New Mars Forums

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

Announcement

#26 2022-06-27 06:12:49

- Mars_B4_Moon

- Member

- Registered: 2006-03-23

- Posts: 9,776

Re: Interstate 80 San Francisco Salt Lake City Water Pipeline

Could nuclear desalination plants beat water scarcity?

https://www.bbc.com/news/business-61483491

Solar partly powering world’s largest reverse osmosis desalination plant

https://www.pv-magazine.com/2022/06/23/ … ion-plant/

According to ACWA, the facility is 44% largest than the world’s current largest reverse osmosis (RO) plant in terms of capacity. It is able to meet water demand for more than 350,000 households.

Last edited by Mars_B4_Moon (2022-06-27 06:13:41)

Offline

Like button can go here

#27 2022-06-27 06:45:15

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 24,092

Re: Interstate 80 San Francisco Salt Lake City Water Pipeline

For Mars_B4_Moon re #26

Thanks for the reports/links you provided to progress on desalination, and specifically solar powered ones!

While desalination of Pacific Ocean water is not a ** primary ** objective of the Interstate 80 pipeline, it certainly ** is ** a secondary objective.

The ** primary ** objective is to refill the Great Salt Lake.

Please keep a watch for any news you might run across, about efforts to create a pipeline from California, across Nevada and Utah, to refill the Great Salt Lake with sea water.

This is not (primarily) a technical challenge. It is almost entirely a social problem. The objective of refilling the Great Salt Lake has no obvious economic benefit, so ordinary capitalism would appear not the best fit as a driver of the effort. On the other hand, once funds are raised, and approvals are granted, then capitalists will have a field day completing to land the contracts to do the work.

The raising of funds for this purpose is similar to rebuilding towns and cities devastated by natural disasters. The difference is that this is a ** slow ** moving natural disaster.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#28 2022-06-27 18:09:54

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,545

Re: Interstate 80 San Francisco Salt Lake City Water Pipeline

While not on the route 80 corridor the Salton Sea is still in the news as to push for it to be refilled as well.

There is a great push on as well to get fresh water to the colorado as well but that is for another topic.

All in all, it comes back to how much and how long to build it and then you have the environmental issues that if built along existing corridors cuts down on the paperwork.

Offline

Like button can go here

#29 2022-06-27 18:31:56

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 24,092

Re: Interstate 80 San Francisco Salt Lake City Water Pipeline

For SpaceNut re Salton Sea vs Great Salt Lake ....

Thanks for pointing out similarities and differences between the two situations.

Salton Sea has major advantages ... it is below sea level, and it is (comparatively) close to ** two ** ocean coastlines.

A simple ditch would fill the Salton Sea, if water is pumped to the high point of the elevation between.

An alternative is an underground channel, which could be bored in a straight line.

However, ** this ** topic needs to stay on track. Anyone who spots news about politicians talking about the Great Salt Lake pipeline is welcome to post it here.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#30 2022-06-29 09:29:50

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 24,092

Re: Interstate 80 San Francisco Salt Lake City Water Pipeline

This letter writer is proposing an underground pipeline from the Pacific Ocean off California, to the Salton Sea.

This is actually a reasonably practical idea ... the various proposals for Hyperloop trains envision tunnels of this length and greater....

https://www.yahoo.com/news/yes-lets-imp … 37839.html

The Desert Sun

Yes, let's import water for the Salton Sea — but from the Pacific Ocean

Reader submissionsWed, June 29, 2022 at 9:00 AM

Several birds forage and fly near a rocky outcropping on the southern end of the Salton Sea in 2005.

Re: Feliz Nunez's Sunday Valley voice on importing water for the Salton Sea.

Right on, Ms. Nunez. What are we waiting for?

The underground Delaware Aqueduct was constructed between 1939 and 1945 (wartime) and supplies New York City with 50-80% of its water. It is 85 miles long, the world’s longest tunnel.

I understand that it is about 75 miles from the Pacific Ocean to the Salton Sea. Underground! No worries about Mexican property rights, jurisdiction or international friction that might result from an overland import via canals from the Sea of Cortez. Across Southern California, there would be little disruption to existing U.S. highways, urban areas, agriculture or natural habitat.

Only massive amounts of water will permanently resolve the myriad of problems vexing the Salton Sea. The Pacific Ocean is rising and could use some drainage. Plus providing a water source for lithium extraction. Win, win, win.

This is one of the projects being evaluated by UC Santa Cruz. I’m rooting for this one. What are we waiting for?

Kay Wolff, La Quinta

This article originally appeared on Palm Springs Desert Sun: Yes, let's import water for the Salton Sea — but from Pacific Ocean

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#31 2022-06-29 21:53:11

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,545

Re: Interstate 80 San Francisco Salt Lake City Water Pipeline

The response will be interesting to create an underground system to refill the sea with.

Offline

Like button can go here

#32 2022-07-06 11:24:15

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 24,092

Re: Interstate 80 San Francisco Salt Lake City Water Pipeline

Here is an update on the condition of the Great Salt Lake...

