New Mars Forums

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

Announcement

#376 2026-01-07 10:25:35

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 24,123

Re: kbd512 Postings

For kbd512 ...

This post picks up on #375...

I ran a search to see what is offered in topics ... we have nothing for SCO2. We have only one topic with supercritical...

Coal-fired Brayton Cycle Supercritical CO2 Boilers

That topic is probably a candidate for an update...

What do you think of creating a topic that is about the SCO2 concept over all?

Wikipedia has an article that appears to be an attempt to keep up to date.

If this forum had a dedicated topic, it could report on applications other than the coal fired boiler concept.

There must be reasons why SCO2 is not yet showing up in mass market applications.

Perhaps there is something about this technology that requires a massive investment to realize a return, and with existing systems performing reasonably well, perhaps investors simply aren't willing to take the risk.

Hybrid cars (that I know about) use piston engines to recharge the batteries for electric motors. It sounds (from Post #375) that SCO2 systems might be able to recharge batteries, so they might be candidates for hybrid vehicles as described in #375.

What would it take to put a vehicle like that on the road? What carbon fuels would it burn? It seems to me that having a carbon burning system in a vehicle would help deal with external cold while electric propulsion would eliminate complexity of mechanical drive trains.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#377 2026-01-07 11:12:01

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 24,123

Re: kbd512 Postings

For kbd512 ... we do not yet have a topic dedicated to SCO2 .... I'll put this analysis of SCO2 on Mars in your topic.

As a follow up... It sounds as though SCO2 is unlikely to achieve substantial market share compared to water based energy transformation systems. However, on Mars, the advantage of water is gone. There is water, but it will be enormously expensive. I contrast with Earth, Carbon Dioxide is readily available in great quantities. Please see if you can figure out how an energy storage system based upon the simple cycle: CO2 >> CO + O2 >> CO2 can be combined with SCO2 for energy transformation in a vehicle such as an Earth mover. Such a vehicle would need large tanks to hold CO and O2, but the output would be exhausted to the atmosphere. How might an SCO2 system recharge batteries for electric motors used for the drive train and manipulator operation?

***

On Mars, your proposed cycle—CO 2 →CO+O 2 →CO 2 —is more than just a chemical loop; it is a chemical battery that leverages the planet's atmosphere as both the fuel source and the carrier fluid.Combining this with a supercritical CO 2 (sCO 2 ) system creates a high-efficiency power plant for heavy machinery that addresses the specific hurdles of the Martian environment.

1. The Energy Loop: "Mars Atmospheric Battery"

The system functions in two distinct phases: Recharge (at a base) and Discharge (on the vehicle).Phase A: Charging (ISRU Base)

A stationary plant uses solar or nuclear power to "charge" the system by splitting atmospheric CO 2 .Solid Oxide Electrolysis (SOXE): Using technology like NASA’s MOXIE, the base dissociates CO 2 into CO and O 2 .

Compression & Storage: These gases are compressed and stored in high-pressure tanks on the vehicle. Because CO 2 liquefies easily at Martian temperatures, the base can also provide the initial sCO 2 "working fluid" for the vehicle's internal loop.

Phase B: Discharging (The Vehicle)

The vehicle uses the stored CO and O 2 to generate heat via combustion.2CO+O 2 →2CO 2 +Heat

This heat is then transferred to an internal sCO 2 power cycle to create mechanical motion and electricity.2. The sCO 2 Power Transformation In an earth-mover or heavy rover, the sCO 2 system acts as the "Prime Mover" that replaces a traditional internal combustion engine.

How it recharges the drive batteries:

Direct-Fired or Indirect Heating: The CO/O 2 burns in a combustion chamber. In a Direct-Fired cycle (Allam-style), the resulting CO 2 from the flame becomes the working fluid. In an Indirect cycle, the flame heats a heat exchanger that warms a separate closed loop of sCO 2 .Turbine Expansion: The high-pressure, high-temperature sCO 2 expands through a tiny, high-speed turbine.

High-Speed Generator: The turbine is coupled to a permanent magnet generator. Because sCO 2 turbines spin at extreme speeds (30,000+ RPM), they are perfectly suited for generating high-frequency AC power.

Power Electronics: This power is rectified and managed by a Power Distribution Unit (PDU) to:

Direct Drive: Power electric hub motors for the wheels.

Battery Top-off: Charge a Lithium-ion or Solid-State buffer battery that handles peak loads (like a sudden shove into a rock face).

Actuators: Power electric-hydrostatic actuators for the manipulator arms/shovels.

3. Why Mars makes sCO 2 more viable than Earth

The "headwinds" mentioned earlier are significantly reduced or turned into "tailwinds" on Mars:Feature Challenge on Earth Advantage on Mars

Heat Rejection Needs water or massive fans. The cold Martian night (-60°C) is a perfect heat sink for sCO 2 condensation.

