New Mars Forums

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

Announcement

#1 2017-10-02 21:26:57

- EdwardHeisler

- Member

- Registered: 2017-09-20

- Posts: 357

SpaceX's new plan to get to Mars BFR comparison and summary

Published on Sep 29, 2017

Elon Musk revealed the update to SpaceX’s highly anticipated and ambitious rocket, the BFR. We compare this version of the BFR to last year’s version as well as speculate about SpaceX's mind blowing plans to head to the Moon, Mars as well as anywhere on Earth within one hour!

See the video at this link:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i_3GPpI … e=youtu.be

BFR: Elon's 2017 Mars Plan Explained!

Published on Sep 29, 2017

BFR, the New Mars colonization plan was unveiled today. I think it's pretty exciting, keeping the plan grounded, thinking for the future. Although the timeline still is a bit aggressive, overall I think SpaceX is on the right track. Hope you guys like this video.

Offline

Like button can go here

#2 2017-10-02 21:38:51

Re: SpaceX's new plan to get to Mars BFR comparison and summary

I tuned into his live presentation on Friday and was utterly fascinated. I think he has developed a manageable and reasonable plan. His rocket--about 50% bigger than a Saturn V in total mass, but reusable--looks doable. The idea of it replacing Falcon and Dragon is startling, but if it really is reusable, the cost of burning 4,500 tonnes of methane and oxygen to send an 85-tonne vehicle and up to 150 tonnes of cargo to ISS or anywhere else in low Earth orbit is probably financially reasonable. That much fuel is only a few million bucks, after all, and if the reusable vehicle costs $40 or $50 million per flight, the overkill in terms of size is financially viable. More than that: one could replace ISS with something much bigger very cheaply. If you can launch an 85 tonne vehicle into low Earth orbit with 40 cabins each able to hold several people, one could easily imagine 100 tourists at a time going to low Earth orbit and just staying on the vehicle for a few days; it could serve as a temporary orbital hotel. If Bigelow can build something able to accommodate 100+ tourists at a time, Musk's vehicle could make weekly flights, taking new tourists up and then bringing last week's tourists back to Earth! I suspect there's a lot of money to be made that way if the tickets are less than a million bucks, which they would eventually be, if this system can get people to Mars cheaply.

While last time Musk gave prices for building the BFR and the second stage, it is interesting that he did NOT offer such numbers this time, even though the vehicles are smaller. One can only wonder whether he has a more realistic (and more expensive) estimate of the costs now. The new system for landing will require a whole new development budget.

Offline

Like button can go here

#3 2017-10-03 09:26:42

- louis

- Member

- From: UK

- Registered: 2008-03-24

- Posts: 7,208

Re: SpaceX's new plan to get to Mars BFR comparison and summary

RobS -

It is an impressive plan.

In terms of cost, one of the advantages of the plan is that it is spreading development, production and coms costs over at least two and maybe up to six separate projects: ISS supply, satellite launches, orbital tourism, lunar tourism, long range Earth flight and Mars exploration/settlement. We know ISS supply and satellite launches are highly profitable. I think orbital and lunar tourism could become equally profitable. The feasibility of long range Earth flight remains to be seen. But essentially the profit streams can be used to fund the Mars Mission's share of the costs.

I tuned into his live presentation on Friday and was utterly fascinated. I think he has developed a manageable and reasonable plan. His rocket--about 50% bigger than a Saturn V in total mass, but reusable--looks doable. The idea of it replacing Falcon and Dragon is startling, but if it really is reusable, the cost of burning 4,500 tonnes of methane and oxygen to send an 85-tonne vehicle and up to 150 tonnes of cargo to ISS or anywhere else in low Earth orbit is probably financially reasonable. That much fuel is only a few million bucks, after all, and if the reusable vehicle costs $40 or $50 million per flight, the overkill in terms of size is financially viable. More than that: one could replace ISS with something much bigger very cheaply. If you can launch an 85 tonne vehicle into low Earth orbit with 40 cabins each able to hold several people, one could easily imagine 100 tourists at a time going to low Earth orbit and just staying on the vehicle for a few days; it could serve as a temporary orbital hotel. If Bigelow can build something able to accommodate 100+ tourists at a time, Musk's vehicle could make weekly flights, taking new tourists up and then bringing last week's tourists back to Earth! I suspect there's a lot of money to be made that way if the tickets are less than a million bucks, which they would eventually be, if this system can get people to Mars cheaply.

