New Mars Forums

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

Announcement

#201 2018-08-06 19:17:23

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,354

Re: Smallest Human Ascent or Descent Lander for Mars Or Earth

Fully recoverable Dragon cargo capsule

Overall Length: 6.1 m (20 ft)

Max Diameter: 3.7 m (12.1 ft)

Dry Mass: 4,200 kg (9,260 lbs)

Propulsion: 18 x Draco thrusters

Propellant: NTO / MMH

Payload Volume:

7 to 10 m3 (245 ft3) pressurized

• Trunk jettisoned prior to reentry

Power: twin solar panels providing 1,500 W average, 4,000 W peak, at 28 and 120 VDC

Payload Volume:

14 m3 (490 ft3) unpressurized

34 m3 (1,200 cu ft) unpressurized with extended trunk

Maximum LEO Falcon 9 Capacity with a payload shroud 10,459 kg (22,990 lbs)

• 6,000 kg (13,228 lbs) total combined up-mass capability

• Up to 3,000 kg (6,614 lbs) down mass

When I find the mass statements for the truck and fuel will add them in for the post plus the legs to have the values for scaling them.

Offline

Like button can go here

#202 2018-08-06 21:52:39

- GW Johnson

- Member

- From: McGregor, Texas USA

- Registered: 2011-12-04

- Posts: 6,131

- Website

Re: Smallest Human Ascent or Descent Lander for Mars Or Earth

Spacenut:

I worked out an analysis spreadsheet that sizes configurations for two types of Mars landers. These are one-stage, two-way, reusable vehicles, and two-stage, two-way, non-reusable vehicles. The spreadsheet includes a worksheet for guessing inert mass fractions in an organized way. If you email me that you want it, I'd be happy to send it to you. Or anyone else on these forums.

I used it to run a design study on these two types of landers. What I found was the storable propellants work best, due to the months of transit to Mars. The increase in inert hardware to offset the boiloff negates the higher specific impulse effect, for LCH4-LOX vs MMH-NTO. I wrote it all up in considerable detail, and posted it over at my blog site, exrocketman.blogspot.com.

There is a navigation tool on the left: click on 2018, then August, then the title "Exploring Mars Lander Configurations". Right now, it is the latest thing I have posted.

The article also gives the date and title for another article I posted last year, where I reported my reverse engineering of what the various versions of the Spacex Dragon can do. That one predates cancellation of Red Dragon, so my estimates for what Red Dragon could do are there, as well as crew Dragon, and cargo Dragon. I had to make some assumptions, but they are realistic and well-identified in the article. Most of the source data is what Spacex has published.

GW

Last edited by GW Johnson (2018-08-06 22:11:08)

GW Johnson

McGregor, Texas

"There is nothing as expensive as a dead crew, especially one dead from a bad management decision"

Offline

Like button can go here

#203 2018-08-07 16:29:58

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,354

Re: Smallest Human Ascent or Descent Lander for Mars Or Earth

Thank you for the offer. Will dig through your site to search out more information as well.

Continuing to post the details that I have found thus far to aid in the scope of what do we need in a first mission to mars.

Dragon v2 manned capsule

same baseline size with a new mold line shape to accomodate the Eight side-mounted SuperDraco engines, clustered in redundant pairs in four engine pods, with each engine able to produce 71 kilonewtons (16,000 lbf) of thrust. They consumed their nearly two-ton load of hydrazine and nitrogen tetroxide propellant in less than six seconds, pushing the Dragon capsule a third of a mile above Cape Canaveral with a top speed of 345 mph. The capsule hovered in equilibrium for about 5 seconds, kept in balance by its 8 engines firing at reduced thrust to compensate exactly for gravity.

The legs on the Falcon 9 first stage:

https://www.reddit.com/r/spacex/comment … eg_design/

Current stage is about 25t at landing and has diameter of 3.7 m.

By the square-cube law, you'll need legs with cross-sectional area 8 times larger. If you only have 4 legs, you'll need legs with horizontal side of sqrt(8) = 2.83 times more than what we currently have.

Four legs, which are made of carbon fiber with aluminum honeycomb, will be placed symmetrically around the base of the rocket.