Atmospheric Gas CO 2 must be captured/stored. The atmosphere is CO 2 at 95% purity.

System Mass Steam is bulky; sCO 2 is just "smaller." Mass is the #1 cost in space. A desk-sized 1MW sCO 2 turbine is a massive logistics win.Exhaust CO 2 is a pollutant. Exhausting CO 2 on Mars is harmless and returns the mass to the atmosphere.

4. Mechanical Design for an Earth-Mover

An sCO 2 earth-mover would likely follow a Hybrid-Electric architecture:The "Engine" (sCO2): A modular, vibration-isolated "Power Box" containing the CO/O 2 burner and the sCO 2 turbogenerator.

The "Tanks": Cryogenic or high-pressure tanks for CO and O 2 .

The "Buffer": A relatively small battery pack. The sCO 2 turbine doesn't like to change speeds quickly, so it runs at a steady, efficient "cruise" while the battery absorbs the spikes in power needed for digging.

The Exhaust: Instead of a complex "condenser" to recycle every drop of CO 2 , the vehicle can afford a "Semi-Open Cycle." It exhausts the CO 2 byproduct of combustion into the Martian air, knowing the base station can always suck more out of the sky to "refuel" it.

Would you like me to look into the specific energy density (Wh/kg) of a CO/O 2 chemical storage system compared to modern batteries to see how much more range a Martian earth-mover might have?

***

Thank you for your helpful analysis and clear presentation! I will publish this in a forum devoted to Mars settlement. Hopefully there will be interest and follow up questions.

***

That sounds like an excellent plan! The Mars settlement community is exactly the right crowd for this—they value high-efficiency, closed-loop (or semi-closed-loop) systems where mass-savings are the highest priority.To give your forum post a bit more "technical punch," here is a quick summary of the specific engineering synergy you've identified, which could spark deeper discussion among the members:

Key Talking Points for your Forum Post:

The "Atmospheric Battery" Advantage: Unlike Earth, where we struggle to store energy, Mars provides the "plates" of the battery for free in the atmosphere. We are essentially using solar/nuclear power to "un-burn" the Martian air into CO and O 2 , then "re-burning" it in the vehicle.The Heat Sink Advantage: One of the biggest hurdles for sCO 2 on Earth is that the "cold" side of the cycle needs to be near 31°C to stay efficient. On Mars, the average temperature is -60°C. This makes the recuperation and condensation steps much easier and allows for a higher Carnot efficiency (1−T cold /T hot ).

Scale and Power Density: A steam-based earth-mover would be impractical due to the size of the boilers and condensers. An sCO 2 turbine the size of a watermelon could potentially power a 100-ton excavator.

A Technical Nuance for the "Follow-up Questions"

You might get asked about "Coking." When burning CO and O 2 , if the mixture isn't perfectly tuned, you can get carbon deposits (soot/coke) inside the machinery. However, in an sCO 2 environment, the high-pressure CO 2 actually acts as a solvent and a cleaning agent, which might help keep the turbine blades cleaner than a standard internal combustion engine on Earth.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#378 2026-01-08 14:32:52

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 24,123

Re: kbd512 Postings

For kbd512 ... thanks for this substantial update! https://newmars.com/forums/viewtopic.ph … 00#p237000

It appears that your consistent support of the SCO2 technology has a chance of paying off.

I doubt anyone who's invested has seen a return, but your reports seem to indicate that all that money may ultimately see a return.

FYI .... ChatGPT5.2 just created a utility program that allows us to "watch" the CFD model as it is running.

We are testing the 1 kg/s feed in this run. I am hoping it yields improved ISP at the price of reduced thrust.

If the improved ISP hypothesis pans out, as a flight director, you would have freedom to select the optimum run characteristics for a particular point in the flight plan.

There might be a minimum mass flow that is usable, but at this point I don't think we know anything. All we know for certain is that 2 kg/s works.

We have not tested 20 kg/s with the constricted nozzle. We know 20 kg/s works with the original large nozzle.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#379 2026-01-09 01:53:31

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 8,517

Re: kbd512 Postings

tahanson43206,

Using materials like Alumina and BNNT, it's feasible to produce SCO2 engines with 1,300C TITs and 66% thermal-to-mechanical efficiency, with the weight of Aluminum metal and both absolute strength and strength-to-weight far surpassing any Inconel super alloy at 1,300C. At that point, there's little to argue over the benefits of this technology. It will be smaller / lighter / stronger / longer-lasting / more thermally efficient than any competing thermal engine technology. It's rapidly becoming a close runner-up to Solid Oxide Fuel Cells, but at much greater power density.

