New Mars Forums

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

Announcement

#51 2014-01-01 11:35:48

- RobertDyck

- Moderator

- From: Winnipeg, Canada

- Registered: 2002-08-20

- Posts: 8,327

- Website

Re: VASIMR - Solar Powered?

Glass density is 2400-2800 kg/m^3. I don't know what they use, but crown glass is said to be 2500 kg/m^3. One mil is 0.0254 mm, so 3 mil thickness is 0.19 kg/m^2. Add that to Emcore's 0.84 kg/m^2, you get 1.03 kg/m^2. So not a big difference, but a little more power and a little lighter.

Offline

Like button can go here

#52 2014-01-02 12:11:18

Re: VASIMR - Solar Powered?

...

The developer for VASIMR claimed it could produce 9,000 seconds Isp with liquid hydrogen. This was after the Glenn Research Centre already achieved 8,400 seconds with a MagnetoPlasmaDynamic thruster, and Russians achieved the same with their largest Thruster Anode Layer Hall Thrusters. So the claim for VASIMR is 9,000 seconds; that sounds like he pulled a number out of thin air just to claim he can do better than his competition. Is this credible? No VASIMR thruster has so far worked with liquid hydrogen, only with xenon, and that one achieved 5,400 seconds. Impressive, but not as good as Glenn's MPD or Russia's TAL Hall. And these others don't use magnetic confinement, so they consume a lot less electrical power. One design feature of VASIMR is adjustable configuration: low thrust / high Isp, or high thrust / low Isp. Call it high gear or low gear. It's actually achieved by adjusting the magnetic nozzle at the exit of the magnetic vacuum bottle. Nice trick, MPD and TAL Hall cannot do that, they have fixed thrust and Isp, they are either fully on or fully off. "Throttle" is achieved by pulsing the thruster. But VASIMR claims it is fully throttleable, and has this "gear" capability. Nice claim, but at what cost? The power requirement is very significant....

Thanks for that info. Another problem with VASIMR is its very poor thrust weight ratio. I estimate it from data released as in the range of 1 to 4,000. So a VASIMR engine putting out 100 N of thrust might weigh 40,000 kg, just in the engine. In contrast the Glenn MPD thruster has a thrust weight in the range of 1 to 200, so 100 N could be done by a 2,000 kg engine.

Bob Clark

Old Space rule of acquisition (with a nod to Star Trek - the Next Generation):

“Anything worth doing is worth doing for a billion dollars.”

Offline

Like button can go here

#53 2014-01-07 14:31:31

Re: VASIMR - Solar Powered?

Robert Zubrin wrote a critique of VASIMR propulsion here:

The VASIMR Hoax

By Robert Zubrin | Jul. 13, 2011

http://www.spacenews.com/article/vasimr-hoax

The primary criticism is that it would require unrealistically lightweight nuclear propulsion. However, Zubrin doesn't even like the idea of fast propulsion to allow short travel times to Mars. He argues in favor of using 6 month or more one-way travel times to allow free return trajectories at Mars. But the health disadvantages of long travel times such as radiation exposure, bone and muscle loss, and the recently found eye damage and vision loss suggest we should investigate such short travel times.

...

So it is important to note we may have a short term power source instead of nuclear power, for plasma propulsion such as Vasimr at the needed lightweight.

The key point is that the power source does not need to be nuclear. According to Zubrin's article on the Vasimr it requires a power source of 1,000 watts per kg power density. This is 100 times better than what has been done with nuclear space power at 10 watts per kg. However, it is only 10 times better than standard solar space cells at 100 watts per kg. Actually more recent space solar cells get 200 watts per kg, so it is only needs to be 5 times better than those.

Now the key fact is that solar cells can put out more power if they have more concentrated light shone on them. Estimates of how much power solar cellls put out are based on the solar insolation at the Earth's distance from the Sun. But if that light is concentrated they can put out more power. In fact some Earth solar power systems get more power by using inexpensive mirrors or lenses to concentrate light over a larger area rather than using expensive solar cells over that larger area.

...

Gossamer sail set to deorbit satellites.

By Jenny Winder | 30 December 2013

http://www.sen.com/news/gossamer-sail-s … satellites

This solar sail has 25 square meters at only 2 kg weight. Let's suppose we only need 10 times solar concentration. This should already be within the capacity of currently used solar cells to accommodate since recent research is in the 100's to 1,000's of Suns range.

