsion System for Hyperloop Pod

https://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi … 002697.pdf

NASA Marshall Space Flight Center, Tri-gas Thruster Performance Characterization

Offline

Like button can go here

#35 2019-04-07 20:14:28

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 23,516

Re: Mars Co2 or other compressed Gas Hopper rocket

Report on conclusion of MIT student paper on development of Nitrogen cold gas hopper test vehicle:

First, I'd like to point out the accuracy of SpaceNut's prediction, given below:

The " monopropellant" would most likely be hydrogen peroxide.

The single fuel approach means a large pulse of heating must occur with Co2 to give it more punch going from compressed liquid or near it to vapor as it exits the engine nozzle.

There is still merit to making small hoppers for specific use; it will take time and investigation as to what makes the most sense.

From conclusion of TALARIS paper (Nothnagel):

While there might be some performance gains to be made by upgrading the CGSE, they would likely be

relatively small, since cold gas is simply not a particularly efficient form of propulsion. To make any

significant improvements, particularly in terms of longer flight times, it would likely be necessary to

convert the TALARIS spacecraft emulator propulsion system from cold gas to an energetic propellant. As

discussed in section 2.3.2, the most likely candidate for this upgrade would be monopropellant

hydrogen peroxide. However, an upgrade of this scale would require a significant investment of time

and money, and development would have to proceed extremely carefully, due to the more extensive

hazards inherent in working with energetic propellants.

As of the time the paper (Nothnagel) was published, the test vehicle had not yet completed testing, and had not flown over the planned 30 meter test range.

The conclusion of the paper described the intensive, progressive testing carried out by the development team, including discovery of an unanticipated reduction in performance. One of the components required additional protection circuitry recommended by the manufacturer. This need had not been anticipated earlier, so the team had to study the problem, identify the negative interaction of the required safety circuitry, and find a work around.

In the end, the thrusters performed well above the MATLAB predicted performance, achieving over 50 Newtons of thrust compared to the expected 40.

Because the paper was dated 2011, I expect there may be follow up reporting to show how the hopper performed when unrestricted flight testing was performed, (assuming it actually DID reach that point).

However, the primary takeaway for me, from reading this well written paper, was an understanding of why Louis' original idea has not been achieved in the real world, on Earth or anywhere else. Cold gas propulsion has been useful in space since 1965, and it remains very useful today, including in SpaceX rockets, but I come away from this reading with a much better sense of why it has not been developed for vehicle application to date, and why it will (most likely) never be developed for that purpose, on any body which has a significant gravity.

Edit: However, SpaceNut's suggestion of using externally supplied power to heat the working fluid of a cold gas thruster vehicle before exit from the nozzle remains well worth study. The technology has been and remains in active use in satellite applications, and it may turn out to be a cost effective way of supporting use of cold gas drones for movement of small payloads on Mars. The problem to be solved arises from the low thrust attainable from unassisted cold gas thrusters. Thrust can be increased given externally supplied energy at flight time.

Having said that, unheated cold gas thrusters may prove ideal for getting about in the vicinity of ultra-low gravity sites, such as Phobos or any of a myriad of asteroids.

Thanks again to Louis, for providing the initial impetus to undertake this reading, and to SpaceNut for finding the links that led to this paper.

(th)

Last edited by tahanson43206 (2019-04-07 20:30:29)

Offline

Like button can go here

#36 2019-04-08 17:34:26

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 29,933

Re: Mars Co2 or other compressed Gas Hopper rocket

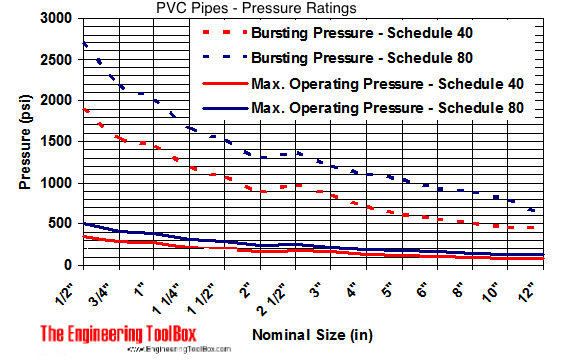

With all of the discussion of PVC, I began to wonder if it could be used in a 3D printer as semi liquid feed stock supply method which when heated by laser would set it up to form any shape that we would want. This could be a means to create composite tanks and other connection items rather than using metals. Create a thin shape then coat it with basalt fiber glass and then overlay another coat of pvc to finish it up. The tunnel lining for pipeline topic also could be a large storage tank as well for fuel for this hopper to make use of.

http://www.heritageplastics.com/pvc-wat … -dwv-pipe/

http://www.lascofittings.com/pressureratingsofplastics

Pressure Ratings of Thermoplastic Fittings

Offline

Like button can go here

#37 2019-04-08 18:18:53

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 23,516

Re: Mars Co2 or other compressed Gas Hopper rocket

For SpaceNut ...