While last time Musk gave prices for building the BFR and the second stage, it is interesting that he did NOT offer such numbers this time, even though the vehicles are smaller. One can only wonder whether he has a more realistic (and more expensive) estimate of the costs now. The new system for landing will require a whole new development budget.

Let's Go to Mars...Google on: Fast Track to Mars blogspot.com

Offline

Like button can go here

#4 2017-10-03 10:04:13

- louis

- Member

- From: UK

- Registered: 2008-03-24

- Posts: 7,208

Re: SpaceX's new plan to get to Mars BFR comparison and summary

The butt to butt refuelling process looks innovative!

Published on Sep 29, 2017

Elon Musk revealed the update to SpaceX’s highly anticipated and ambitious rocket, the BFR. We compare this version of the BFR to last year’s version as well as speculate about SpaceX's mind blowing plans to head to the Moon, Mars as well as anywhere on Earth within one hour!See the video at this link:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i_3GPpI … e=youtu.be

BFR: Elon's 2017 Mars Plan Explained!

Published on Sep 29, 2017

BFR, the New Mars colonization plan was unveiled today. I think it's pretty exciting, keeping the plan grounded, thinking for the future. Although the timeline still is a bit aggressive, overall I think SpaceX is on the right track. Hope you guys like this video.

Let's Go to Mars...Google on: Fast Track to Mars blogspot.com

Offline

Like button can go here

#5 2017-10-03 15:51:42

- Antius

- Member

- From: Cumbria, UK

- Registered: 2007-05-22

- Posts: 1,003

Re: SpaceX's new plan to get to Mars BFR comparison and summary

A round trip to Mars would take over two years. A round trip to the moon could be done in two weeks. The same vehicle could make a hundred trips to the moon in the time it takes for a single Martian round trip. It would be much more sensible at this stage to concentrate resources on a lunar base and build up economy of scale on the launch and transfer vehicles. What's more, a lunar base would be a valuable asset for supporting space manufacturing. With those capabilities, we could build ships capable of shipping thousands of people to the red planet. Accessing Mars will not be possible for ordinary people until we have interplanetary liners.

Last edited by Antius (2017-10-03 15:54:34)

Offline

Like button can go here

#6 2017-10-03 16:40:59

- louis

- Member

- From: UK

- Registered: 2008-03-24

- Posts: 7,208

Re: SpaceX's new plan to get to Mars BFR comparison and summary

The BFR will be an interplanetary liner - it's huge, capable of carrying 150 tonnes.

Building a space manufacturing infrastructure on the Moon (as opposed to Mars) will be extremely difficult. Mars has a wide range of resources - all we have to do is ship out the initial start-up machinery to get things going there.

The big future for the moon is lunar tourism which will then help fund Mars settlement.

A round trip to Mars would take over two years. A round trip to the moon could be done in two weeks. The same vehicle could make a hundred trips to the moon in the time it takes for a single Martian round trip. It would be much more sensible at this stage to concentrate resources on a lunar base and build up economy of scale on the launch and transfer vehicles. What's more, a lunar base would be a valuable asset for supporting space manufacturing. With those capabilities, we could build ships capable of shipping thousands of people to the red planet. Accessing Mars will not be possible for ordinary people until we have interplanetary liners.

Last edited by louis (2017-10-04 02:11:18)

Let's Go to Mars...Google on: Fast Track to Mars blogspot.com

Offline

Like button can go here

#7 2017-10-03 17:49:00

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,397

Re: SpaceX's new plan to get to Mars BFR comparison and summary

The size of the BFR in terms of hieght is going to mean building an unloading system into the very top of the rock to be able to unload the cargo as its a long way down to the surface.

That said the cargo version will be quite different from the units for the people in lots of different ways.

The intial thought is that the cargo units should be reuseable but will they is the question as to what we can product for insitu made fuels from what we deliver in those cargo vehicles.

Offline

Like button can go here

#8 2017-10-03 22:29:54

- Excelsior

- Member

- From: Excelsior, USA

- Registered: 2014-02-22

- Posts: 120

Re: SpaceX's new plan to get to Mars BFR comparison and summary

The size of the BFR in terms of hieght is going to mean building an unloading system into the very top of the rock to be able to unload the cargo as its a long way down to the surface.

That said the cargo version will be quite different from the units for the people in lots of different ways.

The intial thought is that the cargo units should be reuseable but will they is the question as to what we can product for insitu made fuels from what we deliver in those cargo vehicles.