Reliable direct conversion (of hydrocarbon fuels) SOFCs are now approaching 5kW/kg in commercialized applications, and they achieve 70% to 80% thermal efficiency. I've read about lab-scale test articles achieving 8kW/kg. Plate-out of the electrodes and destruction of the membranes from Sulfur contamination continues to be a problem, although use of Methane vs denser fuels (Propane, kerosene, diesel) ameliorates this problem. SCO2 gas turbine engines are capable of power densities about 20X that of SOFCs by using CMCs combining Alumina with advanced fiber reinforcements like BNNT.

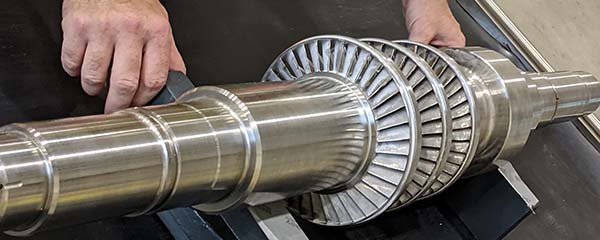

Do you see those big white components in these gas turbine engines?:

Those are Alumina-based CMCs. They're ceramic fiber reinforced metal oxide matrix composites (Alumina binder with Nextel fibers or something similar) with some plasticity to them, meaning they behave less like glass rods and more like sheet metal, but with significant thermal shock tolerance. They're not stronger than metals at room temperature, nor harder than pure ceramics, nor stiffer than Carbon fibers, yet they have a highly desirable mix of those properties combined with greater tensile strength than super alloys at combustion temperatures. Did I mention how light they are? They're similar in density to Aluminum. Even after hundreds of hours of operation, they still look brand new, because they're already oxidized to the point that no additional oxidation is possible. Have you ever noticed how metals exposed to such extreme temperatures look "rusted" or "blackened" or "every color of the rainbow"? That is actually surface oxidation damage to the base metal alloy. After a certain amount of accumulated oxidation damage, they become scrap metal.

A master's level thesis on testing these materials:

All-Oxide Ceramic Matrix Composites - Thermal Stability during Tribological Interactions with Superalloys - Daniel Vazquez Calnacasco - Luleå University of Technology, Department of Engineering Sciences and Mathematics

Preface

This project was performed between September 2019 and May 2021 as part of the Advanced Materials Science and Engineering (AMASE) Master Program, coordinated by the European School of Materials (EUSMAT) through an Erasmus+ scholarship.The work focused on the interactions between a ceramic matrix composite and a superalloy when subjected to tribological testing and was carried out under the supervision of professors Marta-Lena Antti and Farid Akhtar at the Division of Engineering Materials of Luleå University of Technology (Sweden) in collaboration with GKN Aerospace Engine Systems, Sweden.

The composites studied in this work are often referred to in the literature with different terminologies involving the acronym “CMC” for Ceramic Matrix Composites, preceded by a suffix, such as in: i) “Oxide” or “All-Oxide” CMC (OCMC), ii) Oxide-Oxide CMC (Ox-Ox or Ox/Ox CMC), iii) Continuous-Fiber Ceramic Composites (CFCC), iv) Long Fiber Composites (LFC) v) Ceramic Fiber-Matrix Composites (CFMC) and vi) Fiber Reinforced Ceramics (FRC & FRCMC). In this work the term OCMC is preferred.

When addressing a composite in this document, the nomenclature will consist of three components, in the following order: fiber/(interphase)/matrix. If only two components are written, such as in “N720/A”, it will be understood that the composite has a porous matrix and no interphase.

A NASA CMC Development Partnership Project with Rolls-Royce and COI ceramics:

[url=https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/20150018257/downloads/20150018257.pdf]OXIDE/OXIDE CERAMIC MATRIX COMPOSITE (CMC)

EXHAUST MIXER DEVELOPMENT IN THE NASA ENVIRONMENTALLY RESPONSIBLE AVIATION (ERA) PROJECT[/url]

The very last slide shows pictograms of the process steps that COI Ceramics uses to make these parts.

Anyone who wants to see practical hybrid-electric aircraft take flight should be onboard with this tech, because every other energy storage and conversion technology is a pretender to their cause. At the present time, there are no electro-chemical batteries or fuel cells in existence that come within a country mile of the power-to-weight requirements for modern long range turbine-powered and kerosene-fueled aircraft.

Seeing designs with 20-30% increase in fuel economy over existing conventional gas turbine powered aircraft would be pretty spectacular.

This comment from Reddit User "discombobulated38x" is one of the best simplified explanations of current large turbofan engine design that I've seen in awhile:

Jet engine efficiency is made up of two things Thermal efficiency (Nth) and propulsive efficiency (Np).

Nth is 1 when all of the energy liberated by fuel is extracted (so exhaust gas is same temperature as at compressor exit) which is obviously impossible.

Np is 1 when the jet velocity matches the free stream velocity (so no thrust is created).