Offline

Like button can go here

#204 2018-08-07 18:58:11

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 8,465

Re: Smallest Human Ascent or Descent Lander for Mars Or Earth

GW,

I'd like a copy of that spreadsheet. I want to see if I can make a HTML page out of it using JavaScript. Maybe we can create a tools section to this website that has online tools for estimating mass and performance for Mars missions.

Offline

Like button can go here

#205 2018-08-07 20:01:12

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,354

Re: Smallest Human Ascent or Descent Lander for Mars Or Earth

I do agree with that and Hope that we can push the technology we have to get the job done.

Offline

Like button can go here

#206 2018-08-09 07:58:43

- GW Johnson

- Member

- From: McGregor, Texas USA

- Registered: 2011-12-04

- Posts: 6,131

- Website

Re: Smallest Human Ascent or Descent Lander for Mars Or Earth

Just found the Mars lander spreadsheet request from Kbd512. It's on its way to your email. That's you and Spacenut so far.

Have fun with the silly thing. It's just playing games with the rocket equation, mass fractions, and some jigger factors for things like gravity and drag losses.

The article on "exrocketman" where I looked at landers with this spreadsheet is drawing a lot of readership.

Sorry there's no user's manual for the spreadsheet. The article is the closest thing to a user's manual that I have. The usual user inputs are highlighted yellow.

GW

GW Johnson

McGregor, Texas

"There is nothing as expensive as a dead crew, especially one dead from a bad management decision"

Offline

Like button can go here

#207 2018-08-31 18:17:07

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,354

Re: Smallest Human Ascent or Descent Lander for Mars Or Earth

After seeing the Mars society poster on the home page I got thinking about landing on mars again.

Section 10. Mars Ascent Vehicle

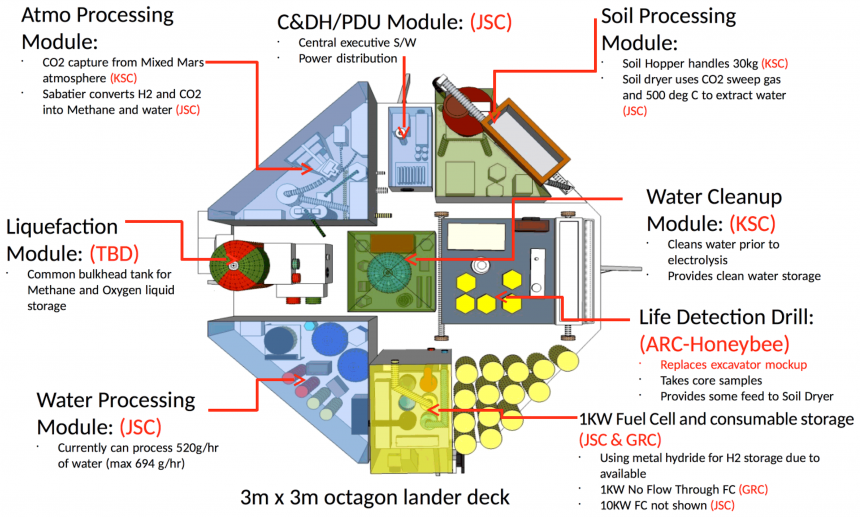

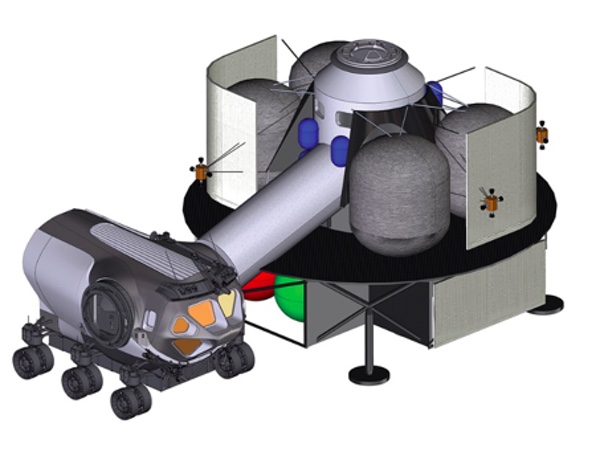

MARCO POLO is a robotic technology demonstration mission comprised of an octagonal lander and mobile robot, which process Martian soil and atmosphere to produce O2, H2O and CH4.