Thanks for #36 ... interesting extension of PVC discussion into the hopper topic

***

Following the lead reported above, I am now investigating heated CO2 propulsion ...

Mr. Google came up with the paper at the link below:

https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/cgi/view … t=smallsat

This paper discusses the topic of heating CO2 in a tank to make it fully in gaseous phase, before it is allowed to escape to a regulator and on to an output nozzle.

The application is (apparently) limited to satellite positioning, but I'll go back to study it to see if there is any chance the technique could be adapted for the hopper. I am skeptical this technique would provide sufficient thrust to allow a hopper to complete the proposed 1 kilometer in 30 minutes delivery mission, but am definitely motivated to see if it would perform better than cold gas by itself, as described by the MIT student paper (Nothnagel).

(th)

Last edited by tahanson43206 (2019-04-08 18:20:07)

Offline

Like button can go here

#38 2019-04-08 19:07:39

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 29,933

Re: Mars Co2 or other compressed Gas Hopper rocket

pg 3 shows the heating

This is the satelite use

https://arc.aiaa.org/doi/pdf/10.2514/6.2014-3759

Cold Gas Propulsion System Conceptual Design for the SAMSON NanoSatellite

Offline

Like button can go here

#39 2019-04-08 21:39:42

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 23,516

Re: Mars Co2 or other compressed Gas Hopper rocket

For SpaceNut ... the paper on the carbon dioxide thermal rocket looks like exactly what I was hoping for as a next stage to study.

The researchers appear to have built a working prototype, and the distance covered may be as much as a 100 meters.

There is a graph showing ISP achievable with various levels of heating, and the levels appear to be comparable to CO / O combustion, which is also discussed.

(th)

pg 3 shows the heating

This is the satelite use

https://arc.aiaa.org/doi/pdf/10.2514/6.2014-3759

Cold Gas Propulsion System Conceptual Design for the SAMSON NanoSatellite

Offline

Like button can go here

#40 2019-04-09 12:39:55

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 23,516

Re: Mars Co2 or other compressed Gas Hopper rocket

Review of paper on "carbon dioxide thermal rocket" Begin:

A carbon dioxide thermal rocket that utilizes an

indigenous resource in raw form for Mars exploration

D-R Yu∗, X-W Lv, J Qin,W Bao, and Z-L Yao

School of Energy Science and Engineering, Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin, People’s Republic of China

The manuscript was received on 11 May 2009 and was accepted after revision for publication on 21 September 2009.

DOI: 10.1243/09544100JAERO617

Abstract: A CO2 thermal rocket that utilizes an indigenous resource directly for propulsion in

Mars is proposed. The cycle of the proposed novel CO2 thermal rocket combines a CO2 power

cycle with a cryogenic cycle, which is driven by solar energy. Filling CO2 after every hop enables

the concept hopper with the CO2 thermal rocket to visit several regions of the planet. The energy

available for consumption in the processes of the proposed CO2 thermal rocket is analysed; the

simulation results obtained by applying the first law of thermodynamics show that the performance of the cycle of the CO2 thermal rocket is improved by properly designing such a system for

the recovery of freezing CO2 cold energy and waste heat during the cryogenic cycle. Furthermore,

the effect of thermodynamic parameters on the performance of the cycle of the CO2 thermal

rocket is evaluated through parametric analysis; the results show that environmental temperature, nozzle inlet temperature, helium mass flowrate, etc. are the factors affecting thrust-specific

power consumption.

Keywords: carbon dioxide thermal rocket, in situ resources utilization, energy recovery, Mars

exploration

1 INTRODUCTION

I am (at this point) wondering why helium is mentioned. The paper is supposed to be about carbon dioxide. (th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#41 2019-04-09 13:12:56

- elderflower

- Member

- Registered: 2016-06-19

- Posts: 1,262

Re: Mars Co2 or other compressed Gas Hopper rocket

I suspect that the helium is used as a heat transfer agent in closed loops in liquefying the gas for storage and/or in reheating it in the rocket.

Offline

Like button can go here

#42 2019-04-09 18:03:59

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 23,516

Re: Mars Co2 or other compressed Gas Hopper rocket

For Elderflower ...

Thanks! I'll look for that as i begin moving through the paper. (th)

I suspect that the helium is used as a heat transfer agent in closed loops in liquefying the gas for storage and/or in reheating it in the rocket.