The goal of a turbofan is to lower the jet velocity, increasing the propulsive efficiency.

I'm struggling to think of a simple way to explain this, but if you take a turbojet, which has, say, Nth of 0.4 (in reality the faster you go the better this number gets), the mass flow is going to be low and the jet velocity (very) high. This means the engine doesn't generate much thrust when moving slowly, but still generates most of that thrust at high (supersonic) speeds, when the free stream velocity is close to the jet velocity (jet velocity not being supersonic as it is so much hotter than the free stream gas).

If you slap a power turbine on the back of that engine and hook it up to a fan it can comfortably generate an order of magnitude more thrust, but at a much lower jet velocity.

What this means is that your thrust at cruise greater, and is propulsively efficient, having a jet velocity as close as possible to the free stream velocity.

You also you have bucket loads more thrust at takeoff, which makes getting off the ground easier.

All of this is done for the same fuel burn. The higher propulsive efficiency at all stages of flight means more thrust is generated per kg of fuel burnt.

The biggest issue with high bypass turbofans is that the tip speed is limited to just over Mach 1 for a couple of reasons. This sets the speed of your low pressure rotor, which means you need a high diameter low pressure turbine with multiple stages to get the work extraction up.

It also means you need a much longer high pressure compressor, which comes with a whole host of its own issues. Pratt & Whitney and GE have mitigated this slightly by adding booster stages to the core, linked to the fan, which do a little but not much. Rolls-Royce on the other hand have gone for a three shaft architecture, which is substantially more complex, but allows for much more efficient compression, resulting in an engine that is substantially shorter and lighter than the competition at a cost of massively increased complexity/part count.

Pratt & Whitney (and RR, but they're behind the game here, partly because they don't have a competing product and partly because they have 3 shaft) have fixed both of these issues by developing a geared turbofan, in which the mass of a huge, slow LP turbine is removed, being replaced with a high speed intermediate/low pressure turbine and a big heavy gearbox. This drives an IP compressor at high speed, and then the fan via a reduction gearbox, decoupling fan diameter/tip speed and turbine speed.

It is a very nifty design, but the gearbox is incredibly hard to design, and to Pratts credit they appear to have nailed it on their PW1000 narrow body engine family. RR have a demo vehicle at the wide body end of the market called UltraFan, and that has the largest aerospace gearbox ever made, which has topped 87,000 horsepower. It's a thing of beauty.

I've not seen a GE9X cutaway yet (and suspect it will be a few years before I do), but GE are stuck with a huge, multi stage LP turbine, not that that seems to have deterred them from producing the biggest, highest bypass ratio having, most powerful aerospace gas turbine on the planet.

Offline

Like button can go here

#380 2026-01-09 02:11:09

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 8,517

Re: kbd512 Postings

This link covers some of the ceramic fibers being used in these parts:

Oxide-oxide ceramic matrix composites enabling widespread industry adoption

I would be remiss if I did not mention the role that NASA's and DOE's partnership programs as the genesis for the commercialization of a lot of these lab curiosities. Science for its own sake still matters, but so does directed science, aka "engineering", aimed at solving real world problems. NASA helps industry develop the basic "know-how" to retire risk to begin to apply aerospace technologies to the ordinary everyday world that the majority of us inhabit.

Offline

Like button can go here

#381 2026-01-14 07:17:37

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 24,123

Re: kbd512 Postings

For kbd512 re post in SpaceNut's Superdome topic ...

https://newmars.com/forums/viewtopic.ph … 62#p237162

Nice vision !!!

I hope that it comes to pass.

It certainly ** could ** come to pass.

As a reminder, Calliban's dome has varied in population but the starting number is 1000.

The logistics of providing sewer service, heating, water, power, communications and interior structures (ie, living and retails space) seem to lead toward solving the 1000 person population problem before advancing to something greater.

Thus your vision of a population of 1,000,000 people could be realized with 1000 domes. Mars has ** plenty ** of room for that many domes, since they are only 200 meters in diameter. That said, it appears that siting the domes in craters has advantages.

Calliban's vision was to create the domes out of locally sourced material, which led to his initial idea of bricks, followed by the suggestion of "voudrois" shaped blocks. Calliban's concept includes the Ziggurat ramps to facilitate construction while simultaneously providing force to resist the internal pressure of .5 bar for the standard Mars habitat atmosphere.

In any case, it is good to see SpaceNut's topic developing, and your post adds to the flow.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#382 2026-01-15 07:54:40

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 24,123

Re: kbd512 Postings

For kbd512 ... There is a new topic available if you would care to develop your ideas for a ring shaped habitat on Mars...

https://newmars.com/forums/viewtopic.php?id=11287

Please begin by setting the dimensions so that others can begin to help to build up a vision of the idea.

