New Mars Forums

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

Announcement

#1 Yesterday 19:24:59

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,224

Starship to mars count down 273 days to launch

What can we send to Mars on the first Starships?

By:

Casey Handmer's blog

As of today, it is 601 days until October 17, 2026, when the mass-optimal launch window to Mars opens next.

How many days are there between two dates?

So the actual count down is on 273 days remaining as of todays date 1-17-26

While I don’t have any privileged information, it’s fun to speculate about what SpaceX could choose to send on its first Starship flights to Mars. (Spoiler alert: Rods from the gods…)

Over the next 600 days, SpaceX has a number of key technologies to demonstrate; orbit, reuse, refill, and chill.

Orbit. This Friday we’re due for Flight 8, which may finally achieve orbit. Earlier flights technically had the necessary performance but deliberately targeted the ocean to prevent the possibility of a Starship being stranded in orbit without propulsion capability, and then undergoing an uncontrolled re-entry.

Reuse. The holy grail of rocketry. SpaceX has indicated they may attempt to refly Booster 14 on Flight 9, which would establish booster reuse. Flight 9 may also see the first attempt to catch the Starship upper stage, but in any case the successful reuse of both stages of Starship is necessary to fly to Mars.

Refill. We can load Starship up with cargo for Mars but it’s not going to leave low Earth orbit (LEO) unless Starship can be refilled with fresh fuel and oxidizer. SpaceX has been working on orbital refilling for some time but we need to see it actually working.

Chill. By far the easiest of the four tasks, but long term stability of Starship’s cryogenic fuel will require that it be actively refrigerated, particularly in the challenging thermal environment of LEO or deep space.

It’s hard to make predictions, particularly about the future. I’m optimistic that SpaceX will have multiple fully fueled Starships ready to go in October next year, to be followed by a ten month cruise and then either Mars orbital insertion or an attempted landing. While I’m optimistic about Earth departure I think Starship’s first ever attempted Mars landing falls into the “excitement guaranteed” bucket, and perhaps we shouldn’t pin all our hopes on success the first time.This poses an interesting question about what, if anything, we should ship to Mars at the first opportunity.

In my recent article for Palladium, I summarized eleven key technologies needed to build a Mars base. Some of those are essential from the very beginning, while others are only necessary later on. Some of them are areas where SpaceX already has world-leading expertise, and some of them are areas of active research requiring considerable additional engineering effort. Let’s think about this systematically.

As of 2025, I think industry expertise looks like this. The bolded items are key areas I think SpaceX will need to bring in house to assure success on their timelines, while the italic options may also be useful.

n particular, it seems clear to me that not much can be done at scale on Mars without a synthetic fuel plant – which is part of the reason I’m working on this technology at Terraform Industries. If you need to work on borderline impossible problems with brilliant people, you may like to consider joining us!

Synthetic fuel is easy enough on Earth, but on Mars it depends on several inputs which are non-trivial. Electricity, ambient CO2, and water to source hydrogen. CO2 ingestion is easy enough, it was demonstrated by the MOXIE instrument on the Mars Perseverance rover. Mars power will most likely be provided by large solar arrays on the surface. This is a challenge in terms of mass, since providing enough solar arrays will require multiple Starships of cargo, but Starship’s entire purpose is to schlep mass from Earth to Mars so I think this will be doable.

Water, on the other hand, is non-trivial. We know that Mars has plenty of water. We can even see water ice in satellite photos of prospective landing sites, in the form of glacial features or splosh craters. But there’s a big difference between turning on a tap and obtaining sufficient water from ice. How deep is the ice? How pure is it? Is it full of rocks, sand, gravel, and/or salt? Is it porous or solid? How cold and hard is it? How much do we need? How far from our landing site are sufficient water deposits? How deep might geothermally heated liquid water be?