At 10 times solar concentration this means the solar cells have 2.5 square meters area in order for the mirror reflecting area to be 10 times greater. If they were 100% efficient this would be 2500 watts of power under standard solar illumination, i.e., without concentration. Solar cells though typically are only in the range of 30% efficient. So they would give 750 watts under standard solar illumination. At a 200 watts per kg power density now reached for space solar cells they would weigh 3.75 kg.

Now we are assuming the sail concentrates 10 times greater surface area onto the cells, so under this concentrated illumination they will put out 7,500 watts. The total weight of the cells and sail would be 5.75 kg. And the power to weight efficiency would be 1,300 watts per kg, sufficient for the Vasimr.

Bob Clark

Last edited by RGClark (2014-01-10 10:40:22)

Old Space rule of acquisition (with a nod to Star Trek - the Next Generation):

“Anything worth doing is worth doing for a billion dollars.”

Offline

Like button can go here

#54 2014-03-16 10:26:41

Re: VASIMR - Solar Powered?

Recent advances in solar concentrators mean we can use solar power rather than nuclear power to power plasma engines. Then we already have the capability to make manned flights to Mars at travels times of weeks rather than months:

Short travel times to Mars now possible through plasma propulsion.

http://exoscientist.blogspot.com/2014/0 … sible.html

Bob Clark

Last edited by RGClark (2014-03-20 04:46:26)

Old Space rule of acquisition (with a nod to Star Trek - the Next Generation):

“Anything worth doing is worth doing for a billion dollars.”

Offline

Like button can go here

#55 2014-03-25 10:09:10

- GW Johnson

- Member

- From: McGregor, Texas USA

- Registered: 2011-12-04

- Posts: 6,114

- Website

Re: VASIMR - Solar Powered?

Bob:

What about combining solar-electric with conventional propulsion? Do the main burns conventional to leave orbit. Then apply solar-electric during the transfer, to vastly shorten travel time? Might that be the best way to avoid the slow spiral-out problem?

GW

GW Johnson

McGregor, Texas

"There is nothing as expensive as a dead crew, especially one dead from a bad management decision"

Offline

Like button can go here

#56 2014-03-25 16:21:53

- Quaoar

- Member

- Registered: 2013-12-13

- Posts: 665

Re: VASIMR - Solar Powered?

Bob:

What about combining solar-electric with conventional propulsion? Do the main burns conventional to leave orbit. Then apply solar-electric during the transfer, to vastly shorten travel time? Might that be the best way to avoid the slow spiral-out problem?

GW

Something like this?

Offline

Like button can go here

#57 2014-03-28 10:03:21

- GW Johnson

- Member

- From: McGregor, Texas USA

- Registered: 2011-12-04

- Posts: 6,114

- Website

Re: VASIMR - Solar Powered?

I'm not familiar with the M2P2 concept, myself. I had in mind either ion or plasma jet thrusters, combined with the lighter-weight solar power being discussed here. Although, this M2P2 thing is another candidate.

The biggest problem with any of the electric schemes is super-low vehicle acceleration. It takes "forever" to leave a parking orbit for a transfer orbit, and the gravity losses associated with the very long burn times are enormous.

So why not do the burn from parking orbit to transfer orbit impulsively with chemical rocket, and then shorten the transfer by using the electric to accelerate on the transfer to its midpoint? Then decelerate electrically the same way during the second half of the transfer.

There's still gravity losses with the electrics, but, at least the transit time is much shorter. Your vehicle will size out somewhere in between the big all-chemical system and the small all-electric system.

Reductions in both size and transit time. Is that not the win-win that we all want?

GW

Last edited by GW Johnson (2014-03-28 10:05:11)

GW Johnson

McGregor, Texas

"There is nothing as expensive as a dead crew, especially one dead from a bad management decision"

Offline

Like button can go here

#58 2014-03-29 04:55:10

- Quaoar

- Member

- Registered: 2013-12-13

- Posts: 665

Re: VASIMR - Solar Powered?

I'm not familiar with the M2P2 concept, myself. I had in mind either ion or plasma jet thrusters, combined with the lighter-weight solar power being discussed here. Although, this M2P2 thing is another candidate.