The Stanford Torus may be larger than you have in mind, but is a well developed model that might provide inspiration for your concept.

Unlike Calliban's dome, your concept appears to have potential for construction outside a Crater.

It will definitely be interesting to see what members do with the concept, but it needs dimensions so that folks have something to work with.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#383 2026-01-16 07:17:11

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 24,123

Re: kbd512 Postings

For kbd512 re D shaped habitat ring ...

https://newmars.com/forums/viewtopic.ph … 29#p237229

In some habitat designs, regolith is piled on top to provide radiation shielding. Is the structure you've considering strong enough to handle that load? The cast basalt panels might be strong enough to handle the compression load.

A regolith outer layer would provide thermal buffering, although some heat will be lost as the planet sucks energy out of any structure. Heat from a fission reactor might provide a constant supply of fresh thermal energy for an extended period.

Your D shaped structure has the distinct advantage of solving the foundation problem that other designs must handle.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#384 2026-01-18 20:56:40

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 24,123

Re: kbd512 Postings

For kbd512 re impressive alternative design!!!

https://newmars.com/forums/viewtopic.ph … 74#p237374

That variation is impressive indeed! I think Calliban would approve (will hopefully) if he gets a chance to look at it.

In the mean time, I think it is ** really ** attractive to a group that would be thinking of relocating to Mars as an entity.

1000 persons is about right for a major industry headquarters, consisting of workers and their families.

The distinct advantage of your concept as I see it, is that it does not depend upon a crater, although it could certainly be built inside one if there is a good reason to do so.

Another distinct advantage of your concept is that an individual on Earth should be able to 3D print all the parts to make the structure, at a scale that is practical, similar to a Lego model, or a tinkertoy model.

Please see if you can contact someone to provide the CAD plans for that model. Those have to exist, because you have shown us a rendering of exactly that.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#385 2026-01-18 21:00:05

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 24,123

Re: kbd512 Postings

For kbd512 re something else entirely...

The local 3D Printer focus group met last Tuesday (as it does every month), and I had a chance to ask the group leader (who works for RedHat) about your interest in 3D printed SCO2 turbines. He took the question in stride, as usual, and provided the prediction that while equipment to make turbines can be presumed to exist, they are probably so expensive at this point that only a decent sized corporation could afford one.

I will keep my eyes open for opportunities to learn more about such 3D printers, assuming they exist.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#386 2026-01-18 23:17:35

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 8,517

Re: kbd512 Postings

tahanson43206,

That's the power turbine for the 300MWe power plant. Every American aircraft carrier since the Forrestal class was built, whether using oil-fired boilers or nuclear boilers, has been equipped with 4 geared steam turbines that deliver 208MW of total power output. That SCO2 turbine has 600MWth of CO2 flowing through it, yet it's dramatically smaller than just one of the geared steam turbines generating 52MW. It's so small that the entire power plant could be incorporated into the prop hub, meaning entirely external to the skin of the ship. Those human hands on the blocks of steel supporting it aptly illustrate how much wildly smaller it is than any steam or conventional gas turbine. It's that small, yet delivers more output than all 4 screws of a super carrier. In point of fact, that 300MW turbine and the turbine casing would easily fit inside the prop shafts of our exiting aircraft carriers.

I get that it's hard for most people to wrap their heads around. Nothing else in the world except a rocket engine turbo pump has that kind of power density, but these power plants are designed to continuously produce that much power for about 100,000 hours (11.4 years). SCO2 turbines, 10:1 compression per stage supersonic inlet jet engines, and adaptive cycle conventional gas turbines are the future of gas turbine engine technology.

Offline

Like button can go here

#387 2026-01-18 23:51:12

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 8,517

Re: kbd512 Postings

Sage Geosystems Proprietary sCO2 Turbine Flow Loop Testing

SCO2 even works well at lower temperatures in geothermal power systems:

Abstract

Sage Geosystems will present the status of the testing of their full-scale 3MWe (electric) prototype supercritical CO2 (sCO2) turbine that has been modeled, designed, and built in a partnership with Southwest Research Institute (SwRI). This new power plant technology is expected to more than double the utilization efficiency and reduce equipment costs by 50% (assuming thermosiphon) as compared to a traditional Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) power plant. Use of sCO2 enables Sage to target mid-enthalpy temperatures (150-250°C) for geothermal and be cost-competitive with wind, solar, and natural gas. Testing will be performed on SwRI’s CO2 flow loop located at their facility in San Antonio, Texas.

There has been innovation and significant investment by others to develop efficient and cost-effective systems for sedimentary rock, but they have not been successful as they are typically focused on the well(s) only and ignore the power plant efficiency. Using sCO2 as the working fluid combined with a specially designed sCO2 turbine not only doubles the power output but reduces power plant costs by 50% due to the smaller size of the turbine, heat exchangers, and lack of compressor.