For Mars_B4_Moon ... please keep a watch for any signs the idea of importing sea water from the Pacific is staring to gain currency...

https://www.yahoo.com/news/great-salt-l … 55733.html

Tue, July 5, 2022 at 5:05 PM

SALT LAKE CITY (AP) — The Great Salt Lake has hit a new historic low for the second time in less than a year as the ongoing megadrought worsened by climate change continues to shrink the largest natural lake west of the Mississippi.Utah Department of Natural Resources said Monday in a news release the Great Salt Lake dipped Sunday to 4,190.1 feet (1,277.1 meters). That is lower than the previous historic low set in October, which at the time matched a 170-year record low.

Lake levels are expected to keep dropping until fall or winter, the agency said.

Dwindling water levels at the giant lake just west of Salt Lake City puts millions of migrating birds at risk and threatens a lake-based economy that’s worth an estimated $1.3 billion in mineral extraction, brine shrimp and recreation. The expanding amount of dry lakebed could also send arsenic-laced dust into the air that millions breathe, scientists say.

The state's Republican-led Legislature is trying to find ways to reverse the trend, but it won't be easy. Water has been diverted away from the lake for years for homes and crops in the nation’s fastest-growing state that is also one of the driest.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#33 2022-07-08 12:08:31

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 24,092

Re: Interstate 80 San Francisco Salt Lake City Water Pipeline

For SpaceNut re development of this topic ...

Thanks (again) for the tip about Yellowstone being in the line of Interstate 80 ...

I discovered that Interstate 80 goes right near (if not through) Yellowstone.

The issue of who owns what is going to become significant.

Pulling energy (thermal energy to be specific) out of the hot spot under Yellowstone would qualify as a Homeland Security issue, so if the appropriate departments of the US government can be enlisted, along with the Governors of the respective states, the project could be commissioned as an Army Core of Engineers project, like a river management structure or any of a great number of public works.

The Department of Energy would be an agency with an interest, and NASA is already engaged because of the study they funded.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#34 2022-07-09 06:46:49

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 24,092

Re: Interstate 80 San Francisco Salt Lake City Water Pipeline

Today's Internet feed included this report on the deterioration of the Great Salt Lake..;.

Should the Great Salt Lake continue to dry up, a state assessment from 2019 found the economic toll to Utah could span from $1.69 billion to $2.17 billion per year and result in over 6,500 job losses. Over the course of 20 years, these costs could be as high as $25.4 billion to $32.6 billion, the assessment emphasizes.

The lake contributes an estimated $1.32 billion to Utah's annual economy, according to a 2012 report that the assessment references. However, this estimate is in 2010 dollars. When adjusted for inflation, the estimate would equate to at least $1.77 billion.

The health of the nearly 3 million people who live around the Great Salt Lake will also be impacted, with exposed lakebed dust containing levels of arsenic.

"Every single measurement that I took out on the Great Salt Lake had higher arsenic concentrations than would be recommended by the Environmental Protection Agency," Kevin Perry, an associate professor in the Department of Atmospheric Sciences at the University of Utah who has studied the impacts on the lake, told Wadell in 2021. To answer the question of just what was in the dust, he biked out to collect samples every 500 meters across the exposed lakebed.

Even if the dust didn't contain arsenic, the combination of wind and dust would still pose a health hazard if the concentration was high enough, Perry added.

FILE - Mirabilite spring mounds are shown at the Great Salt Lake on May 3, 2022, near Salt Lake City. The Great Salt Lake has hit a new historic low for the second time in less than a year. Utah Department of Natural Resources said Monday, June 5, 2022, in a news release, the lake dipped Sunday to 4,190.1 feet. (AP Photo/Rick Bowmer, Pool, File)

Earlier this year, lawmakers in Utah, desperate for a solution to the worsening problem, voted to commission a study on the feasibility of piping in water from the Pacific Ocean to replenish the Great Salt Lake.

“Dire times call for dire measures,” Utah Representative Carl Albrecht said at the time, according to a report by KUTV. “Water’s going to become pretty valuable for drinking, sewer, and irrigation. We run pipelines all over this country full of gas and oil and whatever.”

For Taylor, the longtime resident who shot the drone footage, urgency is top of mind. "Something needs to be done soon," Taylor said. "Or the lake will be a hazard more than a good thing."

Meanwhile, other lakes and reservoirs across the West have also suffered the consequences of harsh drought and water diversions.

In late June, water levels at Lake Mead, a reservoir formed by the Hoover Dam that sits between Arizona and Nevada, reached the lowest point since the lake was filled in the 1930s. The reservoir is the nation's largest by volume.

Lake Mead and its declining water levels gained national attention after the federal government formally declared a water shortage in August 2021 for the first time since its construction. From June 2021 to June 2022, the water levels at the reservoir dropped an additional 26 feet, and water levels are projected to continue to drop until the wet season begins in November, according to the Bureau of Reclamation.

This photo taken Monday, April 25, 2022, by the Southern Nevada Water Authority shows the top of Lake Mead drinking water Intake No. 1 above the surface level of the Colorado River reservoir behind Hoover Dam. The intake is the uppermost of three in the deep, drought-stricken lake that provides Las Vegas with 90% of its drinking water supply. (Southern Nevada Water Authority via AP)

The receding shoreline hasn't exposed arsenic-laden soil, but it has revealed an intake valve, at least two sets of human remains and, more recently, a previously sunken World War II-era boat.