Offline

Like button can go here

#43 2019-04-09 18:41:02

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 29,933

Re: Mars Co2 or other compressed Gas Hopper rocket

Heated helium is how space x pressurize its tanks of fuel. It was a tank failure that caused the loss of one rockets second stage.

It is also why Nasa wanted more from the base line rocket for when its used for men even with the load and go mode of fueling.

Offline

Like button can go here

#44 2019-06-13 14:36:06

- Zachoi

- Member

- From: Florida

- Registered: 2019-06-13

- Posts: 1

Re: Mars Co2 or other compressed Gas Hopper rocket

Hey guys, I know I'm a little late to the party, but I wanted to contribute a bit of potentially helpful information.

The original idea posted by Louis sounds similar to NASA's Extreme Access Flyers project. I haven't found much recent information about it (I tried to reference an article from 2015 but apparently users are no longer allowed to post links), but I do know that Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University (ERAU) in Daytona Beach, Florida is still working with NASA on the project. More specifically, the Engineering Physics Propulsion Lab (EPPL) has been designing systems for UAV propulsion on Mars using compressed CO2.

Also, kind of related, I was wondering if you guys had any advice for me. I am a graduate student at ERAU beginning my thesis designing an optimal control system for a Martian drone that uses both propellers and compressed CO2. However, after doing some initial research of my own (which is how I found this topic actually), I find myself trying to decide between two options for such a system:

1.) Having a compressed air engine that the CO2 is fed into that can power the propellers in tandem with an electric motor and will recharge the batteries as the compressed air engine runs, just like a hybrid car works,

2.) Simply having both propellers and cold gas thrusters that work together to produce thrust and attitude correction.

Do you have any thoughts on either system? The goal is to maximize flight time (or flight distance I suppose, but one would assume that the two are closely related).

Hope the information above helps!

Offline

Like button can go here

#45 2019-06-13 16:12:20

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 29,933

Re: Mars Co2 or other compressed Gas Hopper rocket

Welcome to Newmars Zachoi, Nice to see one more US state here with interest in space.

At the bottom of the post box is a link to how to in BBCode, how links will be entered in order for them to show up.

We have a topic on the Mars Helicopter which is riding with the 2020 mission.

Hopefully this will give you some more data for how to make what you want to do possible.

To go with compressed mars air this topic will have data for you.

Then again Airplanes on Mars

I hope these will help...

Offline

Like button can go here

#46 2019-06-14 00:18:30

- Rxke

- Member

- From: Belgium

- Registered: 2003-11-03

- Posts: 3,669

Re: Mars Co2 or other compressed Gas Hopper rocket

Welcome from an old lurker ![]()

Offline

Like button can go here

#47 2019-07-22 19:13:40

Re: Mars Co2 or other compressed Gas Hopper rocket

Hey Zachoi,

Welcome to newmars!

Interesting question and interesting concept.

I'm going to start by restating the question as I understand it to make sure I'm going about answering it in the right way.

You're designing a drone to fly over the surface of Mars which you'd like to power with compressed CO2. You want to figure out the most efficient way to use this energy source to maximize the range of the drone, and you've come up with two possible alternatives: First, using the compressed CO2 to power an engine to turn a propeller or second to use jets of compressed CO2 in a cold gas thruster, with the aim of maximizing flight time and therefore range. Both alternatives will run in tandem with a system of electric motors (and presumably batteries) familiar from drones on Earth.

I must admit that in reading your post I don't understand why you'd want to design a system using both compressed CO2 and electric propellers. I have limited exposure to principles of aeronautical engineering, but here's how I think about the issue: For any given drone design, you will have a certain amount of payload mass you can dedicate to energy storage/production. In order to maximize range and flight time you will want to maximize the number of newton-seconds you can get out of that mass. You will therefore look at your options, determine the efficiency of each, and dedicate 100% of that available mass to the most efficient one, providing for redundant systems where necessary.

I discussed the energy storage ability of compressed CO2 at length in this thread and much of what follows is based on information presented there.

One thing I want to push you on specifically is your choice to use CO2. I can see the appeal, maybe, if you want your drone to be a sort of hopper, which flies until the battery runs down, then lands to recharge (in this case, recharging by running the engines backwards to compress atmospheric gas), then taking off again. If this is your goal (much more complicated than a drone that flies until it runs out of power and then crashes!) then CO2 is the only gas you could potentially use (atmospheric separation would be crazy for this sort of mission imo).

Anyway, whatever your plans are I want to address the two scenarios you mentioned and then try to compare them to battery-electric and chemical-fueled engines.