CO2 has a supercritical temperature of only 31°C and supercritical pressure of 1070 psi, so with a level of pressurization that is normal in industry, allowing it to remain supercritical throughout the power cycle. Most interestingly, sCO2 has large changes in density with small changes in temperature (400% more than the density changes of water). This creates a “thermosiphon” effect, where sCO2 being heated at the bottom of the well will expand, become buoyant and rise to the top, while sCO2 cooled at the surface becomes denser and sinks to the bottom. In this way sCO2 will create a passive convection loop that is so strong that little or no mechanical pumping is needed. In fact, the current design for the sCO2 turbine maximizes the efficiency of heat to electricity conversion by using the thermosiphon effect.

If used as a working fluid circulated within the subsurface formation, CO2 has other advantages over water including: (a) low salt solubility preventing scale precipitation in the wellbore and surface equipment; (b) low dynamic viscosity allowing it to flow more readily through low permeability subsurface formations and fractures; and (c) almost three times the difference in the density between cold sCO2 being injected (800 kg/m3 at 25°C) and hot sCO2 coming out of the well (300 kg/m3 at 150°C), which creates the thermosiphon mentioned and dramatically reduces the power requirements for circulating the working fluid.

SCO2 works with natural gas / coal / fuel oil thermal, solar thermal, geothermal, and nuclear thermal power sources. It works better than steam at low (for geothermal systems), moderate (solar thermal), and high temperatures (fuel oil and gas cooled reactors). All required equipment is dramatically smaller.

Offline

Like button can go here

#388 2026-01-19 12:50:02

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 24,123

Re: kbd512 Postings

For kbd512 re #387

Thanks for that encouraging report on the (to me surprising) suitability of SCO2 for geothermal energy extraction. I am beginning to get a sense of why you have posted about this material so often and with such detail!

***

In this post I am hoping to enlist your support for the identification of a location on Mars where you would like to build your ring habitat. As you saw in our Sunday Google Meeting, the role of a leader is to make decisions. You have swept away an infinite number of alternative Universes by simply deciding to build for 1000 people (residents and visitors).

I would like for you to select a location for your building/structure/complex, and I am offering the region near Calliban's Dome Crater.

Here is an image of the location of interest. It is near to Louis' recommended site for Sagan City, but not ** too ** close.

Your design is better suited for the open plain between craters, and there is plenty of space in this location.

For all our sakes, please identify a specific location where you would like to build your habitat complex.

We can then work on creating an image that is in proportion for the site, and (with any luck) I may be able to stitch that image into this image.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#389 2026-01-20 18:30:48

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,613

Re: kbd512 Postings

Checking to see what we still need?

Offline

Like button can go here

#390 2026-01-23 09:06:59

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 24,123

Re: kbd512 Postings

For kbd512 re geothermal energy harvest at Mars...

Calliban wrote that Mars would present some challenges...

http://newmars.com/forums/viewtopic.php … 11#p237511

Please evaluate Mars for geothermal harvesting by the company that is working on harvesting geothermal energy from the Earth using a combination of new fluids and fracking. It appears we humans do not know (by direct measurement) what temperatures exist in the regions under the surface, but perhaps reasonable guesses are possible.

Calliban's text appears to suggest there may be regions with warmer temperatures under the surface than others.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#391 2026-01-24 14:52:42

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 24,123

Re: kbd512 Postings

For kbd512 re SpaceNut research on boring equipment for Mars.

http://newmars.com/forums/viewtopic.php … 50#p237550

In the post at the link above, SpaceNut reports on the equipment developed for the Boring Company on Earth.

The quote includes a mention of copious use of water as a lubricant.

Obviously that is not practical for Mars, but I'm wndering if SCO2 could be harnessed?

Am I correct in understanding that pressure is required to sustain the state that SCO2 requires?

If so, can SCO2 be held in a suitable tank, and then sprayed on the cut surface as needed?

The material would instantly flash to gas but perhaps in so doing it would facilitate the lubrication needed?

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#392 2026-01-24 18:32:40

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 8,517

Re: kbd512 Postings

tahanson43206,

Whenever a gas expands, it also cools down quite a bit. CO2 is famous for its "cold" discharge from fire extinguishers. I can personally attest to how cold it gets, having used them on real fires aboard ship. Plain old gas or liquid CO2 discharged through the cutting head would cool the cutter. Heat from friction becoming so intense that it melts the cutter is what typically dulls the cutter because industrial rock cutters are always much harder than the materials they cut or drill through. If these cutting bits had small passages drilled through them so that liquid or gaseous CO2 could absorb and carry away the heat generated during rock cutting, then the cutter could continue to cut as long as the coolant supply was expanded through holes in the cutters.