The biggest problem with any of the electric schemes is super-low vehicle acceleration. It takes "forever" to leave a parking orbit for a transfer orbit, and the gravity losses associated with the very long burn times are enormous.

So why not do the burn from parking orbit to transfer orbit impulsively with chemical rocket, and then shorten the transfer by using the electric to accelerate on the transfer to its midpoint? Then decelerate electrically the same way during the second half of the transfer.

There's still gravity losses with the electrics, but, at least the transit time is much shorter. Your vehicle will size out somewhere in between the big all-chemical system and the small all-electric system.

Reductions in both size and transit time. Is that not the win-win that we all want?

GW

A chemical-electric hybrid looks very promising, but wich kind of electric propulsion has to be choose?

1) VASIMR has the vantage of using cheep argon and the disadvantage to be too massive

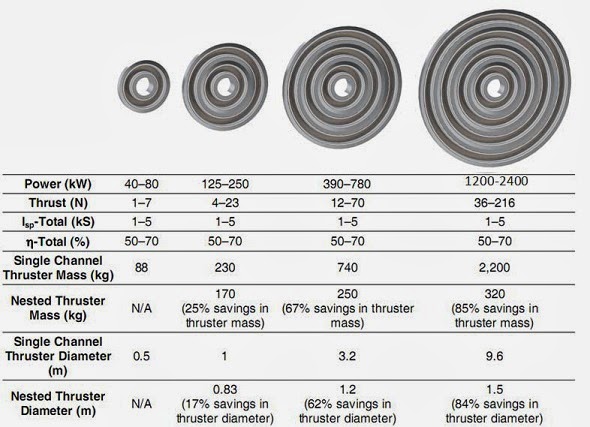

2) Nested Hall effect thruster has the vantage of higher T/W ratio and the disadvantage of using very expensive xenon

3) M2p2 has the vantages of very high T/W ratio (almost 1 N/KW); to function with any kind of propellant from water to hydrazine; and to be used also as a cosmic ray shielding; and the disadvantage to be never tested.

Last edited by Quaoar (2014-03-29 04:58:49)

Offline

Like button can go here

#59 2014-03-29 08:37:55

- GW Johnson

- Member

- From: McGregor, Texas USA

- Registered: 2011-12-04

- Posts: 6,114

- Website

Re: VASIMR - Solar Powered?

My criterion for success in a vehicle hardware program where you intend to fly, is never to incorporate any new technology development as part of your program, use only off-the-shelf (mature) technology. The statistical history is that you never fly unless you avoid developing new technology in your program.

That being said, the electric propulsion that is flying right now is Hall effect, so use that as your baseline. Replace it with VASIMR or something similar, as soon as it is mature. If M2P2 matures in time, then use that. Design your system so that any of the 3 could be incorporated (a VERY important consideration too often ignored).

That way, you'll have a flyable vehicle soonest and cheapest, one that incorporates the best electric propulsion technology that has matured in time to make the trip.

GW

GW Johnson

McGregor, Texas

"There is nothing as expensive as a dead crew, especially one dead from a bad management decision"

Offline

Like button can go here

#60 2014-03-30 10:17:58

- Quaoar

- Member

- Registered: 2013-12-13

- Posts: 665

Re: VASIMR - Solar Powered?

My criterion for success in a vehicle hardware program where you intend to fly, is never to incorporate any new technology development as part of your program, use only off-the-shelf (mature) technology. The statistical history is that you never fly unless you avoid developing new technology in your program.

That being said, the electric propulsion that is flying right now is Hall effect, so use that as your baseline. Replace it with VASIMR or something similar, as soon as it is mature. If M2P2 matures in time, then use that. Design your system so that any of the 3 could be incorporated (a VERY important consideration too often ignored).

That way, you'll have a flyable vehicle soonest and cheapest, one that incorporates the best electric propulsion technology that has matured in time to make the trip.

GW

Here is a nested Hall effect thruster that can use xenon or krypton ( http://pepl.engin.umich.edu/pdf/IEPC-2011-246.pdf ).

Why not posting on your blog, a Mars mission with an hybrid chemical-electric spaceship?

Offline

Like button can go here

#61 2014-03-30 13:05:48

- GW Johnson

- Member

- From: McGregor, Texas USA

- Registered: 2011-12-04

- Posts: 6,114

- Website

Re: VASIMR - Solar Powered?