Water, on the other hand, is non-trivial. We know that Mars has plenty of water. We can even see water ice in satellite photos of prospective landing sites, in the form of glacial features or splosh craters. But there’s a big difference between turning on a tap and obtaining sufficient water from ice. How deep is the ice? How pure is it? Is it full of rocks, sand, gravel, and/or salt? Is it porous or solid? How cold and hard is it? How much do we need? How far from our landing site are sufficient water deposits? How deep might geothermally heated liquid water be?

What could we ship on Starship with a 600 day lead time? JPL has developed some incredible ultraspectral scanning cameras with ~6000 color channels. Hook this to a 2.5 m aperture camera mounted within a Starship that aerobrakes into orbit and we can get precise surface mineralogy at 6 cm resolution. The limitation of this approach is that much of Mars is covered in a thin but optically opaque layer of dust with relatively uniform mineralogical constituents. Still, it’s time to move beyond HiRISE!

Orbital radar

MRO also flew SHARAD, a ground penetrating radar that has helped us map and understand Mars’ ice covering, particularly where it’s obscured by a layer of surface moraine. SHARAD has collected extraordinary data for an orbital radar with a power of just 10 W! What if we used Starship to transport a dozen or so Starlink satellites to Mars, each with a software update to use their powerful phased array antenna as an orbital radar? Because they form a constellation, they could even do multistatic synthetic aperture statistics. We need to build a relay constellation in Mars orbit sooner or later. As a complementary component, we could drop a wideband radio into the orbital Starship to put out far more than 10 W at much lower frequencies, seeing deeper into the crust. We have extremely powerful, versatile, programmable digital radio front-ends these days – and we should be using them to find stuff underground, including more scrolls!As of today, it is 601 days until October 17, 2026, when the mass-optimal launch window to Mars opens next.

While I don’t have any privileged information, it’s fun to speculate about what SpaceX could choose to send on its first Starship flights to Mars. (Spoiler alert: Rods from the gods…)

Over the next 600 days, SpaceX has a number of key technologies to demonstrate; orbit, reuse, refill, and chill.

Orbit. This Friday we’re due for Flight 8, which may finally achieve orbit. Earlier flights technically had the necessary performance but deliberately targeted the ocean to prevent the possibility of a Starship being stranded in orbit without propulsion capability, and then undergoing an uncontrolled re-entry.

Reuse. The holy grail of rocketry. SpaceX has indicated they may attempt to refly Booster 14 on Flight 9, which would establish booster reuse. Flight 9 may also see the first attempt to catch the Starship upper stage, but in any case the successful reuse of both stages of Starship is necessary to fly to Mars.

Refill. We can load Starship up with cargo for Mars but it’s not going to leave low Earth orbit (LEO) unless Starship can be refilled with fresh fuel and oxidizer. SpaceX has been working on orbital refilling for some time but we need to see it actually working.

Chill. By far the easiest of the four tasks, but long term stability of Starship’s cryogenic fuel will require that it be actively refrigerated, particularly in the challenging thermal environment of LEO or deep space.

It’s hard to make predictions, particularly about the future. I’m optimistic that SpaceX will have multiple fully fueled Starships ready to go in October next year, to be followed by a ten month cruise and then either Mars orbital insertion or an attempted landing. While I’m optimistic about Earth departure I think Starship’s first ever attempted Mars landing falls into the “excitement guaranteed” bucket, and perhaps we shouldn’t pin all our hopes on success the first time.This poses an interesting question about what, if anything, we should ship to Mars at the first opportunity.

In my recent article for Palladium, I summarized eleven key technologies needed to build a Mars base. Some of those are essential from the very beginning, while others are only necessary later on. Some of them are areas where SpaceX already has world-leading expertise, and some of them are areas of active research requiring considerable additional engineering effort. Let’s think about this systematically.

As of 2025, I think industry expertise looks like this. The bolded items are key areas I think SpaceX will need to bring in house to assure success on their timelines, while the italic options may also be useful.