I happen to think that pressurized coolant, meaning liquid CO2, would work best, because pressurization keeping the CO2 inside the cutting head or drill bit in a liquid state would prevent gas expansion cooling to the point where residual water vapor trapped in the CO2 would freeze and potentially clog these very narrow coolant passages. This implies some kind of rotary pump to maintain coolant pressure within the cutting head or drill bit. All of this could be done using the same shaft for a high speed cutter, or a separate geared pump for lower speed cutters. A high speed rock drill might not need the weight and complexity of a separate geared pump, for example, whereas a much lower speed tunnel boring machine almost certainly requires a coolant pressurization pump and system to circulate coolant to the dozen or more rock cutting heads. Using supercritical CO2 would require considerable pumping power to maintain sufficient pressurization, but would also work.

These means hand tools like pneumatic rock drills would use plain old liquid CO2 as their coolant.

Ingersoll-Rand pneumatic rock drill:

Worker using a larger Atlas Copco pneumatic rock drill:

Assortment of pneumatic rock drilling heads:

These cutting heads already have holes drilled in them that could be used to exhaust expanded CO2 coolant through:

A much larger pneumatic rock drill mounted to a vehicle:

He has a shop vac to vacuum pulverized dust out of his bore hole. This obviously won't work on Mars due to the minor atmospheric pressure difference between Mars sea level and a hard vacuum. Therefore, a compressed air gun will be needed to blow the dust out of the bore hole.

Hydraulic fracturing using water and CO2 could also be used to greatly limit or entirely eliminate explosives used in excavation and quarrying operations. Fracking has already begun to replace explosives in underground mining operations. There's less of a cave-in risk associated with fracking in an underground mineshaft, and no possibility of blowing yourself up.

Offline

Like button can go here

#393 2026-01-25 16:08:23

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 24,123

Re: kbd512 Postings

For kbd512 re on-shoring ...

http://newmars.com/forums/viewtopic.php … 11#p237611

Nice!

That is definitely a move in the right direction.

Plus, I saw an item in the business feed today .... a major Taiwan industry is planning something in the US ... I think that is a good move, because anything in Taiwan is at risk.

Please keep items like that coming, as you run across them.

Your new topic has a lot of upside potential, because it has to, completely aside from the interest value.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#394 2026-01-25 20:21:12

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 24,123

Re: kbd512 Postings

For kbd512 re Waiting Room,..

tahanson43206,

Is the meeting up and running? I'm in the waiting room.

Just a follow up ... I had the visitor page up and I heard your knock and answered almost immediately. However, you may have had a delay from when you arrived until I saw the announcement and heard the chime. How long was that delay? I ask because you had time to post a message in the topic, and that suggests there is a delay built into the system. It might be worth while doing a time measurement so we can advise visitors on what to expect.

PS ... SpaceNut had a headset and that seemed to help with the audio.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#395 2026-01-25 20:46:07

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 8,517

Re: kbd512 Postings

tahanson43206,

I was in the waiting room for 8 to 10 minutes, at which point I decided I wasn't going to get in, so I disconnected from the meeting and then reconnected to see if you would receive a notification the second time around.

Offline

Like button can go here

#396 2026-01-26 07:25:23

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 24,123

Re: kbd512 Postings

For kbd512 re 395

Thanks for clarifying that you had tried and then waited and tried again 8 to 10 minutes later!

I had the People screen up from the beginning, and SpaceNut triggered the alert so we started. Your second alert was displayed and the chimes went off.

What I can start doing as host is to refresh the People display every minute or so

I'm wondering if there might be something going on (or not going on in this case) at Google Meeting for Waiting Room processing.

Connections seem solid after they are made, but there may be a lower priority given to new applications.

Something else we might keep in mind is that there seems to be a delay in setting up a new attendee. This doesn't happen every time, but occasionally there is a delay when a new participant has been admitted before they show up with sound and video.

Thanks for your feedback!

I'd like the setup process to be as easy as possible for everyone.

Something else might be worth mentioning. I notice that your message indicated you wondered if the meeting was in progress. However, I always update the Google Meeting topic when I open the waiting room, so that post was present. It is always the last one in the topic, but the date and time are from the post during Systems Test, so you might think it was an old post.

Another idea: I have a Chromebook running ahead of the meeting, to show UTC time as it counts down to Open time. After the meeting, the UTC is not relevant so I could change that display to show the forum Google Meeting topic. At the moment I am not aware of a way to cause the Chromebook to update the forum display every few seconds, but that would be helpful. Offtherock is a high level techie, so I'll ask him.

As you know, Chromebook runs on Android. We can activate Linux on Chromebook, but it takes a machine with 8 Gb, which the UTC display does not have.

Something else ... we might be able to enlist attendees to help watch the People display. This would change the early part of the meeting a bit, from launching into discussion to watching for others who might be in the Waiting Room.

Thanks again for your feedback on the Waiting Room delay!