I'm thinking about it. Too many loose ends still not yet tied up with the Mars Mission 2013 posting.

But employing more than one kind of propulsion is starting to make a great deal of good "gut-feel" common sense.

GW

GW Johnson

McGregor, Texas

"There is nothing as expensive as a dead crew, especially one dead from a bad management decision"

Offline

Like button can go here

#62 2014-04-02 05:28:22

- Quaoar

- Member

- Registered: 2013-12-13

- Posts: 665

Re: VASIMR - Solar Powered?

I'm thinking about it. Too many loose ends still not yet tied up with the Mars Mission 2013 posting.

For example, LOX-LH2 active cooling for your orbital ship and for your landing boat on Mars surface can be considered a mature technology or we have still to do some R&D?

But employing more than one kind of propulsion is starting to make a great deal of good "gut-feel" common sense.

GW

It may be very interesting.

Offline

Like button can go here

#63 2014-04-06 09:59:42

- GW Johnson

- Member

- From: McGregor, Texas USA

- Registered: 2011-12-04

- Posts: 6,114

- Website

Re: VASIMR - Solar Powered?

Quaoar:

I'm not sure that "cryocoolers" suitable for use in space on cryogenic propellant tanks are a "mature" technology or not. Bob Clark or RobertDyck may know more about that. But, I'm pretty sure such a thing could be made ready in a small handful of years; it's not far-future, blue-sky stuff.

I am very intrigued with the notion of accelerating/decelerating along the transfer to cut transit time, using electric propulsion. This would be a dual/hybrid propulsion set-up, like we discussed above, with conventional propulsion doing the impulsive burns at Hohmann transfer delta-vees, at each end of the transfer.

I don't have a good way to estimate how much transit time reduction might be achieved this way. Does anyone have a method of calculating this?

Here's another notion for stable LH2/LOX propellant storage long-term: why not store it as water, even as ice? Just electrolyze what you need for the next burn, with solar electrolysis along the way? Does that sound like a feasible thing to do?

I have not run the numbers on power available vs power required for electrolysis, vs transit time between worlds. I don't have much in the way of data to support running the numbers, but some of y'all might. If it were really feasible, then transporting LH2-LOX propellant becomes very easy. You'd only need the cryocoolers on the tanks being filled for the next burn.

Putting all this together might make a LOX-LH2 ship with electric cruise engines really feasible at much-reduced transit times to Mars. A true "average" Hohmann transfer is about 8 months one-way. If that could be cut to two months, imagine the possibilities!

GW

GW Johnson

McGregor, Texas

"There is nothing as expensive as a dead crew, especially one dead from a bad management decision"

Offline

Like button can go here

#64 2014-04-06 10:34:04

- Terraformer

- Member

- From: The Fortunate Isles

- Registered: 2007-08-27

- Posts: 3,988

- Website

Re: VASIMR - Solar Powered?

You can already cut the transfer time down to 3 months using Lunar fuel at L1...

Use what is abundant and build to last

Offline

Like button can go here

#65 2014-04-06 11:16:54

- Quaoar

- Member

- Registered: 2013-12-13

- Posts: 665

Re: VASIMR - Solar Powered?

Quaoar:

I'm not sure that "cryocoolers" suitable for use in space on cryogenic propellant tanks are a "mature" technology or not. Bob Clark or RobertDyck may know more about that. But, I'm pretty sure such a thing could be made ready in a small handful of years; it's not far-future, blue-sky stuff.

I am very intrigued with the notion of accelerating/decelerating along the transfer to cut transit time, using electric propulsion. This would be a dual/hybrid propulsion set-up, like we discussed above, with conventional propulsion doing the impulsive burns at Hohmann transfer delta-vees, at each end of the transfer.

I don't have a good way to estimate how much transit time reduction might be achieved this way. Does anyone have a method of calculating this?

Here's another notion for stable LH2/LOX propellant storage long-term: why not store it as water, even as ice? Just electrolyze what you need for the next burn, with solar electrolysis along the way? Does that sound like a feasible thing to do?