The Higgins landing craft that once sat 185 feet below the surface is now nearly halfway out of the water less than a mile from Lake Mead Marina and Hemingway Harbor, The Associated Press reported.

While over 1,000 of these crafts were deployed at the Battle of Normandy on June 6, 1944, or D-Day, this boat had once been used to survey the Colorado River. It was sold to the marina before sinking, the dive tours company Las Vegas Scuba told the AP.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#35 2022-07-19 10:43:19

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 24,092

Re: Interstate 80 San Francisco Salt Lake City Water Pipeline

For SpaceNut ....

Ongoing developments in the Phoenix have revealed a solution to the Great Salt Lake challenge....

It appears quite likely that shipments of tank car lots of Pacific ocean water to the Great Salt Lake are possible, funded by US taxpayers.

A non-profit organization needs to be the vehicle for this pass-through opportunity.

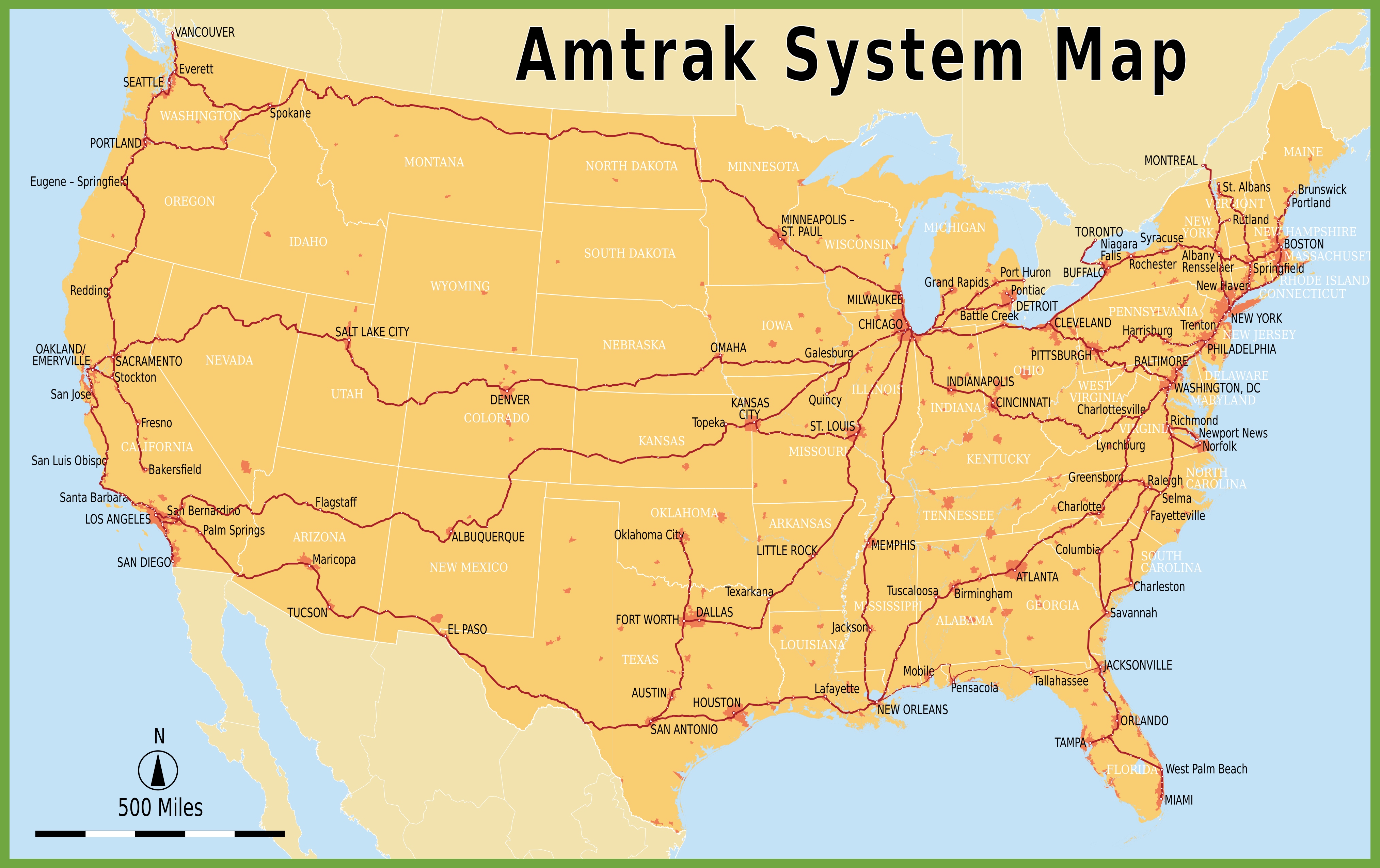

The non-profit (of which there are a great number in Utah and else where) would solicit tax-deductible donations to fund shipments of Pacific Ocean water via existing road and rail systems for delivery to the Great Salt Lake.

The service could begin immediately, following completion of the paperwork.

The funds would flow to the individuals who would transport the water from source to destination.

Thus, good paying jobs in the transport industry would become available, and as donations swell, the number of those jobs would increase.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#36 2022-07-19 20:05:09

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,545

Re: Interstate 80 San Francisco Salt Lake City Water Pipeline

Offline

Like button can go here

#37 2022-07-19 21:04:16

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 24,092

Re: Interstate 80 San Francisco Salt Lake City Water Pipeline

For SpaceNut re #36

Thanks for the link to a report on work being done to keep Interstate 80 in full operation. The mention of the railroad crossing was particularly interesting!