Outlook 2025 SpaceX expertise SpaceX non expert

Easier technology Space Solar PV Mars air separation/miner

Water prospector

Pressure structures

Harder technology Starship

Orbital refilling

Cryofuel heat rejection

Mars EDL

Space suits Long duration life support

Surface life support

Water miner

Fuel plant

Rock miners

Construction robots

Nuclear reactor

In particular, it seems clear to me that not much can be done at scale on Mars without a synthetic fuel plant – which is part of the reason I’m working on this technology at Terraform Industries. If you need to work on borderline impossible problems with brilliant people, you may like to consider joining us!Synthetic fuel is easy enough on Earth, but on Mars it depends on several inputs which are non-trivial. Electricity, ambient CO2, and water to source hydrogen. CO2 ingestion is easy enough, it was demonstrated by the MOXIE instrument on the Mars Perseverance rover. Mars power will most likely be provided by large solar arrays on the surface. This is a challenge in terms of mass, since providing enough solar arrays will require multiple Starships of cargo, but Starship’s entire purpose is to schlep mass from Earth to Mars so I think this will be doable.

Water, on the other hand, is non-trivial. We know that Mars has plenty of water. We can even see water ice in satellite photos of prospective landing sites, in the form of glacial features or splosh craters. But there’s a big difference between turning on a tap and obtaining sufficient water from ice. How deep is the ice? How pure is it? Is it full of rocks, sand, gravel, and/or salt? Is it porous or solid? How cold and hard is it? How much do we need? How far from our landing site are sufficient water deposits? How deep might geothermally heated liquid water be?

We just don’t know the answers to these questions, and not for a lack of trying! We know there is water, but the error bars around its composition are large, and that makes engineering a water mining machine really difficult. It’s not impossible, but if we knew just a little bit more about the water situation, we could save a bunch of mass, power, reliability, and engineering effort.

This makes me think that, in addition to testing long duration cruise, systems stability and reliability, and Mars entry, descent and landing, it would be very useful to add instruments to Starship that can shrink the error bars around water for our prospective landing site(s).

Remote water prospector ideas

Starship’s potential as a platform to transport enormous quantities of mass to Mars (and other places) is so extreme we should already be developing next generation science instruments. Some may not be ready by October 2026, but there’s another opportunity in 2028. Early Starships may not succeed, but that’s not a problem if we produce enough instruments to cover for potential losses. This has been obvious enough since 2019, and in an ideal world we’d already have a warehouse full of instruments ready to go.Ultraspectral orbital imager

Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter flies the HiRISE instrument, a 0.5 m aperture scanning camera with a resolution of 0.3 m per pixel, imaging in three color bands. The whole instrument weighs just 65 kg.What could we ship on Starship with a 600 day lead time? JPL has developed some incredible ultraspectral scanning cameras with ~6000 color channels. Hook this to a 2.5 m aperture camera mounted within a Starship that aerobrakes into orbit and we can get precise surface mineralogy at 6 cm resolution. The limitation of this approach is that much of Mars is covered in a thin but optically opaque layer of dust with relatively uniform mineralogical constituents. Still, it’s time to move beyond HiRISE!

Orbital radar

MRO also flew SHARAD, a ground penetrating radar that has helped us map and understand Mars’ ice covering, particularly where it’s obscured by a layer of surface moraine. SHARAD has collected extraordinary data for an orbital radar with a power of just 10 W! What if we used Starship to transport a dozen or so Starlink satellites to Mars, each with a software update to use their powerful phased array antenna as an orbital radar? Because they form a constellation, they could even do multistatic synthetic aperture statistics. We need to build a relay constellation in Mars orbit sooner or later. As a complementary component, we could drop a wideband radio into the orbital Starship to put out far more than 10 W at much lower frequencies, seeing deeper into the crust. We have extremely powerful, versatile, programmable digital radio front-ends these days – and we should be using them to find stuff underground, including more scrolls!Here’s an example of existing orbital datasets for the prospective landing site in the Phlegra Montes. There’s no shortage of ice, but can we easily get it into our distribution system?