https://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi … 006401.pdf

Mars Ascent Vehicle Design for Human Exploration

https://esto.nasa.gov/conferences/nstc2 … 7-0015.pdf

Pump Fed Propulsion for Mars Ascent and Other Challenging Maneuvers

www.seas.upenn.edu/~utopcu/pubs/TCM-space07.pdf

Minimum-Fuel Powered Descent for Mars Pinpoint Landing

Offline

Like button can go here

#208 2018-09-02 03:58:17

- elderflower

- Member

- Registered: 2016-06-19

- Posts: 1,262

Re: Smallest Human Ascent or Descent Lander for Mars Or Earth

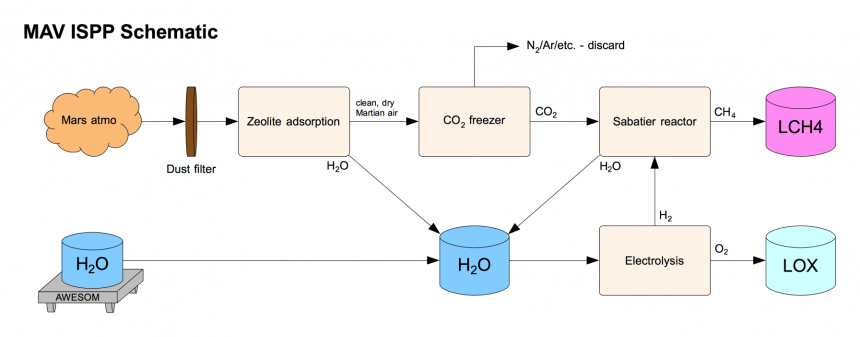

Schematic makes it look simple to get LOX and Methane. It isn't. The schematic omits compression, heat exchange refrigeration and liquefaction and cryopump, to say nothing of purification of water and CO2 feed and power supplies.

Offline

Like button can go here

#209 2018-09-02 08:33:08

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,354

Re: Smallest Human Ascent or Descent Lander for Mars Or Earth

As well as dust /dirt for the Co2 intake, and the mining for the water or other methods to gaining the ingrediences that we need to be able to make Methane and Oxygen.

Offline

Like button can go here

#210 2018-09-02 09:43:33

- GW Johnson

- Member

- From: McGregor, Texas USA

- Registered: 2011-12-04

- Posts: 6,131

- Website

Re: Smallest Human Ascent or Descent Lander for Mars Or Earth

A lot of folks see these press releases and do not recognize the mostly-hype that they really are. Most of this stuff is nowhere near ready to bet your life on.

Making some methane and oxygen out of tap water and bottled carbon dioxide in a lab benchtop demonstration machine is one hell of a long way from a portable (!!!) factory you can land on a harsh planet, and get from it propellant-quality (!!!) methane and oxygen, liquify them, store them without significant boiloff losses, and do this in 1100 ton quantities on a 2 to 4 year timescale! And do it from polluted and thinly-spread resources!!!

Martian air is not pure carbon dioxide. The ice may or may not be salty. If it is salty, perhaps that can be the electrolyte for electrolysis. I dunno, I am not a professional chemist. (Damp regolith is an impractical resource, you need massive ice deposits.)

There's going to be fine dust everywhere on dry windy desert planet. I'm not sure whether it is as sharp and abrasive as moon dust, but even Earthly desert dust destroys or shortens the life of machinery.

But without that working propellant factory, every BFS Musk sends to Mars is stranded there, even if it survives the rough-field landing in a tall vehicle (a severe risk!!!). So from who, exactly, will he buy this propellant factory?

I have fair confidence he might make his BFR/BFS system fly. He might even be ready to do on-orbit refilling from tankers so he can send some BFS's to Mars in a few years. So, who is he going to buy the propellant factory from? Will it be ready (meaning fully field-tested!!!) in a few years?

I don't see any outfits working that problem. I don't mean science lab experiments (and that octagonal lander to experiment with propellant-making on Mars is a MUCH BETTER lab experiment, but a lab experiment nonetheless), I mean real engineering development and field-testing. So who is doing THAT?