I'll let you know promptly if anything happens in response to recent inquiries.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#38 2022-07-21 19:18:31

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,545

Re: Interstate 80 San Francisco Salt Lake City Water Pipeline

https://www.up.com/aboutup/reference/maps/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Union_Pacific_Railroad

Many train companies kept the tracks at different widths so as to control the transport via trains.

Offline

Like button can go here

#39 2022-07-21 19:48:40

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 24,092

Re: Interstate 80 San Francisco Salt Lake City Water Pipeline

For SpaceNut re #38 ...

Thanks for the map and for links to ** more ** maps, including one that shows a Union Pacific line to Nogales from Phoenix.

Somewhere in one of your posts you mentioned track gauge .... The Soviet Union is famous for having set their rail network to NOT be compatible with Europe, to slow down invaders. In literature I've seen in recent days, I understand that in recent years, Mexico has standardized on the same gauge as the US. This was probably encouraged by NAFTA, or perhaps the decision was made before NAFTA. Either way, cars/engines can travel from Mexico to the US and back without difficulty.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#40 2022-07-22 17:09:00

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 24,092

Re: Interstate 80 San Francisco Salt Lake City Water Pipeline

For all ... the distance to be covered by a pipeline to refill the Great Salt Lake is on the order of 700 miles.

Somewhere along the line I picked up an incorrect number, but a friend pointed out the error.

I'll go back through the posts to find any instance of the incorrect number, and update it.

11 hr 53 min (735.9 mi) via I-80 E

Above is the distance between San Francisco and Salt Lake City.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#41 2022-07-23 11:18:36

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 24,092

Re: Interstate 80 San Francisco Salt Lake City Water Pipeline

The article at the link below provides a short overview of the challenges caused by sea water corrosion on sea going vessels:

https://www.shshihang.com/corrosion-and … -pipeline/

The issue was brought as a concern by the gent who lives in Phoenix, and who has taken an interest in the Great Salt Lake pipeline, in addition to the (proposed) Sea of Cortez to Phoenix pipeline.

While the leading proposal for the Phoenix pipeline would ship desalinated water North, an attractive alternative is to ship sea water north and handle all the issues of desalination and harvesting of valuable atoms in the US.

Plastic pipes are manufactured in large diameters these days, so those might be fitted inside traditional iron/alloy pipes to reduce corrosion.

The initial expense would be greater than for a traditional pipe, but the long term savings may justify the investment.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#42 2022-07-24 10:02:59

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 24,092

Re: Interstate 80 San Francisco Salt Lake City Water Pipeline

https://www.yahoo.com/news/engineer-her … 05563.html

This analysis of the Mississippi pipeline idea includes review of earlier proposals.

The Desert Sun

As an engineer, here's how I look at the idea of pumping water from Mississippi to the WestJohn Homer

Sun, July 24, 2022 at 8:01 AM

A bulldozer clears a descent path to move equipment down to the level for drilling operations as workmen start excavations for building the Channel Tunnel outside Calais, France, Nov. 17, 1973

At an age when my classmates were fascinated with dinosaurs or playing Cowboys and Indians, I picked up a book titled “Engineers’ Dreams” and was hooked. Thus began a lifelong interest in projects associated with engineering concepts about improving our world.

The author, Willy Ley, sketched the outlines of some large civil projects including the development of the Channel Tunnel connecting Britain with France. Of course, the tunnel has been in use for 28 years. He also explored ideas for generating electricity. With solar and wind power leading the way, every one of his generation schemes has seen significant development since.

Given my interests, I was drawn to a recent letter in The Desert Sun proposing to solve the shortage of water in the Southwest by bringing water from the Mississippi River.

This is not the first proposal to find water for the Southwest. One such scheme, made more than 50 years ago, would have brought water from Alaska and Canada to feed into the Columbia, Missouri, and Colorado River systems. Aside from international political and environmental considerations, the proposal was sunk by a forecast return on investment of about 5 cents for every dollar invested. I wondered would the Mississippi water scheme have a better return?

Additionally, how would I register the feasibility of this scheme against the author’s contention that two reference projects — the California Aqueduct and the Alaska Pipeline — represented far more difficult projects than he envisioned this plan to be. Marshalling a few facts challenged that supposition.

The proposed flow of 250,000 gallons/second represents a lot of water. Converting it into a more normal engineering unit, this would represent about 32,000 cubic feet/second (CFS). That happens to be about the same rate of flow as passes through the generating turbines at Hoover Dam at full capacity. In the original letter, this flow was correctly calculated as the amount of flow necessary to fill Lake Power in one year. Even at today’s record low level, Lake Power is not empty. Lesser flows could reduce the costs and difficulty of the project while still providing significant benefits.

The Alaska Pipeline is a significant project. It involved construction, in forbidding conditions, of a 48-inch diameter pipeline about 800 miles long. The peak capacity flow rate is 2 million barrels per day, or about 100 CFS. So, as a comparison, pumping the proposed volume of water from the Mississippi would involve a distance approximately twice as long for a flow about 320 times as great.