The real problem with CO2 is that, compared to other gases like Nitrogen, it has an extremely low vapor pressure. Consequently, you can't pressurize it very much before it either liquifies or solidifies. This is made worse by the fact that Martian temperatures are much lower than Earth's, and there's no real way for an airborne drone to absorb thermal energy from the ground to vaporize CO2. For reference, at 230 K (typical Martian temperature), CO2's vapor pressure is 10 atmospheres; Nitrogen and Helium are far above their critical points and therefore cannot liquefy at any pressure, and for reference it is not unusual for bottles of compressed N2 or He to have pressures of 150 atm or above in regular commercial use. Cold gas thrusters using Nitrogen can see specific impulses as high as 75 s (for comparison, the SSME got 450 s). Isp scales in proportion to the inverse square root of the molar mass, so you might get up to 200 s with compressed Helium (which is, uh, pretty good actually?).

Anyway, to get back on track CO2 has both a lower possible pressure and a higher molecular mass than either of those gases; Accounting for molar mass alone you're looking at about 60 seconds, but the low vapor pressure really limits the possible expansion ratios and I'd be surprised if you could hit 20 s. That's 200 newton-seconds per kilogram of compressed CO2, which frankly is awful given that the gas itself is a pretty low density and requires comparatively heavy tanks to store.

When they can work, propeller-based systems are inherently more efficient ways to generate impulse than rocket-based systems because they move more mass at slower speeds. Ideal conditions for propellers are slow travel speeds through a dense medium (Think boats). Whatever the travel speed, Mars's atmosphere is not a dense medium and the design of a propeller that will work in it is nontrivial. Presumably what you want is a very large one with a low speed of rotation. Frankly I have nothing to contribute here. What I'm trying to get at is that there's no good way to make an apples-to-apples comparison between a cold gas thruster and a propeller system. If the propeller works it will presumably be better, but that's a tautologically true and therefore useless statement.

-Josh

Offline

Like button can go here

#48 2019-07-22 21:07:40

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 29,933

Re: Mars Co2 or other compressed Gas Hopper rocket

Thanks for the information of CO2 use for Zachoi, which last logged in or Last visit: 2019-06-21 12:50:13

It would have been nice to have a bit more information as to the rpm, blade characteristics ect....but we can get quite a bit from the heliocopter topic...I am wondering about plane use as well if we augment the wings with a bouyancy gas that can be added and heated to make it more or less bouyant.

Offline

Like button can go here

#49 2019-08-13 20:46:17

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 29,933

Re: Mars Co2 or other compressed Gas Hopper rocket

http://industrialheatpumps.nl/en/how_it … heat_pump/

lots of pages to read

CO2 cooling for HEP experiments

https://cds.cern.ch/record/1158652/files/p328.pdf

Fundamental process and system design issues in CO2 vapor compression systems

http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/do … 1&type=pdf

Offline

Like button can go here

#50 2019-08-14 17:13:11

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 29,933

Re: Mars Co2 or other compressed Gas Hopper rocket

CO2 Tables Calculator - Carbon Dioxide Properties Calculator

https://www.carbon-dioxide-properties.c … esweb.aspx

https://www.kegerators.com/articles/CO2-Tank-Guide/

Compressed gases such as carbon dioxide, oxygen, and nitrous oxide are all gases at room temperature. But get them cold enough, and they become liquid. Get them colder still, and they will become solid - and more concentrated or dense. As these compounds increase in temperature, they also expand in volume. Your CO2 tank is the same way - the pressure increases the hotter the tank (and therefore the CO2 inside) gets.

CO2 expands rapidly as the tank's temperature increases, putting more and more pressure on the gas regulator which controls the CO2 output. The CO2 that the tank has been filled with is very cold (between -57 and -78 degrees degrees). At that temperature, the CO2 puts out only 100 PSI (pounds per square inch). At room temperature (70 degrees), the tank puts out about 850 PSI, and at hot temperatures (around 110 Degrees), the tank can put out a whopping 2000 PSI. If your tanks are ever in the position to be raised to that high of a temperature, the release valve will be triggered to prevent the tank from exploding. This can be quite startling, so it is wise to take steps to avoid this by storing your tank in a cool place, even while disconnected. This is why CO2 tanks are filled to only 34% of their volume. If the tank is filled more, it can trigger the safety and let all the gas out if it is exposed to high temperatures.

Keeping the fuel tank of liquid co2 with a flow valve that send the fuel to a secondary tank that gets super heated to allow for the gas to pressurize before letting it flow out a rocket nozzle.

Offline

Like button can go here