I think they can use the big clamshell door variant shown deploying satellites to alleviate this problem. They just need to design the hinge so that the door can slide down towards the "aft" of the vehicle. That will get the door out of way, and allow a larger crane in the nose to manipulate bulky items.

The Former Commodore

Offline

Like button can go here

#9 2017-10-04 03:14:25

- Antius

- Member

- From: Cumbria, UK

- Registered: 2007-05-22

- Posts: 1,003

Re: SpaceX's new plan to get to Mars BFR comparison and summary

The BFR will be an interplanetary liner - it's huge, capable of carrying 150 tonnes.

It is small by the standards of Earth transportation – capable of ferrying a hundred or so passengers to Mars and making a round trip every 2.5 years. If its lifespan is 30 years that means that each rocket can carry out a dozen or so round trips in the course of its life – maybe 1200 passengers in each direction. On that basis, it will be difficult for the cost of a ticket to drop to much less than $1million, even if economy of scale is maxed out. The same rocket could transport 78,000 passengers to the moon over the course of its life. This suggests to me that the economics of lunar transportation will be much more favorable to a private investor trying to finance the cost of the ticket.

There are other advantages as well. A rocket making short-term trips does not need the sort of life support capabilities that an interplanetary vehicle would need. It will be cheaper to build and could presumably carry more passengers per trip.

Building a space manufacturing infrastructure on the Moon (as opposed to Mars) will be extremely difficult. Mars has a wide range of resources - all have to do is ship out the initial start-up machinery to get things going there.

It will be difficult to build space manufacturing anywhere. But it will be much cheaper to ship infrastructure to the moon as opposed to Mars, for the reasons already discussed. From what we know, the moon has a harsher environment with less accessible resources. But it is much easier to transport those resources from the surface into high Earth orbit, where there are markets for things like solar power satellites and space hotels. And of course there is then the potential to build truly interplanetary ships, weighing thousands of tons and driven by mass drivers and transporting thousands of people at a time to places like Mars, Ceres and the Asteroids. That sort of capability would really open the solar system to human colonization.

The big future for the moon is lunar tourism which will then help fund Mars settlement.

I don't think lunar tourism will ever be a very big market. The place is like an Earth desert without air. There will be a few people prepared to pay a million dollars to do it for the sheer novelty value. But most people spending that sort of money will need to see financial return. Low Earth orbit has better potential for tourism. If the BFR could make round trips to low Earth orbit in a timescale of hours, it's economics would be more like those of a jet aircraft, with costs <$100/kg. At that price, low orbit tourism will be achievable as a once in a lifetime holiday for quite a lot of people, but they will want to do exciting things when they get there. They will want spacious hotels, all-inclusive dining, zero-G swimming pools, etc. To build the sort of infrastructure needed to make this workable will take tens of thousands of tons of materials. Even with the BFR, you could not realistically launch it from Earth.

Offline

Like button can go here

#10 2017-10-04 05:00:06

- Terraformer

- Member

- From: The Fortunate Isles

- Registered: 2007-08-27

- Posts: 3,994

- Website

Re: SpaceX's new plan to get to Mars BFR comparison and summary

I'm a Luna-first person. Particularly given the water ice that we've detected. We need propellent depots anyway if we're going to launch the big missions, so why haul all the propellent up a steep gravity well when you can mine it on our moon?

The way I see space settlement being for the next several decades is similar to Antarctica and the high seas. There won't be any permanent colonies (unless Mars turns out to be trivial to proteroform...), but there will be thousands of people on Luna and Mars, and maybe other locations, working at science outposts (as in Antarctica), mining camps (like oil rigs), or hotels (akin to cruise ships). If we're lucky, these will lay the groundwork for homesteads and cities to be built.

Of the two worlds (Mars and Luna), I think Luna has the best near-future profitability, due to it's proximity. It has (some) water and minerals which could be mined. It's a useful place for a science base, for example radio astronomy on the farside, as well as studying the moon itself. It's close enough that tourists could visit. Launch windows aren't the problem they are for Mars. Solar power is far more plentiful at the poles. By focusing on Luna first, we can build up an infrastructure that will make it easier to get science bases going on Mars, as well as support the exploration and exploitation of near earth asteroids.