Thermal imager

Mars Odyssey flew a thermal imager (THEMIS) to Mars in 2001. Part of its mission was to search for evidence of volcanism or geothermal hydrological activity (such as geysers). While THEMIS collected a global dataset for both night and day conditions, as far as I know no detections or exclusions of active geological surface heat, nor the results of a global survey, have ever been published. We could send a follow up, and far more capable, thermal imager to perform a global survey in the appropriate orbit to find any trace of excess surface heat.Non-remote water prospector ideas

Starship is designed to move 100 tonnes of cargo to Mars, so we’re not limited to larger versions of existing orbital instruments. Let’s explore options for soft-landed surface mass, or not-so-soft-landed surface mass!Surface prospector

A lander, rover, or helicopter(s) could perform direct inspection of surface conditions within a limited area adjacent to landing. For example, a Starship on the surface could literally deploy a drill and see what happens. Honeybee Robotics has developed numerous varieties of water-extracting drills. Why not yolo a few of these and see what happens?Early Starship Mars landing attempts should focus on producing numerous, relatively simple robust robots to a) hedge against potential losses by focusing on production and b) test new materials, processes, and methods that can be fed back into scaled up systems for subsequent exploration.

Rods from the gods

We know there’s a high likelihood mostly pure water ice exists within 10-20 m of the surface across large swaths of the various prospective landing sites. Why not drop off a few dozen long steel (or tungsten) spears, guide them in while tracking them on radar, and then survey their impact craters with HiRISE as soon as the dust has cleared? These rods will impact the surface at about 8 km/s, penetrating many times their length, and exposing the subsurface to our existing orbital instruments for the first time. The main attraction of this approach is that it requires essentially zero additional effort on top of the existing program, whereas the others require either a crash instrument development program, or building and flying multiple intricate surface operations robots and landing them with an extremely untested EDL system. Rods from the gods merely requires dropping a few tonnes of steel in roughly the same area and then surveying the damage. It’s also the only method that can deliver enough energy to actually directly access the deep subsurface at scale.There’s even precedent for dropping chunks of tungsten on Mars. NASA JPL’s rover missions each used eight large tungsten masses totalling 300 kg to alter aerodynamic characteristics of its aeroshell on entry, and their impacts were found with MRO after the fact.

Summary of options

In my opinion, the greatest source of uncertainty for the near term success of a Mars base, beyond Starship transport capability, is sourcing sufficient water. Any kind of industrial activity on Mars will consume water in the thousands, if not millions of tonnes. We don’t want to be constrained by raw material availability, so we have to find some way to produce a torrent of water.There are a number of ways to address this uncertainty in parallel. In terms of cost and risk, the cheapest, easiest, and least risky option is rods from the gods – and it’s also pretty fun. If we’re prepared to spend more money and allocate more engineering effort with a modest increase in risk, we can deploy numerous instruments and additional satellites into Mars orbit.

At the same time, a cost/risk optimal strategy should also allocate a modest portion of the pie to development of soft-landed surface instruments and robots to perform contact science and directly scout prospective landing locations.

Tech outlook 2028

The next next launch window is in November 2028. Starships from the previous one will land in August 2027, leaving us, at most, about 500 days to process data and assimilate results from prospecting and other tech demos on the earlier flight. This cadence will set the pattern for the next couple of decades of development. Proactive development and stockpiling of projected necessities, followed by reactive short term revision of designs and cargo in preparation for consecutive launch windows separated by only 26 months.If all goes well, the technology situation in 2028 could look like this.

SpaceX will have in-housed all the technology that’s intrinsic to successful operation of the Starship fleet, including long duration life support. They will have also taken the lead on buying down risk on key environmental parameters, which are mostly landing site water and mineral abundance.

Remaining for collaborative parties are the relatively easy task of pressure structures, and the harder tasks of developing the fuel plant, rock miners, construction robots, and any nuclear reactors. Now is the time to start work on this essential hardware!