Producing LOX-LH2 from water will result an O/F ratio of 9 that is a bit higher, but if you use a tripropellant rocket like RD-701 (LOX-RP1-LH2) it may be work vewry well: we can store only water and kerosene, with the tanks that surround the habitat, resulting a very good cosmic ray shielding: with 50 g/m2 of water and kerosene around the habitat, astronauts will take only 35 REM/year at solar minimum and near 13 REM at solar maximum ( http://www.cs.odu.edu/~mln/ltrs-pdfs/NASA-97-tp3682.pdf - kerosene and water have almost the same shielding power of polyethylene).

An RD-701 like rocket has a very high thrust with an exaust velocity of 4 km/s that is still very good.

RD-171 was projected to work with 79% LOX; 15% kerosene; 6% LH2: to be optimized for using LOX and LH2 from water the newer version will be function with an higher percent of LH2 (something like 77.6% LOX; 13.8 % RP-1 and 8.6% LH2) resulting an higher exaust velocity (4.2 km/s?).

Last edited by Quaoar (2014-04-06 13:20:41)

Offline

Like button can go here

#66 2014-04-07 09:47:39

- GW Johnson

- Member

- From: McGregor, Texas USA

- Registered: 2011-12-04

- Posts: 6,114

- Website

Re: VASIMR - Solar Powered?

How about splitting the water at 9:1 oxygen:hydrogen, then diverting some of the oxygen to life support. That plus a little kerosene would get better propellant ratios, perhaps, for a tripropellant engine.

GW

GW Johnson

McGregor, Texas

"There is nothing as expensive as a dead crew, especially one dead from a bad management decision"

Offline

Like button can go here

#67 2014-04-07 14:45:19

- Quaoar

- Member

- Registered: 2013-12-13

- Posts: 665

Re: VASIMR - Solar Powered?

How about splitting the water at 9:1 oxygen:hydrogen, then diverting some of the oxygen to life support. That plus a little kerosene would get better propellant ratios, perhaps, for a tripropellant engine.

GW

It may be better, but water electrolisys will produce 5.4 Kg/Kw per day of oxygen and hydrogen, so a spaceship with 20-30 KW of solar panels will produce 19.4-29.4 tons of propellant in 180 days, that may not be enough for a 4-4.5 km/s delta-V of Earth orbital inserction if the ship is quite massive like your projects. Propellant production can be done in Mars orbit but it will take almost the woole lenght of the surface Mission, so it may be better to store LOX and LH2 with a good active cooling system. Even in this case, a LOX-RP1-LH2 tripropellant rocket may be a good option because it has a good exaust velocity and LH2 is only 6% of the whoole propellant mass, resulting less tankage and cooling power.

Another option may be to mount very big solar arrays or one or two 100 KW SAFE-400 nuclear reactor: in this case we can store water and produce 45-90 tons of propellant in almost 100 days.

Last edited by Quaoar (2014-04-07 14:53:34)

Offline

Like button can go here

#68 2014-04-07 17:33:10

- GW Johnson

- Member

- From: McGregor, Texas USA

- Registered: 2011-12-04

- Posts: 6,114

- Website

Re: VASIMR - Solar Powered?

I've got no numbers, but somehow this tripropellant scheme should work. I really like how easy it is to ship water-as-ice. Kerosene is not much harder to ship. Makes good practical sense to me. Especially if you are not flying very fast, so that electrolysis rates are not required to be very high.

But, if you add solar electric propulsion and fly much faster, the production rate problem requires a really good solution. It's a bit outside my areas of expertise to suggest that we have such a solution. But, I'd bet someone out there does know.

GW

GW Johnson

McGregor, Texas

"There is nothing as expensive as a dead crew, especially one dead from a bad management decision"

Offline

Like button can go here

#69 2014-04-08 06:14:46

- Quaoar

- Member

- Registered: 2013-12-13

- Posts: 665

Re: VASIMR - Solar Powered?

On second thought, GW's idea, of storing water and electrolyze it, seems fantastic: LOX-LH2 rockets, working with a perfect stoichiometric O/F ratio of 8:1 have slightly lower exaust velocity (almost 4.4 km/s instead of 4.6) but I think its very convenient to trade 0.2 km/s for the semplicity of water storage.

Another option may be to use a tripropellant rocket with a more classical LOX/LH2 ratio of 6 and and some RP1 to be bourned with the oxigen in excess (almost 0.8 tons every 9 tons of water for a good LOX/RP-1 ratio of 2.5)

I imagine this kind of ship with a concentric shells water tank sourrounding the habitat, to protect astronauts from GCR and SPE.

