New Mars Forums

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

Announcement

#26 Re: Exploration to Settlement Creation » WIKI Project Designing for Mars » 2026-01-11 16:28:55

Mars in-situ regolith mining equipment involves robotic excavators (like RASSOR/Razer), drilling/microwave probes for volatiles, and processing units for extracting water, metals (iron/steel), and oxygen, using systems like Solid Oxide Electrolysis Cells (SOEC) (MOXIE heritage) and 3D printing for construction materials, with key technologies focusing on automation, heat recycling, and handling abrasive Martian dust for ISRU (In-Situ Resource Utilization).

Key Equipment & Technologies

Excavation & Collection:

Robotic Excavators/Rovers: Systems like RASSOR 2.0 and Razer use counter-rotating drums or buckets for digging in low gravity, designed for high volume and autonomous operation.

Microwave Probes: Non-excavation method to heat subsurface ice, turning it into vapor for collection, reducing mass/cost of heavy machinery.

Processing & Extraction (ISRU):

Water/Volatiles: Extraction from regolith via microwave sublimation or drilling, followed by purification (membranes, distillation) and electrolysis to produce hydrogen (fuel) and oxygen (life support).

Metals & Oxygen: Systems (like MMOST) use electrolysis and reduction processes (e.g., using H₂/CO) to extract iron, steel, and oxygen from iron oxides in regolith.

Sifting/Refining: Machinery to achieve optimal particle size for construction aggregates, often involving heating and mixing with binders like sulfur.

Manufacturing & Construction:

3D Printers: Use processed regolith (sintered, mixed with binders) to build structures, reducing reliance on Earth-imported materials.

Sulfur Concrete Units: Heated mixers (pugmills) to combine regolith aggregate with molten sulfur (around 120°C) for bricks.

Key Processing Units:

Solid Oxide Electrolysis Cells (SOEC): Efficiently split water and CO₂ into constituent gases (H₂, O₂, CO) for chemical processing.

Heated Mixers/Kilns: For creating construction materials like sulfur concrete or sintering regolith.

Challenges & Considerations

Automation: Mining must be fully robotic and autonomous due to distance and communication delays.

Abrasion: Martian dust is highly abrasive, requiring robust seals and durable components.

Power & Logistics: Requires reliable, renewable power and efficient transport/storage systems.

High-Fidelity Simulants: Accurate testing relies on materials like MGS-1C (clay-rich) and MGS-1S (sulfate-rich) to mimic real Martian conditions.

Example System (Conceptual)

An integrated system might include a Razer excavator, feeding a processing unit that uses SOECs and heat recycling to produce oxygen, water, and metal powders, with a 3D printer using these materials to build habitats.

To build with Mars regolith, milling equipment (like vibratory/planetary ball mills) reduces particle size, while separation methods use techniques like laser sintering, cold sintering (CSP), polymer binders, or microwave systems to bind or melt regolith into structures, often requiring 3D printers for shaping, aiming for materials like bricks, shielding, or metal parts from extracted elements like iron/titanium. Key processes involve size reduction (milling) and consolidation (sintering/binding) to create usable materials like "Mars concrete" or fused components, with focus on robotic, energy-efficient systems.

Milling Equipment & Processes

Ball Milling (Planetary/Vibratory): Used to reduce particle size (PSD) of raw regolith simulant, with planetary mills being faster but roller banks better for large slurries.

Sieving: Separates milled particles into specific size ranges (e.g., 60-mesh).

Separation & Consolidation Technologies

Laser Sintering: Uses high-power lasers to melt and fuse regolith into solid layers, creating paving or structural elements.

Cold Sintering (CSP): Binds regolith with water/alkaline solutions at low temperatures (under 250°C) and pressure, forming strong bricks or blocks.

Polymer Binders: Mixes regolith with polymers (made from Martian CO2/water) for 3D printing concrete-like materials.

Microwave/Solar Sintering: Alternative methods to use focused energy for hardening regolith.

Metal Extraction: Processes like carbonyl metallurgy or vapor deposition extract iron and other metals for 3D printing steel parts.

Additive Manufacturing & End Products

3D Printing (Extrusion/Powder Bed): Deposits processed regolith/binders layer-by-layer, building structures like domes, habitats, tools, or rebar.

Products: Sintered bricks, concrete-like blocks, radiation shielding, metal components (rebar, gears, tools), and coatings.

Key Considerations

In-Situ Resource Utilization (ISRU): The core principle, maximizing use of Martian soil.

Energy Efficiency: Focus on low-energy methods like cold sintering.

Robotics: Automation is crucial for mining, milling, and construction

Final product sizes and applications

0–5 mm: Manufactured sand for concrete, dry-mix mortar, asphalt mix

5–10 mm: High-grade road base, permeable concrete

10–20 mm: Municipal projects, ready-mix concrete plants

20–31.5 mm: Railway ballast, highway base, mass concrete

>31.5 mm: Returned for re-crushing to ensure proper gradation

#27 Re: Exploration to Settlement Creation » WIKI Project Designing for Mars » 2026-01-11 16:27:10

In-situ (Latin for "on-site" or "in its original place") in the context of Mars construction refers to the practice of using local Martian resources, rather than transporting all materials and equipment from Earth. This is officially called In-Situ Resource Utilization (ISRU).

The core concept is "living off the land" to drastically reduce the enormous cost and logistical challenge of sending supplies across vast distances from Earth.

The idea that you would have no equipment at all is generally not feasible; some minimal, specialized equipment and robotic systems would be sent from Earth to act as the initial "factories" and "builders". How ISRU Addresses the "No Equipment" Constraint (Relatively) The goal is to minimize the mass and volume of material that must be launched from Earth, not to eliminate equipment entirely. Specialized, compact, and often autonomous, equipment would be sent first to leverage local materials.

The strategy involves: Sending minimal, critical machinery: Instead of sending heavy raw materials like concrete or steel beams, lightweight robotic equipment, 3D printers, and processing hardware are sent.

Utilizing local materials: The robots would use abundant Martian resources, primarily the soil (regolith) and atmosphere, to produce usable products.

Automated construction: The construction process would likely be managed by autonomous or semi-autonomous robots before humans arrive, allowing for the creation of habitats and infrastructure in advance.

Examples of In-Situ Resources for Construction With specialized equipment,

Mars offers several resources: Regolith (Martian soil): This can be used as a primary building material. Processes like sintering (fusing with heat) or mixing with binding agents (like an epoxy or sulfur) can create bricks, ceramics, and concrete-like structures for radiation shielding and general construction..

Water ice: Found below the surface, water is a critical resource. Once extracted, it can be used for life support (drinking water, growing food), split into hydrogen and oxygen (for breathing air and rocket propellant), or used in industrial processes.Atmospheric \(\text{CO}_{2}\): The Martian atmosphere is mostly carbon dioxide. Equipment like the MOXIE experiment on the Perseverance rover can extract oxygen from the atmosphere for life support and as an oxidizer for rocket fuel.

Basalt: Basaltic rocks are abundant and can be processed into glass or glass fibers, which have good insulating properties and can be used for construction. Essentially, "in-situ construction" is the practice of building with what you have on Mars, which is crucial for long-term sustainability and survival when resupply from Earth is nearly impossible

Basalt is a very hard, abrasive rock, so its processing for 3D printing requires robust, industrial-grade crushing and grinding machinery to produce the necessary fine powder or granule sizes. Typical crushing sequences involve multiple stages of specialized equipment, rather than a single machine.