If nobody is working the real engineering development NOW, then how is that machinery going to ready to bet lives on in a few years?

Sorry, reality checks are unpleasant. But very necessary.

GW

Last edited by GW Johnson (2018-09-02 09:51:10)

GW Johnson

McGregor, Texas

"There is nothing as expensive as a dead crew, especially one dead from a bad management decision"

Offline

Like button can go here

#211 2018-09-02 12:03:23

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,354

Re: Smallest Human Ascent or Descent Lander for Mars Or Earth

Prototyping up a demonstrator to land on mars is hard work that comes with piece trials to see what will fit into the capability to land and to make them work with the power source that we send with it. Its that final intergration that is the hardest to do.

MARCO POLO/Mars Pathfinder in-situ resource utilization, or ISRU, system recently took place at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida. A mockup of MARCO POLO, an ISRU propellant production technology demonstration simulated mission, was tested in a regolith bin with RASSOR 2.0, the Regolith Advanced Surface Systems Operations Robot.

Regolith Advanced Surface Systems Operations Robot

This is the rovering miner video with yet another acronym for the naming of RASSOR, MARCO POLO Demonstrate Resource Utilization on Mars

Demonstrations such as this one help scientists learn how to extract critical resources on site – even as far away as the Red Planet. RASSOR excavated regolith and delivered sand and gravel to a hopper and mock oven.

On the surface of Mars, mining robots like RASSOR will dig down into the regolith and take the material to a processing plant where usable elements such as hydrogen, oxygen and water can be extracted for life support systems. Regolith also shows promise for both construction and creating elements for rocket fuel.

Offline

Like button can go here

#212 2018-09-02 15:36:55

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 8,465

Re: Smallest Human Ascent or Descent Lander for Mars Or Earth

GW,

That's because such a LOX/LCH4 plant doesn't exist. That's why the upper stage needs to be LOX/LH2. If storing it here on Earth isn't a major problem, then it's not a major problem on Mars. For $26M, you can have your own multi-megawatt class LOX/LH2 plant in a container that is light enough and small enough to fit aboard a BFS. Proton OnSite's LOX/LH2 plant is an incredible bargain in the world of space flight.

If SpaceX wants their BFS concept to start sending people to Mars in a few short years, then they need to buy J-2 or RS-25 engines for their upper stage (already reusable and flight proven), rework the tankage volumes (little to no additional volume is required to achieve the same payload performance since the upper stage is lighter, especially with IVF), buy the LOX/LH2 plant (real working technology used here on Earth to obtain H2 from water), and get on with testing it. That's what a realistic development program with a near-term timeline will look like.

Offline

Like button can go here

#213 2018-09-02 18:22:29

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,354

Re: Smallest Human Ascent or Descent Lander for Mars Or Earth

The engines could be bought but they would be upward of $100 million a piece or more, which would drive things way up for Space X.

After a few days the amount of fuel would be dropping and we would need to have lots of rockets ready to launch more fuel to top it off before heading off to mars.

https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/shut … orage.html

Liquid oxygen used as an oxidizer by the orbiter main engines is stored in a 900,000-gallon tank on the pad's northwest corner, while the liquid hydrogen used as a fuel is kept in an 850,000-gallon tank on the northeast corner.

The liquid oxygen tank functions as a huge vacuum bottle designed to store the cryogenic fluid at a very low temperature -- less than minus 297 degrees Fahrenheit. It is transferred to the pad by one of two main pumps capable of pumping 1,300 gallons per minute.

The lighter liquid hydrogen is stored in a vacuum bottle located in the northeast corner of each pad. It must be kept at an even lower temperature than the liquid oxygen: minus 423 degrees F.

Offline

Like button can go here

#214 2018-09-02 18:47:04

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,354

Re: Smallest Human Ascent or Descent Lander for Mars Or Earth

Liquid Oxygen and Liquid Hydrogen, usually is burned in about 6:1 ratio of oxygen to hydrogen is considered to be the ultimate in rocket performance. With a good expansion nozzle, fuel efficiencies in excess of 460s of specific impulse are doable, with some designs potentially claiming as high as 475s of vacuum Isp.