Once these pieces are all in place, the Mars city will have secure access to import shipping capacity and all raw material inputs, as well as a large pressurized and climate controlled volume in which to build. This “terrarium” allows the rest of the industrial stack to be imported from Earth with minimal redesign or customization, limited only by shipping capacity.

The next question

What do we bring when we send people? What do we need to start working on today to ensure it is ready in time? Once we have the Mars city pressure structure and stockpiles of water, various gasses, and mineral ores in place, what needs to be sent up, how much of it, and when?

Offline

Like button can go here

#2 Yesterday 19:26:18

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,224

Re: Starship to mars count down 273 days to launch

Why Elon Musk now says it would be a 'distraction' for SpaceX to go to Mars this year

SpaceX is unlikely to attempt a Mars mission in 2026 after all, according to CEO Elon Musk, marking a setback in his plans to colonize the planet.

“It would be a low-probability shot and somewhat of a distraction,” Musk told entrepreneur Peter Diamandis in a podcast recorded in late December and published this week.

In September 2024, Musk discussed SpaceX’s plans to send an uncrewed Starship rocket to Mars this coming year. At the time, Musk said the mission would test how reliably SpaceX could land its vehicles on the planet’s surface. If things went well, he estimated SpaceX could send crewed missions as soon as 2028.But Musk has dialed back his optimism over the past year. In May, he gave his company a 50% chance of being ready for a launch in late 2026, which would coincide with a narrow window that occurs every two years when Mars and Earth align. A few months later, he said the uncrewed flight would “most likely” happen in 2029.