Equipment for Basalt Crushing

A multi-stage process is typically used to break down large basalt rock into fine powder or granules suitable for applications such as fiber production or as an aggregate in 3D printed concrete.

Primary Crushing: Jaw Crushers

Purpose: The first stage of size reduction for large, raw basalt pieces.

Description: Jaw crushers are built strong with a deep crushing chamber to handle large, tough lumps of rock effectively, reducing them to sizes manageable by the next stage (e.g., from a meter down to a few inches).

Secondary/Tertiary Crushing: Cone Crushers or Impact Crushers

Purpose: To further reduce the basalt to a more uniform, smaller aggregate size (e.g., down to 0-40mm).

Description:

Cone crushers are highly recommended for hard, abrasive materials like basalt due to their durability and efficiency in producing a uniform, cubic product with lower wear rates than impact crushers.

Impact crushers can also be used, especially for shaping the material into a cubical form, but they tend to experience higher wear when processing hard basalt.

Fine Grinding (Milling): Ball Mills or Vertical Roller Mills

Purpose: To achieve the fine, micron-level powder needed for specialized 3D printing material composites, fillers, or fiber production.

Description: These machines use balls or high pressure to pulverize the basalt into the extremely fine particles required for additive

manufacturing processes.

Screening and Classifying Equipment

Purpose: To sort the crushed material by size and ensure the final product meets the required specifications for 3D printing projects.

Description: Vibrating screens are used after each crushing stage to separate the desired product sizes from oversized material, which is then recirculated for further crushing. Air classifiers or washers may also be used to remove impurities and achieve specific material properties.

Considerations for 3D Printing Projects

Particle Size and Shape: 3D printing requires a consistent and specific particle size distribution (PSD). The equipment used must be able to produce material within narrow tolerances.

Material Abrasiveness: Basalt is highly abrasive, with a Mohs hardness of 5-9. Equipment must have heavy-duty construction and wear-resistant liners (e.g., tungsten carbide components) to withstand the wear and tear.

Scale: For hobbyist or small-scale projects, small-scale jaw crushers might be available, though they are primarily industrial machines. For industrial 3D printing applications (e.g., large-scale additive construction using basalt-based concrete), a full production line is required.

Companies like Rubble Master, Zoneding Machine, and FTM Machinery manufacture industrial basalt processing equipment, and platforms like Alibaba.com list a variety of crushers and mills

A comprehensive iron ore processing and steel production facility on Mars would require an integrated suite of mining, comminution, beneficiation, and refining equipment. A 200-meter diameter is a massive scale, likely referring to the entire facility's footprint rather than a single piece of equipment, and would enable significant production capacity.

Required Equipment: The equipment would function in a sequence from raw material extraction to finished product, much like on Earth, but adapted for the Martian environment and the use of in-situ resources.

1. Mining and Raw Material Handling Excavation and Loading: Robotic rovers and excavators with magnetic systems could collect iron-rich regolith or access concentrated ore deposits.

Transportation: Robust, self-driving transport systems (e.g., heavy-duty rovers or a rail system) to move ore from the mine to the processing plant.

Crushing and Grinding: Equipment such as jaw crushers, hammer mills, and ball mills would be needed to break down the iron ore into fine particles for processing.

2. Beneficiation and Concentration Sizing and Screening: Vibrating screens and classifiers to sort particles by size.

Separation: Magnetic separators are key for iron ore beneficiation, potentially complemented by flotation equipment, to increase the iron concentration in the ore.

Dewatering/Filtration: Equipment like filter presses or vacuum filters would be necessary if wet processing is used, to remove water from the concentrated ore.

3. Iron & Steel Production Martian steelmaking would likely favor direct reduction or electric arc furnaces over traditional blast furnaces due to the lack of abundant coking coal and the availability of atmospheric \(\text{CO}_{2}\) and water ice for reactants/power generation.

Ore Agglomeration: Pelletizing or sintering machines to form the fine concentrate into larger, usable pellets.

Reduction Reactors/Furnaces:Direct Reduction Kiln: Equipment to reduce iron oxides using hydrogen and/or carbon monoxide derived from Martian resources.

Electric Arc Furnace (EAF): An EAF would melt the sponge iron (produced from direct reduction) and allow for the controlled addition of carbon (extracted from the Martian atmosphere's \(\text{CO}_{2}\)) and other alloying elements to produce specific steel grades.

Continuous Caster/Molds: Machinery to form the molten steel into basic shapes (e.g., billets, slabs) for further processing.

Ladle Furnace: Used for final refining of the steel.

4. Manufacturing and Finishing Rolling/Finishing Mills: Large mills to shape the raw steel into plates, sheets, beams, or pipes.

Additive Manufacturing (3D Printing): Metal powder bed fusion or directed energy deposition machines could use the produced steel powder for on-site fabrication of parts and infrastructure. Infrastructure and Support Equipment Power Systems: The entire process requires enormous amounts of power, suggesting large-scale nuclear fission reactors or extensive concentrating solar power (CSP) fields and storage systems.

Gas Processing Plant: A complex system involving electrolysis cells (like NASA's MOXIE technology) and chemical reactors (e.g., Sabatier reaction) to produce the necessary oxygen, hydrogen, and carbon monoxide from the Martian atmosphere and water ice.Habitat and

Maintenance Facilities: Pressurized environments, repair shops, and storage facilities for personnel and spare parts.Fume Extraction Equipment: Systems to manage and clean process gases, essential for operational efficiency and safety in a closed environment

#28 Re: Exploration to Settlement Creation » WIKI Project Designing for Mars » 2026-01-11 16:27:03

combining stuff

#29 Re: Exploration to Settlement Creation » WIKI Project Designing for Mars » 2026-01-11 16:26:52

Mars settlement projects typically progress through phases from initial robotic exploration and small outposts (Pre-settlement) to permanent, growing settlements with developing infrastructure (In-settlement), culminating in self-sufficient, potentially terraformed societies (Post-settlement), focusing first on establishing basic life support, resource utilization (ISRU), energy, and habitats before expanding to a city-like presence with economic independence. Key stages involve robotic reconnaissance, crewed landings, building propellant plants, establishing habitats, developing local agriculture, mining, and transitioning to self-sufficiency, requiring advances in transportation, closed-loop life support, and energy systems.

Key Phases & Stages

1. Pre-Settlement (Robotic & Early Outpost):

• Robotic Reconnaissance: Detailed surveys, sample collection (e.g., Perseverance), testing technologies for fuel/oxygen production from the atmosphere.

• Cargo Pre-Deployment: Sending autonomous cargo, including fuel production equipment, before human arrival.

• First Crewed Missions: Establishing a rudimentary base, completing the propellant plant for return fuel, and testing life support.

2. In-Settlement (Permanent & Growing Colony):

• Infrastructure Development: Building habitats, mining water, growing crops, creating power systems (solar/nuclear).

• Resource Utilization (ISRU): Extracting and processing Martian resources (water, metals, minerals) for construction and fuel.

• Population Growth: Increasing crew sizes, developing a local economy, and establishing governance.

3. Post-Settlement (Self-Sufficiency & Beyond):

• Industrial Independence: Scaling up mining, manufacturing (3D printing, metals, plastics) to reduce Earth reliance.

• Societal Development: Growing into towns/cities, developing unique Martian culture, governance, and potentially independent political structures.

• Terraforming (Long-Term): Modifying the environment to create breathable air and habitable zones, a highly speculative long-term goal.