Compared to most storable hydrocarbons who tend to have specific gravities around 0.7-0.8, hydrogen’s specific gravity is a measly 0.07! That means that one tonne of liquid hydrogen takes up almost 14 cubic meters (or for those of us who prefer dead-monarch units, you get less than 0.5lb of the stuff per gallon).

NASA Perspectives on Cryo H2 Storage

The SLS first stage tank measurement is more than 130 feet tall, the liquid hydrogen tank is the largest cryogenic fuel tank for a rocket in the world,” according to NASA. And it is truly huge – measuring also 27.6 feet (8.4 m) in diameter. The LH2 and LOX tanks sit on top of one another inside the SLS outer skin. Together the hold over 733,000 gallons of propellant. The LH2 tank is the largest major part of the SLS core stage. It holds 537,000 gallons of super chilled liquid hydrogen. It is comprised of 5 barrels, 2 domes, and 2 rings. The LOX tank holds 196,000 pounds of liquid oxygen. It is assembled from 2 barrels, 2 domes, and 2 rings and measures over 50 feet long.

From the Shuttle era NASA bought hydrogen at 98 cents per gallon. A gallon of liquid hydrogen weighs 0.2679 kg, so they paid $3.66 per kg for liquid hydrogen. NASA bought oxygen at 67 cents per gallon. A gallon of liquid oxygen weighs 4.322 kg, so they paid $0.16 per kg for liquid oxygen.

Offline

Like button can go here

#215 2018-09-02 18:53:47

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,354

Re: Smallest Human Ascent or Descent Lander for Mars Or Earth

An article from a few years ago Solving the expendable lander and MAV trap

It is significant that it takes only about 75 tons of LOX and LH2 propellant to bring 25 tons of the same propellant from the lunar surface to L1 or L2, including a round trip back to the Moon for the tanker.

Offline

Like button can go here

#216 2018-09-02 22:44:05

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 8,465

Re: Smallest Human Ascent or Descent Lander for Mars Or Earth

SpaceNut,

A few points to ponder...

The US tax payer could fund the propulsion development for the BFS since USAF is already funding the reusable Raptor booster engine program. BFR and New Glenn will eventually become the work horse of our future military space program. SLS is just a painful stumbling block on the way to something better. LOX/LCH4 is an ideal booster propellant combo, but LOX/LH2 is an ideal upper stage propellant combo. We're well aware of the problems associated with using LH2 and we have lots of existing infrastructure and know-how directed towards the use of LH2. No other fuel is as well understood and characterized by America's space program. Do you want to throw 4 to 5 perfectly good RS-25's in the Atlantic or Pacific after we use them for 8 minutes or do you want to see those engines execute as many missions as they can before retirement?

People need to learn to separate the Space Shuttle orbiter vehicle and its litany of problems from the RS-25, which performed as near to flawlessly as anyone could hope for. Buy once, cry once. The RS-25's work and there's no denying that fact. There have been exactly zero engine failures in more than 3 decades of operational use and zero is the only correct number of upper stage engine failures. We already know what parts break on the RS-25's and therefore what parts to keep aboard BFS for engine repairs. The use of RS-25's is the most cost effective way to fast-track the BFR program and provide a reusable SSTO or suborbital transport that uses thoroughly proven flight hardware.

Furthermore, a BFR upper stage with the propellant capacity of the SLS core stage would deliver well over 200t to LEO using an equivalent mass design. The inert / structural mass of a RS-25 equipped BFS would produce a total wet vehicle mass that's nearly identical to the Raptor equipped BFS. There's nothing inherently wrong with making the upper stage larger in diameter, either. We need a wide-track lander to successfully land on unprepared surfaces, which happens to be the only kind of surface currently available on the moon or Mars. Even on a steel or concrete pad or runway, having a wider landing gear track always helps stability.

Offline

Like button can go here

#217 2018-09-03 11:09:30

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,354

Re: Smallest Human Ascent or Descent Lander for Mars Or Earth

The existing reuseable RS-25 engines will be gone with in just 3 flights of SLS and after that its going to remain is the expendable version to which is a new engine as the rehash with a new brain was done to its design.

https://www.nasa.gov/exploration/system … aphic.html

https://www.nasa.gov/exploration/system … s-sls.html

Fine for a first stage but its not a restartable engine so it make a no go for a second stage....even in the expendable format....