The California Aqueduct involves a peak flow of 13,000 CFS over a distance of about 450 miles. As proposed, this Mississippi diversion project would involve 2½ times as much water over a distance nearly four times as long.

One big challenge of the California Aqueduct is pumping water to a height of 1,926 feet, which requires massive pumping equipment. Our Mississippi diversion scheme has a net difference in elevation of 3,700 feet from New Orleans to Lake Powell, or a terminus nearly twice as high as the highest point in the California Aqueduct. This last difference is especially significant because the fall from 1,926 feet to near sea level could, in theory, be used to generate some power to offset the pumping power requirement. That option is not fully available in pumping to 3,700 feet.

The peak elevations required for pumping the water are likely much greater than the net difference of 3,700 feet. If we discount the higher elevations the water has to be pumped to, we still have to provide the power to raise the water to 3,700 feet. Using the power plant at Hoover Dam as a reference, this would require about 12,000 megawatts of pumping power.

The power requirement of the flow would require at least the equivalent capacity of about 5½ times the power output of the new Plant Vogtle nuclear facility in Georgia. Plant Vogtle has been estimated to cost over $28 billion. Thus, our water pumping scheme could incur a cost of $150 billion for the power plants alone.

“Wait you say, what about wind power instead of nuclear? Surely that would be cheaper.” Yes, it would, but there are, of course, challenges. A wind turbine cannot reliably produce power 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. So the installed wind power capacity would be greater than the current capacity from the 150 wind farms in Texas.

As a nation, we have seemingly lost our appetite for large projects. I don’t think this one will overcome that reluctance.

John Homer is a professional engineer working in retirement as a consultant on construction projects. He lives near Indianapolis and can be reached at JohnHomerIN@gmail.com

This article originally appeared on Palm Springs Desert Sun: Engineer evaluates idea of pumping water from Mississippi to West

I note there were over 1000 comments when this post was delivered

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#43 2022-08-05 09:54:56

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 24,092

Re: Interstate 80 San Francisco Salt Lake City Water Pipeline

This is primarily for SpaceNut (all others welcome) ...

Because the Great Salt Lake pipeline would refill the Great Salt Lake (as well as provide sea water for other purposes in time) I decided to touch base with a resident of Salt Lake city. I asked for news of any local news items that might pertain to the pipeline.

The sheer scale of the project is highly likely to prevent serious consideration by anyone other than the Mars Society, which has even bigger problems to solve.

However, for folks like those who are members of or who associate with the Mars Society, a 700 mile pipeline that climbs to 8000 feet before dropping to 4000 feet is just a warmup exercise.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#44 2022-08-05 18:02:19

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,545

Re: Interstate 80 San Francisco Salt Lake City Water Pipeline

Pipeline materials will need to be concrete with a liner of fiberglass or other composite such as to resist scaling and corrosion of the pipe. Once it gets to the plant you most likely will have stainless and other metals within the system as sacrifice materials to slow corrosion.

The system takes in more sea water than what it delivers after desalination. Of course, the price is not just on the fresh water as the output of the higher concentration of the waste sea water will be considered hazmat.

If the wastewater processed fresh Water from the sewage treatment plant is used a dilutant then you could pass it into streams or rivers if the concentration of metals and other is low enough.

Offline

Like button can go here

#45 2022-08-06 16:57:11

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,545

Re: Interstate 80 San Francisco Salt Lake City Water Pipeline

Utah’s Great Salt Lake is disappearing

https://www.esa.int/Applications/Observ … sappearingSoon to be Utah's Salt Puddle or Salt Plains?

high concentration of nine toxic metals including arsenic.

Closing line may be similar to desalination of sea water as well.

Offline

Like button can go here

#46 2022-08-08 20:17:55

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,545

Re: Interstate 80 San Francisco Salt Lake City Water Pipeline

One of the issues for the draught has been that when rivers do not have the supply of water heading towards the ocean is that the ocean tides start to penetrate inland.

In dry California, salty water creeps into key waterways

Offline

Like button can go here

#47 2022-08-09 07:17:41

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 24,092

Re: Interstate 80 San Francisco Salt Lake City Water Pipeline

For SpaceNut re #46

Your post about salt water encroaching inland inspired me to think of Venice, Italy. Since the city is built (essentially) in the open sea, I wondered how the residents supply themselves with fresh water. Google came up with snippets that hint at the solution. They (apparently) collect rain water in "Venetian wells".

As mentioned, the only way for Venetians to have fresh water in Venice was by filtering rainwater and collecting it at the bottom of Venetian wells, which work differently from wells around the rest of the world.

Mar 1, 2022

Venetian Wells: The Idea That Made Life In Venice Possible

veneziaautentica.com › venetian-wells-venice

Google found this link for anyone who might wish to read more about Venetian "rain water" wells:

https://veneziaautentica.com/venetian-wells-venice/

The system lasted for centuries, but it depended upon government coordination and regulation.

the system was eventually replaced with an underground pipe to supply fresh water from a river some distance away.

However, the system of government coordination and regulation will surely become part of the Mars experience.

There will be NO free fresh water, or air for that matter. ** Every ** citizen will be sustained at a cost.