Key Technologies & Goals

• Transportation: Reliable, efficient Earth-Mars transport (e.g., SpaceX Starship).

• Life Support: Perfecting closed-loop systems for air, water, and food.

• Energy: Sustainable power generation (solar, nuclear).

• ISRU: Water extraction, atmospheric processing for fuel/oxygen, material processing.

• Habitats: Durable, radiation-shielded shelters (surface and underground)

Mars settlement projects, like SpaceX's vision, progress through phases: pre-settlement (outposts), in-settlement (permanent bases), and post-settlement (self-sufficient society), aiming for crewed landings in the late 2020s/early 2030s and self-sufficiency by mid-century, requiring massive initial cargo (Starships carrying 100+ tons) for habitats, life support, and resource utilization (ISRU) like water and fuel production from Martian air and ice, with the ultimate goal of a large, self-sustaining population.

Phases of Development (Conceptual)

1. Pre-Settlement (Exploration & Outpost)

• Focus: Robotic missions, establishing basic infrastructure, resource identification (water ice, minerals).

• Key Tech: Advanced rovers, ISRU (In-Situ Resource Utilization) for oxygen/methane (fuel/air).

• Timeline: Current robotic exploration, early cargo missions (late 2020s).

2. In-Settlement (Permanent Base)

• Focus: First human landings, establishing initial habitats, expanding resource production (ISRU, agriculture), reducing Earth dependency.

• Key Tech: Habitable modules, power systems, water processing, basic manufacturing.

• Timeline: First crewed landings (early 2030s), developing permanent presence.

3. Post-Settlement (Self-Sufficient Society)

• Focus: Large-scale population, full industrialization, economic self-sufficiency, cultural development.

• Key Tech: Advanced manufacturing, large-scale life support, robust local economy, potential for terraforming elements.

• Timeline: Decades-long process, aiming for self-sufficiency by 2050+.

Timeline & Mass Estimates (SpaceX Example)

• Early Missions (2020s-2030s): Cargo & Crew via Starship (100+ tons capacity).

• Cargo: Essential for habitats, initial supplies, ISRU equipment.

• Crew: Small groups (4-10+), increasing over time.

• Self-Sufficiency: Goal by 2050, requiring a million people using numerous Starships over many launch windows (every ~26 months).

Mass Requirements & Challenges

• High Mass: Water, air (oxygen/nitrogen), fuel, food, equipment, habitats.

• ISRU Critical: Extracting water ice and using atmospheric CO2 for oxygen and methane fuel (CH4) is essential to reduce launch mass from Earth.

• Example: Water is heavy; a Starship (100 tons payload) could carry enough water for 20 people for years, but continuous resupply is needed.

In essence, Mars settlement requires a phased approach, leveraging current tech like Starship for massive cargo delivery, transitioning from outposts to permanent bases, and finally, fostering self-sufficiency through local resource utilization to support a growing population

#30 Re: Exploration to Settlement Creation » WIKI Project Designing for Mars » 2026-01-11 16:25:09

Project design goals for Mars construction center on sustainability, autonomy, and protection, focusing on using local resources (regolith) via 3D printing, pre-fabrication, and robotics to build habitats resistant to radiation, dust, and extreme temperatures, ensuring life support while minimizing Earth-based supplies and maximizing habitat modularity and long-term functionality for crew safety and expansion.

Core Design Goals

1. In-Situ Resource Utilization (ISRU):

• Use Regolith: Harvest Martian soil (regolith) as the primary building material for 3D printing structures.

• Create Building Materials: Develop methods (like laser sintering) to turn regolith into strong, durable construction materials (e.g., ceramic-like structures).

2. Autonomy & Robotics:

• Autonomous Construction: Deploy robotic swarms to excavate sites, print structures, and prepare habitats before astronauts arrive.

• Versatile Robots: Use robots with interchangeable tools for various tasks, including printing, sensing, and repair.

3. Environmental Protection:

• Radiation Shielding: Design structures with thick regolith shells or underground placement to shield against cosmic radiation.

• Thermal Management: Build to withstand extreme temperature fluctuations.

• Dust Mitigation: Incorporate robust designs and materials to handle corrosive Martian dust.

4. Sustainability & Efficiency:

• Minimize Earth Cargo: Reduce reliance on Earth by building with local materials.

• Energy Efficiency: Optimize shapes and use materials to minimize energy needed for construction.

• Waste Repurposing: Recycle waste into new furniture or parts using 3D printing.

5. Habitability & Modularity:

• Modular Design: Create connectable habitat units for easy expansion and resource sharing.

• Zoned Interiors: Separate wet (lab, kitchen) and dry (bedroom, workstation) areas for efficient resource use.

• Pressurized Cores: Use inflatable or prefabricated modules for the core pressurized areas, covered by the 3D-printed regolith shell.

6. Long-Term Viability:

• Durability & Repairability: Design components for long operational lifetimes and ease of onsite repair.

• Scalability: Create systems that can grow from initial outposts to larger settlement

#31 Re: Exploration to Settlement Creation » WIKI Project Designing for Mars » 2026-01-11 16:24:48

The concept of using a Starship cargo lander as a long-term habitat on Mars, sometimes called a "caretaker" or base camp, is central to {Link: NASA and SpaceX's Mars colonization vision, involving converting the massive lander into a livable base after its initial cargo delivery, with conceptual studies exploring how to offload and configure these huge structures, potentially using other Starships or specialized equipment for setup.

Key Concepts & Plans

Starship as Lander & Habitat: Starship's enormous payload capacity (up to 150+ metric tons) allows it to deliver not just supplies but also become a primary habitat on Mars after landing.

NASA's Common Habitat Architecture: NASA studies, like the "Common Habitat," envision using SLS core tanks or Starship-derived modules as large, long-duration habitats, leveraging the work on Starship landers for delivery and setup on the Moon and Mars.

Phased Deployment: Early cargo Starships land, offload equipment, and then potentially serve as initial shelters, with later, larger modules or converted Starships forming the core of a permanent base.

Deployment & Setup: A major challenge is getting the habitat off the lander and onto the surface, with studies exploring cranes, jib systems, or even other Starships to maneuver and position these massive structures.

Caretaker Role: The lander itself, or a dedicated Starship habitat, would provide immediate shelter, life support, and a base of operations, acting as a "caretaker" until larger, purpose-built habitats are established.

How it Works (Conceptual)

Launch & Transit: A modified Starship carries cargo and/or habitat components to Mars.

Landing: The Starship performs a powered landing on Mars.

Habitat Activation: The vehicle is configured (potentially by another Starship or robotic systems) to become a habitable zone, with internal decks, life support, and living quarters.

Expansion: Subsequent Starship deliveries bring more components to build out a larger, more permanent base around the initial lander habitat.

This approach leverages Starship's unique capabilities to drastically reduce the complexity and cost of establishing a long-term human presence on Mars

Project design for exploratory missions involves defining clear objectives, assembling diverse expert teams, developing concepts of operation (ConOps), conducting trade studies (AoA), identifying risks, and iteratively planning detailed activities using specialized software, all within structured life cycles (like NASA's) to move from initial ideas to a flight-ready plan, focusing on flexibility and measurable success. Key steps include envisioning, building minimum viable products (MVPs) for testing, deploying, observing, and deciding whether to cancel or productize the concept, all while managing constraints and contingency needs.

Key Stages & Activities

Concept & Definition (Envisioning):

Define Purpose & Objectives: Establish clear, SMART (Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant, Time-bound) goals (e.g., scientific discovery, tech advancement).