I still have not found a definative answer as to why the J2X or other version are not being used after all the rehash of it.

Offline

Like button can go here

#218 2018-09-03 13:45:13

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 8,465

Re: Smallest Human Ascent or Descent Lander for Mars Or Earth

SpaceNut,

From DARPA's AR-22 (RS-25 variant) press release:

Experimental Spaceplane Program Successfully Completes Engine Test Series

From the article:

The RS-25 engine family has a history of more than one million seconds of runtime, demonstrating its maturity. This test series is the first time engineers had operated it in an aircraft-like fashion with such repetition. Achieving this level of performance required engineers to streamline the maintenance and turnaround procedures to only what was truly necessary. That meant, for example, understanding and running with the kind of natural wear-and-tear associated with aircraft engines, without compromising reliability, safety, or performance. After each run, the team analyzed myriad recorded data to assess the engine’s health. These rapid, yet accurate, assessments were made possible by decades of prior SSME data.

Another significant challenge of the series was rapidly drying the engine between tests. The propellants – liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen – combine to create liquid water that accumulates internally. If the engine is chilled down and restarted with excessive internal water, damage could result. Typically, engineers have weeks to let an engine dry between tests, but to meet the demands of 24-hour turnaround, the team introduced new processes to cut the drying time first to eight hours and then down to six.

"With each successful milestone, we’re closer to the goal of driving down cost and time to space by an order of magnitude," said Scott Wierzbanowski, DARPA program manager for the Experimental Spaceplane. "For instance, we’re targeting the ability to affordably turn the vehicle within a day. If successful, we will be able to launch payloads on demand, which will change the paradigm for how the nation uses space."

Perhaps RS-25 (AR-22) wasn't restartable before, but it is now. J-2X was not being used because in the narrow design performance envelope of an upper stage for SLS, they achieved better performance (more payload) using RL-10's. J-2X was brought back online to use in Ares-I. J-2X and RL-10C were both designed for multiple in-flight restarts and now AR-22 (RS-25) is being tested to do the same thing for the military's Space Plane project, which means SpaceX and Blue Origin don't have to pay for high performance upper stage engine development.

Offline

Like button can go here

#219 2018-09-03 16:23:54

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,354

Re: Smallest Human Ascent or Descent Lander for Mars Or Earth

Thanks for that link kbd512

Then, starting July 26, the engineering team successfully fired the engine 10 times in just under 240 hours. All firings lasted at least 100 seconds. The AR-22 engine is a variant of the RS-25, also known as the Space Shuttle Main Engine (SSME).

The Experimental Spaceplane program is a public-private partnership between DARPA and Boeing. Boeing teamed with Aerojet Rocketdyne for the AR-22. The program is in the second of three phases, the final of which is a flight test targeted for early 2021. Highlights of the unmanned Experimental Spaceplane include:Automated flight termination and other technologies for autonomous flight and operations;

Capability to deploy at least 3,000 pounds to low Earth orbit; and

Design that accommodates different types of upper stages.

Seems to be an off shut from the x37 space plane program....

The expendable is actually Identified NASA defends decision to restart RS-25 production, rejects alternatives as the RS-25E

http://www.americaspace.com/2015/11/24/ … n-for-sls/

when the original shuttle-era RS-25D inventory is exhausted, a new RS-25E will be introduced, capable of up to 521,700 pounds (236,640 kg) of thrust. “The new engines will be certified for flight at 111-percent thrust,”

Offline

Like button can go here

#220 2018-09-03 21:11:27

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,354

Re: Smallest Human Ascent or Descent Lander for Mars Or Earth

We know that the atmosphere of mars is just got to give up its CO2 willing but running the energy and mass numbers are saying anything but for being easy.

NASA will pay you up to $750,000 to come up with a way to turn CO2 into other molecules on Mars

https://www.co2conversionchallenge.org/#home

To start, NASA is asking teams to focus on converting CO2 to Glucose, but the language of the challenge suggests you can approach that goal from any angle you wish:

Teams or individuals who want to participate will need to register by January 24, 2019, and then officially apply by February 28. Experts will review each plan and award up to $250,000 spread across up to five individuals or teams.