The ship will have solar panels for life support and a SAFE-400 100 KW nuclear reactor, completely dedicated to electrolisys, cooling and liquefaction, that can produce almost 500 kg/day of LOX-LH2.

Nuke weight almost 500 kg: I don't know how much weight electrolisys and cooling equipment, but I think it's in the range of 2-4 tons.

To have also electric propulsion, just add another 100 KW SAFE-400.

In this way, we may have a ship that can go and refuel everywhere, just like a water NERVA, but that can be built now with very minimal R&D.

Last edited by Quaoar (2014-04-16 08:29:07)

Offline

Like button can go here

#70 2015-04-02 20:05:09

Re: VASIMR - Solar Powered?

In case anyone is interested, I've finally done a full analysis of the whole "39 days to Mars" thing, and shown it to be conclusively untrue. The full post is on my blog:

https://gammafactor.wordpress.com/2015/ … hang-diaz/

But this is the most important bit:

The maximum allowable mass is normalized to 1, with the mass of the engines and total system masses expressed relative to this. As you can see, they’re much, much higher.

Basically, I calculated the trajectory using MATLAB, and using assumed values for various system masses I calculated how much total mass you need to make an interplanetary VASIMR cruiser happen. Turns out, you need between 12 and 40 times as much mass as it's physically possible to have and still make your mission happen.

-Josh

Offline

Like button can go here

#71 2015-04-03 09:27:59

- GW Johnson

- Member

- From: McGregor, Texas USA

- Registered: 2011-12-04

- Posts: 6,114

- Website

Re: VASIMR - Solar Powered?

Went to your site and read full article. Excellent analysis. Thanks. And congrats!

Yours and my insights coincide: slower cargo trips are an excellent application of SEP (or nuke-electric). For manned, all you can do is perhaps speed up the transits with electric, between impulsive burns at each end. Otherwise, travel times will just be too long for men. There would be little point.

GW

Last edited by GW Johnson (2015-04-03 09:28:39)

GW Johnson

McGregor, Texas

"There is nothing as expensive as a dead crew, especially one dead from a bad management decision"

Offline

Like button can go here

#72 2015-04-03 20:32:16

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,038

Re: VASIMR - Solar Powered?

A starting of 0 km/s is not possible to earth orbit and the same is true for mars both mean we have started on the surface or in geo orbit for earth at start and a 0 km/s at mars means that we are in mars geo orbit or have completed the descent.

The 39 days also does not take into account the time in orbit before starting the engine to send the ship off on its journey nor the wait time in orbit before starting descent.

But you are right half the journey is to speed up while the second half is to slow down. Which means that we are average speed for the distance of approximate 22.26 km/s with the peak of the journey ending at a top speed of 44.3 km/s which makes for day 19.5 on the outward journey. This makes for a delta per day of 2.2 km/s with half the fuel for the journey gone at day 19.5 which means that the fuel is 2.26% of the useage per day.

I notice dry versus wet mass, which is mass fraction for the ship we want to get to mars from earth orbit with an empty fuel take. So if we know the size of the ship remaining at mars orbit you can reverse calculate the fuel mass

and with that value you can now solve for the isp output from the engine that consumes the 2.26% of the available fuel per day.

Offline

Like button can go here

#73 2015-04-04 19:06:58

Re: VASIMR - Solar Powered?

SpaceNut,

The acceleration is not constant over the course of a flight because the engines operate at the same force at all times while the mass decreases. a=F/m, so as m goes down if F stays constant acceleration will increase. So that means it takes less time to decelerate than accelerate. Below, you'll see a graph of what I mean:

Please note that the third plot is the acceleration magnitude of the acceleration and not the acceleration. After the "kink" in the velocity graph the acceleration would be negative because the velocity is decreasing, but I think this is clearer.

That's why you can't use "normal" constant-acceleration kinematics for this problem, because the acceleration isn't constant. What I'm going to do next, I think, is make a program that will output a reasonable trip time for a given exhaust velocity, if I can figure out a good way to do that.

-Josh

Offline

Like button can go here

#74 2015-05-24 10:04:36

Re: VASIMR - Solar Powered?