Use what is abundant and build to last

Offline

Like button can go here

#11 2017-10-04 08:51:25

- Oldfart1939

- Member

- Registered: 2016-11-26

- Posts: 2,489

Re: SpaceX's new plan to get to Mars BFR comparison and summary

We really DON'T KNOW how much water is on the moon, and it could be a very scarce but valuable resource. Principally, it should be used for a moon base, and not squandered. The moon base should have first rights to any lunar ice deposits in order to maintain that colony/base of operations. Manufacturing rocket fuel requires enormous amounts of feedstock for a energy consumptive process. A moon base will be consuming both Oxygen and water. Using liquid H2 as a fuel is fraught with problems. To me, the moon is an afterthought on the road to true colonization of the solar system.

Last edited by Oldfart1939 (2017-10-06 09:51:18)

Offline

Like button can go here

#12 2017-10-04 08:55:53

- Oldfart1939

- Member

- Registered: 2016-11-26

- Posts: 2,489

Re: SpaceX's new plan to get to Mars BFR comparison and summary

This new design proposal looks remarkably similar to the earlier Falcon XX; skipping over the Falcon X may be another strategy error IMHO. He needs to progress in a more stepwise manner and do a proof of concept first. Can you say "Falcon X?"

Offline

Like button can go here

#13 2017-10-04 09:29:21

- Antius

- Member

- From: Cumbria, UK

- Registered: 2007-05-22

- Posts: 1,003

Re: SpaceX's new plan to get to Mars BFR comparison and summary

I'm a Luna-first person. Particularly given the water ice that we've detected. We need propellent depots anyway if we're going to launch the big missions, so why haul all the propellent up a steep gravity well when you can mine it on our moon?

The way I see space settlement being for the next several decades is similar to Antarctica and the high seas. There won't be any permanent colonies (unless Mars turns out to be trivial to proteroform...), but there will be thousands of people on Luna and Mars, and maybe other locations, working at science outposts (as in Antarctica), mining camps (like oil rigs), or hotels (akin to cruise ships). If we're lucky, these will lay the groundwork for homesteads and cities to be built.

Of the two worlds (Mars and Luna), I think Luna has the best near-future profitability, due to it's proximity. It has (some) water and minerals which could be mined. It's a useful place for a science base, for example radio astronomy on the farside, as well as studying the moon itself. It's close enough that tourists could visit. Launch windows aren't the problem they are for Mars. Solar power is far more plentiful at the poles. By focusing on Luna first, we can build up an infrastructure that will make it easier to get science bases going on Mars, as well as support the exploration and exploitation of near earth asteroids.

My thoughts exactly, Terraformer. I think Musk's plans for a Martian city are premature and highly problematic. A lot of people are caught up in the excitement of the prospect, without seeing it for what it really is.

It will cost at the very least $1000/kg to ship anything to the Martian surface and an equivalent amount of money to export anything back to Earth. That is the mother of all tariff walls. It effectively cuts the colonists off from all of the luxuries and manufactured goods that we enjoy here on Earth, unless they can make them for themselves. People paying up to a million dollars for a ticket, will find themselves living a meagre existence as troglodytes in cold, dark tunnels that they cannot escape from. Growing enough food is going to be tough. Living standards will be basic for a long time. Maybe it could be made to work at some level, but the novelty will wear off very quickly when the colonists realise that their brave new world is Antarctica without air, where not a single living thing can survive without an artificial environment. Depression and suicide are going to be big problems. Not somewhere I would want to take my family.

I think a moon base is more valuable because it is more than just an end in itself. It can export materials to Earth orbit, where space manufacturing and real colonisation can begin. The big advantage in my mind is that orbital industries can export products to buyers on Earth, whether they are space hotels, solar power satellites or even manufactured goods to Earth surface, in a way that a Martian colony would find much more difficult. This means that colonists on the moon and in high Earth orbit can afford to pay for the things that they need to import. The inability of a Mars colony to do this is what will ultimately kill the Musk dream.

Offline

Like button can go here

#14 2017-10-04 15:01:22

- louis

- Member

- From: UK

- Registered: 2008-03-24

- Posts: 7,208

Re: SpaceX's new plan to get to Mars BFR comparison and summary

Quite - I agree. And with the Moon being so close - 4 days away - I think Space X will hardly bother looking for water when they land their BFR. They will simply take the water with them as part of their 150 tonne allowance and then probably recycle 90% of it within their Lunar Hotel. Musk always looks for the simple and sensible approach. I think he will milk the Moon for tourist money.