The traditional idea of "freedom" Americans like to imagine will have no place on Mars. The environment will force cooperation and common courtesy upon the citizens.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#48 2023-01-12 18:38:07

- SpaceNut

- Administrator

- From: New Hampshire

- Registered: 2004-07-22

- Posts: 30,545

Re: Interstate 80 San Francisco Salt Lake City Water Pipeline

Another topic for the Salton Sea but only in that we are talking about moving the ocean via pipeline to a different location for basically the same reason lack of water in them.

Offline

Like button can go here

#49 2023-01-20 12:46:24

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 24,092

Re: Interstate 80 San Francisco Salt Lake City Water Pipeline

https://www.yahoo.com/news/arizona-face … 49296.html

The article at the link above includes mention of a pipeline to fill the Great Salt Lake.

This is the first I've heard of it since the initial flurry of publicity.

Arizona Faces an Existential Dilemma: Import Water or End Its Housing Boom

Ciara Nugent

Fri, January 20, 2023 at 11:09 AM ESTArizona real estate Tuscon

The northeastern edge of the Tucson Mountains populated by two enormous subdivisions, Continental Ranch and Continental Reserve, part of Marana, Pima County, Arizona. Credit - Wild Horizon/Universal Images Group/Getty ImagesThis month, a suburb of Scottsdale, Ariz., found itself in the nightmare scenario for all communities living in the U.S.’ drought-stricken southwest: the water got shut off. Rio Verde, a master-planned community of some 600 homes, sprang up in the 1970s without its own piped water supply. For decades, it had relied on water trucked in from the city. But 20 years into a severe region-wide drought, Scottsdale says it must now conserve its water, which it gets from the Colorado River via a canal, for its own residents. Rio Verde residents are now skipping showers and driving miles in search of drinking water. On Jan. 12, the community filed a high-profile lawsuit against Scottsdale.

The drama in Rio Verde encapsulates, in miniature, an existential question facing the whole of Arizona: in an era where climate change is shrinking the water supply, should the desert state keep building homes that depend on water from elsewhere?

The answer, given Rio Verde’s current plight, may seem obvious. But that is precisely the question that authorities and developers in Arizona are mulling as they look to sustain one of the nation’s biggest population booms. Since 2000, as the Colorado River has dried up, Arizona has become increasingly reliant on pumping groundwater, which today provides 41% of the state’s needs. Meanwhile some cities, like Tucson, have gone to great lengths to cut back on the amount of water used per resident. Yet at the same time, Arizona is enthusiastically welcoming tens of thousands of new residents—lured by cheap housing and endless sunshine—each year. In 2022, four of the ten fastest-growing counties in the U.S. were in Arizona, according to census data, with Maricopa County, where Rio Verde is located, at number eight on the list. (As well as families, other thirsty new arrivals to the state include tech companies, whose data centers require millions of gallons of water to keep servers from overheating.)

The Colorado River is seen receding at the Glen Canyon Dam on October 23, 2022 in Page, Arizona.Joshua Lott—The Washington Post/Getty Images

The boom can no longer survive on groundwater. On Jan. 9, Arizona’s new Democratic governor Katie Hobbs released a report, withheld from the public by her predecessor Republican Gov. Doug Ducey, which shows that a large area west of the White Tank Mountains, to the west of Phoenix, hasn’t got enough groundwater to sustain all the homes—enough for 800,000 people—that developers want to build there. To get approval, Arizona’s Water Resources director told local media, major projects will need to “find other water supplies or other solutions.”

With the state’s river water already spoken for, those “other” supplies, experts say, would likely mean imported water. Pie-in-the-sky projects to bring in water from outside Arizona, such as a 1,000 mile pipeline from the Mississippi River, have bounced around the state legislature for years. As climate change deepens the state’s water crisis, though, one drastic idea has gained traction. In December, Arizona’s newly expanded state water finance board voted to advance a proposed $5 billion desalination plant in Mexico’s Sea of Cortez—potentially the world’s largest—which would pump water north via a 200 mile pipeline. IDE, the Israeli company behind the proposal, says it is now submitting for federal environmental review.

Bring the water

Moving water from water-rich areas to dry ones is nothing new. Canal systems that did just that were crucial to the U.S.’ westward expansion in the 1800s. In Arizona, more than 80% of the population relies on a man-made channel that diverts water from the Colorado River on the state’s western edge to population centers further east. But today, intensifying droughts and population explosions are pushing southwestern leaders to consider huge projects that would bring water from ever further away. In Utah, where migration is driving never-before-seen growth, a legislative committee has floated the idea of building a pipeline from the Pacific Ocean to refill the parched Great Salt Lake. Nevada, which has been growing rapidly for half a century, regularly discusses similar ideas.

Home builders and agribusiness groups see in such proposals the promise of an infinite, “drought-proof” water supply that could sustain the southwest’s growth for decades to come. But critics see a different future, one where imported water fuels environmental destruction and soaring utility prices for consumers, and where U.S. states become dependent on good relations with a foreign country for their survival.

Margaret Wilder, a human and environmental geography professor at the University of Arizona’s School of Geography, Development & Environment, warns that large-scale desalination projects could be used by the real estate industry to justify “much more unsustainable development in the desert in future.”

The prospect of slowing Arizona’s population growth “is the 800 pound gorilla in the room that no water authority wants to talk about, because it’s politically untenable to do so,” Wilder says. As a result, she adds, “desalination is being presented as an inevitable fate for Arizona.”