Stakeholder Engagement: Involve science experts, engineers, project managers, and users to capture needs and goals.

Develop ConOps: Outline how the mission will operate, from launch to data collection.

Design & Analysis (Build & Observe):

Trade Studies (AoA): Evaluate alternatives for systems, trajectories, and operations.

Technology Development: Test hypotheses through building and deploying MVPs (Minimum Viable Products).

Risk Identification: Classify and identify initial technical risks.

Software Tools: Utilize tools like NASA's GMAT for trajectory design or SPICE for observation planning.

Planning & Iteration (Deploy & Productize):

Detailed Planning: Create specific activity plans, including contingency plans (e.g., backup Trajectory Correction Maneuvers - TCMs).

Flexibility: Use flexible plans that allow for adjustments (e.g., MAPGEN for Mars rovers).

Testing & Validation: Perform operational readiness tests (ORT).

Iterative Cycles: Loop back to refine plans based on observations and actual constraints.

Core Principles

Iterative & Adaptive: Plans evolve to meet changing constraints and priorities.

Data-Driven: Observation and measurement guide decisions.

Cross-Disciplinary: Success requires integrating science, engineering, and operations.

Risk Management: Proactive identification and mitigation of risks are crucial.

Example Frameworks

NASA's Lifecycle: Moves from concept to formulation, development, and operations.

Disciplined Agile (DA): Uses an exploratory lifecycle with envision, build, deploy, observe, and cancel/productize phases.

The primary project design goals for Mars construction management are centered on sustainability, self-sufficiency, safety, and efficient resource utilization due to the extreme and isolated environment. These goals ensure human survival, scientific advancement, and a foundation for a potential long-term settlement.

Key design goals include:

Survival and Safety

Radiation Protection: Designing structures, often buried or semi-buried, that provide robust shielding from the high radiation levels in the Martian environment.

Environmental Protection: Protecting crew, hardware, and electronics from extreme temperature variations, atmospheric differences, and micrometeorites.

Structural Integrity and Pressurization: Engineering buildings capable of withstanding the internal pressure of a breathable atmosphere within the thin Martian atmosphere, managing associated tensile stresses.

Reliable Life Support Systems: Integrating robust and redundant life support systems (oxygen generation, water recycling, waste management) to create a self-sustaining environment.

Resource and Efficiency

In-Situ Resource Utilization (ISRU): Minimizing the mass of materials transported from Earth by leveraging local Martian resources (regolith, basalt, water ice, etc.) for construction, which is a major cost and logistics driver.

Additive Construction (3D Printing): Utilizing autonomous or semi-autonomous 3D printing technologies to build infrastructure (landing pads, habitats, roads) with minimal human involvement and using local materials.

Energy Efficiency and Generation: Designing systems that require minimal energy consumption for material processing and operations, while integrating reliable surface power sources, such as nuclear power.

Functionality and Habitability

Scalability and Adaptability: Designing initial systems that can be incrementally expanded and modified to meet the needs of a growing population with minimal recurring development effort.

Maximizing Interior Space and Habitability: Creating functional layouts that maximize usable space and provide a psychologically comfortable living and working environment to support long-duration missions and a healthy work-life balance.

Support for Science and Operations: Ensuring infrastructure supports a wide range of activities, including scientific research, testing, and eventual industrialization, beyond just basic survival.

Autonomy: Developing construction hardware and processes that can operate autonomously or be managed with minimal oversight from Earth, given the communication delays and operational challenges.

These goals require collaboration across multiple disciplines, including civil and aerospace engineering, architecture, and material science, often utilizing advanced technologies and rigorous project management methodologies to control cost, schedule, and risk. NASA's Moon to Mars Planetary Autonomous Construction Technology (MMPACT) project is actively developing many of these capabilities on the Moon as a stepping stone for future Mars missions

Living and Working on Mars

Oxygen

The Mars Oxygen In-Situ Resource Utilization Experiment, or MOXIE, is helping NASA prepare for human exploration of Mars by demonstrating the technology to produce oxygen from the Martian atmosphere for burning fuel and breathing.

Food

Astronauts on a roundtrip mission to Mars will not have the resupply missions to deliver fresh food. NASA is researching food systems to ensure quality, variety, and nutritional values for these long missions. Plant growth on the International Space Station is helping to inform in-space crop management as well.

Water

NASA is developing life support systems that can regenerate or recycle consumables such as food, air, and water and is testing them on the International Space Station.

Power

Like we use electricity to charge our devices on Earth, astronauts will need a reliable power supply to explore Mars. The system will need to be lightweight and capable of running regardless of its location or the weather on the Red Planet. NASA is investigating options for power systems, including fission surface power.

Spacesuits

Spacesuits are like “personal spaceships” for astronauts, protecting them from harsh environments and providing all the air, water, biometric monitoring controls, and communications needed during excursions outside their spaceship or habitat.

Communications

Human missions to Mars may use lasers to stay in touch with Earth. A laser communications system at Mars could send large amounts of real-time information and data, including high-definition images and video feeds.

Shelter

An astronaut's primary shelter on Mars could be a fixed habitat on the surface or a mobile habitat on wheels. In either form, the habitat must provide the same amenities as a home on Earth — with the addition of a pressurized volume and robust water recycling system.

#32 Re: Exploration to Settlement Creation » WIKI Project Designing for Mars » 2026-01-11 16:24:16

Designing a Mars mission involves defining clear goals (e.g., find life, establish presence), setting specific objectives (e.g., collect samples, test life support), choosing mission types (robotic, human, precursor cargo), and detailed planning for technology, logistics (launch, propulsion, landing), science operations, and risk management, all within budget and schedule constraints, following a phased approach like NASA's Moon to Mars strategy.

Types of Mars Missions

Robotic Landers/Rovers: Focus on remote science (habitability, past life, geology), sample collection (Perseverance), and preparing sites for humans (e.g., Mars 2020).

Cargo Missions: Pre-position supplies, habitats, and infrastructure before human arrival (e.g., NASA's 2033 plan).

Crewed Missions (Opposition/Conjunction Class): Long-duration missions with humans, requiring advanced life support, propulsion, and significant pre-placed assets.

Orbiter Missions: Study Mars from orbit, mapping, atmospheric analysis, and supporting surface operations (e.g., Indian Space Research Organisation's MOM).

Goals & Objectives

Overarching Goals: Discover past/present life, understand Mars's evolution, learn to live and work on other planets, prepare for sustained human presence.

Science Objectives: Identify key measurements, samples, landing sites for specific science campaigns (e.g., searching for biosignatures).

Technology Objectives: Develop and demonstrate new systems for propulsion, life support, surface power, entry/descent/landing (EDL).

Planning & Design Principles

Objective-Based Approach: Start with the "what" (goals/objectives) and work backward to design the "how".

System of Systems: Integrate various elements (launch vehicles, transit habitats, landers, surface assets) into a cohesive architecture.

Constraints: Design within strict mass, power, budget, and schedule limits.

Phased Approach: Utilize precursor robotic missions to pave the way for human exploration (Moon to Mars Strategy).

Risk Management: Address environmental factors (radiation, dust, communication lag) and engineering challenges.

Key Planning Stages & Elements

Define Science & Exploration Goals: What do we want to learn/achieve?.

Develop Mission Architecture: How will we get there and operate (split vs. single launch, propulsion, vehicles)?.

Technology Development: Build necessary tech (e.g., advanced engines, habitats).