We really DON'T know how much water is on the moon, and it could be a very scarce but valuable resource. Principally, it should be used for a moon base, and not squandered. The moon base should have first rights to any lunar ice deposits in order to maintain that colony/base of operations. Manufacturing rocket fuel requires enormous amounts of feedstock for a energy consumptive process. A moon base will be consuming both Oxygen and water. Using liquid H2 as a fuel is fraught with problems. To me, the moon is an afterthought on the road to true colonization of the solar system.

Let's Go to Mars...Google on: Fast Track to Mars blogspot.com

Offline

Like button can go here

#15 2017-10-04 19:29:33

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,397

Re: SpaceX's new plan to get to Mars BFR comparison and summary

Lunar plans:

The BFR would go with less tonnage to make it possible to land and return on the preloaded fuels that will not require any fuels from the moon to be made. Then again the tonnage that it could take could be put into an auxilary tanks for use for that or any other use.

BFR is 106 meters tall and has a total payload capacity of 150 tons whereas the Falcon Heavy at 70 meters tall will only be able to carry 30 tons into lower Earth orbit. The BFR will have more payload capability at 150 tons than even the Saturn V, which took people to the Moon in 1969, Saturn V could only carry 135 tons. On its missions to Mars, the ship will have 40 cabins, not seats. Musk estimates the ideal configuration to be 2 people per cabin, but you could squeeze up to 5 or 6, in addition to that there will be a central storage galley, restaurant, and a solar storm shelter. The oxygen tank on the BFR ship will hold 860 tons of liquid oxygen.

Mars Mission planned archetecture:

Offline

Like button can go here

#16 2017-10-05 20:13:08

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,397

Re: SpaceX's new plan to get to Mars BFR comparison and summary

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Falcon_9 compared to https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saturn_I as compared to the BFR

So If Nasa knew back then how to make the saturn I reuseable as the Falcon 9 has shown what would have we been able to do with that.. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SpaceX_re … nt_program

So is there the thought of returning the BFR from orbit back to earth and then refurbing it after the complete mission to mars for humans?

Offline

Like button can go here

#17 2017-10-06 15:48:11

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,397

Re: SpaceX's new plan to get to Mars BFR comparison and summary

Cargo vs human means while the core design is the same the internal requirements of what is in or out for both means different second stage rockets that wiuld be desinged around the needed specifications of payload to orbit maximized for 150mt....

That said on a first mission that if the human ship can not return back to orbit the crew is stranded until help arrives or they make use of parts from the cargo landers.....

Offline

Like button can go here

#18 2017-10-06 18:45:05

- louis

- Member

- From: UK

- Registered: 2008-03-24

- Posts: 7,208

Re: SpaceX's new plan to get to Mars BFR comparison and summary

Just a thought - if you're landing 300 tonnes you could probably land a few tonnes to make a small ascent vehicle which could join up with a BFR circling in LMO. That would require another BFR to be in LMO but is that such a big deal if they are all reusable?

Cargo vs human means while the core design is the same the internal requirements of what is in or out for both means different second stage rockets that wiuld be desinged around the needed specifications of payload to orbit maximized for 150mt....

That said on a first mission that if the human ship can not return back to orbit the crew is stranded until help arrives or they make use of parts from the cargo landers.....

Let's Go to Mars...Google on: Fast Track to Mars blogspot.com

Offline

Like button can go here

#19 2017-10-07 03:32:00

- elderflower

- Member

- Registered: 2016-06-19

- Posts: 1,262

Re: SpaceX's new plan to get to Mars BFR comparison and summary

But return fuel comes from Mars, Louis. After parking the BFR in LMO it won't have enough fuel for a return, unless it's outward payload is reduced (that is the return fuel becomes part of the payload), as I understand it.

Having said that. Dr Johnson's proposal for multiple excursions from orbit looks seriously doable using a BFR carrying a couple of landers and a lot of fuel.

Offline

Like button can go here

#20 2017-10-07 06:32:53

- louis

- Member

- From: UK

- Registered: 2008-03-24

- Posts: 7,208

Re: SpaceX's new plan to get to Mars BFR comparison and summary

Whoops,yes you are probably right... but how much fuel/propellant does it need to get from LMO to LEO out of interest. Or put it another way, how much does it burn in a propulsive landing on Mars, because that would be available for a return flight to LEO.

But return fuel comes from Mars, Louis. After parking the BFR in LMO it won't have enough fuel for a return, unless it's outward payload is reduced (that is the return fuel becomes part of the payload), as I understand it.