Importing problems

Environmentalists say the IDE desalination project would harm the planet on several fronts. First, where the water is desalinated on the Mexican coast, the waste salt would likely need to be deposited back into the Sea of Cortez, threatening an area so rich in wildlife that Jacques Cousteau called it “the world’s aquarium.” Second, the project’s pipeline would cut through land home to Mexican people and wildlife, and, on the Arizona side of the border, the Organ Pipe National Monument. Third, the desalination process is hugely energy intensive, and its large-scale use can generate significant greenhouse gas emissions—which are the source of the climactic changes limiting the region’s water supply in the first place.

John Hornewer sets alarms on his phone in two minute intervals, after which he puts a quarter in the fill station, as he fills up his 6000 gallon tanker to haul water from Apache Junction to Rio Verde Foothills, Arizona, U.S. on January 7, 2023.<span class="copyright">The Washington Post/Getty Images</span>

John Hornewer sets alarms on his phone in two minute intervals, after which he puts a quarter in the fill station, as he fills up his 6000 gallon tanker to haul water from Apache Junction to Rio Verde Foothills, Arizona, U.S. on January 7, 2023.The Washington Post/Getty Images

“We as Arizonans can’t just keep taking water from somewhere else without considering how it impacts the people and places we’re taking it from,” says Cary Meiser, conservation chairman of the Yuma Audubon Society and coordinator of the Sierra Club’s Colorado River Task Force.

Even ignoring those environmental risks, the cost for Arizona residents could be great. At the moment, cities in the state typically pay about $50–$150 for one acre-foot of water—or 326,000 gallons, enough to cover an acre of land in a foot of water. That’s roughly the amount used each year by an average family of three in Phoenix, according to the state’s director of water resources. IDE’s director estimates their desalinated water would cost roughly $2,200 to $3,300 per acre foot. The final price for consumers would be determined, and possibly subsidized, by local governments. But it could become unaffordable for low-income families to live in parts of the state that are reliant on imported water.

A dry path ahead

That cost problem means that, even if desalination provides a bountiful supply of water for Arizona, it likely won’t save the state’s real estate market, says Jesse Keenan, associate professor of sustainable real estate at Tulane University. The industry’s recent success, he says, relies on “a fiction of limitless cheap housing,” sustained by the government’s ability to provide water cheaply. If that can no longer be done everywhere, the cost of properties with stable water connections will spike. And, since people who have to spend more on utility bills have less to spend on mortgage bills, banks may stop lending on homes in regions reliant on expensive imported water. “We’ve reached the limit of the public sector’s capacity to conquer nature with infrastructure,” Keenan says. “Now’s the moment where the private sector will bring discipline.”

Environmentalists are advocating discipline in Arizona’s relationship with water, too. They want the government to focus on cutting water demand rather than expanding supply. That would mean measures to control or limit real estate development, as well as encouraging further water-saving measures by existing consumers, pushing farms to swap out water-intensive crops like alfalfa, and better regulating groundwater use.

Hobbs’s governorship may mark a turning point. She has promised to create a council to oversee the modernization of groundwater rules, and their implementation. Her office says the body will also seek to close loopholes that have allowed developers to skirt a 1980 law requiring proof of a 100-year water supply for projects with more than six homes. (Rio Verde’s developer, for example, parceled its homes into groups of five or less.)

The governor will face pushback from the Republican-led state legislature, which has repeatedly rejected proposals involving stringent limits on groundwater use in rural areas.

But as more water disputes like Rio Verde’s crop up, Wilder is hopeful that Arizonans will understand the risks of never-ending expansion into the desert. “I’m not an advocate of pulling up the bridge behind us, but we need to slow this train down,” she says. “We need to start asking questions when people present us with these unproblematic, carefree solutions to the water problem.”

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here

#50 2023-02-05 11:13:29

- tahanson43206

- Moderator

- Registered: 2018-04-27

- Posts: 24,092

Re: Interstate 80 San Francisco Salt Lake City Water Pipeline

https://www.yahoo.com/news/opinion-grea … 17216.html

The article at the link above does not mention a pipeline from California.

LA Times

Opinion: The Great Salt Lake is disappearing. Utah has 45 days to save it

Stephen Trimble

Sat, February 4, 2023 at 6:00 AM EST

A couple walks along the receding edge of the water after record low water levels are seen at the Great Salt Lake Tuesday, Sept. 6, 2022, near Salt Lake City. A blistering heat wave is breaking records in Utah, where temperatures hit 105 degrees Fahrenheit (40.5 degrees Celsius) on Tuesday, making it the hottest September day recorded going back to 1874. (AP Photo/Rick Bowmer)

The receding shoreline of the Great Salt Lake in September 2022, two months before it reached its historic low level. (Rick Bowmer / Associated Press)

We often describe the stillness and quiet of the desert as timeless. But deserts are dynamic and desert lakes fragile, none more so than Utah’s Great Salt Lake.Emblematic of the West’s Great Basin, the Great Salt Lake has no outlet. The lake can only hold its own against evaporation if sufficient water arrives from three river systems fed by mountain snowmelt. When inflow decreases, the lake recedes. Each year since 2020, the Great Salt Lake received less than a third of its average (since 1850) stream flow. The lake level fell to the lowest surface elevation ever recorded, 4,188 feet above sea level, in November 2022.