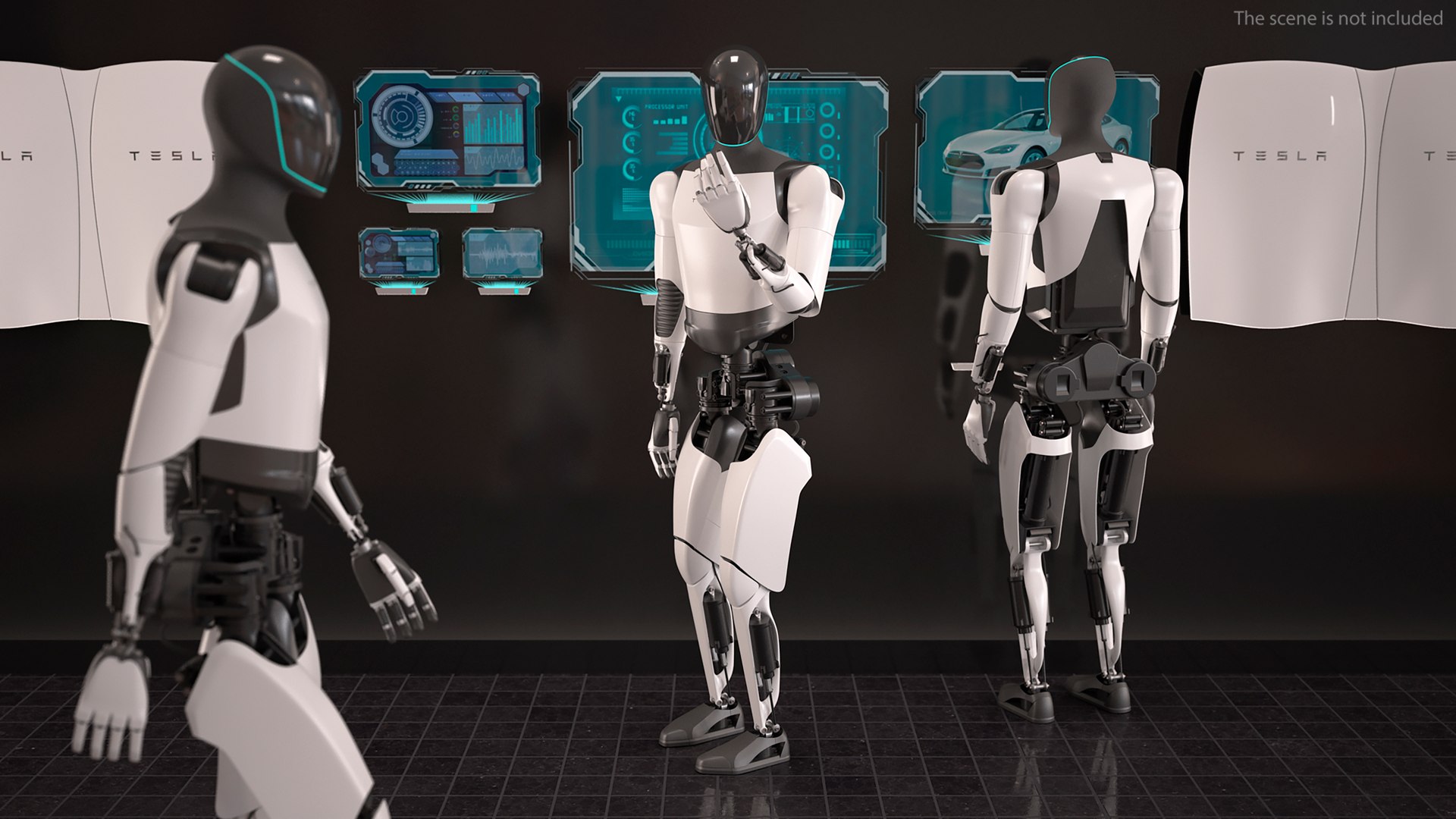

August 2025, Musk said there was a “slight chance” of a Starship flight to Mars in November or December 2026 crewed by Optimus, the humanoid robots being developed by Tesla “A lot needs to go right for that.”

A mission to Mars hinges on SpaceX being capable of refueling Starship’s upper stage in orbit, a complicated task that Musk told Diamandis could be achieved toward the end of 2026. Accomplishing orbital refueling is also crucial for SpaceX to complete a recently reopened contract to carry NASA astronauts to the moon.

SpaceX was on track to demonstrate its process — which involves launching tanker versions of Starship into orbit — in 2025, a NASA official said the year before. But the company missed that target and now plans to attempt its first orbital-refueling demonstration between Starship vehicles in June, according to internal documents viewed by Politico.

SpaceX, which is now developing the third generation of the reusable 404-foot Starship rocket, has also had difficulty testing its vehicle. Its first three flights of 2025 were failures, while the remaining two launch attempts were much more successful. The next iteration of Starship will be a “massive upgrade” over its predecessor, Musk has said.SpaceX was on track to demonstrate its process — which involves launching tanker versions of Starship into orbit — in 2025, a NASA official said the year before. But the company missed that target and now plans to attempt its first orbital-refueling demonstration between Starship vehicles in June, according to internal documents viewed by Politico.

SpaceX, which is now developing the third generation of the reusable 404-foot Starship rocket, has also had difficulty testing its vehicle. Its first three flights of 2025 were failures, while the remaining two launch attempts were much more successful. The next iteration of Starship will be a “massive upgrade” over its predecessor, Musk has said.

In addition to preparing for Mars and lunar missions, SpaceX dominates the commercial launch industry and runs a successful satellite-internet business. It plans to go public later this year in what could be a record-breaking listing that could help fund its plans for Starship as well as for space-based data centers.

Although SpaceX probably won’t be headed to the red planet in 2026, twin spacecraft will make the journey this year. Blue and Gold, a pair of satellites developed by Rocket Lab were launched into space last November by Amazon founder Jeff Bezos’s Blue Origin to fulfill NASA’s Escapade mission.

The spacecraft are expected to attempt a trans-Mars injection engine burn in November 2026 and arrive at the planet in September of next year, according to NASA. The satellites will be operated by the Space Sciences Laboratory at the University of California, Berkeley, and will gather data that could help humans land on or even settle Mars.

This guy might be the first

Offline

Like button can go here