Mission Operations: Plan for launch windows, transit, landing, surface activities, and sample return.

Instrumentation & Site Selection: Choose instruments and landing spots to meet objectives.

Collaboration & Public Engagement: Work with partners (international, industry) and build support

NASA Space Mission Life Cycles

NASA project life cycles are divided into two primary phases: Formulation and Implementation.

Formulation Phase (Planning and Technology Validation)

Pre-Phase A: Concept Studies and Mission Definition - Broad ideas are produced and alternatives for missions are analyzed to confirm the mission need and feasibility.

Phase A: Concept and Technology Development - The feasibility of the suggested system is determined, and initial requirements and architecture are developed to establish a baseline for funding.

Phase B: Preliminary Design and Technology Completion - The project is defined in enough detail to establish an initial baseline and mitigate technical and programmatic risks.

Implementation Phase (Building, Launch, and Operation)

Phase C: Final Design and Fabrication - The system design is finalized, and hardware fabrication and assembly begin.

Phase D: System Assembly, Integration & Test, Launch - The system is assembled, integrated, tested, and prepared for launch/deployment.

Phase E: Operations and Sustainment - The mission is actively flown, and data is analyzed and sustained.

Phase F: Closeout - The system is retired after meeting its operational objectives.

This structure allows managers and stakeholders to assess technical progress and make informed decisions at key decision points (KDPs) separating each phase

#33 Re: Exploration to Settlement Creation » WIKI Project Designing for Mars » 2026-01-11 16:23:55

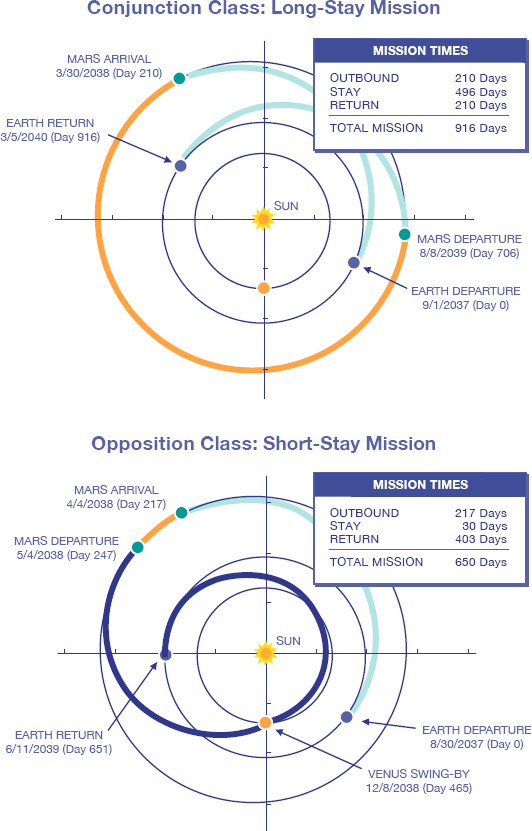

Mars missions for human spaceflight are primarily categorized into two types based on their trajectories and duration: Conjunction-class (long-stay) and Opposition-class (short-stay). Missions are constrained by the relative orbits of Earth and Mars, with launch windows occurring roughly every 26 months (the planets' synodic period).

Conjunction-class missions are generally favored in many studies because they offer significantly more time for surface exploration at a lower fuel cost and reduced crew exposure to the risks of prolonged zero-gravity and deep-space radiation.

Opposition-class missions, while having a shorter overall mission duration, require more advanced propulsion and expose the crew to more time in space and harsher conditions.

Mission Cycles

Launch Windows: Due to the relative orbits of Earth and Mars, launch windows (times of minimum energy transfer) open approximately every 26 months, or 780 days.

Optimal Windows: The specific energy requirements and travel times vary over a larger, roughly 15-year cycle, with certain windows offering the most optimal conditions (e.g., opposition occurring when Mars is closest to the Sun).

Solar Cycle: Mission planning must also consider the approximately 11-year solar cycle. Launching during a solar minimum helps mitigate the risks from solar storms and radiation exposure to the crew

#34 Exploration to Settlement Creation » WIKI Project Designing for Mars » 2026-01-11 16:23:34

- SpaceNut

- Replies: 22

NOT A DISCUSION TOPIC

Project design is the crucial early phase of outlining a project's "why" and "what"—defining goals, scope, resources, deliverables, and success criteria before detailed planning—to create a strategic blueprint for stakeholders, often using visuals like flowcharts to align teams and guide execution. It establishes the conceptual foundation, differing from detailed project planning which focuses on "how" tasks get done.

Key components

• Goals & Objectives: What the project aims to achieve (SMART goals are ideal).

• Scope & Deliverables: Boundaries of the project and tangible outputs.

• Methodology & Strategy: High-level approach and chosen processes.

• Resources & Budget: People, tools, budget estimates, and constraints.

• Success Criteria & KPIs: How success will be measured.

• Risks: Potential issues and mitigation strategies.

Purpose

• Alignment: Gets everyone (team, stakeholders) on the same page.

• Foundation: Creates a clear, agreed-upon path before detailed work begins.

• Visualization: Uses tools (Gantt, Kanban) to make strategy transparent.

• Buy-in: Secures stakeholder approval for the overall direction.

Process steps (simplified)

1. Define the core problem/opportunity.

2. Establish clear goals and SMART objectives.

3. Identify key deliverables and success metrics.

4. Map out required resources and budget.

5. Identify potential risks and constraints.

6. Create visual aids (flowcharts, mockups) to communicate the design.

7. Get stakeholder feedback and approval.

Project design provides the strategic "why" and "what," leading into the detailed "how" of project planning, with outputs like project charters and plans built upon this initial framework

Project design concepts are the foundational ideas, principles, and high-level plans guiding a project, defining its goals, structure, and key features before detailed planning, using visuals like flowcharts and mood boards to align stakeholders on the 'why' and 'what,' ensuring a shared vision for success. Key elements include defining outcomes, identifying stakeholders, exploring options (like sustainability or accessibility), and establishing success criteria, serving as the blueprint for later execution.

Core Components of Project Design Concepts

• Goals & Objectives: What the project aims to achieve (e.g., "sleek and minimalist" for a phone).

• Target Audience & Problem: Who it's for and the problem it solves.

• Scope & Deliverables: What's included and what will be produced (e.g., sketches, prototypes, reports).

• Guiding Principles: Overarching ideas like sustainability, accessibility, or efficiency.

• Visuals & Mood Boards: Mood boards, sketches, flowcharts to convey aesthetics and process.

How They Work

1. Early Stage: Happens before detailed planning or charter development.

2. Blueprint: Creates a broad overview (the "what" and "why").

3. Exploration: Involves generating and evaluating multiple design options.

4. Stakeholder Alignment: Gets buy-in by presenting choices and setting expectations early.

Examples of Design Principles & Concepts

• Product: "Safe and reliable" (car) or "Intuitive user experience" (app).

• Architecture: Integrating local culture, sustainability, or maximizing natural light.

• Process: Using Agile principles or a specific project management methodology

In essence, a project design concept is the strategic "big picture" that transforms abstract goals into a tangible vision, guiding the entire project from its inception to successful completion.

Project design phases generally move from understanding the problem to creating detailed solutions, often covering Programming/Pre-Design, Schematic Design, Design Development, Construction Documents, Bidding, and Construction Administration, though models vary (like the AIA's 5 phases or broader project management cycles). Key stages define scope, develop concepts, produce technical drawings, select builders, and oversee building, ensuring a structured path from idea to reality.