Having said that. Dr Johnson's proposal for multiple excursions from orbit looks seriously doable using a BFR carrying a couple of landers and a lot of fuel.

Let's Go to Mars...Google on: Fast Track to Mars blogspot.com

Offline

Like button can go here

#21 2017-10-07 08:11:44

- GW Johnson

- Member

- From: McGregor, Texas USA

- Registered: 2011-12-04

- Posts: 6,136

- Website

Re: SpaceX's new plan to get to Mars BFR comparison and summary

Whether you come in direct from an interplanetary trajectory at around 5-7 km/s, or from low Mars orbit at about 3.6 km/s makes no difference ultimately. You will come out of aerobraking-hypersonics at roughly 0.7 km/s flight speed, roughly Mach 3 at Martian conditions. The higher entry speeds require shallower angles, and you need hypersonic lift to keep the trajectory from steepening due to gravity.

Now, that end-of-hypersonics speed is what you must kill before you smack the ground, with gravity pulling at you trying to speed you up. It (0.7 km/s) is a theoretical minimum delta-vee to land propulsively.

In practice, the higher you are when you come out of hypersonics, the more "hover budget" you need to fight gravity over time as you land. But, your timelines to land are longer (more amenable to human piloting), and your required decelerations are lower. Delta-vee to land propulsively might be as high as 1.5 km/s and as low as 0.8 or 0.9 km/s.

Note that in landing, most of the delta-vee comes from aerobraking: 3.6 to 7 km/s at entry versus 0.7 km/s at end-of-hypersonics.

That is not the case for ascent. To make low Mars orbit from the surface requires 3.6 km/s orbital speed, plus a little bit more to cover gravity losses and aerodynamic drag. Those losses are smaller than we experience on Earth, but they are still there. Call it 3.8-ish km/sec to achieve low Mars orbit, 4 km/s worst-case (some plane change during ascent).

From low Mars orbit, the min escape speed is 5 km sec, and an appropriate trajectory might require closer to 6-7 km/s final velocity with respect to Mars. Figure your leave-Mars-orbit delta vee from that. Could be as little as 1.5-ish km/s or as high as 3.5-ish km/s, depending upon what you are trying to do on the way home.

Now, Musk's ITS craft has shrunk some since Guadalajara: it was 1900 tons propellant, now something smaller. I dunno, maybe 1200 tons? But the cargo capacity is around 100-150 tons max. So cargo capacity CANNOT be return propellant, by about an order of magnitude! THAT is why Musk insists on producing propellant on Mars, and in turn, THAT is why he makes direct landings instead of staging out of low Mars orbit. His implied thinking-box limitation is that only the ITS goes to Mars. That box limits him to one site.

My Mars mission design over at "exrocketman" uses a different thinking-box limitation. I don't mind using electric propulsion to efficiently send return propellant ahead to low Mars orbit as an unmanned item. I made my lander a separate craft from my manned orbit-to-orbit transport. Landers plus their propellant supplies also get sent efficiently ahead to low Mars orbit unmanned with electric propulsion. Only the manned orbit-to-orbit transport flies there fast with conventional rocketry (using electrics exposes the crew to a fatal dose of Van Allen belt radiation). See the different thinking boxes? My way allows exploration of multiple sites in the one trip, more like what "they" had in mind in the 1950's.

GW

Last edited by GW Johnson (2017-10-07 08:17:04)

GW Johnson

McGregor, Texas

"There is nothing as expensive as a dead crew, especially one dead from a bad management decision"

Offline

Like button can go here

#22 2017-10-07 19:16:10

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,397

Re: SpaceX's new plan to get to Mars BFR comparison and summary

If space x Dragon is to show how we are to compare cargo payload it would be bound by the simular applications of materials and design. http://www.spacex.com/dragon [6]

Dimensions

Height 6.1 metres (20 ft)[4]

Diameter 3.7 metres (12 ft)[4]

Sidewall angle 15 degrees

Volume 10 m3 (350 cu ft) pressurized[5]

14 m3 (490 cu ft) unpressurized[5]

34 m3 (1,200 cu ft) unpressurized with extended trunk[5]

Dry mass 4,200 kg (9,300 lb)[4]

Payload to ISS 6,000 kg (13,000 lb), which can be all pressurized, all unpressurized or anywhere between. It can return to Earth 3,500 kg (7,700 lb), which can be all unpressurized disposal mass or up to 3,000 kg (6,600 lb) of return pressurized cargo[6]