The next phase of the competition is still a bit light on details. NASA says it’ll announce the rules and criteria once Phase 1 is complete, but the administration has revealed that it’s ready to award up to $750,000 to the individual, team, or teams that can demonstrate that their system(s) work as intended and could be used by astronauts on Mars.

Offline

Like button can go here

#221 2018-09-04 05:39:30

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 8,465

Re: Smallest Human Ascent or Descent Lander for Mars Or Earth

SpaceNut,

Use RamGen. You need a 3 stage 10 to 1 supersonic CO2 compressor. If they really can't figure this out, then I guess they can't. However, they funded RamGen. If they're ignorant of what they're throwing money at, then I guess they are.

Offline

Like button can go here

#222 2018-09-04 18:39:40

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,354

Re: Smallest Human Ascent or Descent Lander for Mars Or Earth

We know the science, the require identification equipment and what it will take to process what we want from insitu materials but what we do not have defined is the quantity, quality of specific insitu items that we can gain from mars.

The only 1 that we have confirmed for quality and quantity is in mars atmosphere.

Thanks for the RamGen as I went to find out more.

It is not just a compressor as it cools the gas as it brings up the pressure of it.

http://www.ramgen.com/apps_comp_unique.html

It is for a coal burning plant exhaust at earth atmospheric pressure at the inlet.

https://www.netl.doe.gov/research/coal/ … supersonic

Offline

Like button can go here

#223 2018-09-10 20:01:56

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,354

Re: Smallest Human Ascent or Descent Lander for Mars Or Earth

Folding heatshield has been around for awhile...

www.iaeng.org/publication/WCE2017/WCE2017_pp906-911.pdf

Adjustable Aerobraking Heat Shield for Satellites Deployment and Recovery

Offline

Like button can go here

#224 2018-09-12 19:51:12

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,354

Re: Smallest Human Ascent or Descent Lander for Mars Or Earth

Exploring the Solar System? you may need to pack an umbrella. ADEPT is a foldable device that opens to make a round, rigid heat shield, called an aeroshell.

ADEPT's first flight test is scheduled for Sept. 12 from Spaceport America in New Mexico aboard an UP Aerospace suborbital SpaceLoft rocket. ADEPT will launch in a stowed configuration, resembling a folded umbrella, and then separate from the rocket in space and unfold 60 miles above Earth.

The test will last about 15 minutes from launch to Earth return. The peak speed during the test is expected to be three times the speed of sound, about 2,300 miles per hour.

That is not fast enough to generate significant heat during descent, but the purpose of the test is to observe the initial sequence of ADEPT's deployment and assess aerodynamic stability while the heat shield enters Earth's atmosphere and falls to the recovery site.

This umbrella-like mechanical aeroshell design uses flexible 3D woven carbon fabric skin stretched over deployable ribs and struts, which become rigid when fully flexed. The carbon fabric skin covers its structural surface, and serves as the primary component of the entry, descent and landing thermal protection system.

"Carbon fabric has been the major recent breakthrough enabling this technology, as it utilizes pure carbon yarns that are woven three-dimensionally to give you a very durable surface," said Wercinski. "Carbon is a wonderful material for high temperature applications."

The next steps for ADEPT are to develop and conduct a test for an Earth entry at higher "orbital" speeds, roughly 17,000 miles per hour, to support maturing the technology with an eye towards Venus, Mars or Titan, and also returning lunar samples back to Earth.

Offline

Like button can go here

#225 2018-09-13 15:22:22

- GW Johnson

- Member

- From: McGregor, Texas USA

- Registered: 2011-12-04

- Posts: 6,131

- Website

Re: Smallest Human Ascent or Descent Lander for Mars Or Earth

The first time I saw a thing like this was in the movie 2010 Odyssey 2. That one was an inflatable used for an aerobraking pass at Jupiter. But it's still the same idea. Add a lightweight structure in a way that greatly increases blockage area while minimally increasing mass. That reduces ballistic coefficient.

I'm glad folks are really working on this. It will be a game-changer at Mars, and perhaps elsewhere. But, those folks have a long way to go before this technology is read-to-apply.

GW

GW Johnson

McGregor, Texas

"There is nothing as expensive as a dead crew, especially one dead from a bad management decision"

Offline

Like button can go here