Here's a common breakdown, blending architectural and project management steps:

1. Programming/Pre-Design (Problem Seeking): Define project goals, needs, budget, site analysis, and scope.

2. Schematic Design (Concept): Develop broad concepts, sketches, and basic layouts to explore possibilities.

3. Design Development (Refinement): Flesh out the chosen schematic design with materials, systems, and detailed plans.

4. Construction Documents (Technical Drawings): Create detailed blueprints and specifications for construction.

5. Bidding/Negotiation: Solicit and select contractors.

6. Construction Administration (Building): Oversee the building process, ensuring it matches the design.

Variations & Other Models:

•

Engineering:

Includes research, feasibility, concept generation, detailed design, and production planning.

•

Design Thinking:

Focuses on empathy, defining problems, ideating, prototyping, and testing (Discover, Define, Develop, Deliver).

•

Project Management Lifecycle:

Broader stages like Initiation, Planning, Execution, Monitoring & Control, and Closure.

No matter the model, the goal is to break a complex project into manageable steps, moving from abstract ideas to concrete results

#35 Re: Not So Free Chat » NASA's new leader makes his priorities clear on day one » 2026-01-11 15:35:38

I would be remiss if I did not mention the role that NASA's and DOE's partnership programs as the genesis for the commercialization of a lot of these lab curiosities. Science for its own sake still matters, but so does directed science, aka "engineering", aimed at solving real world problems. NASA helps industry develop the basic "know-how" to retire risk to begin to apply aerospace technologies to the ordinary everyday world that the majority of us inhabit.

Something that others seem to be forgetting when they look at political power, control and funding.

Part of why the locations of of nasa offices and others that do these things.

#36 Re: Not So Free Chat » Politics » 2026-01-11 15:22:03

What only a 3 way split???

#37 Re: Human missions » Interview on Fox News with Jared Isaacman » 2026-01-11 15:16:49

original is in the not so free chat due to politics influence this position as does the others in the senate and house plus the states that have business within them.

So lets stay focused on the interview if possible.

#38 Re: Life support systems » Power generation on Mars » 2026-01-11 15:14:10

Re-read the quote possible power sources as those are all different for how they are configured and while they give power output you will still need to build converting systems to match the devices that you are powering.

Some will require transformers for step-up and some for down before being made use of.

Think about you computer and you cellphone they both have battery but are they the same size in voltage or power. Yes they have converting transformers and circuitry to interface back to you outlet but they do not conform in any other way.

The cables outside the controlled temperatures of a garage or dome will need different specifications as the cold will make some materials brittle.

So no there is no one forced standard

So the number of watts for creation is not even known?

No list of equipment to make use of those watts?

How much is to be fore personal use?

No list of stuff needing heavy load powered versus items needing next to nothing?

Each building and sections there in are going to needed specifics to solve to what each will need to have configured for use and connection layout.

#39 Re: Life support systems » Power generation on Mars » 2026-01-11 14:50:53

They are earth safety standards for consumer use...

The specifics are based on wiring diagramming of how the power is to be used which is from the interface circuit breaker box system that you should be aware of.

For a Mars garage, power systems need reliability in dust and cold, likely combining solar arrays with advanced batteries (like Lithium-ion or supercapacitors) for peak loads and consistent energy, supplemented by Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generators (RTGs) or future Nuclear Fission Reactors for baseline power, especially during dust storms and night, alongside energy storage and distribution systems (PMAD) to manage variable demands for tools and habitat functions.

Primary Power Sources

Solar Arrays (Photovoltaics): Efficient when sunlight is available but challenged by dust accumulation and reduced intensity during Martian winter/storms, requiring regular cleaning.

Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generators (RTGs): Use natural decay of plutonium to generate continuous heat and electricity, providing reliable, long-term power independent of sunlight, excellent for baseline needs.

Nuclear Fission Reactors: For larger, sustained power needs (like industrial processes or larger habitats), small fission reactors offer high power output but require significant shielding for radiation.

Energy Storage & Management

Batteries: Rechargeable lithium-ion batteries (like those used on rovers) handle peak power demands, while advanced alternatives like graphene supercapacitors offer faster charging and wider temperature tolerance.

Power Management & Distribution (PMAD): Essential systems to convert, condition, and distribute power from sources to loads, handling start-up, shutdown, and dynamic events.

Supporting Technologies

Waste Heat Utilization: Nuclear systems produce excess heat, which can be converted to electricity or used for habitat/regolith heating, improving efficiency.

In-Situ Resource Utilization (ISRU): Solar concentrators could use sunlight for heating and 3D printing/sintering, potentially reducing reliance on pure PV cells.

Advanced Motors/Generators: Electric motors are preferred over combustion engines due to simplicity; next-gen storage like supercapacitors could revolutionize rapid power delivery.

Considerations for a Mars Garage

Dust Mitigation: Systems to clean solar panels and protect equipment from fine dust are crucial.

Thermal Management: Dealing with extreme cold (using waste heat or electrical heaters) is vital for equipment and battery health.

Scalability: A mix of sources (solar for peak, nuclear for baseline) offers the best resilience, from small tools to large fabricators

As you can see they are not standard

#40 Re: Not So Free Chat » NASA's new leader makes his priorities clear on day one » 2026-01-11 14:45:51

I am very enthusiastic with the appointment of Jared Isaacman as NASA Administrator!

Here's a link to this excellent interview!

Sorry that the name was not in my original title but we know this as being more politically delivered than anything else.

#41 Re: Human missions » Why Artemis is “better” than Apollo. » 2026-01-11 14:43:26

That's going to happen when management tries to be engineers looking at balance sheets rather than performance.

So which shield type is this one as I remember the original PICA version was dismissed for the honey combo hand inserted materials to which this one makes me wonder...

#42 Re: Human missions » Why Artemis is “better” than Apollo. » 2026-01-11 14:39:53

The odds favor their survival, but the lethal uncertainty is nowhere near zero. Initially, the excuse was eliminating the skip and just going for direct entry. I do not see anything of that plan in the recent stories. This reminds me eerily of Challenger and Columbia.

I am still disappointed seeing the entire debate framed only as "fly what you have" vs "total redesign". Total redesign is NOT required, all they need to do is go back to the labor-intensive hand-gunned heat shield. There is NO REDESIGN associated with that! They already HAVE that design! They already flew it!

Doing that would enable them to work out how to cast those tiles with the hex cores in the them, and fly such a thing, even as a subscale test article, to see it actually work right. I already showed how to do that revised processing with an extrusion press, here on these forums, and I already sent that idea to them via a contact I knew within NASA, who has since retired. I NEVER EVER heard back from their heat shield people, to whom my contact forwarded my materials. "Not invented here" is a real flaw shared by lots of big organizations!

But it would definitely work, because the fibrous nature of the charred hex helps tie the otherwise weak carbon char together. It's a composite material that is better than just the carbon char from the polymer alone. I know that because of my experience with ablatives in ramjets and solid rockets. If you cannot reinforce the char, it goes away too quickly, in one fashion or another. Which experience goes way beyond sample testing in an arc jet tunnel, and running CFD codes that usually do not deserve to be believed, without confirmation testing! I'm talking real burn experiences with real motors and engines here!

The Artemis 1 failure already proved that fiber reinforcement contention of mine! The only difference between Artemis 1 and the first Orion that flew was that they deleted the hex to cast the tiles instead of hand-gunning the polymer into a hex core already attached to the capsule, like Apollo. Which is what flew on the first Orion. That's NOT a FULL re-design of anything, it's only a variation on the cast tile processing they now prefer (at the risk of the crew's lives, I might add, if they don't do something to reinforce that char).