In case anyone is interested, I've finally done a full analysis of the whole "39 days to Mars" thing, and shown it to be conclusively untrue. The full post is on my blog:

https://gammafactor.wordpress.com/2015/ … hang-diaz/

But this is the most important bit:I wrote:https://gammafactor.files.wordpress.com … masses.jpg

The maximum allowable mass is normalized to 1, with the mass of the engines and total system masses expressed relative to this. As you can see, they’re much, much higher.Basically, I calculated the trajectory using MATLAB, and using assumed values for various system masses I calculated how much total mass you need to make an interplanetary VASIMR cruiser happen. Turns out, you need between 12 and 40 times as much mass as it's physically possible to have and still make your mission happen.

Thanks for those calculations. As you can see from your calculated values, a major problem with the VASIMR is the mass of the engine. You cited the report:

The VASIMR Engine: Project Status and Recent Accomplishments.

AIAA 2004-0149

http://spaceflight.nasa.gov/shuttle/sup … ss2004.pdf

So with the numbers used in this report of 1 megawatt (input) power and weight to power ratio of 1 kg to 1 kW power, the engine masses in this report at ca. 1,000 kg. Then this graph indicates a thrust-to-weight ratio in the range of 1 to 1,000, or perhaps 1 to 500 if using lithium, which they say is not the preferred propellant because of difficulties of handling it.

However, already existing Hall effect thrusters can get thrust-to-weight ratios of 1 to 100:

Developmental Status of a 100-kW Class

Laboratory Nested channel Hall Thruster.

IEPC-2011-246

Table 1, Example of concentrically NHT specific mass and footprint savings, p. 5.

http://pepl.engin.umich.edu/pdf/IEPC-2011-246.pdf

Remember being able to get high thrust is important for this scenario of fast travel time. Otherwise it's the same scenario as with ion propulsion where the travel time would actually be slower than chemical propulsion because of the very small thrust.

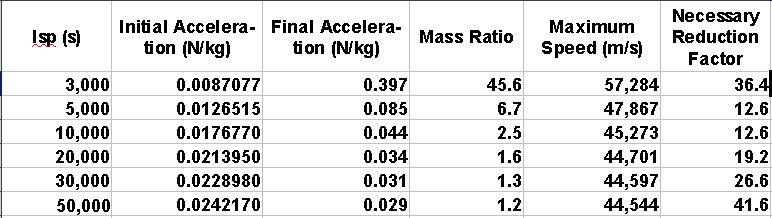

Here are the numbers you are envisioning for your VASIMR vehicle:

The most important number in this chart is the Necessary Reduction Factor (NRF). It describes the ratio of necessary solid mass to the amount of allowable solid mass. For example, if you choose an exhaust velocity such that your rocket has a mass ratio of 4, and its initial mass is 80 tonnes, you can have up to 20 tonnes of solid mass. But let’s say your tanks mass 3 tonnes, your engines mass 17 tonnes, and your power source masses 20 tonnes. That would mean you would need 40 tonnes of solid mass to complete your mission, and you would have a NRF of 40/20=2. Basically, it describes how much you need to shrink down your components to make the mission feasible. For NRFs below 1, you have some amount of payload carrying capability too.

But using Hall effect thrusters you could reduce the calculated weight of 17 tonnes to 1.7 to 3.4 tonnes.

The next problem is the mass of the solar power system. Based on a 300 watt/kg specific power for the solar cells you get a 20 tonne mass for the solar power source. However, I think at least 1,000 watt/kg solar power is possible by using solar concentrators. The reason is the mirrors or lenses would be much lighter than solar cells used so you could get the same power at lighter weight.

So if the solar power sources mass, say, 7 tonnes then you see the case may indeed close for getting the total vehicle dry mass low enough to get the high speed needed, but by using existing Hall effect thrusters, not VASIMR.

Bob Clark

Last edited by RGClark (2015-05-24 10:21:59)

Old Space rule of acquisition (with a nod to Star Trek - the Next Generation):

“Anything worth doing is worth doing for a billion dollars.”

Offline

Like button can go here

#75 2015-05-25 20:32:09

Re: VASIMR - Solar Powered?

RGClark-

Please note that those numbers were given as examples and don't represent real values. The real values can be found in the following table:

I note that these nested hall thrusters are every bit as theoretical as a high power VASIMR thruster, and those numbers don't necessarily represent the mass of any engine that will ever be built.

-Josh

Offline

Like button can go here