The crisis is real. The Great Salt Lake is disappearing.

This largest saltwater lake in the Western Hemisphere is essentially a shallow saucer, with an average depth of just under 15 feet. Every one-foot drop in surface level matters. By the end of last year, the lake had lost 73% of its water and 60% of its area, exposing more than 800 square miles of lakebed sediments dense with heavy metals and organic pollutants.

A group of 31 concerned scientists and conservationists issued a call to arms on Jan. 4. Without emergency action to double the lake’s inflow, it could be gone in five years.

Settlers in Utah who have lived with the Great Salt Lake for 170 years have mostly taken the iconic “briny shallow” and its fiery sunsets for granted, a given in the state’s landscape and resources. The lake and its wetlands yield minerals, thousands of jobs, and an annual $2.5 billion for the Utah economy. Its brine shrimp eggs are used worldwide as food for farmed fish and shrimp, providing crucial calories for millions of people. The lake suppresses windblown toxic dust, boosts precipitation of incoming storms through the “lake effect,” and supports 80% of Utah’s wetlands — critical habitat for globally significant populations of migratory birds.

All these wonders do best with a minimum healthy surface elevation of about 4,200 feet, which the Great Salt Lake hasn’t seen for 20 years. And while this winter’s atmospheric rivers brought record precipitation that raised the lake by a foot, water diversions have continued unabated. A drying and warming climate will increase evapotranspiration and decrease stream flow, but it is irrigated agriculture that has created our current crisis.

As the lake shrinks, it grows saltier, now measuring 19% salinity (six times as salty as the ocean), well past the 12% salinity favored by two crucial food chains in the lake. Algae feed the brine shrimp; mats of cyanobacteria growing on mounds called microbialites nourish brine flies. More than 10 million migratory birds, in turn, feast on these shrimp and flies.

Each of the migrating 5 million eared grebes that return to the lake each year eats 30,000 brine shrimp a day — for months. Half of the world’s population of Wilson’s phalaropes depends on the lake’s brine flies and midge larvae to take on fat reserves for their 3,400-mile nonstop migration to South America. Without the lifeline of the lake and its resources, these birds can’t survive their migration.

The shrimp and flies haven’t disappeared yet, but the retreating lake has beached the microbialite mounds “like tombstones,” in Bonnie Baxter’s words. That spells famine for the phalaropes. In the summer of 2022, Baxter, director of the Great Salt Lake Institute at Salt Lake City’s Westminster College, encountered no adult brine flies and no birds on the shores of the lake’s Antelope Island, now a peninsula because of low water levels. She should have seen hovering clouds of the insects. “We’re seeing this system crash before our eyes,” Baxter says, with sorrow.

A total collapse in food-chain resources could lead to Endangered Species Act listing for any of these species at risk. Such a listing would have an immeasurable impact on water management in northern Utah, with federal intervention in every proposed project that might affect stream flows and aquifer recharge.

These facts have caught the attention of Washington and Utah politicians.

President Biden signed the Saline Lake Ecosystems act in December, providing $25 million to study and monitor vulnerable salt lakes across the Intermountain West. Such funding is welcome, but the lake needs water, not studies — about 2 million acre-feet arriving each year.

Because Utah manages its own water, it is finally up to the state Legislature to save the lake. We can’t legislate weather or climate. But we can pass mandates and incentives to reduce water use, especially by agriculture, which accounts for two-thirds of diversions in the Great Salt Lake watershed.

Nearly 70% of water used by Utah farmers goes to raising alfalfa hay — a water-intensive crop that adds just 0.2% to the state’s gross domestic product. Nearly all that water is unmetered; farmers have no financial incentive to conserve. As for household consumption, Utahns use the most domestic water per capita in the Southwest and pay the least for their water of any state.

Some legislators dream of fixes that won’t involve cutbacks: tree-thinning in mountain forest that might increase runoff, cloud-seeding, pipelines. None of these will suffice, according to water experts.

Significant legislation and creative funding ideas are coming from both Democrats and Republicans. One proposal would divert sales tax money to compensate ranchers and farmers who let fields go fallow. A proposed Great Salt Lake Authority would centralize management. Grants for high-tech “agriculture optimization” could decrease farmers’ water use by 30%. Modernizing water rights law could keep water in streams and deliver more inflow to the lake.

The Utah Legislature began its 2023 session on Jan. 17. Its members have 45 days until the end of the session on March 3 to take action to save the Great Salt Lake from collapse. Scientists say waiting another year will be too late for the lake to recover. Brigham Young University ecologist Ben Abbott, lead author of the scientists’ call to arms, sums up the challenge: “We’ve got to act now. Unlike politicians, hydrology doesn’t negotiate.”

Record snowfall blanketed the Wasatch Mountains above Salt Lake City this winter. But a single year’s anomalous change in weather can’t alter one stark fact: Utah is — and will remain — the second-driest state in the nation.

Utah must come to grips with its arid heart.

Stephen Trimble lives in Salt Lake City. A 35th anniversary update of his book "The Sagebrush Ocean: A Natural History of the Great Basin" will be published next year.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.

(th)

Offline

Like button can go here