GW

#43 Re: Meta New Mars » Housekeeping » 2026-01-11 13:16:38

off topic solving of potential failures within a project is just what the fishbone is for..

Fishbone theory, or the Fishbone Diagram (also known as an Ishikawa Diagram or Cause-and-Effect Diagram), is a visual tool for root cause analysis that maps out potential causes of a problem in a fish-skeleton-like structure, helping teams brainstorm, categorize, and identify underlying issues, not just symptoms, for better problem-solving in quality control and management. The problem is the "head," and major causes branch off the "backbone" as "ribs," with sub-causes extending further, revealing hidden linkages and process bottlenecks for future improvements.

you have you own topic of import everything to do you process within to make the garage that you want on mars.

I have already shown that import everything on the first connex box transport is not sustainable as the equipment gets larger to perform the task of building increases.

#44 Re: Human missions » Why Artemis is “better” than Apollo. » 2026-01-11 11:12:32

For GW Johnson...

https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/technolo … e130a&ei=8

I think this is the best way to preserve items that would disappear over time.

The story at the link above reports on a personal review of the heat shield for Artemis II by the new NASA director.

(th)

NASA chief puts Orion heat shield through final go/no-go check

On the eve of the first crewed flight of the Artemis program, NASA’s top leadership has zeroed in on a single, unforgiving piece of hardware: the Orion capsule’s heat shield. The final go or no-go review of that system is not just a technical milestone, it is a public test of whether the agency has truly learned from the scorching lessons of Artemis I and is ready to send astronauts back toward the Moon.

By personally scrutinizing the Orion heat shield before Artemis II, the new NASA chief is signaling that the agency’s confidence must be earned, not assumed. The outcome of that review will shape when the mission flies, how the crew returns, and how the public judges NASA’s willingness to confront uncomfortable risks in full view.

From char loss mystery to root cause

The scrutiny now focused on Orion’s heat shield began the moment the uncrewed Artemis I capsule was pulled from the Pacific and hauled back to shore. After NASA recovered the Orion spacecraft and transported it to NASA’s Kennedy Space Center, engineers found that parts of the charred layer on the ablative shield had come off in ways they did not fully predict, a surprise for a system designed to burn away in a controlled fashion during reentry. That discovery triggered a long investigation into why chunks of material were shedding, and whether the pattern hinted at a deeper design flaw in the thermal protection system that guards the crew module.Investigators eventually traced the problem to how the material behaved under the specific heating and airflow conditions of the Artemis I trajectory, rather than to a single manufacturing defect or obvious structural crack. NASA has described how the charred layer on Orion’s base heat shield experienced unexpected char loss, prompting teams to dissect the shield, model the aerothermal environment, and compare test data with flight telemetry. That work set the stage for the current go or no-go decision, because it forced NASA to decide whether the anomaly could be bounded with analysis and minor tweaks, or whether a more invasive redesign was needed before putting people on board.

Why Artemis II depends on a single shield

The stakes of that decision are clear when I look at what Artemis II is supposed to do. The mission will send a crew of four, including Christina Koch, on a loop around the Moon and back to Earth, exposing Orion to a high-speed reentry that is only slightly less punishing than a direct lunar return. Koch and the other members of the Artemis 2 crew are eager to launch on their mission, but their path home runs straight through the same thermal environment that stripped away char on Artemis I, and any uncertainty about the shield’s performance becomes a direct question about crew safety.NASA has already acknowledged that the next flight is a crucial stepping stone toward a sustained lunar presence and, eventually, the kind of deep-space expeditions needed for crewed Mars missions. The agency’s decision to proceed with Artemis II using the existing Orion heat shield design, rather than ripping it out, followed an extensive review of the Artemis I data and a formal update to the broader Artemis flight plan. That choice effectively ties the schedule for returning humans to lunar orbit to the confidence engineers and leadership can place in a single, upgraded but not fundamentally redesigned shield.

Skip entry, schedule pressure, and a narrow launch window

The technical debate around Orion’s protection system is inseparable from the way the capsule comes home. For Artemis I, NASA used a “skip entry” profile in which Orion dipped into the atmosphere, then briefly bounced back out before making its final descent, a maneuver that spreads heating over a longer path but also creates complex aerodynamic loads. NASA traced the problem in part to Orion’s skip entry trajectory, noting that the pattern of char loss matched the phases when the capsule was skimming the upper atmosphere and then diving back in, which is why the same profile for Artemis II has drawn so much attention from engineers and outside analysts alike.All of this is unfolding against a tight but flexible launch window that could open as soon as early February. NASA’s Artemis II mission is currently targeted to launch in February, with officials describing a window that stretches from Feb. 6 to April 10 and is broken into several distinct periods of possible liftoff opportunities. Local coverage has underscored how the mission, updated at 10:24 PM EST, will be the first time astronauts fly around the Moon since Apollo, and that schedule pressure is now colliding with the need to be absolutely certain about the heat shield’s behavior on another skip entry.

nside the new NASA chief’s go/no-go moment

Into this mix has stepped a new NASA administrator, Jared Isaacman, who has made a point of personally engaging with the Orion heat shield issue. In a detailed review session described by space reporter Eric Berger, Isaacman pressed engineers on what went wrong with Artemis I and what had changed for Artemis II, before ultimately expressing full confidence in the system. That level of openness and transparency is exactly what should be expected of NASA, Berger wrote, noting that Isaacman had only been sworn in on December 18 when he convened the review that would effectively serve as the final go or no-go check for the shield, a moment captured in Jan coverage of the meeting.What stands out to me is how candid the internal conversation appears to have been. According to a detailed account shared by one attendee, the NASA team spent most of the session walking through charts and models before, toward the end of the meeting, agreeing to discuss something that no one really liked to talk about: the residual risk that cannot be engineered away. One of the NASA engineers said that even with all the analysis, there is still a nonzero chance of unexpected char behavior, a comment that surfaced in a However detailed community write-up of the review. Isaacman’s decision to accept that residual risk, while insisting on continued testing and monitoring, is the essence of a go call in human spaceflight.

Rollout, wet dress, and what still worries engineers

Even as the heat shield debate plays out in conference rooms, the hardware for Artemis II is moving toward the pad. NASA plans to roll out the Space Launch System rocket for the mission on Jan. 17, a key step that will lead into a full “wet dress rehearsal” where teams load the core stage and upper stage with more than 700,000 g of cryogenic propellants, roughly 2.65 m liters, and run through the countdown. During wet dress, teams demonstrate the ability to load more than 700,000 g of supercold fuel without leaks or valve issues, a rehearsal that must succeed before anyone worries about the heat shield’s performance on the way home.Behind the scenes, though, some specialists remain uneasy about how much of the Artemis I anomaly has been retired by analysis alone. A detailed video breakdown posted in Jan by an independent analyst revisited the Orion heat shield investigation and walked through what char loss really means for the structure underneath, highlighting how localized material shedding could, in a worst case, expose underlying layers to higher heating than expected. That follow-up on Orion underscored that while NASA’s official line is that the shield is safe for flight, there is still a healthy debate in the technical community about whether the current design has enough margin for the long-term Artemis roadmap.