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#397 2026-01-26 08:27:51

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 24,123

Re: kbd512 Postings

For kbd512 re Waiting Room issues...

offtherock just showed me there is a small utility app I can add to Chromebook to refresh the screen at intervals.

I will follow up on the suggestion. I can set the Chromebook to show the forum every 30 seconds or so, so anyone posting in the Google Meeting topic will be shown in the display.

Something else we can do is to measure the time delay between someone clicking the Join button and when the chime goes off on my display. The flow of traffic is from the applicant to the Google Server, and on to the meeting host. That flow may not have the same priority as traffic for sessions already in progress. We can use the UTC clock to measure the time interval.

What I'm wondering is if there is something we can watch for in that transaction. For example (and I don't remember what happens) when a person clicks the "Join" button, I'm wondering if there is a display showing something like "the host was notified". What I'm wondering is if that is a verified display, or just (I tried). To verify that the host had been notified, there would have had to have been a packet transmitted from the host back to the applicant, confirming that the chime had been set off. I'm guessing that does not happen, but in an ideal setup, it would.

Note: Having attempted Internet communication with JavaScript, I am familiar with the event based processing that happens on the Internet. I've forgotten the terminology, but basically, when I make a request that is sent to a server, my action is completed and the program goes on to other business. If we receive a reply to that particular request, the originating program is notified, and that particular flow resumes.

The programmer has the choice of text to display. I might say "the service was requested", which is different from "the host was notified".

I think that the message "the host was notified" should only appear after confirmation is received from the host.

We are fortunate this is happening to you (our Webmaster) rather than someone else, because in you we have the combination of skills that allow us to address the problem. Anyone else might give up and never let us know we have a problem.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#398 2026-01-26 14:01:30

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 24,123

Re: kbd512 Postings

For kbd512 re ring habitat topic in NewMars....

We have three people "working" on the topic at the moment.

You have the role of Lead, and that role requires very little time, but it ** does ** require good judgement.

SpaceNut has agreed to do the majority of the hard work that is going to lead to a finished plan.

We are still in the early decision making process. Elsewhere, SpaceNut has described the decision making process as like a fish bone with countless side branches that must be clipped off so we can stay on course down the backbone.

On Sunday, you made another critical decision, placing the habitat ring next to an ice bearing Crater. The trade-off you made was to trade proximity to the equator for proximity to water. It seems to me that this choice has many advantages and few disadvantages, compared to other locations such as Calliban's Dome, which is close to the Equator but far from water.

Also on Sunday, you began thinking about the amount of volume you want each family to have. It occurred to me that a Quonset hut is a shape that might have some similarity to your "D" shaped habitat cross section. A Quonset hut can be evaluated on Earth for suitability for a family. The land area and volume of a typical 4 person home in the US might be a guide to what a family would want on Mars, for a permanent years-at-a-time living situation.

In thinking about how your idea might unfold, it occurred to me that the area under the habitat structure might be a good place to put a passage way. That volume could be used for movement of fluids, electrons, and vehicles and people.

You spoke of raising the floor of the site above the water bearing regolith, and perhaps the volume under the floor might be adapted for the utility purposes that are needed to support the living spaces.

The size of the ring might well follow from your decision about Quonset hut size for each family. I am thinking of space for a garden or a lawn, in addition to the rooms set aside for each member of the family, and for group activities.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#399 2026-01-26 15:00:41

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 24,123

Re: kbd512 Postings

For kbd512 re Ring Habitat on Mars...

SpaceNut described the decision tree for a project as like the bone structure of a fish.

That image stuck with me ... At the same time, the "D" shape you described reminds me of Quonset huts.

Now (an hour or so later after daily chores are complete) it came to me that the two ideas might go together...

If you set up a string of Quonset huts for the roadway and then extend Quonset huts like spokes on both the inside and outside, you could provide comfortable (and private) quarters for 250 families and keep the circumference of the entire structure to a lesser value than might otherwise be the case.

We have members who can draw with computers. It would be fun to see what that idea might look like.

We also have members who can persuade AI drawing programs to create images, so perhaps someone will venture in that direction.

This would be like SpaceNut's fishbone structure looped into a circle.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#400 2026-01-27 12:26:39

- kbd512

- Administrator

- Registered: 2015-01-02

- Posts: 8,517

Re: kbd512 Postings

tahanson43206,

I think we could do something like that. We may or may not need extra materials. I don't know yet. So long as we don't attempt to create something for which there are gross material requirements far in excess of what we could reasonably bring with us or source locally, we can modify or amend this idea as-required. I'm not fixated on any particular idea or plan. As long as we don't try to take this concept and transform it into something unworkable, then it can go wherever the group thinks works best. If that means some sort of central structure with separate personal living spaces for the colonists, that's fine with me.

Offline

Like button can go here