Miscellaneous

Endurance 1 week to 2 years[5]

Re-entry at 3.5 Gs[7][8]

Propellant NTO / MMH[9]

Scale to fit what would ride on the second stage until you get to that magical payload number and multiply out that factor by the following demensions and derive the volume that we can expect Space x to target. Now that you have the scaling factor use it for both of the first and second stages as well keep in mind that we will need to change the diameter in order to keep the size of the craft small.

https://www.science.co.il/formula/

Sure looking at changing materials to shrink mass numbers will help but not at the cost of life as cutting edge will cause cost to rise.

Now lets work in the launcher side of this from the scaling of a falcon 9 which is where he is starting...

http://www.spacex.com/falcon9

Then again we are getting fuzzy numbers to make use of as the page indicate something different for payload numbers.

http://www.spacex.com/sites/spacex/file … ev_2.0.pdf

Once you start to look at the engine count via scaling thats when we get scared as it really means new engines need to be designed to get count down.

Falcon 9 sample flight timeline—

LEO mission Mission Elapsed Time Event

T –3 s Engine start sequence

T + 0 Liftoff

T + 82 s Maximum dynamic pressure (max Q)

T + 170 s Main engine cutoff

T + 175 s Stage separation

T + 180 s (3.0 minutes) Second-engine start-1 (SES-1)

T + 220 s (3.7 minutes) Fairing deploy

T + 540 s (9.0 minutes) Second-engine cutoff-1 (SECO-1)

T + 600 s (10.0 minutes) Spacecraft separation

or this one for recovery:

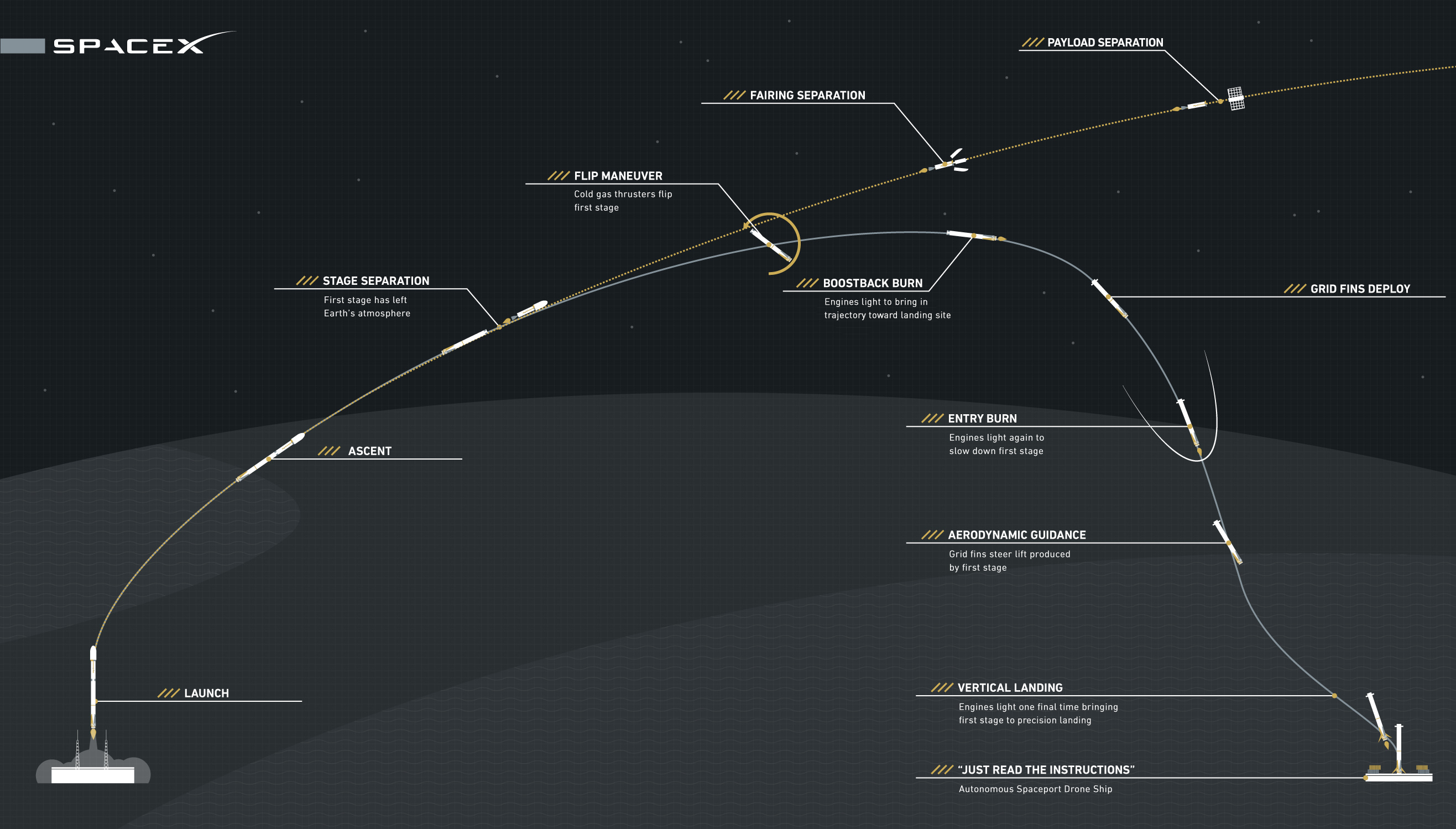

After the first stage main engine cutoff, cold gas N2 thrusters are used to rotate the booster into the direction of flight, they reignite 3 of the Merlin 1D engines. (With 9 in the Octaweb alignment, the center and two on either side of it allow a 'line' of engines to fire).

They use this to kill forward momentum. They continue arcing upwards (since vertical and horizontal momentum components are independent) until they start falling down again.

They then fire three Merlin 1D engines to control descent through the hypersonic regime as they hit thick enough atmosphere to be problematic.

Finally they use the hypersonic grid fins at the top of the upper stage, the cold gas N2 thrusters in combination to try and steer the booster to its target. Time will tell if they have sufficient control to hit a small target that's 300 feet long by 170 feet wide (91 by 52 meters) precisely enough for Falcon 9's leg span of about 70 feet (21 meters).

Once they approach their landing surface, in the last few seconds (10-30 seconds?) they re-ignite the central Merlin 1D to decelerate from terminal velocity to a landing. Hopefully down to 4.5 mph (7.2 km/h) at the time of touchdown, a number that was mentioned during the recent CRS-5 pre-launch news conference. If not, bad things happen.

Offline

Like button can go here

#23 2017-10-08 05:22:02

- elderflower

- Member

- Registered: 2016-06-19

- Posts: 1,262

Re: SpaceX's new plan to get to Mars BFR comparison and summary

Musk is already going to refuel in LEO. Refuelling in LMO should be possible using same techniques. He would need to supply only enough fuel to get GWs return mission out of LMO onto a return trajectory with adjustment allowance to achieve re-entry and propulsive landing on Earth. Return cargo would not need to mass 150 t with a group of say 12 astronauts. Landers would be left behind and 1/2 of the stores would have been used by the time the return window comes around.

Offline

Like button can go here

#24 2017-10-08 09:30:55

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,397

Re: SpaceX's new plan to get to Mars BFR comparison and summary

I am thinking that if we are using 2 BFR cargo that 1 of those could be the landed return to orbit fuel for the crews BFR lander and no seperate small landers that only the crew BFR lands and is refueled by the cargo unit leaving 1 cargo lander for the crew to set up shop on mars with.

So I guess the real question is how much fuel remains in the BFR second stage after Earth departure remains for a mars retro propulsion landing or is the BFR 150 payload a mars crew lander.....

Offline

Like button can go here

#25 2017-10-08 13:28:17

- elderflower

- Member

- Registered: 2016-06-19

- Posts: 1,262

Re: SpaceX's new plan to get to Mars BFR comparison and summary

If Musk depends on ISRU fuel for the return and that fuel is methane he will have to find a source of hydrogen. It doesn't seem likely he will be able to ship so much of it that he can make his methane using imported hydrogen due to continual boil off from a very large tank. That being the case he has to land where there is exploitable water. Until there is an exploration effort on the surface, we don't know where that might be. We should be looking at a number of candidate landing zones to determine which is the best.

If one of his 150te payloads is a tank full of methane and that is sufficient to get a ship home he can refuel on the surface. It is relatively easy to reduce CO2 to CO and liquefy the resulting oxygen, so then he wouldn't depend on finding good water and could land most anywhere, but he will not get his tanker and cargo ships back without a hydrogen source.

Offline

Like button can go here