Delay debates, outside critics, and the politics of risk

The path to this moment has already included one major schedule reset. In Dec, NASA announced that it would delay the next flight of the Aremis program, Artemis 2, pushing the mission back from its earlier target so engineers could fully understand the heat shield behavior and other systems. That decision, dissected in a widely viewed explainer on why NASA is not fixing the heat shield on Artemis II, made clear that the agency preferred to accept a longer gap between flights rather than rush a redesign that might introduce new unknowns, a tradeoff that was laid out in detail in a NASA-focused analysis of the delay.Critics have also questioned whether the nomination of Jared Isaacman, a billionaire pilot with his own commercial spaceflight ambitions, has overshadowed the technical issues around Orion. In Dec, one commentator argued that the Isaacman nomination risked pulling attention away from the hard engineering questions and toward personality-driven coverage, urging viewers on Thursday to focus instead on the new information about the heat shield and its test history. That perspective, shared in a detailed Thursday breakdown of the nomination, reflects a broader tension: NASA must balance the political optics of bold leadership with the unglamorous work of resolving char patterns and thermal margins.

Crew confidence and the long road back to the Moon

For the astronauts assigned to Artemis II, the heat shield debate is not an abstract engineering exercise. Christina Koch has spoken about how she and her crewmates are preparing for a mission that will test not only Orion’s systems but also the procedures and teamwork needed for later landings, and Koch and the other members of the Artemis 2 crew are eager to launch on their mission as soon as NASA gives the final green light. Their confidence rests on the assurance that the same shield which protected an uncrewed capsule through a skip entry will do the same with four people strapped inside, a point underscored in a feature on how Koch and the crew are training for the unknowns they might encounter around the Moon.NASA’s own messaging has tried to thread the needle between caution and ambition. Agency leaders have emphasized that the Artemis architecture, including Orion’s heat shield, is being built not just for a single lunar flyby but for a series of increasingly complex missions that will eventually support long-duration stays on the surface and, further out, crewed Mars expeditions. Local television coverage in Jan, updated by reporter Meghan Moriarty and reporter Hayley Crombleholme, has highlighted how the Artemis II mission to launch in February is framed as a historic return to deep space that must still clear a rigorous safety bar before liftoff. That framing, captured in a Meghan Moriarty segment, shows how the final go or no-go on the heat shield has become a proxy for the public’s trust in NASA’s entire lunar strategy.

What the final call will really decide

As the rollout date approaches, the agency is also refining its launch opportunities and contingency plans. NASA has broken the Artemis 2 launch window into three periods, each with a restricted set of possible liftoff times that balance lighting conditions, communications coverage, and the geometry of the return corridor. That structure, outlined in a Jan update on how Artemis 2 will move to the pad and aim for dates between Feb. 6 and April 10, underscores how tightly the mission’s trajectory, including the skip entry, is woven into the calendar.In parallel, public-facing explainers have reminded viewers that the heat shield will face its biggest test yet when Orion comes back from the Moon with people on board. One recent overview noted that the same skip entry profile that contributed to char loss on Artemis I will again be used to manage g-forces and heating, and that NASA traced the earlier problem in part to that trajectory while still concluding the system is safe for flight. That assessment, summarized in a Jan report on the upcoming mission, makes clear that the final go or no-go check by the NASA chief is less about discovering a new flaw and more about affirming that the agency is willing to own the residual risk it has already mapped.

#45 Re: Life support systems » Power generation on Mars » 2026-01-11 10:48:23

For SpaceNut re electrical fittings in the garage on Mars.

A solution is to decide upon a single electrical system for Mars.

This would require negotiation before any Nation lands on Mars.

We have international standards for many aspects of modern society.

Setting up standards for Mars seems possible before the kind of mess you've described occurs.

In the mean time, you have the power to simply declare what fixtures your be, and continue with your garage plan.

(th)

Another fishbone topic of power

And yet with standards we still power things with different battery voltages, transmit AC power in 50 and 60 cycles, Single phase AC with ranges, Multi phase is a number of phase angle relationships, high voltage DV and AC transmission lines, ect.. Mars will use all as we do here.

This brings up the next fishbone topic Power Distribution by pipelines on Mars.

#46 Re: Science, Technology, and Astronomy » Robots becoming useful... » 2026-01-11 10:46:03

For SpaceNut re Garage Design for Mars...

http://newmars.com/forums/viewtopic.php … 65#p237065

Because of the risks to humans, would it make sense to keep the humans in a protected habitat with electronic access to the garage?

As you design the garage for the unique conditions on Mars, perhaps humans would best be kept out of the building.

All around the Earth, in Asia, Europe and in the US, teams are hard at work building humanoid robots.

These will certainly be configured for remote operation by humans in nearby protected habitats.

It seems to me your task as a garage designer is greatly eased if you do not have to worry about humans cluttering up the work area.

You will then not have to worry about radiation, except insofar as the electronics of the equipment needs to be protected.

Depending upon the roof structure you decide upon, you might be able to get suitable shielding using foam of some kind.

Plastic foam can be made on Mars. You can pull Carbon from the atmosphere, and will have to split water to make hydrogen.

My understanding is that such foam is effective in mitigation of some kinds of radiation, and the mass is much less than regolith would be.

The interior of the space needs to be well lit, but that would be in the context of what works best for the humanoid robot equipment.

Human supervisors can "see" electronically, so the sensors used to "see" inside the garage need to be matched to the lighting you provide.

Here's a detail I'll bet not too many folks have thought about. What electrical fixtures will you specify for this work space?

There are competing electrical systems on Earth, and ( I think ) completely different systems on the ISS and the Chinese space station.

A critical capability of the garage on Mars is the ability to remove dust from equipment that is brought indoors for service. What systems will you specify for that important function. Electrostatic charge is likely to be a problem. I wonder how the rover designers deal with it?

(th)

Your post is a fishbone for the topic of how to trouble shoot a dead vehicle that is in need of repairs for a specific type of equipment since all the types are not going to have universal computer codes for what might be wrong with it. Same as current car and trucks.

#47 Re: Meta New Mars » Housekeeping » 2026-01-11 10:44:33

Another fishbone topic of power

And yet with standards we still power things with different battery voltages, transmit AC power in 50 and 60 cycles, Single phase AC with ranges, Multi phase is a number of phase angle relationships, high voltage DV and AC transmission lines, ect.. Mars will use all as we do here.

#48 Re: Meta New Mars » Housekeeping » 2026-01-11 09:14:29

Your post is a fishbone for the topic of how to trouble shoot a dead vehicle that is in need of repairs for a specific type of equipment since all the types are not going to have universal computer codes for what might be wrong with it. Same as current car and trucks.

#49 Re: Exploration to Settlement Creation » Designing Mars equipment garage » 2026-01-11 08:41:42

Out of that area of the the constructed garage we will need to have when a drawing of layout is performed offices areas to keep records or logs of equipment work and materials used which will also require dedicated software and record keeping for each member doing the work.

The set aside parts material area is also not really defined yet, tools types and methods to store where in the shop.

Previous posts also has had much added to them.

post 13 Quonset hut or in this case repurposed starship stainless is a shallow circular structure 150m diameter with height as 25 meter is required for the taller equipment needing crane support work of 15 meters above the floor.

outer wall height must clear the top of the equipment so as to be able to enter the structure.

Whether the structure is a square or dome or any other the items will require a height of 20 plus meters with a minimum of diameter of 100meters.

#50 Re: Meta New Mars » Housekeeping » 2026-01-11 08:14:37

Post still can be edited by the owner of them as tagged with the user id. even when split or moved to new categories or titles.